Global Discoveries on DVD | Presumptions & Biases

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

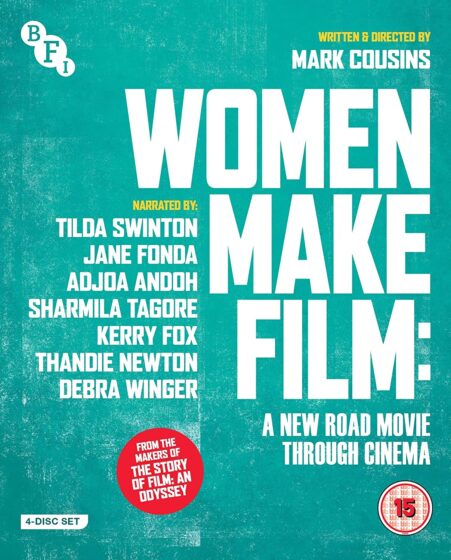

We already know from his imaginary conversations with his very own “Orson” in The Eyes of Orson Welles (2019) that the presumptions of Mark Cousins respect no natural boundaries apart from those of his own hubris. So he doesn’t even need to credit himself as the writer of the 14-hour marathon Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema (2018)—available on four Region B Blu-rays from the BFI containing ten chapters apiece—even when his text is being dutifully delivered by Tilda Swinton (as in the first chapters), or Jane Fonda, or another high-profile woman, because he knows that his credit as director and his characteristically friendly stream-of-condescension have already registered his fingerprints on every frame—which is literally true, insofar as his series’ widescreen aspect ratio reconfigures the compositions and frames of many of the films he claims to be celebrating. (Though I have to admit that Julia Solntseva’s The Golden Gates [1971], a tribute to the director’s late husband Alexander Dovzhenko, reconfigures the aspect ratios of Dovzhenko’s masterpieces no less ruthlessly and systematically than Cousins does with other filmmakers.) Meanwhile, the patter he assigns to Swinton et al. defines the significance, meaning, and value of every clip before we can begin to respond to it on our own—indeed, it precludes any sort of response from us apart from passive assent before we move on to the next clip. (Cousins shares with many other UK journalists the creepy capacity of always having something to say, even when it comes out as twaddle.) What this means, in effect, is that this alleged salute to scores of movies made by women is actually a form of self-congratulation for what one guy thinks that he thinks about them, while denying us (and, in some cases, the filmmakers themselves) an opportunity for any independent thoughts or judgments.

That said, I’m reminded of Gertrude Stein’s dismissal of Ezra Pound as “a village explainer: excellent if you were a village, but if you were not, not”—which qualifies as excellent dish if you’re a city snob, but if you’re not, not. So having thus dispensed with my bile, let me turn around and thank Cousins for introducing me, in his self-appointed role as village explainer, to so many underexposed films, proving that this is no mere recycling exercise like those tiresome American docs devoted to reheating the usual Oscar chestnuts one more time. Clearly by design, the first three clips are from films both memorable yet forgotten—Binka Zhelyazkova’s We Were Young (1961), Larisa Shepitko’s You and Me (1971), and Wendy Toye’s On the Twelfth Day… (1955)—and Swinton’s reading of Cousins’ commentary over the fourth clip, from Kira Muratova’s Brief Encounters (1967), finally taught me how to pronounce Muratova’s name correctly. On the other hand, Cousins is no Ezra Pound, even as an eccentric amateur when it comes to his grasp of film history (in his 15-hour The Story of Film [2011], his notion of cutting-edge avant-garde cinema is Matthew Barney and Lars von Trier, not Michael Snow or Hollis Frampton). If literary parallels are needed, an urban explainer like Washington Post book reviewer Michael Dirda is surely closer to the mark than Pound, but Cousins is considerably more schoolmarmish than Dirda in lining up his selected “study” topics, such as how a film director establishes “tone” or “believability” or “introductions to characters,” none of which I followed with much sense of urgency. In short, I’m grateful to Cousins’ clips as introductory samplers, but mostly indifferent to his deep-dish sound-bites about them—e.g., is Tanaka Kinuyo really and truly Japanese cinema’s Bette Davis, whatever that might conceivably mean? I neither know nor care.

