Global Discoveries on DVD: Heroines, Heroes, Dogs, Filmmakers

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

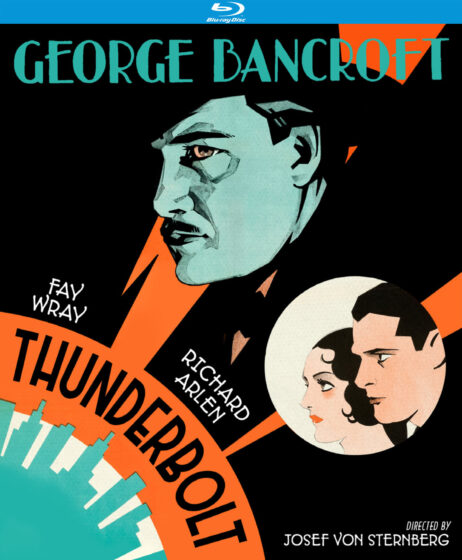

The way the Internet Movie Database tells it, two pairs of writerly brothers worked with Josef von Sternberg on his first talkie, Thunderbolt (1929), recently released on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray (with a knowledgeable audio commentary by Nick Pinkerton that I’ve so far only sampled). Charles and Jules Furthman are both credited for “story,” though Jules, the younger of the two, gets a screen credit for the actual script; Herman J. Mankiewicz is credited for “dialogue,” while his younger brother, Joseph L., is credited for “titles.”

The question is: What titles? The Thunderbolt that I’ve seen and heard many times has none and needs none. Yet according to the American Film Institute’s online catalogue, there was also a silent version of the film—clearly one more missing Sternberg silent, along with The Exquisite Sinner (1926), the Chaplin-produced A Woman of the Sea (1926), The Dragnet (1928), and The Case of Lena Smith (1929), albeit one I’ve never heard mentioned before now.

John Grierson, one of the few people who saw A Woman of the Sea, concluded that “When a director dies, he becomes a photographer”—a verdict that I doubt Stanley Kubrick would have agreed with, although I’m sure that treating Sternberg strictly as a photographer and visual artist has led to the unwarranted critical downgrading of both Thunderbolt, his first sound film, and Anatahan (1955), his last (and a far greater achievement). As an effort to compensate for this neglect, I once even expressed a preference for Thunderbolt over his “official” gangster classic Underworld (1927), after conceding that the former qualifies in some respects as a half-baked remake of the latter. Re-seeing Thunderbolt more recently has cured me of this foolishness, but I think it nevertheless deserves more attention than it’s received, if only for its multifaceted weirdness and its place in Sternberg’s George Bancroft/big-lug period, comprising The Docks of New York and The Dragnet (both 1928) along with Underworld and Thunderbolt (not to mention the Continental versions of this character portrayed by Emil Jannings in The Last Command [1928] and The Blue Angel [1930]). This neglected phase of the director’s work, which provoked the passionate enthusiasm of Jorge Luis Borges during his days as a young film reviewer, could be seen as a tribute to Sternberg’s father (a former soldier and, reputedly, a brutal disciplinarian), just as the six Marlene Dietrich/hefty-lady features that followed comprise a tribute to his no-less-imposing mother: Bancroft’s cheerfully triumphant march to his execution at the end of Thunderbolt is neatly echoed by Dietrich’s proud exit as a pseudonymous Mata Hari greeting the firing squad at the end of Dishonored (1931).

In his well-written but abrasively score-settling memoir Fun in a Chinese Laundry, Sternberg (who alludes in passing to Joseph L. Mankiewicz writing some of his titles) complains that even though Thunderbolt was well-received, no one acknowledged his efforts to use sound “to counterpoint or compensate the image” apart from his fellow director Ludwig Berger, who sent him a congratulatory telegram to that effect. Given all the eccentric experimentation with sound in Thunderbolt, much of it devoted to play between selective sounds and selective silences, it’s very hard to imagine what the silent version could have been like. (Someone with access to the Paramount files should undertake a research project about this.) A lot of the weirdness of the surviving version involves animals (a cat and a dog), plus a black nightclub called Black Cat that dominates the film’s first half, and a set of cells for condemned prisoners awaiting execution that dominates the second half. Both halves feature a lot of on-location music, which becomes hyperbolic in the prison section, where entire concerts of spirituals with piano accompaniment, a barbershop-style quartet of singers, and a few snatches of a quintet composed of prisoners performing chamber music are heard successively, although the other prisoners tend to ignore and talk over these frequent outbursts. No less implausibly, the comically hysterical warden (Tully Marshall) lets Bancroft’s Thunderbolt out of his confinement long enough to disarm another prisoner, then rewards him by letting him keep his dog in his cell.

