Exploded View | Peter Emanuel Goldman’s Pestilent City

By Chuck Stephens

Structurally ambiguous and romantically rancid, Peter Emanuel Goldman’s 1965 Pestilent City is a 15-minute, high-contrast black-and-white New York City scherzo of sleaze, dereliction, working stiffs, stumblebums, loitering, malingering, playing, and passing out, filmed in Times Square and along the Deuce during the area’s deleterious decline, halfway between Sweet Smell of Success (1957) and Taxi Driver (1976). It sticks in your head and beads on your skin the way Sleazoid Express did the first time you read it. It’s like the omnipresent smell of piss in the New York City of the ’70s. Foul and beautiful and bare.

Lauded by Susan Sontag and Jean-Luc Godard while he was still carving a small niche in the independent/experimental New York film scene of the late ’60s, Goldman went on to various other careers (political activist, diplomat, documentarian, memoirist) after his filmmaking moment faded. His work has received overdue attention of late, including two Re:Voir DVD releases of his features, Echoes of Silence (1965) and Wheel of Ashes (1968). Though both lensed in impromptu and street-real ways of their own, the features stand apart from Pestilent City, which seems to proceed on some stoned, headlong lurch known only to itself. Vacillating between negative and positive printing, and interpolating swathes of photojournalistic art-stills and throat-grabbing headlines (“Woman, 81, Raped in Bronx”), Goldman’s short has been rightly recognized (by Max Goldberg and others) as an uncanny precursor to Scorsese’s Taxi Driver: not just in its lumpen, bottle-in-a-brown-bag milieu, but particularly in the way its often aleatory soundtrack is underscored by bowed, lugubrious strings heard at half-speed—precisely the effect that Bernard Hermann’s 1976 theme so hauntingly attains.

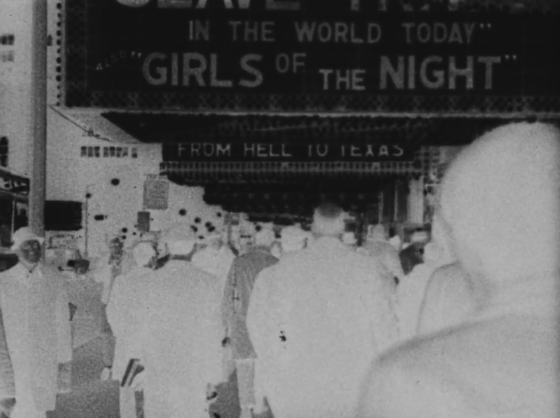

Anyway, Pestilent City. It’s on Vimeo, it rocks, check it out. Use this as a cheat sheet before you go:a list of film titles glimpsed on movie-theatre marquees in Pestilent City: Girls on the Loose (Paul Henreid, 1958), Girls of the Night (Maurice Clochet, 1958), Slave Trade in the World Today (Maleno Malenotti, Roberto Malenotti, Folco Quilici, 1964), From Hell to Texas (Henry Hathaway, 1958), Hollywood’s World of Flesh (Lee Frost, 1963), Ordered to Love (Werner Klinger, 1961), The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (José Quintero, 1961), Rome Adventure (Delmer Daves, 1963), Father Goose (Ralph Nelson, 1964), Guns at Batasi (John Guillermin, 1964), My Blood Runs Cold (William Conrad, 1965), Devil Doll (Lindsay Shonteff, 1963), Olga’s White Slaves (a.k.a. White Slaves of Chinatown, Joseph P. Mawra, 1964), Body of a Female (John Amero, Michael Findlay, 1964), Witchcraft (Don Sharp, 1964), The Man Who Walked through the Wall (Ladislao Vajda, 1959). Additional, currently untraceable titles seen in Pestilent City: Trigger Happy Gang Girls, Killer Cory, White Slavery, Girls Incorporated, Where Love Goes Skin Deep. Sadly, Broadway smash I Had a Ball starring Buddy Hackett was never made into a film. (PS: Fuck lists.)

Finally, let us turn to French cinephile and author Philippe Azoury, who has published a rapturous essay on Goldman (at play-doc.com) in which, upon recognizing Pestilent City as a “cry of rage tossed at the throat of New York, shot as an inhumane city, in slow motion and in the negative,” he admits that “Goldman appeared to me as a loony Murnau coming from the night of time, bringing again to the ’60s—with the violence of youth culture and the brutality of underground—the great debates between silent cinema, the cinema of the force of the face, and photography, the power of still images.” Cool. Never mind Nosferatu (1922) though, as, better still, Azoury then appends this lovely linguistic anecdote: “Goldman married a young Danish woman, Birgit Nielsen, who had a role in Wheel of Ashes, his third feature film, which he shot in Paris in 1967-68 thanks to a grant he received through Jean-Luc Godard. The film, shot in seven weeks with Pierre Clémenti in the main role, reflects a mystic crisis. Pierre Clémenti, who, just as so many French people at that time, did not speak English, understood the title in a totally different way: ‘We Love Hashish.’”

Chuck Stephens- « Previous

- 1

- 2