Exploded View | Ed Emshwiller’s Thanatopsis

By Chuck Stephens

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language…

—Thanatopsis, William Cullen Bryant, 1811

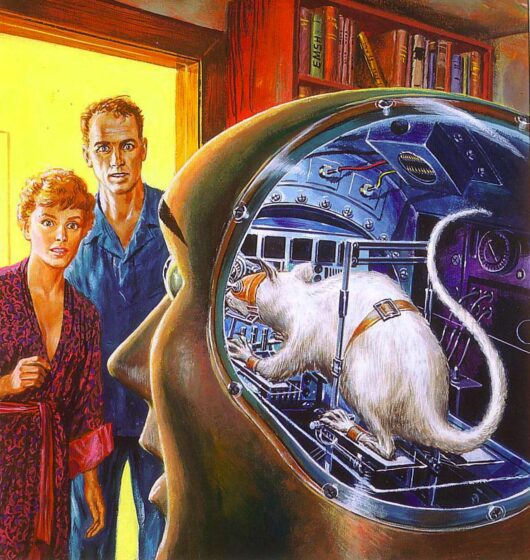

A buzzsaw in turbulent neon; a heartbeat and a hummingbird; a flickering flame mistaken for a cosmic streetwalker by a god/man with the clammy, impassive stare of a regular patron in the go-go bar at the edge of forever. Thanatopsis (1962), 20th-century Renaissance man Ed Emshwiller’s 16mm cine-dance classic, may be titled after W.C. Bryant’s 19th century “vision of death”—in which nature organically reclaims and obliterates us all—but it remains one of the liveliest and most kinetic touchstones of ’60s cine-dance. A precursor to Bruce Conner’s Breakaway (1966), with one toe-shoed foot smudging Jules-Etienne Marey’s motion studies into modern dance-recital blurs while the other takes a space-booted step into the fourth dimension, Thanatopsis bridges the worlds across which Emshwiller travelled. A master illustrator of pulp science fiction long before he began his career in experimental film and video, the Michigan-born, École des Beaux Arts-trained “Emsh” (1925-1990) created more than 400 cover paintings and countless interior illustrations between 1951 and 1979 for s/f mags like Galaxy and Astounding Science-Fiction: ravening bug-eyed beasts, scantily clad she-demons from the far reaches of the universe, and human-like constructs revealed as remote-control vehicles for mastermind rodents. The debts that the imagery of science-fiction cinema, television, comic books, and record album covers during the latter half of the 20th century owe Emsh—winner of five Hugo awards and a posthumous Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductee—are uncountable. Documentary footage he shot of Bob Dylan ended up in D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back (1967). Oh, and he taught at Yale, Cornell, and UC Berkeley, and retired as Provost and Dean of film and video at CalArts.

In Thanatopsis, a man (Emsh’s brother Max) appears in a series of medium close-ups, staring not exactly blankly into who knows exactly what, his pitted complexion harshly lit, the sort of rugged and fascinating terrain upon which Brueghel the Elder, long before Tarkovsky or Tarr, might have trained a gaze. Around the man a woman (Becky Arnold) is pirouetting in constant hyper-motion, animated entirely into abstraction; we see only the chimerical streaks and smears of a tweaker Tinkerbell in a bright white leotard. His gaze never fixes her; barely seems to intersect with her movements, and though brooding seems wholly unimpressed. In any event, she will not be fixed. Her leotard changes from black to white, she merges with the neon squiggles of the night. The buzzsaw sings ever louder, then stops altogether; the heartbeat thumps dully on. If we could peer inside this man’s head, would we find a chittering rat inside? Could we slow her whorl, would we see beyond the stargate that separates their worlds? “Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past/All in one mighty sepulchre.” Dance, death, dance.

Chuck Stephens- « Previous

- 1

- 2