Three years before Thunderbolt, Sternberg won the assignment of directing Underworld, his first feature at Paramount, by reshooting roughly half of Frank Lloyd’s Children of Divorce (1927) over a three-day marathon with reassembled sets under a tent. The results, now restored and viewable on Blu-ray and DVD from Flicker Alley with a nice orchestral score, are mostly seamless (apart from a track up to Clara Bow’s eyes, one of Sternberg’s many steals from Stroheim and a dry run for his more memorable track up to Dietrich’s eyes in Dishonored), and generally watchable thanks to Bow and one of her co-stars, Gary Cooper (who hadn’t yet learned how to coast on his sheer screen presence rather than rely on his acting chops). Bow’s forte, like Marilyn Monroe’s and Maggie Cheung’s, is basically comedy, but her facial expressions are so animated (even in a glum drama about upper-crust partygoers from broken homes trying to behave decently) that she all but turns Cooper into a Bressonian “model” in their scenes together.

The most valuable aspect of Lizzie Borden’s non-erotic but by no means anti-erotic Working Girls (1985) is the film’s treatment of New York prostitutes as subjective heroines/protagonists/characters rather than objectified and eroticized victims/symbols/images—an aspect which is enhanced further by the new Criterion edition’s inclusion of an extra (one of many) in which four real-life contemporary sex workers (including one trans) of different generations discuss and politely critique the film, vouching for its accuracy and authenticity even as they note how it short-changes issues pertaining to prostitution’s illegality and how this affects both the work and the workers. (I also particularly value the inclusion of a recent and very smart dialogue between Borden and Bette Gordon, which concerns both Working Girls and the latter filmmaker’s 1983 Variety.)

The most pressing question raised by Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s 2020 documentary Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation (available on a DVD from Kino Lorber) is: How can a conversation between Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams possibly be “intimate” if we’re all being invited to watch and listen to it? But the ambiguous crossovers between public and private that characterized the gossipy careers of both of these troubled writers is so fully on display here that the question eventually answers itself. Even more welcome is how much mileage Vreeland wrests out of her archival TV clips and the voice recordings made with actors playing the two principals, even when it comes to following the bumpy paths and detours of their friendship.

What seemed sad to me about Carole Lombard’s supposedly assertive and plucky characters in the three mid-’30s comedies of Kino Lorber’s Carole Lombard Collection II—Hands Across the Table (Mitchell Leisen, 1935), Love Before Breakfast (Walter Lang, 1936), and The Princess Comes Across (William K. Howard, 1936)—is how quickly they wind up succumbing to patriarchal dictates and related conventions, including the alleged upper-crust charms of Fred MacMurray and his multiple entitlements in the first and third of these pictures, as well as those of Preston Foster and Cesar Romero in Love Before Breakfast.

I still enjoyed the second and third of these, for the deceptively and sarcastically titled Love Before Breakfast’s critique of Lombard’s wealthy character’s neurotic, obsessive pretense of being independent, and for her working-class character’s mannered attempt to impersonate Swedish royalty in The Princess Comes Across (whose title seems to refer back to director Howard’s 1931 Transatlantic, a particular favourite of mine). But Hands, in which Lombard plays a gold-digging manicurist opposite Fred MacMurray’s spoiled tycoon hero, struck me as phony for many of the same reasons that Billy Wilder’s use of MacMurray as the villain in The Apartment (1960) did a quarter of a century later. Not only does MacMurray’s hero in Hands prefigure the same aura of bored privilege as his villain in The Apartment, but his forced eccentricity in the Leisen film (e.g., a game of indoor hopscotch) anticipates the bricolage of Jack Lemmon’s straining spaghetti with a tennis racquet in the Wilder Oscar winner, the cutesy counterpoint to that film’s pseudo-toughness (as summed up by its unduly famous closing line: “Shut up and deal”).

