The Man Who Would Be Cinema: Muhammad Ali, 1942-2016

By Celluloid Liberation Front.

“Black is not a colour, it’s an attitude.” —James Baldwin

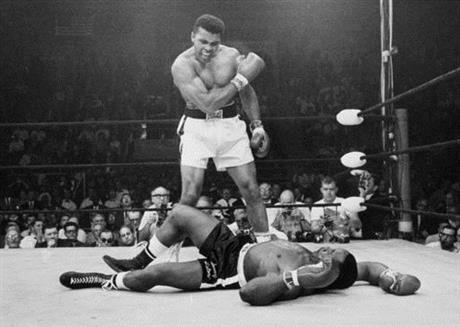

Heavyweight champion in the fight for racial equality and social justice, poet, rhapsodic loudmouth, adorable smart-ass, magician, wisecracker extraordinaire, Muhammad Ali, né Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., had survived his own death long before dying. No screen, big or small, will ever capture, let alone contain his boundless genius, for in Ali’s case the ring was but a launchpad to the world stage. Rather than simply a man history will remember as a demiurge of his own time, the creator and protagonist of outsized dreams of liberation. There is nothing to be written or said about Ali’s relationship with cinema, for the man himself was cinema. Very much like the seventh art at its uncompromising best, Ali transcended reality to project and inspire something nobler and more beautiful than the injustice of life on earth. A mythopoetic figure necessarily larger than life, Ali guided the steps of an exploited humanity at a time when it was still thinkable to demand the unthinkable. He conducted his life-long fight against the forces of oppression on multiple fronts, always on his own terms. As stylish and implacable in a television studio as he was in the boxing ring, his adversarial raps against the privileged white condescension of a William F. Buckley or a David Frost are as memorable as his jabs against Joe Frazier or George Foreman.

It took in fact another heavyweight of entertainment like Jerry Lewis to shut Ali up, or at least try to. On The Jerry Lewis Show in 1964, in the run-up to Ali’s fight against Sonny Liston, the king of comedy himself, aware of his sparring partner’s immense talent, taunted him with “You’re a big bag of wind” followed by “I think you’re the damnedest showman that ever lived and you ain’t kidding anybody.” He wasn’t indeed when in February 1964 at the Convention Hall of Miami Beach, Florida, he floored Liston in the seventh round and went on to became the heavyweight champion of the world. Yet that was but the prologue to the greatest fight of his life, that against imperialism and the United States government. At a time when the anti-Vietnam War movement was still in its infancy, Ali famously refused to be drafted. “I ain’t got no quarrel with no Vietcong,” he declared; and in fact, he had much in common with them. Like the Vietnamese resistance against the world’s most powerful army, Ali turned his physical inferiority before such towering opponents as Liston and Foreman into an asset. With the strategic ruses of a guerrilla, Ali finished his opponents only after having driven them to exhaustion through his legendary, dancing side-steps. When he was supposed to attack like an eagle, he flew like a butterfly. When everyone expected him to surrender, he stung like a bee, provoking his opponents by keeping his guard down, dancing around them, verbally taunting them and taking their blows only to stun them into oblivion with his lethal speed and surprise grapples.

For a man so consciously in charge of his own narrative, cinema would always struggle to live up to his intelligently scripted showmanship. Suffice it to say that the first time Ali appeared in front of a camera in a feature film, he literally knocked it out. A travelling shot takes us to a bar where punters lining the counter are staring in awe at a TV set broadcasting a boxing match. Cut. The audience is now facing the young Cassius Clay as he blasts away at the shaky camera until it falls. The two opening shots of Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962), written by none other than Rod Serling, perfectly exemplifies Ali’s relation with his audience: astonished ecstasy and admiration, and perhaps a touch of envy, met by a refusal to comply with the white gaze. Though his hypocritical embrace by pretty much anyone these days might suggest otherwise, Ali was anything but liked in his own time. As someone recently pointed put, the young Muhammad Ali would be considered a Muslim extremist by today’s (Western) standards. As The Nation‘s sportswriter Dave Zirin observed, “There has never been an athlete more reviled by the mainstream press, more persecuted by the US government, or more defiantly beloved throughout the world than Muhammad Ali.” Co-directed by Monte Hellman and Tom Gries, The Greatest (1977) is a re-enactment of Ali’s life interpreted by the man himself, along with Ernest Borgnine and Robert Duvall. For someone like Ali, a new cinematographic genre had to be invented: the auto-biopic.

