Global Discoveries on DVD: Auteurist Updates

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Paul Verhoeven gives exceptionally good audio commentary, especially on the Kino Lorber Blu-ray of Spetters (1980), a powerful feature about teenage motocross racers in a small Dutch town that I’ve just seen for the first time. Speaking in English, Verhoeven tells us a good deal about Dutch culture and life at the time his film was made; his own ideological motivations (such as his desire to depict accurately the behaviour of his young working-class characters) and personal contributions to the script (especially, but not exclusively, those relating to his early involvement with Pentecostal Christianity); his literary influences (in particular, the role played by Céline in conceptualizing the final sequence) and his strategies as a director (including the use of his own dog, who also turns up in The Fourth Man [1983]); his relations with his producer, his locations in and around Rotterdam, his cast and how he directed them; the differences between shooting in Holland and shooting in the US; the filming of stunts; his tricky dealings with Dutch government representatives to avoid censorship (which involved lying and subterfuge); the film’s disastrous initial critical reception, which had a lot to do with Verhoeven subsequently moving to Hollywood; and a great deal more. (There’s even a lot of detail about how he filmed erections.) He doesn’t ever get around to explaining the meaning of the film’s title (which, according to Google Translate, is the Dutch word for “splashes”), but given the wealth of what he has to offer, it’s an excusable omission. In short, Verhoeven offers just about everything one might want from an audio commentary, including an acute critical appreciation of what he accomplished, which he offers without vanity or special pleading—and which is reason enough for sitting through all of this movie twice.

***

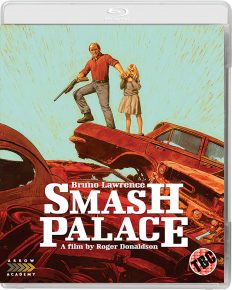

Regarding another early ’80s film about racers and their fucked-up lives and relationships, Roger Donaldson’s 1981 Smash Palace (out on a peachy Blu-ray from Arrow Academy), I’m afraid it’s crow-eating time. In my last column, covering Donaldson’s 1977 theatrical debut Sleeping Dogs (another Arrow Academy Blu-ray), I confidently and foolishly concluded that “whether he’s working with good material or unredeemable treacle, Donaldson registers as a technician and metteur en scène, not an auteur.” But that was before I had my first look at Smash Palace, which is clearly working with good material that is Donaldson’s own, including first-rate actors that he cast and directed himself, and is every inch an auteur film. Maybe it’s his only one, or maybe there are others I still haven’t seen, but this time I won’t presume to draw any hasty conclusions. The 53-minute documentary about the film’s inception, its precarious state financing (as a New Zealand feature), its production and reception, as well as the audio commentary by Donaldson and stunt driver Steve Millen (which I’ve only sampled), makes it plain that this was a personal project throughout.

***

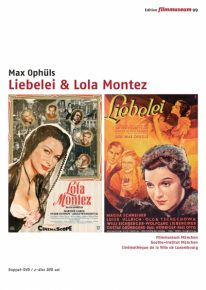

I’ve already recorded my preference in this column for Stefan Drössler’s restoration of the German-language version of Max Ophüls’ Lola Montès (1955) over the French version released by Criterion, mainly because of the German version’s gorgeous colour, but until recently I despaired of this ever becoming available anywhere commercially, due to Ophüls’ son Marcel effectively (and, so far as I can tell, irrationally) outlawing it. So the very welcome release of this version by the Munich Filmmuseum, on a double bill (and in a two-disc package) with Ophüls’ 1933 Arthur Schnitzler adaptation Liebelei, is a major event worth celebrating. There are also many significant bonuses here, most notably an excellent feature-length documentary (Martina Müller’s 1990 Max Ophüls—Den schönen guten Waren, the latter phrase of which is rendered by Google Translate as “the beautiful good goods”) and, among the CD-ROM extras, a 1956 German radio play written by Ophüls in which he also appears, directed by Ulrich Lauterbach. My only (minor) complaint is that the accompanying 20-page booklet, identified as “bilingual,” in fact employs English only to explain on the penultimate page that “Drehbuch und Regie” means “Directed and Written by,” and a few other basic terms of that sort. But the three preceding articles by Müller and the one by Drössler (the latter perhaps explaining how he managed to get Ophüls fils to change his mind) are exclusively in German. However, I hasten to add that, far more importantly, Liebelei, Lola Montès, and the Martina documentary are all provided with optional English subtitles.

