Sandy Wexler (Steven Brill, US)

By Adam Nayman

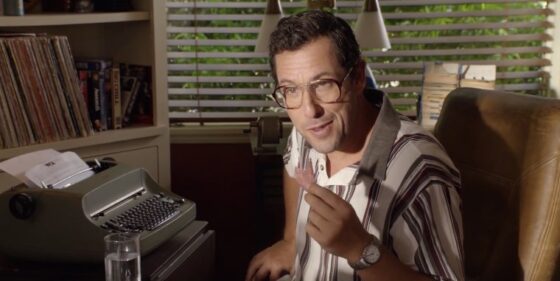

At the end of Sandy Wexler, the film’s eponymous Hollywood talent manager (Adam Sandler), who has come out the other end of a heart attack, grabs the microphone at a party filled with his showbiz family and belts out a nasal, atonal rendition of Irving Berlin’s “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Both the scene and the song evoke Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical phantasmagoria All That Jazz (1979), which deployed Berlin’s hooray-for-Hollywood standard in counterpoint to the caustic original songs by John Kander and Fred Ebb and similarly concluded on a note of ironic triumph, as stricken theatre director Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) lapses into a deathbed dream of a variety show featuring all his friends and collaborators, presided over by the Angel of Death.

If one allows that Sandler is the central creative force of his films, then it’s fair to state that Sandy Wexler—the third of eight features promised under the actor’s much-publicized content-creation deal with Netflix—is his own All That Jazz, albeit with the autobiographical element intriguingly displaced (and at a lugubrious 131 minutes, it’s a full eight minutes longer than Fosse’s own indulgent epic of the self). Sandler previously essayed a version of himself in Judd Apatow’s Funny People (2009), where he played a phenomenally successful but aloof and embittered mainstream comedy icon trying to live down all the crap on his resume with a last-ditch return to his scrappy stand-up roots. Sandy Wexler reverses the terms of the masquerade, with Sandler playing a fictional version of his former manager Sandy Wernick, casting his own wife Jackie as one of the hapless Hollywood lifer’s baffled clients, and, to complete the autobiographical inversion from Funny People (in which Sandler had awkwardly played house with director Apatow’s real-life wife and kids), having the two Sandler daughters appear alongside their parents. (Strangely, while Sandy’s roster includes performers of every stripe, the one thing missing is a hotshot young Jewish stand-up with his sights set on Saturday Night Live; it’s as if Sandler has cut himself out of his own creation myth.)

As all-in-the-family gambits go, the Sandler clan’s clowning is less affecting than the use of Paul W.S. Anderson and Milla Jovovich’s home movies in Resident Evil: The Final Chapter, but it does signal that Sandy Wexler is a project that is far more personal for Sandler than, say, The Ridiculous 6 (2015). Shot in flat, depthless digital video by Dean Semler (his sixth outing as DOP under the Happy Madison banner) and lazily directed by Steven Brill (who’s probably third on the depth chart of Sandler’s pet directors, after Frank Coraci and Dennis Dugan), Wexler isn’t a particularly good movie, but it’s mesmerizing all the same, projecting a strange mixture of heartfelt homage, reactionary nostalgia, lowbrow integrity, and contractually obligated indifference that turns nearly every scene into a tonal rollercoaster.

Sandler has stated that the film was intended as a gesture of thanks to the first person in the industry who believed in him, but the fondness he thinks he’s displaying for Wernick—who he reimagines as an awkward, leisure-suited hustler who consistently makes bad calls and is congenitally incapable of telling the truth or closing a deal—continually jostles against the condescension of his portrayal. The conceit is that underneath his thin layer of flop sweat, Sandy is a big-hearted naïf, which elevates him above all the mercenary careerists in his midst and makes him a hero. Sentimentality is the bank holiday of cynicism, as a pre-Sandlerian wit once put it, and it’s harder to take Sandler as an unsocialized underdog now than it was 20 years ago in Billy Madison (1995) and Happy Gilmore (1996), when this shtick was all a bit more spontaneous.

