Global Discoveries on DVD: Deliveries of Smart Dialogue by Dieterle and Others

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Apart from their impressive craft, the most striking common element I find in the early American talkies and ’40s fantasies by William Dieterle that I’ve seen is how literary they are. This adjective often has negative connotations in this North American neck of the woods, apparently because “literary” and “cinematic” are supposed to be antithetical—though clearly not for Orson Welles, nor for Godard, who devoted his first piece of film criticism to defending Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and virtually ended his 2 x 50 Years of French Cinema (1995) with his appreciative survey of literary texts that (for him) were an essential part of cinema, “from Diderot to Daney.”

It’s surely silly to fault a screenplay because its dialogue is witty, smart, and well-written, and this is part of what impresses me about Dieterle’s The Last Flight and Lawyer Man (1931), Man Wanted and Jewel Robbery (1932), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), Blockade (1938), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), All That Money Can Buy (1941), and Portrait of Jennie (1948), among other examples from the director’s filmography. I don’t mean to suggest that Dieterle wrote any of these movies, as he wasn’t a writer like Godard or Mankiewicz or Welles; only that he knew how to make their literary virtues shine and shimmer. (The fact that some early talkies are so literate and literary in both their language and their overall orientation can obviously be traced to the influx of talented playwrights and novelists from the east coast that came with sound. “With talk came the Jew,” Frieda Grafe quotes the younger Mankiewicz saying, in her book about his The Ghost and Mrs. Muir [1947], but the goyim also seem pretty well-represented in terms of articulate screenwriters during this period.)

While it’s worth adding that Dieterle’s first (silent) film in Germany was an adaptation of Tolstoy, and that a relatively relaxed way of handling countries other than the US marks everything from The Last Flight to the 1954 Elephant Walk (if my memory of the latter is to be trusted), as a jack of all trades who took on all sorts of assignments, including several he reportedly didn’t like, Dieterle is probably closer to someone like Mervyn LeRoy (a favourite of Samuel Fuller) than a more narrowly self-defined auteur like Lubitsch, or even a more ambidextrous one such as Jacques Tourneur. I don’t know whether he deserves to be considered an auteur at all, but unless you’re doctrinaire on such matters, this shouldn’t interfere with you searching out his enjoyable features.

The Last Flight, Dieterle’s first English-language and first Hollywood feature (available on DVD in the Warner Archive Collection), shows a remarkably confident grasp of American dialogue and idioms. Based on John Monk Saunders’ novel Single Lady, it’s a skilfully made Lost Generation effort that’s more F. Scott Fitzgerald than Ernest Hemingway, even though a (Portuguese) bullfight figures in the plot. In 1919, four physically and/or spiritually wounded American war pilots (played by Richard Barthelmess, Johnny Mack Brown, David Manners, and soon-to-be director Elliott Nugent) booze it up in Paris and Lisbon with a wealthy ingenue (Helen Chandler) in tow in order to avoid returning home, exuding the sort of sad and hopeless gaiety one associates with postwar Fitzgerald. (Saunders, who co-scripted the adaptation of his novel, also furnished the stories for the equally moody The Docks of New York [1928] by Sternberg and Hawks’ The Dawn Patrol [1930], which also starred Barthelmess.)

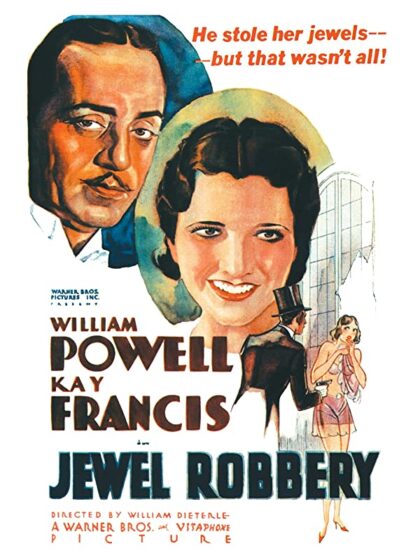

I’m less keen about Lawyer Man, a populist fable co-starring William Powell and Joan Blondell (available on DVD from Amazon for an exorbitant price, and on Amazon Prime for a reasonable price). Powell seems less comfortable than usual as a downtown lawyer who decides to become crooked after moving uptown, until he belatedly sees the error of his ways. He’s far better as a suave gentleman thief in Jewel Robbery (available at comparable prices on Amazon), robbing and wooing Kay Francis, but at least his wishy-washy lawyer delivers his brittle dialogue with the same percussiveness.

