You Can’t Own an Idea: The Films of James N. Kienitz Wilkins

By Dan Sullivan

Rare these days is the filmmaker who proclaims that cinema is firstly a medium of ideas rather than of images and sounds, and few have made the case as strongly as James N. Kienitz Wilkins. For the better part of the past decade, the 35-year-old New York-based artist has occupied a singular position on the periphery of American independent filmmaking. His films—four features and seven short works for cinema, installation, and even planetarium (The Dynamic Range, 2018)—fail to easily place him within any particular scene or tradition. A classmate of Gabriel Abrantes and Alexander Carver’s at Cooper Union, he has, like them, straddled the film and art worlds; within the film festival context, he has moved freely between narrative and strictly experimental sections, not quite a new member of the avant-garde establishment nor an up-and-coming fashioner of droll microbudget films. Seemingly resistant to the idea of carving out a single position for himself and maintaining it for very long, the prolific Wilkins has launched one of the more strikingly frenetic investigations into the life of the mind and the lives of artists, race, money, and technology in recent cinema, playfully and thoughtfully posing tough questions about the features of the contemporary world we tend to take for granted.

The status of language and writing within cinema and culture more broadly is a major concern throughout Wilkins’ work. His first feature, Public Hearing (2012), openly challenged the conventional understanding of what a screenplay can be. Starkly lit and shot on familiarly grainy black-and-white 16mm, Public Hearing is a filmed re-enactment of a 2006 town-hall debate in Allegany, New York, concerning whether a local Walmart should be allowed to be replaced by a Super Walmart, the cases for and against presented by a panel of speakers who are framed by Wilkins with the sort of effortless artfulness of prime Frederick Wiseman. Public Hearing is something of an extravagant gag: a film which superficially resembles canonical works of cinéma vérité, but unlike them, it has in fact been scripted, sourced from a publicly accessible PDF transcript for the sort of event, barely recognizable as such, that would never otherwise be represented in cinema on account of its extreme banality. If not for the skillful, visually satisfying way in which Wilkins renders the proceedings, we might almost say that Public Hearing, like certain films of Andy Warhol, is a film one doesn’t need to watch in order to “get the joke.” The narrative information that the film conveys is readily available to anyone with internet access; anyone with the inclination and the resources could conceivably have made it, perhaps complicating our perception of Wilkins as the film’s author in the classical sense. The text of Public Hearing stands apart from its staging, capable of being wrested from this aesthetic context—a tasteful, faithfully reproduced cinematic treatment—and placed in another. (Although, in later films, Wilkins will make the case for why cinema is the ideal medium for capturing our historical present in all its majesty and inanity.) The written word, readymade or not, refuses to be exhausted by the conventionally pleasing images Wilkins composes to represent it. The gesture is positively Duchampian, the porcelain urinal replaced by a PDF.

In Wilkins’ films, considerations of language are never far from the question of technology, specifically the relationship between the internet and the imaginary. After all, how would we access a PDF transcript of a 2006 town hall meeting in Allegany, New York if not online? Technology mediates our perception of the world around us and of our own interiority, and by forwarding us a steady stream of New York Times articles, prestige television shows, NPR interviews, and so on, it likewise populates our imagination with characters, scenarios, and settings, effectively providing the material for the fantasies staged within the subconscious. The short films that comprise Wilkins’ “Andre” Trilogy—Special Features (2014), Tester (2015), and B-ROLL with Andre (2015)—explore the fault line between the technological and cultural realms, each of them using found (or pseudo-found) elements to consider the extent to which popular culture has essentially authored our dreams.

Special Features assumes the form of an interview, filmed with an old video camera, conducted by Wilkins with an African American man (played by three different actors at various points of the film) who recounts a dream (or was it?) involving another man—the trilogy’s titular Andre—working security at a party at Shaquille O’Neal’s house. (“It was plotted like a movie, so vivid,” he says.) But his dream’s significance seems to reside not in its psychoanalytic implications, nor in the metaphysical contradiction its subject embodies (the living dead), but in technology and the internet’s role in determining the contents of his story. The man’s account most closely resembles a hazy recollection of a YouTube video viewed at some uncertain point in the past, and Wilkins seizes upon this narrative fuzziness to blur the lines between both plain old lived experience and technologically mediated experience (is there any difference?), fiction and truth, and the virtual and the actual. The film plays with the instability of the interviewee’s identity, being incarnated by three different actors, but also with the question of how a man who claims to have died could be sitting before us making jokes about Shaq’s lone career three-pointer—after Wilkins explains to him that the interview is being shot with three-point lighting. If not for Wilkins’ deployment of the artifice of cinema, this character could not exist, yet the contents of his story—fragments of movie plots, sports trivia, news articles—would. Contemporary identity is forged in the crucible of technology as much as that of culture, for better or worse.