***

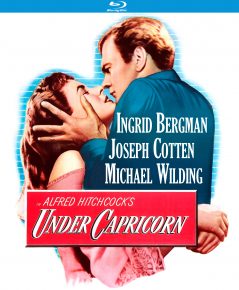

Back in 1985, writing in the Chicago Reader, Dave Kehr called Under Capricorn (1949) “[e]asily one of Alfred Hitchcock’s half-dozen greatest films.” Reseeing this strange, stage-like Gothic Australian neo-Western (which sees Hitchcock continuing the long-take experiments he began the previous year with Rope) on Kino Lorber’s nifty new Blu-ray, I wouldn’t go quite as far as Kehr, even though the film probably has Hitchcock’s most beautiful single lap dissolve: from a rain-soaked window during a thunderstorm to Ingrid Bergman’s tear-streaked face in close-up, rendered in ravishing Technicolor (a shot amply appreciated by Mark Rappaport in his definitive essay about the film, found in both Trafic #41 and The Hitchcock Annual Anthology). Yet I think this non-thriller is worth far more attention than it usually gets, even if I must categorically reject the judgment of the Young Turks of the mid-’50s Cahiers du Cinéma who voted it Hitchcock’s greatest (at the same time that they picked Mr. Arkadin [1955] as Welles’ greatest, no doubt for polemical reasons). And without necessarily declaring it “better” than either of Hitchcock’s two preceding films with Bergman, Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946), I have to admit that in some ways I prefer it to both of them for its clear personal and emotional investments, which make me regard it as a kind of melancholy way station between Rebecca (1940) and Marnie (1964).

What makes this Blu-ray especially valuable to me (not counting Kat Ellinger’s audio commentary, which I haven’t yet sampled) is a well-recorded snatch of Hitchcock talking about the film to Truffaut (and Helen Scott adeptly interpreting for both of them), castigating himself mercilessly for all the wrong decisions he feels he made on the film and for his vanity in going gaga over the prestige of returning to England with the biggest star of the day to shoot a plush period blockbuster. There’s also a Robert Fischer interview with Claude Chabrol done for German TV (in which one has to navigate between Chabrol’s French, Fischer’s German titles, and English subtitles) in which Chabrol chides Truffaut’s book on Hitchcock for “telling us nothing”—by which he means that Truffaut failed to get Hitchcock to spill his emotional secrets. This strikes me as both churlish and incorrect, because given how central class issues are to Under Capricorn’s themes and dramaturgy, the movie is already a highly personal and confessional expression on Hitchcock’s part about his working-class Cockney background, perhaps accounting for why he castigates himself so ruthlessly to Truffaut about the film’s making and its box-office failure. Chabrol doesn’t seem to realize that, according to the usual terms of English repression, Hitchcock is spilling his emotional secrets, onscreen and while speaking to Truffaut as well.

***

There aren’t any secrets spilled in Tony Zierra’s 2017 documentary Filmworker, which was reviewed by Robert Koehler in Cinema Scope 75 and is now available on a Region 2 DVD from Dogwoof. Its subject and focus is Leon Vitali, the English actor who played Ryan O’Neal’s rebellious adopted son in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) and then went on to pass up a promising acting career for the sake of becoming Kubrick’s all-purpose assistant cum slave, a function that he continues to embrace even long after the director’s death. So the main source of interest here isn’t so much Kubrick or his films as it is the kind of obsessive who would choose such an identity.

***

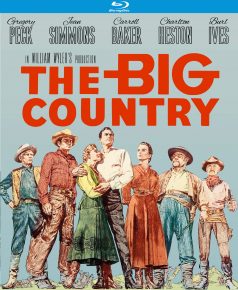

There are even more extras on Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray of William Wyler’s beautifully restored The Big Country (1958) than there are on Under Capricorn, and for me the best of these isn’t the hour-long documentary about Wyler, but one of its many outtakes: Charlton Heston explaining his initial bemusement about Wyler shooting portions of Heston’s climactic fist fight with Gregory Peck in extreme long shot, and his dawning discovery that this was done in order to show the futility of such violence—even though Wyler almost sabotages his point by also spelling it out in the dialogue, when Peck asks “What have we proven?” or words to that effect, in order to prevent us from concluding that Peck’s upper-class character is just as stupid as Heston’s working-class ranch hand for wanting to settle their rivalry with their fists. If we had previously concluded that Peck’s efforts to ride a wild, untamed horse in secret just to prove to himself that he can do it is somehow noble (a secret ironically betrayed later in the film by a stereotypically stupid Mexican ranch hand played by Alfonso Bedoya), Peck’s parallel desire to keep his slugfest with Heston a secret seems less noble because we know that such a fight is utterly pointless—so granting Peck the wisdom to see it as ridiculous and us the mixed pleasure of seeing it unfold in long shot lets both him and us off far too easily.

This points to my major qualm about The Big Country, a liberal parable that’s only four minutes shorter than Wyler’s equally class-conscious The Best Years of Our Lives (1946): that it simultaneously persuades us that violence is futile while milking our expectations of impending violence with a maximal amount of suspense and Pavlovian salivation. Nevertheless, the film remains gripping and fascinating to me for some of its performances (pace Michel Mourlet, for me Burl Ives and Jean Simmons are “axioms” far more than is Heston) and for carrying Wyler’s Bazinian passion for deep focus to cosmic proportions in those wide-open spaces. Indeed, there may be more cosmic long shots in this movie than in Kiarostami’s entire filmography, and even if the widescreen compositions aren’t quite as sexy as Anthony Mann’s, the landscapes are still pretty spectacular.