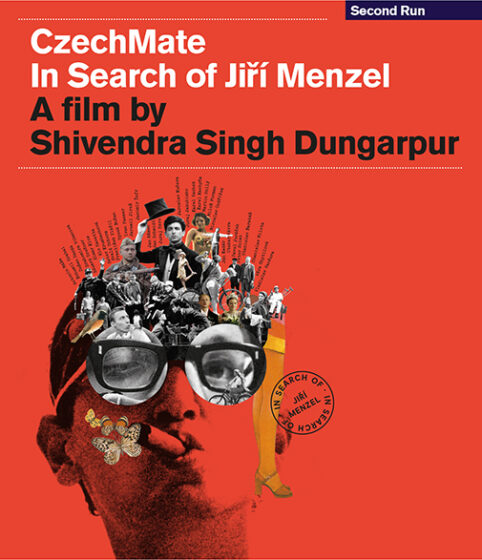

What a special pleasure it is, then, to turn from a big English label to a small one (Second Run Features), and from Cousins’ idle word-spinning to Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s masterful and enlightening 448-minute CzechMate: In Search of Jiří Menzel (2018, presented on two region-free Blu-rays), which, as with the director’s previous Celluloid Man (a 2012 documentary about film archivist P.K. Nair, also available from Second Run), proves to be much broader in scope than its title suggests. Taking Menzel’s 1966 Oscar-winner Closely Watched Trains (a film I barely remember, although now I’m looking forward to rediscovering it) as its starting point, the film expands into a portrait of the so-called Czech New Wave in which the major commentators are actually the major participants on the relevant films. (Apart from Menzel, those interviewed include Woody Allen, Věra Chytilová, Raoul Coutard, Miloš Forman, Agnieszka Holland, Juraj Jakubisko, Jaromil Jireš, Pavel Juráček, Emir Kusturica, Ken Loach, Jan Němec, Ivan Passer, Evald Schorm, and Andrzej Wajda, among many others.) What they have to say is almost always informative and/or illustrative about the films, yet the clips are usually allowed to speak for themselves, thus generally enabling us to observe and think for ourselves while watching them (a quality that Loach singles out as a particular virtue of the Czech New Wave in toto).

For me, the most valuable aspect of Dungarpur’s documentary is that it provided me with more of a context for exploring and understanding Věra Chytilová than anything else I’d previously encountered. I’d been looking for ages for her Pleasant Moments (2006)—a manic comedy (scripted by Chytilová’s own therapist) about marital discord, at once painful and hilarious, that I reviewed for the Chicago Reader 13 years ago—until I recently found that I could order it for $19.99 from czechmovie.com under its Czech title, Hezke chvilky bez zaruky (which translates, literally and awkwardly, as Nice Moments Without Guarantee). Then I discovered that one can order five other English-subtitled films of hers (three of them on all-region PAL DVDs) from the same site, for prices that are all over the map: Patrani po Ester (2005), a documentary about Ester Krumbachová—a “costume designer, screenwriter, director, [and] one of the boldest personalities of the Czech New Wave,” who was a major collaborator on such films as Chytilová’s Daisies (1966), Němec’s A Report on the Party and Guests (1966), and Jireš’ Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970)—for $39.99; a Region 2 DVD of The Inheritance or Fuckoffguysgoodday (1992) for $9.99; Ban from Paradise (2001), obscurely described as a “Czech Hollywood” film about nudists and apes, for $17.99; Calamity (1981), another comedy, for only $6.99; and Story from a Housing Estate (1979), Region 2, for $8.99. And to make things still weirder, apparently all these DVDs, like Pleasant Moments, come not in boxes but in thin cardboard sleeves, albeit carefully wrapped. On the same site, by the way, you can purchase three Gustav Machaty films: Ecstasy (1932), on sale for $14.99; From Saturday to Sunday (1931), for $18.99; and Erotikon (1929), for $14.99. (And here are two more helpful URLs that this site led me to: easterneuropeanmovies.com, and sovietmoviesonline.com.)

A word about my own presumptions and biases: I realize that it’s unfair and snobby of me, but I have a tendency to get prickly when a friend or acquaintance who’s never bothered to see or even considered seeing Jafar Panahi’s The Circle (2000), Crimson Gold (2003), or Offside (2006)—three of his best films (and, for me, three of the greatest Iranian films ever made), all made prior to Panahi’s 2010 arrest and ban from filmmaking—expresses enthusiasm for one of Panahi’s post-arrest, nice-try, small-scale efforts like This Is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013), or Taxi (2015). Why? Because however inadvertently or indirectly, this seems to validate the confinement and virtual silencing of one of Iran’s greatest filmmakers, and because, as far as I’m concerned, Panahi’s pre-arrest movies are easily ten times better, even if the public and libraries mysteriously appear to be less infatuated with them. To a lesser extent, I also blanch a bit when I encounter people who “choose” the French version of Max Ophüls’ Lola Montes (1955) on Criterion over the German version (spelled Lola Montez) on Munich Filmmuseum, usually without knowing that such a choice exists; or unknowingly “select” the Italian version of Roberto Rossellini’s India Matri Bhumi (1959) without realizing that the harder-to-access French version is substantially superior. For me, all this is roughly akin to the herdlike conviction that the ideal time to re-see a favourite actor or director’s films is immediately after she or he dies, presumably because that’s the easiest way of joining the crowd.

