Eight Footnotes on a Brief Description of Footnotes to a House of Love, and Other Films by Laida Lertxundi

By Phil Coldiron

…A group of young people1 in the California2 desert.3 A radio.4 A house that’s little more than the idea of a house.5 A woman6 crosses a room, passes by the camera,7 says, “You’re leaving me…”8

1. What does it mean to make youth cinema in America today? While Hollywood aged parabolically from birth through the maturity of the studios back to the eternal adolescence of the focus group, independent cinema continually positions itself precariously at the boundary between youth and maturity. Today we see it as much in the online dispatches of the 99%—televisual recordings that are simultaneously an affirmation of self and the edification of history—as in the cinema proper, whether narrative or otherwise. Though youth cinema is by no means restricted to the biologically young, the ability to figure this tension from inside the experience of living it sets apart (as it always has) the best young filmmakers working in America today, directors as disparate as Harmony Korine, Michael Robinson, Matt Porterfield, and Alex Ross Perry. This is the group to which Laida Lertxundi belongs.

Young bodies populate Lertxundi’s four major films to date. In Footnotes to a House of Love (2007), seven young men and women circulate in and around a crumbling cabin in the desert, sprawling in miniature in a utopian vision of love and creative destruction. My Tears Are Dry (2009) reduces the scope to two alternating shots of partially viewed women in domestic spaces. The teens of Cry When It Happens (2010) lounge in apartments and motel rooms. The second section of the triptych A Lax Riddle Unit (2011) explores the apartment of a young woman who appears briefly, playing along with Robert Wyatt’s “Alifib” on a keyboard and flopping on a bed. Lertxundi, whose framings are both loose and precise, offers these bodies piece by piece, discarding individuality for the collective presence of youth. The editing that brings these pieces together is very basic, placing shots crudely beside one another. As youth extends into the montage, the tentativeness of the amateur turns out to be the simple certainty of the master.

2. Born in Bilbao, Lertxundi continues a rich tradition of European directors engaging with Los Angeles, though unlike her most famous forbearers—Antonioni, Demy, Varda—one senses that for her Los Angeles is very much home (it comes as little surprise that she was a student of Thom Andersen at CalArts). Her Los Angeles is one of quiet apartments, empty alleys and parking lots, skies that can still be blue rather than the opaque orange of smog (though she makes excellent use of this uniquely Angelino hue in the closing section of A Lax Riddle Unit). This is a vision of the city that languidly, powerfully asserts the existence of a social space beyond Hollywood. Though her films are in no way overtly political, they become so when considered against the Deleuzian conception of Hollywood as a place that responds to its own lack of history by creating stories it forces the entire world to believe: they are the creation of a history that will one day allow Los Angeles to rid itself of Hollywood, a far more productive path than satirizing a system capable of incorporating all critiques into its own perpetuation.

3. The second key aspect of Lertxundi’s Los Angeles is its basis in landscape: all four films make relatively extensive use of a natural world beyond the strip malls and highways that are its most common cultural markers. Though Lertxundi’s images of these spaces are not without precedent—Gary Beydler’s Hand Held Day (1975) in particular, but also Zabriskie Point (1970) or the landscape work of James Benning (another CalArts connection)—her conception of them is unique, insofar as they exist in a harmonious continuity with her interior spaces. The house and the desert in Footnotes exist as a single entity, creating a dialectic not of inside and outside, but of presence and absence in a unified space: the first instance of that dialectic which is the basis for each of her films.