For sheer Wilderian cutesiness, however, nothing comes close to the fighting, barking, and cuddling of a male runt belonging to phonograph salesman Bing Crosby and a royal bitch belonging to Austrian countess Joan Fontaine—which, naturally, predicts the developing relationship of their owners—in the Austrian émigré’s mock-up of 1901 Vienna, The Emperor Waltz (1948), Wilder’s first encounter with Technicolor and his first ham-fisted salute to Lubitsch, out on another Kino Lorber Blu-ray. This was made the same year as another Crosby vehicle, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, a not-dissimilar period musical in which Crosby plays a relaxed, all-American yahoo who knows how to scat while riding roughshod over stiff, stuck-up Europeans. The bitter class resentment of The Apartment is presented far more optimistically here, and Wilder’s venom seems trained mostly on Sigmund Freud, specifically when he wheels out Sig Ruman as a psychiatrist for the royal bitch—the canine, that is. (According to Wilder biographer Maurice Zolotow, Wilder’s Freud animus dated from the time when the esteemed doctor once refused an interview with Wilder, who was at the time working as a reporter, and ejected him from his premises.)

Cecil B. DeMille is typically either celebrated or ridiculed for the simplicity of his period blockbusters, but what attracts me to his 1930s work is most often his complexity, especially in his contemporary pictures: I’ve already written in this column (and elsewhere) about the ideological ambiguities of Dynamite (1930), Madame Satan (1930), and This Day and Age (1933). The only exception to this tendency may be the still-enjoyable 1934 Cleopatra, available on a Universal Blu-ray, which is arguably more entertaining than the 1963 Joseph L. Mankiewicz epic. All things considered, Claudette Colbert is a lot funnier as the Queen of the Nile than is Elizabeth Taylor, who is too beautiful to be funny; it’s also amusing to see her follow up her lusty turn here by playing a bluenose who needs to be liberated from her uptightness in DeMille’s Four Frightened People, made the same year as Cleopatra.

The latest batch of DeMille Blu-rays from Kino Lorber includes both Four Frightened People and Union Pacific (1939), good examples respectively of his present-day complexities and ambiguities and diverse period simplicities. Not that I mean to downgrade the virtues of simplicity and big-scale spectacle: Union Pacific, an energetic paean to colonial expansion which won the very first Palme d’Or at Cannes and also features a couple of Oscar-winning train wrecks (which De Mille later tried to top in The Greatest Show on Earth), is a very engaging romp as long as one can overlook its repulsive way of depicting Native Americans. (It’s also spiked with some jazzy star turns, including Barbara Stanwyck sporting a thick Irish accent and Akim Tamiroff as a salty Mexican bodyguard.)

Outfitted by Kino Lorber with yet another Nick Pinkerton audio commentary, Four Frightened People—about the diverse survivors of a plane crash who are forced to trek through a South American jungle to safety—automatically becomes cross-referenced and (more often) confused in my mind with John Farrow’s similar Five Came Back (1939), which is available only on a pricey DVD that I don’t have. I saw the latter on my laptop for the first time (thanks to the endlessly bountiful ok.ru) just after attending a Farrow sidebar at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in late July, which consisted of an informative new Australian documentary (Claude Gonzalez and Frans Vandenburg’s John Farrow: Hollywood’s Man in the Shadows) and Farrow’s very weird Alias Nick Beal (1949), a Faustian noir submerged in fog (or dry ice) that is available on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray. In fact, while going on a minor Farrow binge inspired by that Bologna sidebar, I also discovered the nightmarish Where Danger Lives (1950), which Imogen Sara Smith aptly describes in the Farrow doc as a fever dream (for much of its running time, Robert Mitchum’s muddled protagonist is staggering around in unheroic, post-concussion mode). It’s currently available on a Warner Archive DVD, paired with John Berry’s equally mesmerizing and notably creepy noir Tension (1949).

DeMille and Farrow aren’t really comparable, apart from the fact that they both worked in many different genres, were both libertarian conservatives, and were also, sometimes, two-faced hypocrites in their sexual habits (thus accounting for certain aspects of their ambiguities and complexities regarding both sex and class). Still, the offbeat casting of Colbert as the sheltered, repressed survivor in Four Frightened People somehow rhymes with the equally offbeat, non-comic casting of Lucille Ball as a prostitute in Five Came Back, even though the characters are almost antithetical.