Tester and B-ROLL with Andre also meditate on the unconscious and metaphysical effects of technological development, and they bring language back into the thematic fold in a more concerted way by introducing Wilkins’ penchant for monologue. Tester combines an old found Beta SP tape shot within a nondescript office park-like setting with a soundtrack that begins with an ironic blaring guitar solo before giving way to a mile-a-minute comic gumshoe voiceover. The text delivered, written by Wilkins, is dense with alliteration and wordplay, and it returns to the dream thematic established in Special Features as well as technology’s uncanny transformation of the physical and mental realms. In B-ROLL with Andre, the interview and monologue forms are folded together to address the economic dimension of cinema. The film is a stylized, staged interview of a man whose face has been obscured, and Wilkins has him muse on the shifting meaning of everydayness in an increasingly virtual world (“Just drinking a cup of coffee—that’s the kind of thing that appealed to me”) and pitch a movie about digitally savvy art thieves entitled eBoyz. The prospect of earning money for one’s ideas connects Wilkins’ preoccupation with language to his nascent interest in the artist as an economic subject who attempts to make a living within an industrial context. But it also finds him beginning to situate his own work within the world of cinema at large: he uses an excerpt of Trent Reznor and Atticus Finch’s score for David Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014) to (however ironically) inject canned atmosphere to the proceedings, though the interviewee refers to it as “the whitest film noir”; the question of how to make money without compromising one’s artistic and intellectual integrity while working in a capitalistic and frequently corny mass medium like cinema will recur time and again in Wilkins’ subsequent films.

Occupations (2015) finds Wilkins more or less abandoning the irony of Public Hearing and the Andre Trilogy in its portrait of an occupational therapist, Brandon D’Augustine, whom we see driving at night and wandering in snowy woods, unpacking the concept of “occupation” (understood as how one spends one’s time, rather than how one earns one’s rent) as images of golden bodies posed against a black background are intercut and matched with a faint church organ played by Wilkins’ mother. Wilkins highlights the relevance of D’Augustine’s therapeutic practice to filmmaking—after all, film production is hardly a purely mental activity, and an artist must create by relying upon a physical body that can break down and fall into disrepair. This materialist turn, introducing bodies to an artistic investigation that had previously been more concerned with abstract phenomena like ideas, cultural signifiers, economic practices, and the like, sets the table for Wilkins’ later, theatre-minded works Mediums (2017) and The Republic (2017), but the film also lays bare the personal dimension of his work through the inclusion of his mother’s organ-playing, and its images of D’Augustine walking in the woods that evoke Wilkins’ native Maine.

Few of Wilkins’ films resemble one another stylistically; his is a particularly restless formalism, and each film seems to find a new mould into which he pours his pet obsessions. Common Carrier (2017) is among the most visually adventurous of his long-form experiments, a feature-length quasi-narrative film that consists almost entirely of superimposed images of a disparate network of artists grappling with financial anxiety both in life and in art. The film’s action wittily goofs on the festival circuit (including an entire subplot about a DCP drive lost by FedEx) and the film industry, bad-faith liberal failures at achieving real solidarity with the American working class, and the ubiquity of hip-hop music counterposed to the US’ history of racism and the ongoing economic oppression of its black population. His use of pop music recorded off the radio, most notably several tracks from Rihanna’s 2016 album ANTI, is particularly instrumental on this last count, with the juxtaposition of “Work” and an image of a hammer striking an awl suggesting capitalism’s simultaneous profiting off black music and systematic mistreatment of black labour.

