Some Kind of Monster: True/False 2013

By Eric Hynes

The new word was politely forced upon me, the result of fraught late-night deliberations not unlike those between expectant parents. In fall of 2012, I was commissioned by the programmers of the True/False Film Festival (festival founders Paul Sturtz and David Wilson, along with associate Chris Boeckmann) to curate four historical films for a series at the Ragtag Cinema in Columbia, Missouri, that would partially coincide with the festival. In time for its tenth anniversary, True/False was looking to explore cinematic antecedents to the kinds of formally frisky contemporary documentaries it had been championing. I’d selected films from among a group of what might be called “hybrid” documentaries from New York in the late 1960s, but the T/F programmers took some understandable exception to a term that was more suggestive of eco-conscious cars than ambitiously unwieldy nonfiction films that stomped all over the border between fact and fiction, documentary and narrative, entertainment and experimentation. The term chosen instead, and subsequently inserted into my program notes, was chimera—a Greek mythological derivation connoting a hydra-headed monster and denoting something otherwise unclassifiable.

Not exactly a trending Twitter tag in the making, but certainly more evocative of the woolly cinematic beasts at hand. I myself felt rather chimeric in regards to True/False this year, being as I was functioning as a writer-in-residence guest of the rep house, a programmer/host of a festival-associated film series, and a critic on assignment for this publication. By extension, what follows will necessarily reflect my interpolated perspective, hopefully productively.

When Sturtz, Wilson and Boeckmann first approached me about curating the first of what will be an annual critic’s series—appropriately/equivocatingly entitled Neither/Nor—they had already done preliminary research into New York films from the 1960s, but I was encouraged to set my own parameters, to go beyond that location and time frame or to select another focus entirely. However, I was just as drawn to that specific film-historic moment as were they, both for its abundance of formally unwieldy movies and for the remarkable singularity of that abundance. While cinematic chimeras are as old as the cinema itself—from Edison’s docu-performed demos and Méliès’ recreations of current eventsthrough to Flaherty, Buñuel, and beyond—it seemed to me that any search for an antecedent of what True/False was championing should start at the moment of their Media Age explosion, when synch-sound portability endowed cinematic engagements both great and small with vastly expanded potential.

What I determined when discovering and revisiting dozens of relevant titles from the New York ’60s is that this chimeric ground zero could be further narrowed to films shot during a 16-month period, from mid-1967 to late 1968. In the end, the films we selected for the program were Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), Peter Whitehead’s The Fall (1969), Williams Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), and Pennebaker/Leacock/Godard’s 1 P.M. (1971). However, there was a murderer’s row of others—including Jonas Mekas’ The Brig (1964), David Hoffman’s King, Murray (1969), Shirley Clarke’s The Cool World (1964) and Portrait of Jason (1967), Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969), Robert Frank’s Me and My Brother (1969), McBride’s My Girlfriend’s Wedding (1969), and Norman Mailer’s Maidstone (1970)— that, each in their own way, spoke just as powerfully to this uncanny moment of confluence—a time when a certain pocket of American cinema began to reflect and explore its historical, societal and moral context through formal flux, narrative diffusion, and the merging of utopia with dystopia, personal with political, man with movie camera.

With these films as a kind of standard for docu-cinematic delirium, it becomes tempting to judge all of True/False programming according to that standard. While this may be a somewhat reductive or misguided impulse (the implications of which I’ll explore shortly), it nevertheless speaks to True/False’s unique place within the festival landscape. Not just another doc survey, industry marketplace, or act of small-town self-promotion, T/F has a genuinely critical slant—and one that, by now bringing critics into the curation process, implies an ongoing interrogation of the art (and act) of documentary filmmaking rather than just a showcasing of the year’s more appealing fare. At least potentially, it’s programming as scrutinizing rather than cheerleading, inviting critical engagement not just with the chosen films but also with the choosing of those films.

