Global Discoveries on DVD: Now or Never

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

In what will likely be my last column in these pages, I’ve mainly tried to highlight releases and films that I’ve been meaning yet failing to watch for ages, following the assumption that it’s now or never. As most of my examples make clear, this avoidance has something to do with the unhealthiness or pessimism these films tend to leak from every pore.

But before getting around to these overdue discoveries, I’d like to celebrate a couple of “late” arrivals that are just over a century old. Frank Borzage’s Back Pay and what survives (about 50 minutes’ worth) of The Valley of Silent Men, both 1922 features made for William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Productions, had to wait 101 years to wend their way towards us, at least for the purposes of this column. The former is a three-hanky sob story adapted by Frances Marion from Fanny Hurst; the latter is an action-adventure filmed in Canada. They’re jointly available on both DVD and Blu-ray from Undercrank Productions.

By recently collecting some of my literary and jazz criticism along with some of my film criticism, as related activities and interests that can serve and clarify one another, I’ve sought to avoid the routine capitalist censorship that forbids this practice as an egregious form of “cross-marketing” and insists on keeping these arts separate; and this in turn has guided some of my viewing habits. One of my keenest pleasures in watching Back Pay relates to Borzage only tangentially: rather, it comes from feeling cinematographer Chester Lyons’ exquisitely tinted and toned landscape shots alternate with scene-setting intertitles decorated with illustrations of the same scenes and settings. The graceful transitions between these complementary, yet distinctly different, renditions of the same visual subjects are, paradoxically, very literary—even though the images sometimes matter more than the words, because they correspond to the ways we can imagine separate visual settings for the narratives while we’re reading or hearing them read. Two-part inventions of sound and image that play catch with one another, they’re clearly invested in the same storytelling game. This orchestrated polyphonic flow takes on an even richer texture in talkies, e.g., the smooth, bumpless relays and exchanges between spoken narration, music, and onscreen dialogue in the very literary openings of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons and Leopoldo Torre Nilsson’s La casa del Angel (1957), with its similar percussive, Wellesian cadences.

Harvé Dumont reports in his superb critical biography of Borzage that, according to Chaplin biographer David Robinson, Back Pay influenced Chaplin’s 1923 A Woman in Paris. (Maybe it did, but Robinson excluded this fact from his own biography.) We’re accustomed to regarding ourselves as being more sophisticated moviegoers than our equivalents one century ago, yet this movie periodically suggests that our ancestors might have been aesthetically and ethically freer than us. A Wall Street sugar daddy can be appreciated for his generosity alongside his more guilt-ridden and self-centred mistress—the latter played by Seena Owen, who also plays the queen who chases Gloria Swanson out of her palace with a whip in Stroheim’s last silent feature, Queen Kelly (1929).

Owen’s character here is a restless heroine who leaves her small town and her dopey but loyal boyfriend for New York luxury, which she attains only by becoming a banker’s kept woman. Her life becomes much more melodramatically Hurstian after her dopey and loyal small-town boyfriend loses his eyesight, the use of one lung, and his life, in that order, fighting in World War I (still a recent memory in 1922), bringing on enough wallowing survivor’s guilt to rival that of the mulatto daughter in Hurst’s Imitation of Life.

***

Ozu Yasujiro’s Record of a Tenement Gentleman (1947)—the first of his postwar features—is included in BFI Video’s double Blu-ray set Three by Yasujiro Ozu, along with his silent Dragnet Girl (1933) and A Hen in the Wind (1948), the second of his postwar features. It’s also one of the few surviving Ozu films that I hadn’t already seen. (Full disclosure: My essay on A Hen in the Wind is included in this set’s 30-page booklet.)

I can’t fathom why the BFI—or, more precisely, someone at the BFI—has chosen to package Ozu’s first two postwar films with one of his unrelated silents (unless this was prompted by the thematic persistence of poverty), but I’m delighted to report that my long-term clamouring for an English translation of Hasumi Shigehiko’s Directed by Yasujiro Ozu has finally been gratified by Ryan Cook and University of California Press, with a March 12 publication date. A critical study that frees us in the West from the manufactured exoticism that has encrusted and distorted our appreciations of Ozu, the book helps us to recognize and appreciate some of the more authentic mysteries that remain.

