Antoine Bourges on East Hastings Pharmacy

By Michael Vass

When Paris-born filmmaker Antoine Bourges moved from Montréal to Vancouver in 2006, he ended up living and working near the infamous Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. This led Bourges to make a pair of films in the community with its residents: the short Woman Waiting (2010), and the medium-length 2012 feature East Hastings Pharmacy, which depicts daily life at a methadone pharmacy. (Both films were made with Bourges’ producing partners at the Toronto-based production company MDFF, filmmakers Dan Montgomery and Kazik Radwanski, whose feature debut Tower premiered at Locarno earlier that year). East Hastings Pharmacy premiered at the 2012 Cinema du Reel Festival in Paris and has screened widely at festivals, including the Viennale, the Images Festival, RIDM, and the Kasseler Dokfest, where it recently won the festival’s top prize, the Golden Key.

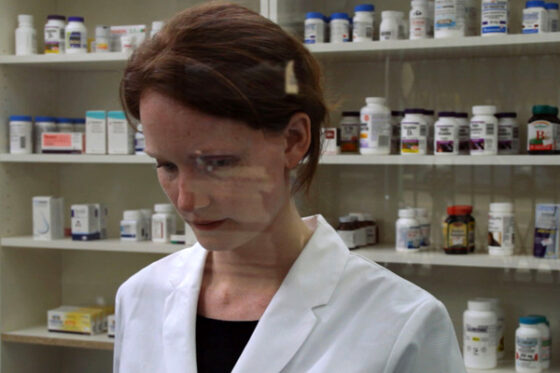

Bourges’ status as an informed, curious outsider, not just in relation to the marginalized Eastside community but also to Vancouver as a whole, contributes to his unique approach to his controversial subject. Simultaneously a fictionalization, a reconstruction, and a documentation, the film was shot on a pharmacy set built in an empty storefront on East Hastings Street, just a few doors down from the actual methadone clinic Bourges passed by every day. (As the closing credits detail, it “was made through collaborative improvisations and reenactments with residents of the Vancouver Downtown Eastside and actress Shauna Hansen performing as the pharmacist.”) As Aliza Ma wrote in an earlier post on the film for Cinema Scope Online, through this novel method “Bourges creates not a portrait of social reality but a trompe l’oeil that reaches even further towards an irreducible reality”: he films the pharmacy as a site of profound and mysterious human interaction, allowing the humour, even the charm, of the place and its clientele to emerge alongside the unavoidably unsettling realities. At once rigorous and open-ended, East Hastings Pharmacy is fascinated but never intrusive, respectful but never sentimental, empathetic without pity or condescension.

My interview with Antoine Bourges about the film took place via email over a period of a few months. It has been condensed and restructured for publication.

CINEMA SCOPE: Let’s start with how East Hastings Pharmacy was conceived and executed, because I think that its unique form is in large part a result of the logistical challenges that you came up against as you were developing the film. Can you give a history of the project and your shifting conceptions of it?

ANTOINE BOURGES: I had been living around the Downtown Eastside for a few years before I began to pay attention to these pharmacies. They are so much a part of the neighbourhood that they easily go unnoticed, which is probably what first intrigued me about them. One day I decided to venture into one. I didn’t know anything about the methadone program and became quite captivated by the activities and interactions that were taking place. There were line-ups of clients coming for the same cups of colourful medication in a very ritualistic manner; sometimes in silence, at other times it was more lively. I started going to the same pharmacy on East Hastings Street at different times of the day to see how many people were in the waiting room, and what they were doing. A pharmacy technician later told me that he thought I was an undercover cop trying to pinch one of their clients! The desire to make a film about these places came quite naturally, and my initial conception was to film in one of these pharmacies. At that stage, I had a relatively classical documentary conception in mind, although I remember already playing with the idea of mixing straight observational filming with more scripted scenes.

However, after a few months of meeting different managers and owners, I couldn’t get permission to film in any of these pharmacies (for various logistical and legal reasons). Because I come from fiction filmmaking, my thinking was that if we could not shoot on location, we could always shoot on a set. I never considered that this switch would diminish or betray my initial conception, because my approach had never been to document a specific pharmacy. I wanted to represent these places in the medium of film, and I knew that a transformation would take place whether or not I used a real location. We rented a commercial space on East Hastings Street for a month and a half and built a replica of an actual pharmacy that was on the same block. Obviously this altered the preparation of the project since, instead of working with the ongoing life of an actual pharmacy, we had to more or less construct every scene. This called for a complete collaboration with Eastside patients willing to take part in the project.