My Tears Are Dry, working with only three camera set-ups—two interior, one exterior—plus a black frame, extends Lertxundi’s conception of the presence-absence dialectic beyond the image into the whole of the film. The film begins by alternating between two static shots: the torso of a woman laying supine on a bed with a tape player clutched to her stomach, on which she plays the opening bar of Hoagy Lands’ song of the same title before stopping it abruptly; the back of a woman seated on a couch idly plucking out notes on a guitar. After six alterations the film settles on the reclining woman, Lands’ song begins to play in full, and a ragged pan up the woman’s body leads to a cut from inside to out, framing an empty alley. In the alley space the camera slowly tilts up, settling on an image of the sky intruded upon by a single palm tree. The image cuts abruptly once again, this time to a black frame as “My Tears Are Dry” plays to completion. The movement in Tears is from false—the illusion of a continuous, unified interior space via cross-cutting; the artificially constructed contiguity of interior and exterior—to true: the fluid contact of social (the alley) and natural (the sky) leading to the reification of the absence sublimated in the cross-cutting in the form of the black frame. Taken as a whole, we can see the movement from false presence to true absence—My Tears Are Dry, with its frank depiction of this natural longing, is one of the only genuinely sad films ever made.

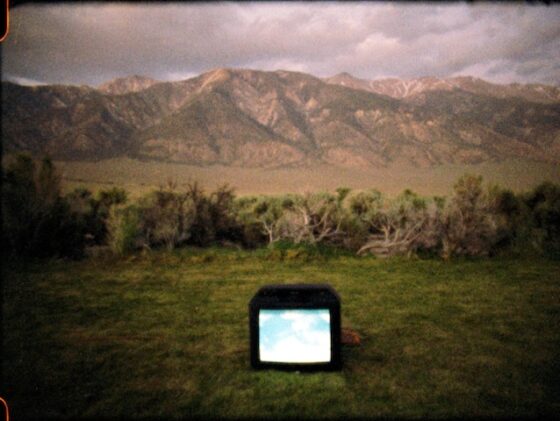

Both Cry When It Happens and A Lax Riddle Unit push this presence-absence dialectic into new territory, the former expanding Lertxundi’s conceptual scope and the latter finding new contexts. Cry inverts the trajectory of Tears by moving from images of true presence (two girls embracing on a couch, two boys lounging in a motel room) to an image of false absence in the form of Lertxundi’s only symbol to date. This symbol, the central image of the film, is a frame of blue sky that circulates through both a television screen in various locations within the image and the full 16mm frame itself; here the fluid movement between the social and the natural seen in Tears is reduced to a single, fixed image, simultaneously condensing and exploding the prior relationship. In its “direct” 16mm presentation, the image alternates with a frame of a motel office, Los Angeles’ City Hall prominently reflected in one of its windows. In the “contained” TV presentation it moves from an apartment where it is wheeled about, to the motel room of the boys (where it is first linked with The Blue Rondos’ “Little Baby,” heard playing softly as if from a neighbouring room, and which accompanies every “direct” occurrence of the image afterward), and finally to nightfall in front of a possibly artificial desert vista. The TV sky, alone in the black of night, eventually blinks out, leaving only “Little Baby,” a wash of white noise and the set’s blinking on-off light in another black frame—no longer the restored image of absence effaced, but the third order of Lertxundi’s reflexive inquiry into the mediation of nature by the social: there is the direct image, the image of the image, and in the end, only the memory of the image, triggered by the mediator that has outlasted it (nature itself is the zero degree). Against the longing—a term dependent on a past or future—discovered at the heart of My Tears Are Dry, here Lertxundi has found a radical confirmation of the present tense: the pleasure or sadness of lying around with someone you love, of looking out from cliffs onto the ocean, of sitting in a cheap motel, are all a part of the unified whole of the natural world, the point of origin from which eternal memories spring. The future tense title is only a reminder.

A Lax Riddle Unit shifts Lertxundi’s focus from the personal to the communal. Comprised of three distinct sections, its opening is Lertxundi’s most traditional landscape image, a shot of mountains and brush that, via the gradual opening of the aperture, moves from silhouette (absence) to detail (presence). The second segment uses a smoothly moving camera to explore the space of an apartment, a site of pure presence that exists only to be occupied, the midpoint on a movement from absence through presence back to absence. Lertxundi closes with an image of downtown Los Angeles at sunset as seen from the hills of Silver Lake or Echo Park. The movement here is conceptual rather than optical, the smoggy materiality of a Los Angeles sunset eventually giving way to a realization that such a view of the city is, in its terrible, destructive beauty, only a concept, a romantic ideal that can never be present because it doesn’t exist in the first place. Having lived in Los Angeles for two years, this is often how I felt: those sunsets are where the dreams of Hollywood live, the false presence that attracts so many people and so much money every day, only to churn it all right back out as true absences. In the end, Lertxundi cannot open the aperture on this as she does on the natural; the fact that it isn’t even a possibility is telling enough in itself.