By contrast, Francis’ fine performance in Jewel Robbery is equalled by her splendid turn in Man Wanted (available for rental or purchase on Amazon Prime), a classy and brassy comedy that co-stars Una Merkel and a relatively thin Andy Devine. A likable and interesting alternative to the same year’s Trouble in Paradise (see below), Man Wanted has Francis playing far more of a feminist role model than the role furnished for her by Lubitsch and Trouble screenwriter Samson Raphaelson. Playing the hard-working editor of a big magazine, Francis hires a male secretary (The Last Flight’s Manners) whom she falls for just as she does Herbert Marshall in Trouble, but in this movie the flirtation is complicated by the fact that she also has a wealthy, philandering husband (Kenneth Thomson), whom she affectionately tolerates and even seems to like.

I’ve written about the enticingly subversive Jewel Robbery as an alternative to Lubitsch elsewhere. A masterpiece in its own right which sparked my interest in exploring the less fashionable Dieterle, Jewel Robbery is my prime Dieterle pick so far, although his subsequent and better-known literary fantasies—A Midsummer Night’s Dream, All That Money Can Buy, and Portrait of Jennie—are also impressive. So too is Blockade (available on pricey DVDs, or for cheaper fees on Amazon Prime), the only decent Hollywood movie about the Spanish Civil War that I’m aware of. Thom Andersen and Noël Burch, in their book Les communistes de Hollywood (the forerunner of their 1996 documentary Red Hollywood), describe the film as “the fruit of an exemplary collaboration between the liberal independent producer Walter Wanger, the anti-fascist German immigrant Wilhelm Dieterle, and the communist screenwriter John Howard Lawson” (my translation), though according to IMDb, James M. Cain and Clifford Odets also made contributions to the script. Whatever its sources, Blockade is made with heart and passion as well as some thought, which makes me wonder why it’s been so ignored; maybe it’s the absence of the Lubitsch touch, the Wilder wiggle, Hawks’ fatalism, or the Ford-spangled banner. Henry Fonda is powerful as the second lead (after Madeleine Carroll), but his performance as a farmer-turned-partisan is less rhetorical and more probing and exploratory, even questioning, than his better-known turns for Ford, hence more hit-or-miss but also more exciting in spots.

I should add that I still haven’t seen Dieterle’s most famous works, his industry-approved biopics starring Paul Muni (The Story of Louis Pasteur, 1935; The Life of Emile Zola, 1937; Juarez, 1939) and Edward G. Robinson (Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet and A Dispatch from Reuters, both 1940). But whenever I do get around to them, I’ll be interested to see if his worldliness and literary taste give a bit more flavour to this typically staid genre.

***

My favourites of the four features in Flicker Alley’s two-disc Blu-ray package In the Shadow of Hollywood: Highlights from Poverty Row are the first and last, for quite different reasons. Call it Murder, a.k.a. Midnight (Chester Erskine, 1934), a very suspenseful crime thriller, may have an all-too predictable denouement (a minus) as well as Humphrey Bogart (a plus), but the working-out of its visual details is an object lesson in how a play (Paul and Claire Sifton’s Midnight) can be adapted cinematically for maximal impact. The chief virtues here are a fancy, inventive mise en scène (including many lateral movements of the camera and characters, as well as a concentration on the expressive movements of hands and feet) and relentless crosscutting between a woman awaiting execution and the jury foreman who helped to convict her.