SCOPE: It could sound surprising that the shift from a more traditional documentary to something semi-fictional and staged on a set didn’t alter your basic conception much, but after seeing your film this makes sense. I think the strength of your approach is that it effectively makes it impossible to separate the documentary elements from the fictional elements, leaving the issue as an open question. Can you comment on this?

BOURGES: I never really understood this notion of real in cinema. If a simple camera placement suggests an intention, a fragmentation, and ultimately a position taken in regards to the world, it is hard to imagine how this capturing of “vérité” is even remotely possible. It simply didn’t make sense to try to highlight this divide between “real” and “staged,” or jump back and forth between them in a noticeable way. My interest in making this film was simply to represent my own sensibilities with regards to a place that I found profoundly mysterious and captivating. The “real” is more of a feeling, or a sense of reality that comes from the colours, the air, the texture of the soundscape of this neighbourhood. I wanted to somehow make this tangible through film. Working with actual Eastside residents and having the set on East Hastings Street was very important for this reason. As you can imagine, there are certain elements that called for a more documentary approach.

But I think the use of more constructed elements contributes to this same effort. For instance, the film adopts one of the most basic devices of fiction filmmaking, continuity. Through the use of editing and sound, events that have been filmed in different places or over many weeks can be put together to create a seamless, continuous moment. Using continuity felt necessary because I wanted to account for my experience of duration in these places. There was a certain quality in the rhythm intrinsic to these pharmacies that felt at once very regulated and at the same time separate from the outside world. Representing this rhythm meant constructing it.

SCOPE: Whydid you decide to cast an actor in the role of the pharmacist?

BOURGES: We couldn’t find an actual pharmacist able to put in the time necessary for the filming. I met and considered people of different professions to take on this role, and eventually chose an actress, Shauna Hansen.

SCOPE: How much of the film was scripted? How did you structure the improvisations?

BOURGES: I had prepared a loose script that I constantly adapted to the different clients that were available to come and shoot every day. Sometimes I would give them no directions and simply ask them to repeat actions I’d seen them doing. Other times I worked with them and Shauna more actively to create small narrative moments using their own experiences, along with my scripted notes based on the observations I had made during pre-production. There was no strict method, we had to adjust to each person and each scene.

SCOPE: What do you see as the ramifications of this more constructed approach in terms of representing the subjects in your film—members of a marginalized community who are portraying themselves, or versions of themselves?

BOURGES: Indirectly, I think embracing this more staged approach helped me negotiate some concerns I had about representing subjects in documentary. There is an underlying assumption when working in documentary that the subject is what you see. I think the relationship with the subjects here ends up being slightly different. By collaborating with the Eastside performers and letting them act and reenact their everyday actions, the film is only offering the viewer some possible narratives of their lives. I don’t think they are showing their “true selves” so much as their own evocations of themselves (or whoever they chose to portray). During filming, some of the performers were taking it quite seriously while others saw it as a game; in every case, however, they each had to make the conscious decision to come to our set and create the boundaries they felt comfortable with. So the film is not so much saying “this is what this person is like,” but rather, “this is what this person is kind of like, or could be like, but you’re obviously not getting the whole picture.” Ultimately, I think it was important to give this space to the participants considering the nature of the situations portrayed in the film.

There is an exception amongst the pharmacy clients that I think is worth mentioning. One of the situations I wanted to portray was that of a person coming in conflict with the pharmacist and the procedures of the methadone program. When doing research, I’d observed many instances when clients were struggling to deal with the constraints of having to intake their medication at the pharmacy, as opposed to doing it at home. I once saw a woman being refused her dose because the computer indicated that she had already come by earlier to take that same medication. This was hard to watch because I could tell by this woman’s distress that this problem was having heavy consequences on her life. For the purpose of the film, I could not find an actual pharmacy client that would work for this scene. I ended up finding Karen, a woman from the Eastside who had never set foot in these pharmacies and had never been on any drugs. Karen had an extraordinary ability to perform. Over a few days, her and Shauna worked to create a scene where she came in to ask for a few days’ worth of methadone to take home in order to go visit her son in a distant town in B.C. However, her attempt proves unsuccessful. Karen was not even a mother, so the scene was completely fictional. Upon showing a copy of the film to an actual pharmacist, I told her that it had been inspired by the time she could not give medications to a client because of a computer error. The pharmacist explained that there was no error: the client in question was in fact known for going to different pharmacies to get more doses of methadone (most likely to re-sell it on the streets) and all the pharmacists in the neighborhood apparently knew of this performance of hers. So by being a complete fiction, Karen’s performance is probably as close to reality as any other scene in the film!