I have a related bias when it comes to all those books and documentaries about Nelson Algren—another abused underdog and political victim like Panahi—finding that I much prefer those with unwieldy, uncommercial, poetic titles, and a real passion for Algren’s politics: Colin Asher’s book Never a Lovely So Real: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren and the documentary Nelson Algren: The End Is Nothing, The Road Is All., directed by Mark Blottner, Ilko Davidov, and Denis Mueller. The latter came out in 2015, but I’ve just caught up with it, and I love the way the film’s title—a proper sentence—actually ends with a period, which may be about as uncommercial as any title can get (in addition to perversely suggesting that the end is actually everything). More generally, I like the tattered, raggedy quality of much of the archival footage (especially the home movies), which often makes it seem like a self-portrait by Algren; and the emphasis it places on Algren’s lyrical prose (which is reflected in that title) and affection for losers, which sometimes verges on what might be called a loser complex—or such is the impression left by Studs Terkel and Kurt Vonnegut Jr., the two talking heads and Algren pals in this film whom I find most persuasive. Indeed, the best thing about this documentary is that it gets too deep into Algren’s mindset to qualify as hagiography: it gives you some version of the man in all his painful complexity. (Though I do think it founders when it tries to trash Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm [1955] on its own terms and not only on Algren’s terms, though that’s perhaps inevitable when you weigh both literary and ethical concerns against Hollywood expressionism and star power.) The DVD is available for $24.95 from First Run Features, and it comes with many extras, mostly expansions or outtakes of the interviews.

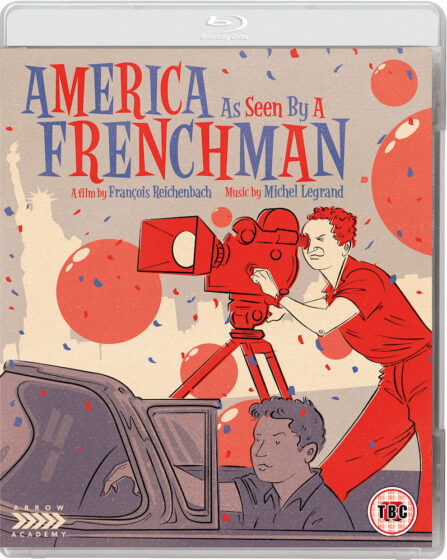

My first encounter with François Reichenbach (1921–1993) wasn’t via Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1973), which employed his extensive documentary footage of art forger Elmyr de Hory and notorious hoaxer Clifford Irving, but his 1960 L’Amérique insolite, a Cartesian celebration-cum-putdown of American fantasies of the Good Life that opens with a handwritten endorsement from none other than Jean Cocteau, who praises the film for its exposure of American disorder and its refusal to “play by the rules”—which makes me wonder if he’d make the same claim after the current pandemic. (Another notable contributor is Michel Legrand, whose score includes a song called “Marti Gras” co-credited to Chris Marker, as well as a glib rip-off of Miles Davis and Gil Evans that accompanies a segment on young male prisoners in Houston, Texas, that Legrand would himself rip off half a century later for his lamentable score for Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind [2018].) I’ve owned this film for years on a letterboxed VHS tape (it’s one of the only CinemaScope documentaries that I can think of), and, having revisited it recently on a new Arrow Academy Blu-ray (under the title America as Seen by a Frenchman), I now think it qualifies in some ways as a (possibly Marker-influenced) essay film avant la lettre—albeit one where one can imagine H.L. Mencken and Nathanael West serving as honorary executive producers rather than Alexis de Tocqueville, a far more discerning critic of the US. Don’t be fooled by the pseudo-scientific narration (delivered alternately by a man and woman) and the occasional neat aphorism (“America has nine million farmers but no peasants”): this parade of robotic theme parks, grotesque publicity shoots, pageants, rituals, and diverse oddball spectacles (loads of majorettes, scads of hula hoops, a school for strippers, a “convention” for twins) mostly adds up to a kinder, gentler Mondo Cane (1962), half satire, one-quarter freak show, and another quarter baffled admiration.