What may make Sandy Wexler affecting for viewers of a certain age—i.e., second-wave Gen-Xers for whom Sandler’s goony prince-of-all-media act was a gateway to all kinds of slightly outré amusement—is its vividness as an early-’90s period piece. Shuffling through the streets of Los Angeles, Sandy passes billboards advertising R.E.M.’s Monster and Hole’s Live Through This; he thumbs through glossy, immaculate copies of Variety and Cosmopolitan, guzzles Fruitopia, and pledges his allegiance to the local Blockbuster Video. The comedic nutritional value of these references is nearly zero, and yet in their way they’re as telling as the names dropped in any Woody Allen movie of your choosing—let’s say Broadway Danny Rose (1984). (There’s also an echo of Zelig [1983] in the obviously improvised and generally endearing testimonials to Sandy’s greatness—or lack thereof—from authentic, ’90s-era C-list celebrities.) Like Allen, whose aversion to the present tense is a pathological running joke now in its sixth-running decade, Sandler seems intent on retreating into his own pop-culture comfort zone, which not coincidentally coincides with the era of his greatest success: a time when people went in droves to see Adam Sandler movies on opening weekend, instead of streaming them distractedly in the comfort of their own homes.

Sandler’s fanatical insistence on the archaic even extends beyond the millennial timeframe. Note, in another evocation of Allen’s Danny Rose, the weirdly old-school specialties of Sandy’s clients—a daredevil (Nick Swardson), a wrestler (Terry Crews), a ventriloquist (Kevin James)—and the way the plot, which involves the making of an ascendant, Mariah Carey-esque pop star (Jennifer Hudson), luxuriates in the now-outmoded details of A & R tactics, radio play, and reel-to-reel studio recordings. On a more contemporary note, a determined and sympathetic viewer could perhaps make a case that white knight Sandy’s discovery, support, and accidental seduction of Hudson’s Dreamgirl reveals a rarely seen progressivism in the Happy Madison universe in the casualness of the couple’s interracial partnership (which is even blessed by Hudson’s dad, played—because why not—by R&B legend Aaron Neville). But these sops to our supposedly more enlightened sensibilities must be weighed against the Sandler crew’s usual smug, post-PC posturing (e.g., Rob Schneider in Middle Eastern drag); thankfully, there’s considerably less aggressive and gratuitous gross-outs here than there were in That’s My Boy (2012), which paired Sandler with his spiritual heir Andy Samberg and, for whatever reason, ranks highly with the Sandlerphiles in my critical circle. (My own vote for faintly glimmering highlight in the wasteland of Late Sandler goes to Al Pacino’s jaw-dropping “Dunkacino” rap in the abysmal Jack and Jill [2011].)

One could speculate that the box-office failure of this strained attempt at generational torch-passing not only helped drive Sandler to the world of straight-to-streaming distribution, but reaffirmed him in his backwards-looking convictions. It’s been noted often in recent years that Sandler now looks to be making movies as much to score paid, quasi-working vacations for himself and his friends (see the Grown-Ups series, as well as the African excursion of Blended [2014]) as to entertain his fanbase. There is safety in numbers, and Sandler’s omnipresent onscreen entourage—which in Sandy Wexler includes not only the usual batch of third-and-fourth-tier ex-officio SNLers (Schneider, Jon Lovitz, Kevin Nealon, Colin Quinn), but such past-their-expiry-date icons as Vanilla Ice, Penn Jilette, and “Downtown” Julie Brown—surely speaks not only of genuine friendship and loyalty (if we may say such things truly exist in La La Land), but of a fading icon surrounding himself with physical reminders of his past glory.

And so we return to Wexler and its climatic Sandy-Sandler sing-along, which even continues over the end credits with off-the-cuff footage of the cast clowning their way through their pal/patron’s lusty serenade. Where song-and-dance man Fosse envisioned his own end as a production number in the Great Beyond, Sandler and company here offer us a world where the ’90s never ended, the bar is always open, and the party goes on forever. And if one finds the circle-the-wagons insularity of these credit-rolling shots of C-listers hitting the bar to be more authentic and persuasive than Sandler’s pantomime of selfless humility, well, that’s showbiz for you.

Adam Nayman