SCOPE: One thing I especially like about the film is the way in which its basic structure acknowledges a certain unbridgeable distance between the clients and the pharmacist. As the only character played by a professional actor, the pharmacist functions in part as a surrogate for both you the filmmaker as well as for the likely audience of the film. The first shot of the film is of the pharmacist’s window, which mirrors the movie screen (it even has a similar aspect ratio). This window that separates the pharmacist from her clients is a very blunt and effective way to acknowledge the limits of what can be achieved in terms of “understanding” the experience of the clients; it ensures that we remain aware that we are observing them through a screen, and that their struggles are being staged for us in a very specific context. Likewise, for the clients, the pharmacist inhabits a world that is so remote from their experience that it must seem almost hypothetical. They are in the same small space, and yet the pharmacist’s window divides that space into two distinct realities.

BOURGES: The discussions I had with the pharmacists earlier in the process played a large role in how I conceived of the film. As I expected, a lot of their stories touched on this distance between them and their clients. The subject of trust often came up. While these pharmacists had a fondness for a lot of these people—they see them day after day, over many years—they were very wary. At one point or another, these pharmacists had all been betrayed in their trust because of what they described as the remnants of “junkie mentality” in some patients. I found it interesting to realize that the distance I had observed did not just stem from the impossibility of understanding the world of these clients, it was also one they consciously created in order to protect themselves. I tried to integrate this dynamic into the film. While I knew that the average viewer would probably identify more with the pharmacist than the clients, I wanted the pharmacist to keep a certain opacity so as to not reveal herself to us (the viewers) more than she would to her clients. It was important that we experience the distance that they feel from her too.

As you noted, the ultimate distance comes from the protective glass. What struck me when I first set foot in these pharmacies was how manifestly the presence of this Plexiglas demonstrates the larger marginalization of Eastside residents in the city. After my dialogues with pharmacists in the neighbourhood, I started to see this partition differently: as a wall that pharmacists need to establish so as not to develop close ties with the clients. I don’t think I consciously made the observation that it mirrors a movie screen, but I like that image.

SCOPE: On the one hand, the interactions between the pharmacist and the clients are banal, bureaucratic transactions characterized by superficial communication—not unlike going to a bank or a post office. Yet at the same time, these are urgent, crucial, life-and-death exchanges. This paradox must have been part of the ritualistic atmosphere that first fascinated you. One area where this paradox reveals itself is in the use of language in the film, which I don’t think could have been achieved if the film had been scripted. The pharmacy clients often fall back to odd, and at times ill-fitting, clichés to get through the awkward chat with the pharmacist, or with each other. There is often a sense that the clients are attempting a kind of conversation that is somehow impossible for them to properly have. They can’t find the right words at the right moment, they’re talking to the wrong person, who is responding in the wrong way, etc. The painful schism between thought, feeling, and expression is frequently felt inside the pharmacy. And yet some communication is nonetheless taking place, which is at times quite profound.

This is especially apparent in one of my favourite scenes, in which two clients, Jim and Rick, are sitting together trading nuggets of life wisdom. While they discuss Jim’s vague dream of opening a tennis school for children, a woman is sitting beside them extremely high on something. As the men’s conversation becomes movingly reflective and philosophical, the woman becomes increasingly oblivious, utterly lost in her own world. This is simultaneously absurdly humorous, and uncomfortable to witness. I’m curious, how did this scene come about? And more generally, can you comment on the use of language in the film?

BOURGES: The scene you refer to comes from observations the crew and myself had made about Jim, a performer who spent a lot of days in our pharmacy set during production. He and his friends had a great dynamic, and you can see a little bit of it in this scene with his friend Rick. Jim would often monologue about the tennis games he plays with his friends. Because I wanted to include a typical discussion that clients have after their morning dose, I asked him to talk about his last game. I did not expect that he would go as far as exposing his dreams or alluding to religion, but I am very grateful for this generous performance. I am conscious that the presence of the camera may have incited him to express himself to such an extent, but I don’t think this takes anything away from his sincerity at that moment. Similarly, I did not expect the woman sitting next to him to behave the way she did. In fact, you can see her transitioning to this state early in the scene (methadone is not supposed to create this sort of reaction—from what I learned volunteering in the Eastside, this particular conduct could be the result of a state of withdrawal from some street drug).