(Incidentally, although I’ve only sampled Christopher Frayling’s very informative audio commentary, which is also alert to the film’s anti-macho messages and resourceful in defending it against its many detractors, I have only one quarrel with it: namely, its claim that “character actor” Charles Bickford never played any lead parts. My counterevidence happens to be my all-time favourite Cecil B. De Mille feature, the talkie version of Dynamite [1929]. Even though Conrad Nagel gets billed ahead of Bickford, it’s clearly Bickford who deserves the star billing on this one.)

***

I’ve long considered Inherent Vice (2014) to be the worst Paul Thomas Anderson film (the most boring, and possibly the least persuasive in relation to period), just as its source is the worst Thomas Pynchon novel (the most sluggishly written, superficially felt, and glibly cynical in its multiple disenchantments, especially in contrast to the smarter and sharper observations of its more recent East Coast complement Bleeding Edge). But even so, there’s often more to both Anderson and Pynchon than first impressions suggest—or at least such has been the case for me regarding both Punch-Drunk Love (2002) and Vineland—so I decided to give the movie another try, without ever imagining I could ever want to go back to the novel.

Much of the movie is still pretty boring to me, maybe because I can’t believe in a millennial version of 1970 where everyone speaks in stoic, millennial Bogie imitations (whereas to the best of my recollection, people in the ’60s and early ’70s, stoners and straight types alike, tended to speak a lot more like Jonathan Winters in The Loved One [1965]), and as a mystery this is even more convoluted and less compelling than the Philip Marlowe capers that serve as its models. Pynchon’s obsessive preoccupation in all five or at least four of his last novels (I’m not sure about Mason & Dixon) with beloved radical heroines who fall sexually for fascists continues to sound like a stuck needle on an old 45, and the most Anderson can do with this plaintive theme is to soften the bleat a little by getting a secondary female character (played by Joanna Newsom) to take over Pynchon’s third-person narration. But at least Anderson has a pretty good cast to perform his mistaken version of 1970 (which probably functions as the “right” or at least most useful version for someone like himself, who was born that same year), including Joaquin Phoenix, Josh Brolin, Owen Wilson, Reese Witherspoon, and Benicio del Toro. Even aging hippies like myself who can’t really buy the underplayed hippies in this movie can still enjoy some of the thoughtful delusions of the millennials embodying them. There are no significant extras on the Warners Blu-ray—only four alternate trailers—but given the film’s disguised preachiness about tarnished innocence and bruised ideals, I suspect that an audio commentary or documentary might seem redundant.

***

I usually don’t get Cohen Film Collection titles sent to me unless I request particular items, but Masters of Cinema in the UK has been more generous in sending me their new releases, so it’s their version of the same 4K restoration of James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), in a dual-format release with a greater number of extras, that I have to recommend. Among the three separate audio commentaries—by critics/authors Kim Newman and Stephen Jones, Whale biographer James Curtis, and actress Gloria Stuart, respectively—it’s the latter that I cherish most, above all for Stuart’s intelligence and uncannily sharp memory.

***

Female Trouble (1974) has always been my favourite John Waters and Divine opus, not counting the slicker and more politically coherent Hairspray (1988), so I’m happy that Criterion has given it its full treatment, with such plentiful extras that you can even see extra footage of Divine in his male role (playing the character who allows Divine as a female to tell him to fuck himself) trying to get himself loaded with liquid so that he can barf all over Mink Stole (if that’s your idea of a welcome bonus feature). There’s also a video of the Waters entourage at the Warhol Factory that’s so poorly shot and/or preserved that it seems ready to evaporate the moment anyone sneezes, although I guess this is supposed to enhance its scuzzy authenticity.

For me, the passing of 44 years hasn’t improved any of the secondary cast’s atrocious acting, but once Divine’s gusto and Waters’ writing manage to persuade us to overlook such irritants it’s all clear sailing. The best appreciation of this movie that I know of is in a co-authored book of mine, Midnight Movies, but since J. Hoberman wrote nearly all of it I don’t think my endorsement qualifies exactly as vanity or as logrolling—or if it does, blame the chutzpah of Waters and Divine for empowering my own. I’ve long felt that North America would be a far better place if Waters, the closest thing my generation has produced to a countercultural Mark Twain, were hosting The Tonight Show, and even if his skills and art as a director have always taken a back seat to his writing, he’s always been an ace in terms of knowing whom he should hire.

***

I recently caught Jean Negulesco’s Phone Call from a Stranger (1952) for the first time on Turner Classic Movies, and found it intriguing and likeable enough to order the slim Fox DVD from Amazon, priced at $13.98. What most fascinates me about it—apart from its banking on its audience’s fears about fatal auto and plane crashes and swimming accidents, the comic stylization of two false and lying flashbacks related to Shelley Winters, the rare treatment of Michael Rennie as something more than an extraterrestial or an odd secondary character, the similarly uncommon employment of Bette Davis as an unbitchy character, and the ultimate redemption of the film’s most obnoxious character (played by Keenan Wynn)—is that it gives further evidence of Negulesco’s propensity for taking on three-couple plot structures in the ’50s: first in this black-and-white Academy ratio film, and then, in swift succession, in How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Three Coins in the Fountain (1954), and Woman’s World (1954), three assignments presumably designed to exploit the breadth and opulence of CinemaScope and colour.

Jonathan Rosenbaum