4. Lertxundi’s handling of pop music falls squarely under the sign of Bruce Baillie: My Tears Are Dry clearly acknowledges the influence of All My Life (1966) via the design of its title cards, and across all four films she prefers to place songs prominently in the front of the mix, often allowing them to play for nearly the entirety of their duration. As such, the music assumes a place of importance in her films that allows it to bring in the full weight of its own history; it exists as an equal with the image, rather than just emotional shading. That her most prominently placed songs have come from Leslie Gore, Hoagy Lands, The Blue Rondos, James Carr, and Robert Wyatt—all songs recorded before her birth in 1981—has led to readings of her work that situate it as fundamentally nostalgic. But like Bonello in L’Apollonide (2011), Lertxundi deploys ostensibly retro songs not as fetish objects of an irrecoverable past, but as a means for creating an any-time which mingles with the any-space of her Los Angeles, allowing her films to be specific in their images and sounds without linking concretely to an already-passed moment of creation. What results is a layering of the presence-absence dialectic: the eternal present of the film as whole masks and is supported by facts rendered absent by time, historical emissions allowed to retain their own presence. This ability to allow every moment to remain alive is one of Lertxundi’s major accomplishments.

5. Throughout Lertxundi’s work, the house proves to be a space of flux. This impermanence manifests itself in the physical decay of the cabin of Footnotes, the false unity of the interior in Tears, the centrality of the motel in Cry; only in A Lax Riddle Unit does a domestic space appear as really lived in. Though it might be tempting to find in this an ambivalence toward her status as an immigrant artist, the house-in-flux in fact proves to be a source of liberation, the necessary state for the free movement between the natural and the social that is central to her work. (Even the lived-in house of A Lax Riddle Unit is primarily a conceptual point on a large social continuum, and only secondarily a personal domestic unit.) Put simply, the open space of the house is always preferable to the closed space of the home.

6. This woman is Laida Lertxundi; it is her only appearance in her films thus far…

7. Lertxundi’s films are, without being overtly reflexive, among the purest examples of the work of making a film that can be seen anywhere today. Though she is not a structuralist, every shot reflects the conditions of its composition. Against a tendency, in films of both the avant-garde and the mainstream, to mask the reality of creating the image behind its beauty or grandeur, Lertxundi’s frames are simple and unadorned, the camera’s placement easily discernible, the light natural. Likewise, her montage, even when it creates a conventionally obfuscating effect as in My Tears Are Dry, makes no effort to elevate one image above any other—each retains its own truth. This material being is the basis of the presence that forms half of the central dialectic of Lertxundi’s work.

8. It is instructive to consider the meaning(s) of every word in this short declaration. You’re: The direct address of the audience again brings in the notion of presence, since it is impossible to address an absence in the second person (or, if the absence is directly addressed, it is as the true absence that is acknowledged as the first step of dealing with it in My Tears Are Dry). Leaving: As confirmed by Cry When It Happens, Lertxundi’s films radically confirm the centrality of the present. The acknowledgement of an occurring shift from a present-present situation to a present-absent situation, is, at least, a clear-eyed assessment of reality; a simple statement of fact, as unadorned as her images. Me: Here Laida Lertxundi and the viewer become one, the presence surrounded by an absence—as much the dark of the theatre as the past and the future. This is the point from which we begin. Her films are small, clear-eyed explications of nature as it’s obscured by society; the truths of an immediately, richly lived life tucked away in footnotes.

Phil Coldiron- « Previous

- 1

- 2