The set’s closer, on the other hand, The Crime of Dr. Crespi (John H. Auer, 1935), is gripping and memorable less for its able direction—which alludes to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Vampyr (1932), but only in a Paul Schrader-esque copycat fashion that rules out invention—than for a typically volcanic and mesmerizing turn by Erich von Stroheim as the villainous title character. Simply watching him toss off a drink in the same stiff-necked manner as his very different character in Renoir’s La grande illusion (1937) will do a couple years later is all it takes for me to forgive the awkward horror-story contrivances in the plot, loosely inspired by Poe’s “The Premature Burial.”

Another reason for getting this set is these films’ shared, Depression-fuelled vision of how law and order serves the already privileged over those without money, which is the explicitly spelled-out theme of Call it Murder (as suggested by this title) and a constant undertow and subtext to the action in both Back Page (Anton Lorenze, 1934) and Woman in the Dark (Phil Rosen, 1934), at least before their final, mopping-up resolutions. In spite of a winning lead performance by Peggy Shannon as an energetic newshound who takes charge of a small-town paper and mainly opts for her whistle-blowing work over romance, Back Page has so many silly plot contrivances that I originally thought that this was a stupid movie made for stupid people. But while the annoyingly mannerist overacting by one of Shannon’s beaus, as well as the laboured gawkiness of Sterling Holloway, certainly don’t help in this regard, the narrative’s drive ultimately matches the heroine’s.

Woman in the Dark, adapted from a Dashiell Hammett story, has more familiar faces (including Fay Wray), but accepting Ralph Bellamy as a convict with a deadly temper and a killer punch and Melvyn Douglas as a wealthy, drunken mobster (even one who is first seen in a tux) wasn’t easy for me to swallow. I eventually concluded that the fault was either the filmmakers’ for miscasting them, or mine, because the actors were cast in these parts before they developed their more typecast personae—meaning that, as with my disbelief at the sight of a slender Andy Devine, my viewpoint was slanted by my acquaintance with their later work.

***

After writing all the above, another Dieterle gem arrived in the mail—The Accused (1949), from Kino Lorber—a thriller that’s almost as suspenseful as Call it Murder with a plot that’s almost as contrived, but this time put together with sharp psychological notations and nuances rather than social ones. (I also love the way this film concludes with a deft and witty ellipsis that manages to sidestep the Hays Code.) Like the other Dieterle movies cited above, it has well-written dialogue (by Ketti Frings and Jonathan Latimer, from a novel by June Trunsdell called both Be Still, My Love and Strange Deception) and, once again, I think that the dialogue shines all the more thanks to Dieterle’s direction of actors. The film co-stars two of my less-than-favourite actors, Loretta Young (as a professor of psychology who kills a student who tried to rape her and then doesn’t report the murder) and Robert Cummings (as the student’s guardian, who falls in love with her), and both of them are so good in their parts that I wind up suspecting that my previous disaffection for them may have been for the sort of characters they often wound up playing. (One of my favourite character actors, Sam Jaffe, is also cast in a smaller part, and he’s good, too.)

***

So much for the potential hazards and rewards that I find in watching stuff from the ’30s and ’40s. Leaping ahead to the ’80s and ’90s, I’d like to both applaud Second Run Features’ release of Ann Turner’s first feature, Celia, and hope that it sells well enough to persuade this label to release her third, the 1994 Dallas Doll (the latter of which was formerly available in VHS only in the UK). My contemporary capsule review of the former for the Chicago Reader is reprinted below:

“The first feature (1988) of the quirky, original, and subversive Australian writer-director Ann Turner, whose 1994 Dallas Doll was one of the best and weirdest independent efforts of its year, Celia isn’t quite as good, but it tells a fascinating and disquieting story, set in 1957 Melbourne, about the effects of anticommunism and a rabbit plague on the nine-year-old girl of the title. Her grandmother, who dies just before the film begins, had been a member of the Australian Communist Party, as are the parents of the children who live next door, with whom Celia forms a blood pact. Her father and uncle’s intolerance of communists is elaborately cross-referenced with local fears about proliferating rabbits, which have dire consequences for Celia when she acquires a pet bunny; her forms of rebellion escalate to voodoo rites and ultimately murder. The storytelling isn’t as streamlined as one might wish, but the performance of Rebecca Smart as Celia and Turner’s passionate viewpoint make this both arresting and distinctive.”