But as dense as the narrative of Common Carrier is with ideas about race, cinema, and labour, it is just as rich pictorially. The film’s visual conceit—near-constant, start-to-finish superimposition—isn’t necessarily wholly successful, but at several points it obtains a radical flourish unlike anything else in Wilkins’ oeuvre. Actions are viewed from multiple perspectives at the same time that image and sound weave in and out of synchronization, our view of the proceedings charged with the same sort of schizoid anxiety that marks the capitalist processes underlying the events of the film’s plot. Space and time are collapsed into one another just as capital perpetually collapses art and commerce, labour and exploitation, violence and spectacle to create an unstable, anxious economy defined by mass consumption, financial precarity, and social control through debt. At one point, Wilkins’ character describes a figure from a dream, “a blur of a million people I’ve seen before,” and later talks about meeting someone who was, somehow, a perfect synthesis of two other people he’d met before—the delirium conjured by the film’s visual conceit mirrors the indeterminacy of social reality under today’s capitalist regime, a frenzy of branding and scamming without end.

In 2017, Wilkins unveiled two rather idiosyncratic works focusing on his relationship to theatre: Mediums and The Republic (the latter in collaboration with Robin Schavoir). Mediums, which premiered in that year’s Whitney Biennial, marks the apex of Wilkins’ tendency to predicate a film’s form upon a kind of joke. A medium-length film (nearly 40 minutes) comprised entirely of medium shots (static tableaux, two- and three-shots mostly, of actors posed against an uncannily artificial set comprised of massively blown-up images), it tracks a series of conversations between a group of prospective jurors passing time outside a courthouse on the first day of jury duty. The dialogue is culled almost entirely from found sources, as listed in the film’s credits: the New York State Unified Court System’s Trial Jurors Handbook; a Volkswagen manual; the SAG-AFTRA constitution; Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire (1996); a franchise disclosure document from Dunkin’ Donuts; copy from the New York State health plan marketplace; text from the US Copyright Office’s website; and a few blog posts. The earnest tone of the dialogue strikes a fascinating counterpoint to Wilkins’ laissez-faire borrowing of text, and its self-conscious mise en scène—the bodies of everyday people posed against a backdrop of a simulated courthouse, sometimes with a view of the Dunkin’ Donuts across the street—embodies Wilkins’ interest in the relationship between cinema and theatre. There’s little that’s quintessentially cinematic about Mediums, but Wilkins is aware of this: the film represents dramatic art degree zero, in a sense the bare minimum required for something to even count as a film, but it nevertheless surpasses the earlier Public Hearing as an uncommonly funny work addressing the ontological question, “What is a film?”

An even more radical work on cinema’s relation to theatre is The Republic. Three-and-a-half hours long and devoid of images, The Republic “stages” an entire play—old libertarians pursuing their own version of utopia by any means necessary (don’t tread on them). The film has an accompanying illustrated screenplay (accessible on Wilkins’ website, automaticmoving.com) that hints at the circumstances that catalyzed the completion of this singular work. Without the money necessary to film a script as ambitious as The Republic, Schavoir and Wilkins instead produced it as a film without a visual dimension. The action of The Republic, whose title self-consciously evokes Plato, unfurls entirely within an epic cascade of actorly voices, suggesting a radio play for the internet age: the absence of images encountered in watching the film conjure both virtuality (the film that could have been, the film that might someday be) and self-reflexivity (by design, the experience of viewing The Republic is about the question, “Is this a film at all?”). Theatre without presence, cinema without images—that The Republic nevertheless feels like a formidable work of both mediums attests to the sheer substantiality of Wilkins and Schavoir’s experiment.

Wilkins’ next short, Indefinite Pitch (2017), consists of a succession of black-and-white photographs of neutral nature scenes—shimmering water, twigs on the perimeter of a pond, etc.—while most of his central themes are encapsulated by a single breathless monologue that accompanies these images. Indefinite Pitch fixates on Berlin, New Hampshire, notable for, among other things, the fact that it is named for the German capital, and for its proximity to Maine. (Though Wilkins is careful to note that, at the time of the film’s completion, he had never been to Berlin in New Hampshire nor in Germany.) More pertinently, Berlin, NH is the setting for a 1927 pulp film serial, The Masked Menace, which, by some associative alchemy, prompts Wilkins’ monologist to pursue a line of thinking that connects economic discomfort (“I need money,” he states plain and clear), to the psychic burden of racial circumstance (“We’re born with our masks”), to some aspirationally even-keeled resignation to the quotidian present (“I confess I’m going with the flow”), to the folly of the film-industrial rat race (he concludes on the desire to submit the film to the “Berlin Film Festival”—which, ultimately, he didn’t, instead premiering at Locarno). But curiously, Wilkins sees something upright in the cinema versus its more humourless counterpart, the art world: he cites cinema’s status as a mass medium, an art accessible to rich and poor alike, as its redeeming quality, the inverse of the stratified, access-impoverished and status-hungry world of fine arts. The monologue’s pitch shifts considerably across the film, forcing Wilkins’ voice in aurally cartoonish directions, but this too turns out to be grounded in an impeccable turn of thought. He evokes the early years of sound cinema and the pitch-shifting exercised by sound editors to ensure that a film’s soundtrack would retain synchronization with the image, and at the very same time, Indefinite Pitch itself—a digitally produced film projected within a cinema on DCP or streamed via Vimeo, MUBI, etc., on a computer—visually meditates on the ramifications of a film that generates a frame rate in the absence of perceptible motion.

