Titane (Julie Ducournau, France/Belgium)

By Phil Coldiron

The erotic history of the car in cinema extends back nearly to the dawn of the medium: there’s Chaplin, in 1914, asserting in his first film that he’s a more enticing view than the soapbox derbies at the Kid Auto Races (no engines yet). Though the death-drive desires Chaplin glimpsed would go on being worked out by Lloyd and Keaton up through Crash (1996) and Death Proof (2007), the human-car relationship has generally been more accommodating, less overt in its violence. The car is context, an acutely American site for allowing public and private to mingle in little eddies of erotic energy, a dynamic whose extratextual apotheosis is the mirror-stage kitsch of the mid-century drive-in. The savour of that context, unsurprisingly given the volume of examples, varies wildly. And of course, countless examples abound where it’s just a spot to cuddle, to kiss, to fuck, because that’s what one does in a car culture.

The car also frequently functions as a sign of desire or a metonym for what can’t be shown, yet there’s a still rarer type: the film in which the car itself is, quite literally, a sexual object. Though I can’t say for certain where this lineage begins, Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965) is one possible genesis; an astonishing volume of amateur productions make up the bulk of its corpus; and Julia Ducournau’s Titane, freshly minted with a Palme, is its latest and most pedigreed instance.

But I’m going too fast. While it’s true that, as you’ve surely heard, Titane is the movie where a woman fucks a car—two, actually: a flame-decaled vintage Cadillac and a contemporary fire truck—these moments play out with a weird, entranced automatism that scrambles any of the usual routes for making sense of desire. Put more bluntly, while the facts onscreen inescapably place Ducournau’s film in this odd little genre, the matter of how exactly these machines serve as sexual objects for our heroine is ambiguous in a way which is typical of the mechanics of the film at every level. Ambiguity is one of the signal clichés of contemporary midcult art: as both an aesthetic and discursive strategy, it’s perfectly neutral, like all clichés. What I’m interested in are the ways in which Ducournau makes use of this cliché and others.

Though one of the trade hacks on the Croisette felt moved to describe Titane’s story as unprecedented, the clichés begin with its narrative model, which renovates the Vertigo (1958) plot. There’s a marked tension between Ducournau-the-writer, whose script is gratifyingly lean, and Ducournau-the-director, with her fondness for grand pile-ups of meaning and sensation. The bones of the story can be easily summarized. A young girl, Alexia, suffers a traumatic accident; now an adult (Agathe Rousselle), she re-enacts that trauma in both her professional and personal life, before seeking to resolve it through a series of increasingly spectacular violent acts; and, having done so—though the success of her attempt is nowhere near certain—she tries to first escape punishment and then to find her place in a new life by moulding herself physically, and allowing herself to be moulded, into the image expected of her.

This image belongs to a long-missing young man, the son of Vincent (Vincent Lindon), an aging fire chief who, in one of the film’s many rhymes and doublings, destroys himself daily with chemicals in a desperate attempt to ward off time and go on fitting the hypermacho physical image expected of him. That Alexia is attempting to reconstitute herself in the image of this sad man’s son while pregnant herself with a child sired by the aforementioned Cadillac should give something of an idea of the fluid and messy conception of sex and gender which hums throughout Titane. This odd and at times moving folie à deux of image relation finally gives way to a glib and chic transhumanism, as Titane literalizes Donna Haraway’s cyborg just as Ducournau’s Grave (2016) literalized Tiqqun’s Young-Girl. Glib and chic not because Alexia’s automotive desires remain on the far side of ambiguity throughout—it’s plainly mythological, and one doesn’t question the techno-gods—but because this mythological dimension, swerving between pagan and Catholic, amounts in the end to viral-ready decoration grafted onto a more conventionally compelling melodrama of belief. It’s not lost on me that mythology and virality present their own problems of belief, and that decoration and irresolution present their own problems of convention or taste. What’s less clear to me is the degree to which a film as exquisitely engineered as Titane can ever be as troubling as the pose of transgression it strikes.

Here I’ll admit something old-fashioned: I think it still matters that art is memorable. Transgression, the shock of the new, is one of cinema’s most well-worn routes to this. That such an approach, which often depends on a single image being strange enough, or violent enough, to impress itself on each viewer’s memory while standing for the whole of a film, has led directly into the miserable convention of One Perfect Shot only confirms the saintly equanimity of our algorithms in their quest for frictionless circulation. Titane, of course, enters that world of algorithmic circulation: what’s shocking is liquidated as soon as possible. And yes, fucking a car remains outré enough to register as “shocking,” at least in the context of the kind of art film which receives wide distribution.

But it may be that I’m making overwrought excuses for the simple fact that I find Ducournau’s staging of these woman-on-car moments to be bland: the first alternates between Rousselle writhing in the car’s backseat and a long shot of its hydraulic bounce, while the second is shown in a single long shot framing Rousselle in the truck’s front window, which clarifies certain previously murky logistics. The impossibility of untangling this response, which I feel as aesthetic, from my knowledge of the discourse machine awaiting this film—the way in which it’s impossible for me to see these images without feeling Ducournau’s own awareness of what awaits—is the little mechanical baby that now lives inside each of us.

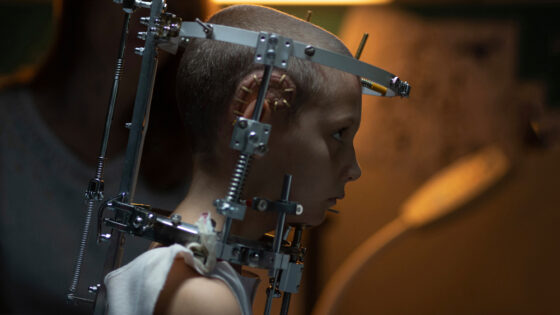

And what of the film’s little mechanical baby? It’s here, in pregnancy rather than sex, that Ducournau produces images which stick sharply in the mind, as the film’s disjunct registers finally fuse together. To return to clichés of ambiguity: Alexia is both Mary and Jesus, both the bearer of an immaculate conception and the holy sacrifice which brings something new into the world. (Vincent, introducing her to the firehouse hunks as his returned Adrien, reminds them, “I’m your God, and this is my son.”) She mortifies the flesh anew each day, tightly bandaging herself, leaving her torso covered in welts and scars which jar against the gonzo images of her body—vagina, nipples, a conspicuously placed abdominal wound—leaking motor oil, giving her passion a marked ecological dimension. Vincent needs to believe that this is his son; it’s unclear what Alexia needs to believe, or if she believes anything at all. Rousselle’s almost entirely silent performance, particularly once her head is shorn (echoing Falconetti and Claude Cahun, among others) and she’s draped in a too-large fireman’s suit, insists that it means nothing beyond its surface.

This is both form and content: masculinity—as surface, as image—is terrible and ridiculous, but when it finds its way into the right hands at the right moment, not beyond redemption. Ducournau, with her typically heavy hand and taste for the biblical, gives shape to this idea time and again in her most memorable images, nearly all of which are built of a darkness failing to keep out narrow bands of dense, sculptural light. This darkness, grey verging into black, articulates the film’s own abundance of potential meaning, an abundance of which its engagement with sex and gender is only a single strand. (I’ve not touched on at least another dozen of its self-consciously serious themes and motifs.) Ducournau is not naïve: nothing in Titane leads me to believe she is unaware of the ease with which her film will click into its place in the discourse machine. Whether the proper functioning of that machine is a source of pleasure remains a question each viewer must answer.

Phil Coldiron- « Previous

- 1

- 2