With that in mind, it’s hard not to survey the global festival landscape for “True/False films” and expect T/F programmers to duly lay claim to them—and while it’s a tad strange to think of a festival having a claim of ownership over films it didn’t premiere, it’s understandable for one with such a uniquely discernible POV. In this light, the presence in this year’s slate of a totalizing art object like Leviathan felt less like the latest stop on the film’s extended festival tour than a triumphant homecoming—an impression furthered by the fact that the filmmakers, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, were coronated with this year’s career-spanning (after just two features!) True Vision Award. Other natural “True/False films” that made this year’s program, chimeric whatsits one and all, were Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, Tinatin Gurchiani’s The Machine Which Makes Everything Disappear, and a double shot of Gael García Bernal with Pablo Larrain’s docu-fictional No and Marc Silver’s ficto-documentary Who Is Dayani Cristal?

But once one truly buys into the slash at the (literal) centre of True/False and the intriguingly liminal state it denotes, it can be hard to countenance films that don’t actively challenge their own veracity, that don’t make overtly subjective art of filmic observation. The more that True/False puts into celebrating (and indeed defining) such cinema, the odder it feels to encounter such slickly ordinary social-issue docs as Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s Blackfish and Andy Heathcote’s The Moo Man in this year’s slate. Though I was a bit crestfallen to find a film as formally utilitarian as the latter in this year’s mix, it’s hard to argue with 1,700 people turning out at 10:30am on a Sunday morning to see a film in which a gentleman English farmer coaxes calves out of a legion of breaching cows. Such is the goodwill fostered by T/F, however, that Columbia audiences turned out as readily for the diffuse but surprisingly well-constructed Russian revolutionary omnibus Winter, Go Away or the morally disorienting, payoff-resistant Stockholm-syndrome two-hander The Captain and His Pirate as for such (relatively) unambiguous entertainments as the Heathcote film. That said, it’s still worth asking if these adventurous Columbianites needed such a soft landing place within the program, and furthermore, if it was necessary that more than half of this year’s new releases have come pre-sold from Sundance. Given the high quality of T/F 2013 films that were new to North American audiences—several of which were bypassed by that ostensible standard-bearer in Park City—such coattail-riding seems rather needless for a festival with such a highly developed identity of its own.

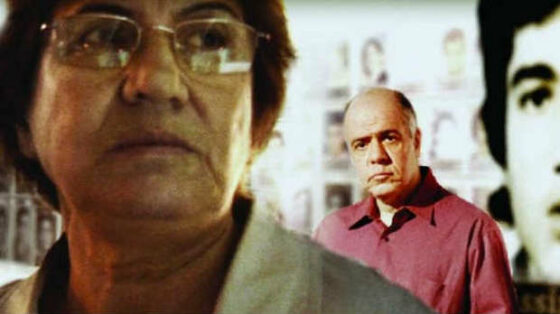

That identity was amply attested to by Eliane Raheb’s debut Sleepless Nights, an out-of-nowhere knockout that brilliantly combines moral tenacity, indefatigable reportage, ingenious interpersonal manipulations, and cop-to-the-construct formal reflexivity in pursuit of some measure of resolution in post-civil war Lebanon. Though the film’s two subjects—Maryam Saiidi, a woman still searching for her son who went missing three decades before, and Assaad Shaftari, the guilt-ridden officer responsible for the boy’s disappearance and hundreds of other wartime deaths—are each haunted in their own way by the events of the conflict, Raheb forcefully shows how the state-fostered efforts at South African-style “truth and reconciliation” rig things in favour of the hangdog, semi-contrite ex-ax man as against the grieving, genuinely victimized mother, who is advised to “move on” while her son’s murderer continually refuses to disclose the location of the boy’s remains. Raheb, who occasionally appears on screen to pursue and cajole her subjects (and weather their understandable resistance), yokes her filmmaking to moral purpose in astonishing ways, from a puppet-mastered confrontation between Shaftari and Saiidi to an eyewitness denouement that’s as brutally poetic as it is pointedly abrupt.