Hasumi’s book alerts us, for instance, to the fact that Ozu’s preoccupation with seasons in his film’s titles can’t be found anywhere in the films themselves. This alerts me to the more general inscrutability of Ozu’s other film titles, whether they seem to refer to obscure and unidentified Japanese expressions (as in I Was Born, But… [1932] and A Hen in the Wind) or are the vaguest of referents to what the films are about (as in Passing Fancy [1933] or Tokyo Story [1953]). This is even more true of Record of a Tenement Gentleman, a film about a grumpy aging widow and the little boy, an apparent war orphan, whom she reluctantly adopts—not about any tenement or any gentleman, much less any tenement gentleman, as Tony Rayns points out in the booklet. I’m tempted to conclude that this arbitrary contrariness may come closer to comprising the Zen flavour of Ozu’s oeuvre than anything else.

***

A lonely night watchman at a department store develops a fixation on one of the store’s female mannequins. He steals it/her and brings it/her home, where he can be with her/it all the time. One reason why it’s important to describe Arne Mattsson’s Swedish film Vaxdockan (The Doll, 1962)—released one year after L’année dernière à Marienbad and 11 years after Mattsson’s One Summer of Happiness (available now from moviedetective.net and myrarefilms.co.uk)—by insisting on these alternate pronouns is that the film keeps switching without warning between a mannequin and a live woman, thus alternately shattering and revalidating the watchman’s fantasy.

My reason for avoiding this film for so long clearly had something to do with my wariness about approaching a sicko fantasy, but the dual identity suggests that I might have been wrong about this. Rightly or wrongly, I connect the film’s ethical challenges (whereby a “real-life” fornicating couple in the story are made to seem far more repellent than the innocent and tender watchman) and its perceptual challenges (dummy or lady?) with the fact that both a man and a woman (Lars Forssell and Eva Seeberg) are credited with the screenplay.

***

If style is the miscarriage of form (as I believe Roland Barthes suggests somewhere), stylishness is surely the miscarriage of style, as exemplified by Joseph McGrath’s joyless, if very stylish, The Bliss of Mrs. Blossom (1968). I enjoyed this 55 years ago for its riotously loud colours and for Shirley MacLaine, but it’s surely significant that these are the only elements I could remember afterwards. Watching it recently on a Kino Lorber Studio Classics Blu-ray, I had to deal with its humourless substance as a very mechanical farce about adultery, which it pretends to celebrate. Now, its unfelt stylishness makes it far less durable or watchable than Frank Tashlin’s un-chic yet joyful Artists and Models (1955), which also boasts riotously loud colours and Shirley MacLaine, but makes them both part of its comic-book style rather than parts of its window dressing.

***

As a teenager in the 1950s, I tended to avoid Hugo Haas/Cleo Laine quickies after catching a few whiffs of their sub-noirish morbidity, but this is precisely what animated my recent curiosity to explore some of them on YouTube. Many can still be accessed on DVD and/or Blu-ray, but a far more appropriate venue would be to catch sneak peeks of them online and then hopefully forget them, as one does or tries to do with unpleasant dreams. At least that’s what I attempted to do with Bait (1954) and Hold Back Tomorrow (1955), two separate versions of the same perverse romantic triangle in which Haas, as clumsy writer and low-budget director, drafts Laine and John Agar—who plays both the handsome romantic lead in the former and the ugly/nasty bully that the filmmaker usually plays himself in the latter (a strangler of women awaiting his execution and/or redemption, whichever comes first).