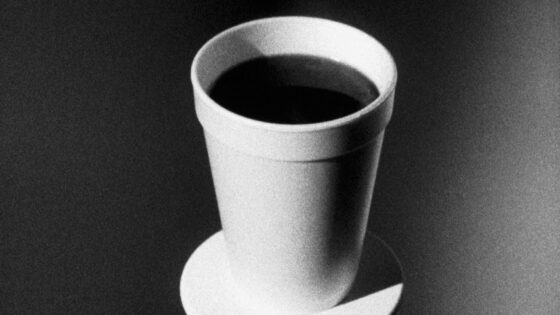

“The way I see it, movies move,” Wilkins declares in his subsequent monologue film, This Action Lies (2018), made for Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève’s Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement. A styrofoam cup of coffee is viewed several times, with fluctuations in gradient distinguishing one Warholian long take from the next. The voiceover claims to be delivering an apology, but instead uses the concept of the apology as a point of departure for a rambling investigation that again revisits the question of the medium’s ontology, though now with a mind to material considerations: Wilkins equates life with movement and proclaims cinema the art of movement, but he also, after wringing his hands over the fate of a DCP-containing thumb drive in Common Carrier, now worries about the physical manifestation of his own work. What does it mean for a film to exist and yet never assume the form of a celluloid strip? Not eager to find out, Wilkins speculates as to how to get a hold of a curator in the film department at the Museum of Modern Art, step-by-step tracing the route by which one might figure out how to get a hold of an employee of a prominent cultural institution, hoping that they’ll elect to strike a print of one of his films.

But just as salient as his anxiety about his own career is his anxiety about having newly become a father: suddenly, all of his frustrations about being an artist are refracted through the prism of familial obligation, now having to make a living for himself and for others. It helps to retain his ties to the everyday, though—Dunkin’ Donuts is again dissected at length, linked to the charmingly proletarian incompleteness of construction sites, regionalism (through its cultish popularity in its founding New England), and the physical movement of dunking one object into another. At this relatively late stage of the game—nearly seven years after the completion and premiere of Public Hearing—Wilkins characterizes his own approach in This Action Lies as “searching for a method,” echoing the title of an essay by Jean-Paul Sartre that served as the introduction of his second systematic masterwork, the Critique of Dialectical Reason. But more primarily, This Action Lies evokes Sartre’s fellow countryman, Marcel Duchamp. The urinal is again replaced, this time by a styrofoam cup; the “R. Mutt” signature replaced by a voiceover narration that digs into the perils and anxieties of a working filmmaker living in a capitalist society who has just had a kid. The documentary quality of Wilkins’ work is one of its subtlest and most crucial, and the affecting fullness with which he captures the quotidian psychology of our age in his monologue seems to substantiate his belief in cinema’s capacity to document one’s historical circumstances, despite its easily misguided, capitalist nature.