Thanks to Mank and its exceptionally dubious biographical premises (which, owing to studio clout, have become common currency), Herman J. Mankiewicz now has the sort of renewed cultural prestige that only big-corporation money can buy, including a program at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Yet grateful as I am for any excuse to show Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast’s 1930 Laughter (commercially unavailable) and Edward F. Cline’s 1932 Million Dollar Legs (available on a Universal DVD)—even though the elder Mankiewicz brother received no screen credit on either picture—I’d much rather see tributes paid to the sophisticated but far less heralded literary talents of John Collier (especially for his work on Sylvia Scarlett [1935] and The Story of Three Loves [1953]) and the prolific Donald Ogden Stewart, whose own onscreen credits include Laughter, over a half-dozen Cukor films, and movies for Duvivier, Lubitsch, McCarey, and Walsh.

If you aren’t happy with the milky textures of Tarnished Lady (1931)—Cukor’s first solo feature (as well as Tallulah Bankhead’s first talkie), adapted by Stewart from his own short story—as the film appears on YouTube and ok.ru, a restoration of this picture would make an excellent addition to a Donald Ogden Stewart box set, an impossibility that I still like to dream about. (That dream, however, would discreetly omit both of Stewart’s preachy, moralistic adaptations for Cukor built around absent, eponymous villains: the dreadful 1942 Keeper of the Flame and the slightly less objectionable 1949 Edward, My Son.) Tarnished Lady is a fascinating relic that illustrates Raymond Durgnat’s maxim that some movies are more interesting simply because they’re dated (rather than “contemporary” or “timeless”). Bankhead’s brazen and unabashedly bitchy intelligence (“I’m as pure as the driven slush,” she once aptly remarked); Cukor’s special feeling for how some female stars like to look at themselves (for elaboration, see “Cukor and Sensuality” at jonathanrosenbaum.net); Larry Williams’ scintillating cinematography of New York sets and locations, including a shimmering moonlit beach; diverse, pre-Code Depression protocols about marrying for money and then regretting it (which also dominate Laughter)—these are only a few of my favourite things that most DVD companies couldn’t care less about.

Bologna’s main Hollywood retrospective this year was devoted to the mid-career work of George Stevens, much of which I find complacently conformist and sluggish. But it also introduced me to the totally neglected and highly unorthodox Something to Live For (1952), an offbeat, Manhattan-set drama starring Ray Milland and Joan Fontaine as, respectively, an advertising executive and family man enrolled in AA and the boozing, solitary stage actress he counsels, who eventually become adulterous, alcoholic lovers who can’t decide whether to revise or capitulate to their drinking or non-drinking habits (a dilemma reflected in the film’s bizarre crosscutting patterns). The original screenplay is by Dwight Taylor (whose credits include three early Astaire-Rogers pictures), son of stage actress Laurette Taylor, who was inspired in part by memories of his mother. I’m told that a restoration of this Paramount feature is being planned at Universal, but you can already find unrestored and affordable DVDs on the internet.

Is French cinephilia alive or dead? You could arrive at opposite conclusions by reading or thumbing through the recent memoirs of Luc Moullet and Noël Burch, whose respective titles translate into English as Memoirs of a Slippery Bar of Soap and Memoirs of a Defector from Cinephilia. Moullet’s Memoirs offer enlightening and honest details about the internal politics of Cahiers du Cinéma, the complex procedures involved in financing French films, and the author’s separate careers as critic and writer-director-producer-actor, plus many funny puns and jokes; Burch’s less jokey recollections focus not so much on his work as a writer or filmmaker as on his sexual relationships, combined with his proud scorecard as an alleged radical feminist and anti-bourgeois elitist-turned-populist who became masochistically involved, sometimes clandestinely and/or adulterously, with diverse women connected to film. This undoubtedly helps to explain why we have a Moullet box set, including one with English subtitles (six features on four DVDs released by Facets Video, $53 from Amazon), but will probably never have a Burch one.

