Festivals | RIDM 2019: Adapt or Die

By Justine Smith

The world is in turmoil, and at this year’s Recontres Internationales du Documentaire de Montréal, documentaries from around the world grappled with our new reality. Drawing from a wide range of experiences and approaching the idea of non-fiction from an array of perspectives, the films showed a diverse programming mandate; meanwhile the uncertainty, unrest and paranoia shared by the titles on offer casted a veil over even the most lighthearted of subjects. A dark future casts a shadow over the present. Hope is not entirely lost, however, and our parasitically adaptable species can find glimpses of hope in community, art, and even football.

Recouping a nation is at the heart of Dieudo Hamadi’s Kinshasa Makambo, which chronicles the organization of a youth uprising against the Democratic Republic of Congo’s current leader, President Joseph Kabila, who has refused to step down since 2016. Elections have already been postponed twice, and Kabila is now scheduled to resign in December 2018, but his opponents are uncertain he will keep his promise.

Hamadi made one of 2017’s most striking films, Maman Colonelle, which portrayed Honorine, a woman who works in various neighbourhoods in the DRC, protecting children and combating sexual violence. Kinshasa Makambo expands that vision, as the collective political organizers serve as the principal characters and the point of entry. The film takes us to the streets and into backrooms of Kinshasa, where young men and women debate the best strategies against an increasingly militarized police force. Maman Colonelle and Kinshasa Makambo are sharp and vital films that explore the small but meaningful efforts of a citizenry to improve the conditions of their nation; they have the same modest but focused effect as their subjects.

The images are familiar but specific; young men in the streets screaming for voting rights, raising their unarmed hands to the sky as they push forward. One of them, looking not quite at the camera but in its direction, screams that cops cannot do anything as long as the white journalists are watching. Does our gaze offer him protection? This first protest seems relatively peaceful, in spite of police pushback, but aggression mounts towards a deadly interaction that Hamadi strategically and humanely articulates not in video but with a photo slideshow of dead protesters.

It is the backrooms of power where the gravity of the situation can be glimpsed. One protestor explains his attempt to immigrate to America, where he felt, “so alone”; even under the threat of violence, he prefers to return to his homeland to help rebuild it. Another discussion involves a potential action for change, as a man suggests the importance of dialogue with the regime, which is shot down: “You think writing ‘Kabila step down’ on Facebook is enough?” The protestors agree a dialogue is impossible with a government that has already ignored the constitution, but will non-violent action be any more effective?