Over two consecutive nights, I had my first looks at two Anglo-American noirs boasting lousy titles and London settings, both directed by prolific, neglected actors-turned-directors, and both ultimately qualifying as Hollywood schmaltz (even if one is technically British) with intermittent compensations. The technically British item is The Good Die Young (Lewis Gilbert, 1954, on a BFI PAL DVD), a heist film worth seeing, if at all, for its cast (Laurence Harvey, Gloria Grahame, Richard Basehart, Joan Collins, John Ireland, Rene Ray, Stanley Baker, and Margaret Leighton) rather than its half-baked script. Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (Norman Foster, 1948, on a Kino Lorber DVD) has another good cast (Burt Lancaster, Joan Fontaine, Robert Newton), a better script (Ben Maddow and Walter Bernstein worked on the adaptation of Gerald Butler’s novel), music by Miklós Rózsa, cinematography by Russell Metty, and moves through much more striking spaces and evocative sets (by Bernard Herzbrun and Nathan Juran).

The BFI disc includes a public Q&A with Gilbert—introduced rather extravagantly by the director’s Alfie (1966) star Michael Caine—that has nothing to say about The Good Die Young, Alfie, or Gilbert’s later hit Educating Rita (1983), but a fair amount about Gilbert’s childhood in show biz and how difficult it was for him to work with Orson Welles on the 1959 adventure thriller Ferry to Hong Kong. The Kino Lorber disc has an audio commentary by Jeremy Arnold (which, based on my sampling, seems adequate but rather obvious), but more importantly, this release prompted me to conjure up one of my own extras: a brief research on the film’s director, Foster. A supporting actor and B-movie lead in the early to mid-’30s, Foster moved into directing with a number of Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan pictures; was married to two Hollywood leading ladies (Claudette Colbert and Sally Blane, the latter an older sister of Loretta Young); and was hired twice by Welles as a director (for the never-completed Mexican episode of It’s All True and for the 1943 thriller Journey into Fear) and once as an actor (he played one of the few likable characters in The Other Side of the Wind, the gumball-chewing Billy Boyle)—a show of wisdom on Welles’ part that somewhat makes up for his dreadful, would-be comic performance as a stuffy English captain in Ferry to Hong Kong.

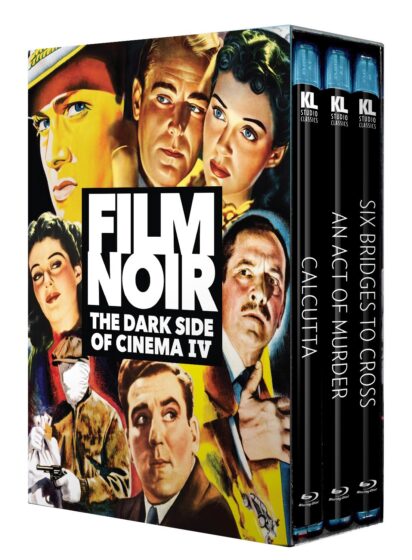

Sometimes it becomes necessary to distinguish between “noir” as a vague genre category and “noir” as an advertising term, which its vagueness as a genre category undoubtedly assists. I’m not sure which of these it was that inspired me to ask for review copies of Volumes III and IV of Film Noir: The Dark Side of Cinema from Kino Lorber Classics, each of which contains four Blu-rays, but as soon as I started out with Joseph Pevney’s 1955 Six Bridges to Cross (scripted by Sydney Boehm, shot by William Daniels, and with a dopey theme song performed by Sammy Davis Jr.) I discovered that it isn’t a noir at all: its generic identity is better described as a crime story filmed largely on locations, like Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street (1945) and Call Northside 777 (1948), Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) and Thieves’ Highway (1949), Elia Kazan’s Boomerang! (1947) and Panic in the Streets (1950), or even George Sherman’s more noir-ish The Sleeping City (1950), a Universal release (like Bridges) that is included in Volume III of the Kino Lorber set. This leads me to recall my critique of what’s commercially alluring about noir (to myself and others), as I recently put it to The Chiseler’s Daniel Riccuito: “I don’t find noir more ‘realistic’ than ’30s leftism. Au contraire, I find its defeatism and expressionism far more comforting. Closure, no matter how grim or grimy, is always more comforting than ellipsis and suspension—trajectories into possible futures. I think the popularity of noir today has a lot to do with a doom-laden death wish, a desire to escape any sense of responsibility for a future that seems helpfully hopeless—an attitude that ‘blossoms,’ decadently, into the Godfather trilogy, where corruption is seen as ‘tragically’ (that is to say, satisfyingly) inevitable. Once the future becomes foreclosed, we’re all let off the hook, n’est-ce pas?”