As for the interactions with the pharmacist, I think it was also important not to facilitate these dialogues with scripted lines, and instead allow these sometimes clumsy moments of conversation to take place. I think what fascinated me was not so much the conflict arising from the different worlds occupied by the pharmacists and the clients, but simply how they negotiate each other’s presence, notably through language. I like that the pharmacy functions as the main bearer of the mise en scène in this way. Or to put it differently, it makes possible the “mise en présence” of these two different worlds. This is what makes them more than places for sociological investigation in my view, but integral sites of cinema.

SCOPE: East Hastings Pharmacy has been shown primarily in documentary festivals or in the documentary sections of festivals. Despite being staged for the camera on a constructed set, this does make a certain amount of sense: it is probably be fair to say that one of the main motivations of your film is to document certain people in a certain place—the atmosphere, the tensions, the power dynamics, the gestures, the language, etc. —rather than to tell a specific story. I suspect that it is this lack of a central narrative that leads programmers to show the film as a documentary—even if it is an explicitly fictional documentary. Can you comment on how you feel about the film being categorized as a documentary?

BOURGES: I have no problem with the film being programmed one way or the other. As you mentioned, a large portion of the film focuses on these documented elements such as gestures, language, [etc.], and more generally the film does depict a certain everydayness, so I can see why a documentary audience might respond more to it. I also agree that where the film seems to depart from the general understanding of fiction is not so much in these strictly documented elements—Italian neorealists and countless fiction filmmakers have also used non-actors, improvisations, etc.—I think it comes from this apparent absence of a constructed narrative thread. By appearing to be exclusively dictated by an ongoing reality lying outside any authorial control, it can easily be interpreted as a record of unguided happenings, as opposed to a pre-established story. Paradoxically, I think the root of this approach draws from very “authorial” films that have influenced me—mainly Bresson’s and Akerman’s—where the sequence of actions seems to be secreted from within, as opposed to constructed.

But the film could just as well be programmed as a fiction in my view, since it tells a story about a fictional character. I have always considered the pharmacist as a character going through a certain narrative arc. I think she is someone who tries to distance and protect herself emotionally, to a point where she may actually be removing herself too much, at the risk of disappearing. This was always very present in my mind while making the film, and I never thought of it as mutually exclusive from a more documented depiction of the pharmacy and its clients.

SCOPE: In Vancouver you worked for the artist Jeff Wall, who has described many of his photographs as “near-documentaries” in that they depict actual things he observed and then later restaged in order to make photographs from them. While your approach in East Hastings Pharmacy has numerous cinematic precedents, some of which you have mentioned, it also seems to take up Wall’s ideas in a particularly interesting way. Did Wall’s work or methods influence your approach?

BOURGES: Absolutely. Even before working for Jeff Wall I would have counted his work as an inspiration. I really connect with the idea of discovering or rediscovering a picture by observing, as performers freely use or inhabit a relatively staged situation. I do think of his work as being very documentary in this way. But to put it simply, I probably would have never considered recreating this pharmacy had I not observed Jeff go through this very process when access to an actual location was not practicable. Something happens in his pictures where the performers and their environment—staged or not—somehow attain an incredible authenticity by simply being in the presence of one another. Of course there is much more to his work than this practical aspect, but I still feel a bit too close at this point to define his influence any further.

SCOPE: Maybe it is somewhat redundant to speak of a film as a “near-documentary.” The vast majority of fiction films are engaged to some degree in the act of documenting, and even the rawest of vérité documentaries involve extensive interventions. So this “near-documentary” quality could perhaps be said to be one of the basic characteristics of most of what we think of as cinema. And yet few films exist as openly in this in-between zone as yours does. Is this an area you are explicitly interested in continuing to explore?

BOURGES: I have to admit it’s not something I consciously set out to explore prior to making this film. I never decided that it should be a documentary or a hybrid, and I generally try not to have fixed principles with regards to the process of making a film. As you noted, all films could be said to be “near-documentaries” in their fabrication, but I still think a distinction can be made with regards to how films embrace life, or reality. It is something you experience as a viewer. For instance, I like the observational aspect of documentaries, but I don’t think observation belongs solely to docs. When I watch a character speak in a Rohmer film, I know she is reciting her lines and following every beat of punctuation laid out in his script, yet the pleasure I get from watching this person speak feels very close to the one I get from an observational film. So perhaps what I want to explore is this open quality of film, this sense that a film can be “in becoming.” I think this is possible to explore even in a very classical approach.

Michael Vass- « Previous

- 1

- 2