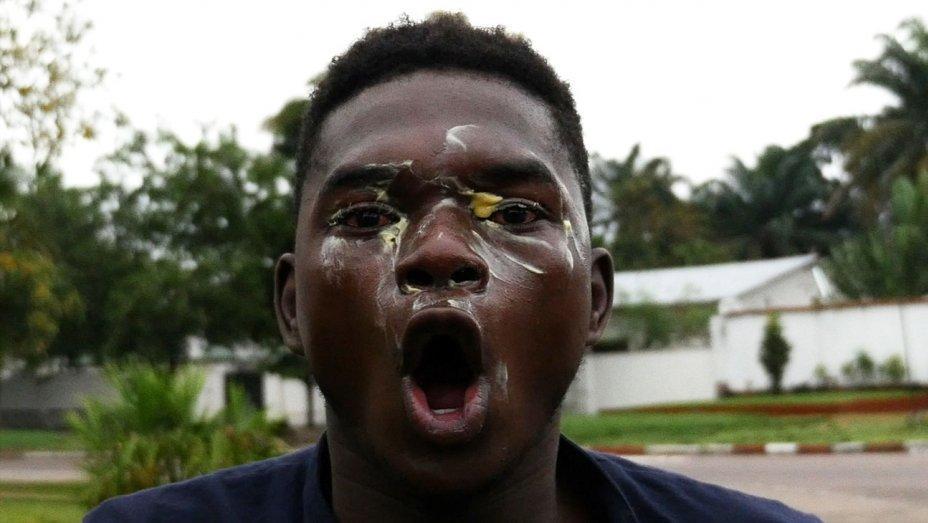

The open-endedness of this question probes the ongoing sense of compromise and resistance at the heart of this collective. They not only discuss how to trigger an election but offer practical solutions to unequal protests where the police will use disproportionate force. In a striking sequence, a group of young men don gas masks made from plastic bottles, their faces smeared with butter, which is meant to lessen the effects of certain chemical gases. In silence, they sit in wait with flies buzzing around them, attracted to the lard that starts to drip off their faces. The resilient patience of their years-long resistance against an undemocratic regime weighs heavily in this almost fantastical vision of garbage-made armour.

Hamadi’s cinema is admirable for its patience in constructing the complicated and often competing narratives of effecting change. He often finds optimism in collective organization, as different people assemble to find practical solutions to problems in their communities. With an observational style, he strongly suggests the often unfair or weighted circumstances that his subjects face, while also highlighting the physical labour of their endeavours, humanizing their efforts as practical resistance within reach.

With the growing influence of social media, it’s unsurprising that many politically minded films transpire with Facebook, blogs, and the internet in the background. One such film, Nebojsa Slijepcevic’s Srbenka, is about the production of a play about the murder of a young Serbian girl during the early ’90s, and is made against the backdrop of right-wing public pressure. Blurring the line between artifice and reality, Srbenka portrays a series of improvisational rehearsals during which the ambitious director, Oliver Frljic, encourages actors to integrate their own life experience onto the stage. As Frljic becomes increasingly obsessed with the right-wing condemnations of his production, which play on all-too-familiar xenophobic and nationalist ideals, he integrates into the play fourth-wall-breaking interludes that confront its critics directly.

While Oliver’s obsession with his right-wing opponents certainly infects the production, the stage remains a democratic place of debate and workshopping. People butt heads but are able to find common ground and compromise. Hurt but energized by the calls to censor his work, Oliver obsessively seeks to use his art as an answer to rising fascist sentiments in his milieu. Can art make a difference to effect social change? It seems unclear, but the film does point to an immediate effect, in particular, a young actress who is moved to no longer hide her ethnic identity.

Mostly told through conversations between the filmmaker, Corneliu Porumboiu, and his subject, Laurentiu Ginghina, Infinite Football portrays the small efforts of a man’s desire to “fix” his favourite sport. After a traumatic childhood injury, Ginghina decided that his injuries could have been avoided if football had better rules. Through a variety of conversations taking place in Romanian gyms, his workplace, and outdoors, Ginghina discusses his various proposals. What begin as rather simple changes, however, become increasingly more complex, trading the simple purity of the sport for a needlessly complex set of regulations that hamper movement. Football becomes an apt metaphor for life as this man tries to use his desire to reinvent the game as a way of fixing the bonds of his society. The shift in the film from Ginghina’s insistence that “the ball must be free,” to have it be so constrained by rules that players can only make back passes, is a compelling parable on the challenges of self and social improvement.

In Claire Simon’s Young Solitude, the camera is a fly on the wall as teenagers in a French high school discuss loneliness. The closeness of teenagers, who are going through the hormonally volatile years of not being able to contain one’s emotions, allows these conversations to flow naturally—even if they are unnatural confessions, likely prompted or guided by a filmmaker. Touch plays a big role, as one young man begins to cry because of his father prefers eating dinner at his desk rather than interacting with the family—wordlessly, his friend reaches out and puts his arms around him. He is disarmed and relaxed by the simple gesture of physical intimacy.

Another girl, when asked what she wants from her life answers mournfully, “I know who I want to be, but I don’t know who I’ll be.” Even if we can imagine where we want to find ourselves down the road, there is no certainty we will make it there. As these films face down uncomfortable futures, they confront impossible questions and compromises needed to effect meaningful change, from fighting against the odds for a better world to rewriting the rules of the game.

Justine Smith