Yet to complicate matters, I’m glad that the noir label tricked me into watching Six Bridges to Cross. Its subject is the fluctuating friendships between a Boston cop (George Nader) and a couple of crooks (first Sal Mineo, then Tony Curtis), and what keeps it interesting is that it’s sufficiently ambiguous to make us keep shifting our sympathies and alliances, not only in terms of whom we believe but also in terms of whom we want to believe. And whomever we side with, there’s nothing remotely doom-ridden or fatalistic about our alignments or theirs, apart from the formulaic conclusion, which feels like a directive from the Hays Office.

Universal’s 4K restoration of John Ford’s first feature, Straight Shooting (1917)—a Western with Harry Carey, Molly Malone, and Hoot Gibson that the director made when he was still calling himself Jack Ford—has the merit of utilizing two of the very best Ford commentators, Joseph McBride and Tag Gallagher, to optimal effect. The former delivers an audio commentary and the latter provides both a 12-page booklet essay and an audiovisual essay entitled “Bull Scores a Touchdown.” There’s also piano accompaniment by Michael Gatt on this Kino Lorber Studio Classics Blu-ray, along with a surviving fragment from Ford’s postbellum Southern drama Hitchin’ Posts (1920).

I’ve been clamouring for ages that we should have a box set devoted to Susan Sontag’s four features, although I suppose that, because of diverse rights issues, we never will. It’s worth reporting, however, that ubu.com currently has three of them available in streaming form: a lousy but English-subtitled copy of Duet for Cannibals (1969), her least interesting and least ambitious film (which is now available in a much better DVD copy from Metrograph/Kino Lorber, along with a Wayne Koestenbaum audio commentary that seems to regard this brittle comedy mainly as a series of footnotes to Sontag’s sex life, complete with a picture of Sontag on the cover—rather than any of her actors/characters—to amplify this obnoxious approach); Promised Lands (1974), her documentary about the Yom Kippur war (which is also available on DVD, from KimStim); and her long-unavailable Unguided Tour (1983), co-starring dancer Lucinda Childs, which is presented in unsubtitled Italian (though you might be able to track down English subtitles on the internet, as I did).

Sontag’s most interesting and ambitious film, Brother Carl (1971), which is also her only one entirely in English—even though the cast members are mostly Swedish, and the most particularly impressive (Laurent Terzieff) is French—remains the hardest to see by far. But I finally tracked down a Swedish DVD on the Svenska Filmpärlor label (which I ordered for $26, including postage, from papercutshop.se), which is happily free from the gossipy clutches of Koestenbaum or his eager facilitator, Sontag biographer Benjamin Moser, both of whom share with the Paul Schrader of Mishima (1985) the dubious view that narrative art is chiefly interesting and important because of its autobiographical and psychosexual subtext. I wouldn’t call Brother Carl an artistic success, exactly (unlike the more modest and much more charming Unguided Tour; check out Gary Indiana’s article in the November 1983 Artforum for an informed appreciation), but it’s certainly packed with ideas, filmic as well as philosophical: James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and Carl Dreyer’s Ordet (1955) are two of its clearest inspirations and reference points, as well as Bergman at his most tortured (and torturous). Which is another way of arguing that Sontag’s films, whatever their limitations, deserve to be considered as art, not as some form of disguised autobiography (a genre that she hated).

In closing, I’d like to call attention to two European double-feature releases that I contributed to: Jackie Raynal’s Hotel New York (1984) and New York Story (1980), on a Re:Voir DVD from France (a reprinted excerpt of my interview with Raynal, conducted with Sandy Flitterman, is part of the 36-page booklet); and Masumura Yasuzo’s Black Test Car (1962) and The Black Report (1963) on an Arrow Blu-ray from the UK, for which I wrote and narrated a video appreciation. I also wrote an original essay for Grasshopper Film’s DVD and Blu-ray of Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela (2019), which should be out by the time this column reaches print.

Jonathan Rosenbaum- « Previous

- 1

- 2