And here is what I had to say about Dallas Doll, also from the Reader:

“This 1994 feature is much too goofy to qualify as an absolute success, but it’s so unpredictable, irreverent, and provocative that you may not care. Australian writer-director Ann Turner has a lot on her mind, and it’s unlikely you’ll be able to plot out many of her quirky moves in advance. Imagine Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (with Sandra Bernhard in the Terence Stamp part, seducing most of a bourgeois Australian family and enough other country-club notables to wind up as mayor) crossed with Repo Man and you’ll get some notion of the cascading audacity. This is a satire about foreign invasion in which America (in the form of Bernhard, a spiritual “golf guru”), then Japan, and finally extraterrestrials in a spaceship all turn up to claim the land down under as their own. Along the way Turner gives us delightfully incoherent dream sequences, bouts of strip miniature golf, some hilarious lampooning of the new-age mentality, and one of my favorite performances by a dog. Incidentally, Bernhard despises this movie and trashes it whenever she gets a chance, but I liked it as well as or better than many of her own routines.”

***

Satyajit Ray, another film master who was literary in the best sense, mainly had to depend on amateur scholars of Indian culture, history, and literature to acquire his international reputation. Foremost among the American reviewers who praised him was Pauline Kael, who did a very persuasive job. Back in the early ’60s—before she quit servicing the Bay Area arthouse audience and fighting the good fight against New York provinciality for the sake of moving east and becoming the house intellectual of anti-intellectual cinephiles, thereby earning her national renown—she was my principal guide into Ray’s greatness, especially in her lengthy defence of Devi (1960). Kael even maintained that, “if there had been no [Apu] trilogy, I would say of Devi, ‘This is the greatest Indian film ever made,’” as if she had somehow managed to see all the other contenders. Even so, this was more than enough to get me to see the film, and I was certainly glad that I went, even as the film’s intricacies proved too formidable for Kael’s amateurism to fully comprehend.

Set in rural Bengal in 1860, the film’s plot concerns a teenage bride named Doyamoyee (Sharmila Tagore) who, while her more Westernized husband (Soumitra Chatterjee) is away in Calcutta, is suddenly declared an incarnation of the goddess Kali by her wealthy and devout father-in-law (Chhabi Biswas) on the basis of a dream he has just had about her. Due to what was interpreted by some as an attack on Hinduism, the film was sufficiently controversial in India to have been initially banned from export, delaying foreign releases until it was cleared by Nehru. When it did play overseas, it was met with other misperceptions, even from its defenders. Commenting on how Western viewers’ unfamiliarity with Hindu customs and traditions skewed their readings of the film, SatyajitRay.org notes that “even Pauline Kael, who greatly admired [Devi], wrongly read ‘startling Freudian undertones’ [into the] film,” adding that she was probably referring to a scene of “Doyamoyee massaging her father-in-law’s feet [which,] in fact, is a mark of respect towards elders, usually parents and parents-in-law.”

In fairness to Kael, whose amateurism in the realm of Indian culture is one which I share, I wonder if what she meant by “Freudian” was “erotic.” Nevertheless, 60 years on I’m far better served by the thoughtful and informative materials accompanying Criterion’s 4K digital restoration of Devi: an excellent prose essay by Devika Girish, and a no-less-illuminating audiovisual essay by Meheli Sen (both American East Coasters, as it happens), as well as 2013 interviews with actors Tagore and Chatterjee. I’d like to think that more North Americans will enjoy Devi in 2021-22 than their counterparts did (or could) in the early ’60s as the result of this well-stocked release, but I still miss Kael’s less informed but angrier and more unreasoning passion for the film. To serve today’s film culture, both amateur enthusiasm and better informed (if somewhat drier) academic professionalism are needed.

Jonathan Rosenbaum