During my week in Paris after Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was pained to discover that the weekly alternative L’Officiel Spectacles had seemingly vanished, sharing the same sad fate of Pariscope (with its weekly lists of movie-theatre offerings), which had closed down prior to my last visit. Though I was later relieved to find out that L’Officiel Spectacles was only on summer break, it still seemed a sign that, in many respects, French cinephilia ain’t what it used to be. Even so, it still trumps American cinephilia when it comes to some appreciations of Hollywood—e.g., the continuing releases of letterboxed Westerns on DVD by Sidonis Calysta (sidoniscalysta.com) in both their original versions (with, alas, unremovable French subtitles) and French-dubbed editions, for ten euros apiece (though that price gets steeper if you have to worry about paying postage to French Amazon or FNAC). This series has been expanding for years, with many of the releases including thoughtful, unsubtitled intros delivered by the late Bertrand Tavernier. My latest purchase—a pretty good Dana Andrews Western-cum-murder mystery (3 heures pour tuer/3 Hours to Kill, Alfred L. Werker, 1954) that I recall having enjoyed at age 11—is introduced by Patrick Brion, who also offers a separate spiel about Andrews.

Another French digital release worth citing is a gorgeously designed dual-format edition of Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames (2017) from Potemkine Films (25 euros from French Amazon), which comes in the form of a small, compact, hardcover book with no less than 48 full-page frame enlargements, two from each sequence. (The texts are much more frugal: one essay in French by André Habib, plus a few short Kiarostami poems in French and Farsi.) The discs include a short making-of documentary and an hour-long dialogue between critic Godfrey Cheshire and Kiarostami’s son and producer Ahmad at Lincoln Center from 2018.

Reviewing Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep (1996) almost a quarter of a century ago, I posited the notion that the film’s narrative actually had an “unconscious” that was manifested in two mysterious and otherwise inexplicable sequences that suggested alternate versions of the remake of Louis Feuillade’s Les vampires (1915) being made by director René Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud). One, in colour, shows Maggie Cheung, in her latex Irma Vep suit, stealing jewels from an unsuspecting, naked hotel guest (Arsinée Khanjian) and then tossing them off a rain-soaked rooftop; the other, which comprises the final sequence of Assayas’ film, is an experimental fragment in graphically scratched-up black and white, the only edited portion of the scuttled remake that Vidal completes before suffering a nervous breakdown (a plot detail that was likely inspired by Jacques Rivette’s collapse while working with Leslie Caron and Albert Finney on a never-completed feature). The first of these sequences can perhaps be read as Cheung’s dream, the latter as Vidal’s, but these identifications remain so uncertain that one could just as easily call them the dreams of Irma Vep itself.

It’s just my luck that this year has seen the re-releases of three favourite films of mine that can each be said to have a throbbing, hyperactive unconscious, creating dreams that are at once vivid and somewhat out of reach: from Criterion, the aforementioned Irma Vep and Rivette’s 1974 Celine and Julie Go Boating (whose unconscious is manifested inside a mysterious haunted house where the same drama is repeated endlessly, like a film in a movie theatre); and, from Film Movement, a Blu-ray restoration of my favourite Hong Kong art movie, Stanley Kwan’s Center Stage (a.k.a. Actress, 1991), a masterful meditation on silent star Ruan Lingyu, for which Maggie Cheung won the Best Actor prize at Berlin (the first time a Chinese actor received a prize at a major European festival). I should further note that the latter release is the full, 154-minute version of the film, which I was privileged to see at its world premiere at the Golden Horse Awards in Taipei in 1991; those who’ve seen only the truncated version of this masterpiece won’t know what I’m talking about.

I would submit that the unconscious of Kwan’s film is, paradoxically, the real yet elusive historical past that the film tries to evoke without ever being able to capture—a past so ungraspable and labyrinthine that it ultimately overwhelms everything we see and hear about Ruan Lingyu, whom Kwan here gives the worshipful Cukor treatment. Having written recently at much greater length about this film for Found Footage #7, which came out last spring, I will only suggest here that during these Plague Years, when the coronavirus panic gives us all more pungent and more protracted dreams and dream lives, the value of these three masterworks and the infinite reaches of their subterranean chambers and undercurrents is only enhanced.

Jonathan Rosenbaum