It took the encounter between a radical white Jew and a black militant Muslim to give birth to the most explosive portrait Ali ever got on screen. Muhammad Ali: The Greatest by William Klein is by far the best documentary ever made on the “greatest fighter of all times,” more germane than Leon Gast’s When We Were Kings (1996) or Bill Siegel’s The Trials of Muhammed Ali (2013). First released in 1969, when Ali was nothing like the guy that even Fox News has now respectfully paid tribute to, Klein’s film still burns with the raw and seditious energy of Ali and his incendiary views. (A second version of the film was made in 1974, with material added from the “Rumble in the Jungle” match.) The director of the fashion-world satire Qui êtes–vous, Polly Maggoo? (1966) turned out to be the filmmaker best suited to capture Ali’s political significance. He had met and filmed Ali back in 1964 for a short called Cassius le grand, but most importantly he had followed and fraternized with representatives of Black internationalism from the streets of Watts to the liberation armies of Africa. Klein had also attended and filmed the first edition of the Pan-African Festival of Algiers for his eponymous documentary which celebrated anti-colonialism and its cultures, from the Black Panthers to Angolan freedom fighters. Hollywood had to wait for Ali to calm way down, and be sadly unable to speak as he used to, before granting him a biopic in 2001. Despite Will Smith’s inevitable yet respectful inadequacy, Michael Mann’s Ali is less of a disgrace than the spectacle of Bill Clinton delivering a eulogy at Ali’s funeral, for the crime bill he introduced filled the American private prison system with young black men to an extent beyond even Ronald Reagan’s wildest dreams.

The point though is that no director nor actor could ever compete with Ali’s natural talent for showrunning. Ali’s finest creation was probably his spectacular match with George Foreman in Zaire in 1974, where he managed to turn a publicity stunt organized by the unscrupulous Don King in a dictatorship propped up by the CIA into a play from the Theatre of the Oppressed. Surrounded by Secret Service lackeys, famous novelists, Uncle Toms, revolutionary leaders, ruthless businessmen and assorted extras, Ali talked directly to the tormented heart of the Black continent and listened to its jubilant children. When he landed in Kinshasa, a multitude of men and women, but most of all children, warmly received him with a chant that still resonates in the consciousness of history: ALI BOMAYE! ALI BOMAYE! ALI BOMAYE! ALI BOMAYE! ALI BOMAYE! ALI BOMAYE! “Ali, kill him”—kill the white man’s negro that George Foreman came to represent in the lead-up to the match, when he had turned up in Kinshasa with a German shepherd, immediately reminding the local population of the cruel and bloody colonial rule of Belgium. During that match, Ali carried his boxing strategy into dramaturgic perfection, and like a true performer took every single blow Foreman had to spare, incarnating the violated body of Africa beaten down by centuries of colonial theft. That night in Kinshasa, if only in the mythical space Ali had choreographed, centuries of slavery were vindicated by the People’s Champion. Boxing after all was for Ali what the revolution was for Lenin, a festival of the oppressed and the exploited, a muscular act of unbridled creativity able to overturn and transfigure the established order of things. To superimpose his emancipatory visions onto the reality around him was perhaps his greatest talent.

Even the sad end of his boxing career, which the Brothers Maysles immortalized in the 1980 documentary short Muhammad and Larry—where his former sparring partner Larry Holmes defeated Ali but cried instead of celebrating—speaks of his visionary refusal to take into consideration his human limits. Some say it was his entourage’s fault, some say it was for the money, but whatever the factual truth is, the symbolic significance of Ali’s return to the ring at 38 years old cannot be ignored. Like any mythical figure, age was a thing of no consequence for Ali, who decided to fight even that fight he couldn’t possibly win: the one against time. Though sad it is to watch a slowed-down Ali taking perhaps too many blows and knowing that this time there won’t be any upper-cutting retaliation, even his downfall looks grandiose. That is because until the very end, Ali refused to take reality and its limits for granted—he overcame them no matter what, even at the cost of his own health. The same verses he had penned when the Attica prisoners erupted in revolt are the best possible eulogy to his death but, most importantly, to his immortal life:

Better far from all I see

To die fighting to be free

What more fitting end could be?

Now while my blood boils with rage

Lest it cool with ancient age

Better vowing for us to die

Than to Uncle Tom and try

Making peace just to live a lie

Better now than later on

Now that fear of death is gone

Never mind another dawn.

Celluloid Liberation Front