The usual backdrop of metaphysical doom is apparently what got Haas to hire Sir Cedric Hardwicke to play the Devil as an autograph-signing celebrity in the weirdly self-referential prologue to Bait, which more equitably co-stars Laine, Agar, and Haas (the latter playing a crazed gold prospector bent on messing up or murdering the other two). What prevented me from forgetting these grim camp mixtures of Dostoevsky and Edgar G. Ulmer was looking up Haas on Wikipedia, where I discovered he was a Czech Jew who lost his father and brother to the Nazi death camps as well as his respectable careers as a musician, stage actor, and filmmaker before emigrating to the American Poverty Row in 1940—all of which seemed to inform his nightmarish plots with heaps of survivor guilt and related forms of remorse and self-hatred.

***

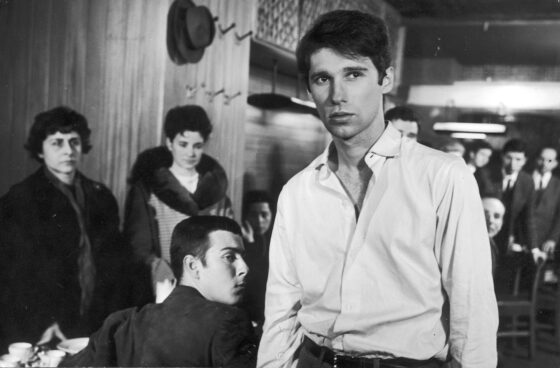

For some time now, diverse Portuguese friends, hosts, and acquaintances have been urging me to watch films by Paulo Rocha (1935-2012), half a dozen of which have recently been restored for the Portuguesa Cinemateca on three no-frills DVD box sets. These represent only a fraction of Rocha’s total output (and don’t even include his documentary about Manoel de Oliveira’s first film), but the two that I’ve seen so far, A Ilha dos Amores (Loves’ Island, 1982) and A Ilha de Moraes (Moraes’ Island, 1984), are so impressive that they’ve whetted my appetite for more. (The two I plan to watch next are Pedro Costa’s favourites, Os Verdes Anos [The Green Years, 1963] and Mudar de Vida [Change of Life, 1966]; both are also available from Grasshopper Films, and Costa supervised their restorations.)

I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that my former reluctance to dip into Rocha’s work partially stemmed from a fear that readers might mix him up with Paulo Branco, Glauber Rocha, or any or all of the five other individuals called Paulo Rocha listed on Wikipedia (an actor, politicians from Brazil and Cape Verde, and Portuguese and Brazilian football players). Or maybe it was an unconscious Yank desire to preserve my innocence about both colonial/anti-colonial cinema and Latin America in general and their Portuguese branches in particular, thus banishing them to the fringes of our awareness.

Both Loves’ Island and Moraes’ Island—respectively, a fictionalized biopic and an exploratory documentary—are about the Portuguese poet Wenceslau de Moraes (1854-1929), a naval officer in Mozambique and Macao who quit the service to head Portugal’s first Japanese consulate in Kobe and Osaka. While in Japan, he converted to Buddhism and married a former geisha named Fukumoto Yone; when the latter died in 1912, Morae was so grief-stricken that he severed all his professional ties and moved to Yone’s hometown, where he lived with her niece and visited her grave every day. After the niece died, he visited the graves of both women daily until his death.

In Moraes’ Island, Rocha’s dialogues with people who encountered Morae aren’t interviews but rather relaxed conversations, devoid of showboating and self-consciousness. Not exactly journalistic, they are acts (not performances) of religious piety and cult-like devotion, but it’s never entirely clear what the piety and devotion are for: Morae’s poetry, his exile and loneliness, or his capacity to straddle three cultures (Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese) while living with death—expressing even a devotion to death that recalls that of Truffaut’s character in La chambre verte (1978), which is set in what appears to be roughly the same period.

As I’ve argued previously in this column, criticism and fandom are often activities in conflict, yet I think it can be argued that this film intermittently succeeds at combining them whenever it objectifies its own obsession with Morae. Am I suggesting that Rocha’s formal shaping of the materials allows us to stand outside this subject while recognizing its manifestations in our own reflexes, regardless of whether we’re colonialists or anti-colonialists or (most likely) both? Yes.

Jonathan Rosenbaum