Just as pointed was the exquisite heartbreaker The Last Station, which empathetically observes the residents of a Chilean old age home. Directors Cristian Soto and Catalina Vergara make lyrical use of static and tracking shots, and discover a character for the ages in a butterscotch-voiced short-wave radio host who personally records and transmits the faraway sounds of ocean waves and mountain winds to his rapt, sedentary listeners. But what gives the film its sting isn’t its depiction of encroaching mortality, but rather the indignity of experiencing it as a cast-off from the living. In its own way, the elliptical, beautifully shot Northern Light, the directorial debut of cameraman Nick Bentgen, also contemplates that time-marking that comprises so much of our lives as it regards the various ways that the hard-working and -playing denizens of snowy Northern Michigan commit themselves toseasonal competitions, be they high-stakes snowmobile races, cheerleading exhibitions, or bodybuilding flex-offs. Though not exactly clinical, Bentgen’s camera nevertheless remains a touch too removed, never quite reconciling the indelible landscapes it captures with legible portraiture. But I’ll not soon forget the durational brilliance of an extended fixed shot of a snow-suited timekeeper on a frozen lake patiently waiting as a snowmobile zips into and out of view, its roar slowly fading into the wintry quiet and then reviving before the vehicle comes speeding through the frame again, as tedious and entrancing as a clock.

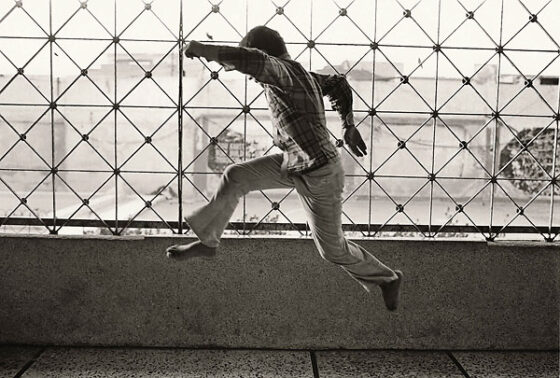

But the film that perhaps best embodied True/False’s privileging of artistic process was a film that I first encountered at the festival in 2012. A year after debuting as a work-in-progress, Omar Mullick and Bassam Tariq’s These Birds Walk was invited back and presented anew, with a less digressive narrative and more articulated characters (which were evidently to the film’s benefit, as it netted a US distribution deal with Oscilloscope Pictures shortly before the festival ). In last year’s dispatch, I wrote that the film “intertwines painfully recessive verité with an almost florid lyricism,” and while that remains true, the new version better showcases the exquisite, fleeting beauties that Mullick and Tariq captured in their extensive recordings in and around a Pakistani orphanage—particularly a breathtaking handheld dash into an impossibly thronged mosque to track an impulsively scampering, Cagney-faced orphan named Omar. While I hadn’t any issue with last year’s shaggier assemblage (though then again, I also saw no issue with enthusiastically subjecting a blizzard-beset, pre-festival Columbia audience to the notoriously shambling and downright cacophonous 1 P.M.), I found myself just as enamored with the artistry and humanity of These Birds Walk 2.0, and deeply appreciative of the extraordinary opportunity that True/False had afforded to experience a film’s process of becoming.

Even though notions of documentaries as bearers of unfiltered truths—via verité or other apparently unvarnished strategies—have long since been called into question, there still exists a certain discomfort with the idea, or rather the fact, of the constructedness of nonfiction cinema, and with those works that call attention to the fact that they are merely versions of realities rather than impartial distillations of them. Rare are the chances to constructively counteract that discomfort, to dignify the aesthetic choices that go into the creation of a narrative and an audiovisual presentation. Not every documentary is an overt chimera (or hybrid, hydra-head, whatsit or whatever), but they are of course all constructions—Frankensteins of various shapes and sizes, variously willing to reveal, flaunt, and scrutinize their seams. At True/False at least, this truism is treated not as a dirty secret but as the genesis of inquiry and appreciation. In his pre-screening introduction of After Tiller, a film whose subject—the endangerment of late-term abortion practices in America—required heightened security at the theatre, T/F’s Wilson spoke not of the polarizing issues at hand, but of craft and form. It would be foolish to suggest some connecting thread between, say, After Tiller and Leviathan (or to assert that T/F was asserting one), but such attentiveness to cinematic artistry, regardless of subject, is what stitches together this annual four-day festival into an ever-mutating chimera of its own.

Eric Hynes