Wilkins’ signature is everywhere evident in Peter Parlow’s feature-length The Plagiarists (2019), which he co-wrote with Schavoir and shot/edited himself with a vintage Betamax camera. (Wilkins produced Parlow’s debut feature, The Jag [2015], a chamber play about escalating tensions between a hipster carpenter/aspiring screenwriter and a troublingly uptight venture capitalist in an upstate country home.) More classically narrative than Wilkins’ own features, the first half of The Plagiarists chronicles the experience of a bobo couple, a novelist named Anna (Lucy Kaminsky) and a frustrated would-be filmmaker named Tyler (Eamon Monaghan), who are waylaid by snow and car troubles en route to their friend Alison’s (Emily Davis) house upstate. They’re bailed out by a chance encounter with Clip (Michael “Clip” Payne of Parliament Funkadelic), who offers to give them shelter for the night and to hook them up with a mechanic friend in the morning. Hesitantly, they take him up on this, and the trio proceeds to spend a mostly affable evening cooking, drinking, shooting the shit, and chopping it up about Dogme 95 and what a bummer it is shooting commercials with soulless contemporary digital cameras at some impossibly high resolution. Anna and Tyler are confused by some details about Clip—for instance, who is the inexplicable little blond white boy playing video games upstairs in his house? And how does he know Alison?—but two of his gestures prompt them to overlook the ambiguity, at least for the night. First, he gifts tech-geek Tyler an old industrial-grade video camera (not unlike the one on which the film is shot) for use in his artistic and commercial filmmaking practices, and he delivers an intensely lyrical reminiscence of his youth to Anna that, though seemingly out of character, moves her profoundly. Flash forward some months later, and the couple is again on their way to stay with Alison, bickering in the car while Anna thumbs through a copy of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, Book 3. She is alarmed to stumble upon a passage in the novel that feels oddly familiar: lo and behold, Clip’s earlier soliloquy was plagiarized wholesale from Knausgaard. The discovery rattles her, and the remainder of the film finds her discussing the matter with Tyler and Alison. What’s the big deal exactly? On what grounds does this constitute a betrayal of Anna’s trust, and why can’t she help but feel violated?

Wilkins and Schavoir’s script attributes the couple’s unsettled feeling to a quintessentially modern form of race panic, whereby the nominally liberal white couple are fully aware of the racial dynamics at work in their relationship with this black stranger whom they’ve only briefly met but are nevertheless beset by a cloying sense that something is off, something is worth being afraid of. Parlow, Wilkins, and Schavoir again wield cinematic artifice to concretize this feeling through the film’s form: Clip never occupies the same handheld frame as Tyler and Anna, and indeed, Michael Payne was never physically present on set at the same time that Monaghan and Kaminsky were. (The three actors, at the time of this article’s writing, have never all met.) This sly gesture is referenced within the film itself: when Tyler and Anna are driving in its second half, a review of Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here (2017) plays in the background on NPR.

The film riffs on the plagiarism theme manifest in its title not only through Clip’s apparent act of uncredited quotation but through its own poster, which is quite close to being a carbon copy of the poster for Ricky D’Ambrose’s Notes on an Appearance (2018), a film in which Wilkins appeared in a small role. The theme of intellectual property that has recurred sporadically throughout all Wilkins’ work thus returns, front and centre: downplaying his own artistic aspirations and achievements, Tyler tells Anna “a screenplay is just an idea, it’s not a film…you can’t own an idea.” Of course, the gag here is that, in a sense, Wilkins and Schavoir had previously made a film, The Republic, which assumed the form of a screenplay read aloud, but buried beneath the joke is a barbed observation about the now-tenuous relation between the act of writing and the recognition of ideas as property that can gain and lose value and can function in the broader marketplace, just like the aspirational stake in a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise mentioned in Mediums.

As in Common Carrier, The Plagiarists links the myriad frustrations of the life of an artist to technology. Tyler hates the work he has to do to make a living, in part because it forces him to work with cameras that produce images which are too clean and insufficiently stylish, that don’t seem to issue from the past. Tyler neglects to explain why an image must look old in order to be art, but this is precisely the sort of unexamined attitude that would be at home within the artistic milieu that The Plagiarists skewers. The film’s dialogue ironically evokes Dogme 95, mumblecore, and the like, though the film itself bears a strong superficial resemblance to them. For all its jokes at the expense of Parlow’s lo-fi forebears, The Plagiarists is something like a conceptually baroque homage to the very films and filmmakers it is taking the piss out of, with a wealth of silly, jazzy stock music (given full attribution in the end credits) on the film’s soundtrack further emphasizing its own irony. Schavoir and Wilkins manage to have their cake and eat it, too: the provocations of their script and Wilkins’ uncanny editing structure—stitching together images of actors who never physically shared the same space—are inextricably bound up in its pleasures. “The feeling of being talked to by a real human voice is needed now,” Alison says in a letter read in voiceover during the film’s final sequence. I would only add that there is one voice in particular, Wilkins’, which ranks among the most necessary in cinema today.

Dan Sullivan- « Previous

- 1

- 2