Star Wars: Laura Poitras’ Astro Noise

By Jerry White

“I should rewatch The Man Who Fell to Earth, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and All the President’s Men.”—Laura Poitras, “Berlin Journal,” February 7, 2013

“For those who listen, the stars are singing.”—Edward Snowden

Just after making it though Astro Noise, Laura Poitras’ new exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art (whose catalogue is the source for both quotes above), the friend I was with told me I should really check out the floor below us, which housed some of the permanent collection. He’s a long-time New Yorker, a film editor whose fine sense of his craft is informed by decades of taking in all the city has to offer in terms of visual art and cinema. So naturally, I obeyed, and after rounding just one corner, Joseph Cornell’s 1958 box Celestial Navigation jumped off the wall at me. I had seen it years ago, when the Whitney was still way uptown and not in its sleek new digs in the Meatpacking District. It was as delightfully weird and goofily Cornellian as I remembered, but in light of the Poitras exhibition it suddenly took on a much more brooding aura. The little plastic head attached to the side by nails, its face partially broken off, felt truly shattered; the little slab of wood attached below it, barely painted and also sloppily broken off on both sides, gave the thing a sense of ruin. Cornell was still trying to evoke the pure and heavenly music of the earth moving on small metal rods, but his was a vision from the perspective of the fallen world.

What it made me think of immediately was the moment in Citizenfour (2014)—the Oscar-winning film that documented Poitras and Glenn Greenwald’s hotel-room rendezvous with Edward Snowden as he prepared to air the NSA’s dirty laundry to the world—where Poitras’ taxicab emerges from a tunnel in the heart of Hong Kong: the sense of forward motion into a new world, a new consciousness, was visceral and overwhelming at the same time as it was quotidian. That this sequence was an obvious nod to Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) seemed to escape most commentators, in a manner that’s all too common in discussion of contemporary political documentary. While Citizenfour, like most of her films so far, might seem to be informed by the ethical and visual schemas of cinema vérité, Poitras clearly hails from the “camera-as-provocateur” side of the vérité split, rather than regarding the camera as a neutral observer. Alex Danchev’s terrific piece in the Astro Noise catalogue observes that “Poitras is her own camerawoman. Her modus operandi is disarming. Typically, she holds the camera at waist height and looks down at the viewfinder rather than hiding behind the lens.” It’s the camera that allows Poitras to be with her subjects, to be fully in the world around her.

The best vérité-makers always had a keen sense of the artifice of the whole operation, and Citizenfour was important in no small part because it showed Poitras tackling that problem head-on. So while Poitras’ work is often compared to that of her fellow Bostonian Frederick Wiseman (by Danchev, among others), it’s telling that when she participated in Montréal’s RIDM in 2012, she chose to screen two classics of American experimental cinema: Andy Warhol’s Blow Job (1963) and Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (1976). When looked at through this lens, it becomes clear how formally ambitious Poitras truly is in Citizenfour. Replete with text, voiceovers, and long, smooth takes across urban landscapes, the film’s aesthetic comes straight out of ’60s modernist art cinema—not only the Roeg and Kubrick influences Poitras name-checks in her “Berlin Journal,” but Antonioni and the American avant-garde as well.

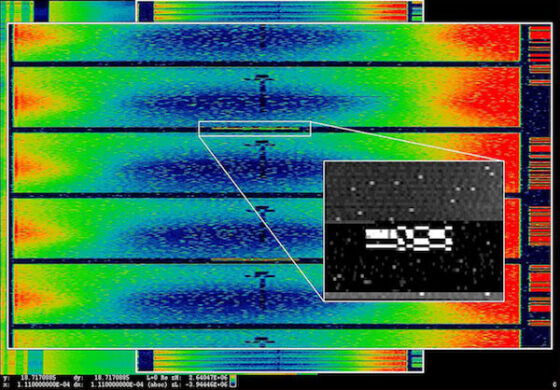

To repeat what I wrote about Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985) in these pages three years ago, Citizenfour is weird—and Astro Noise now makes it clear how much that weirdness is bound up in Poitras’ larger project. Broken into five discrete parts, the exhibition—named after the file that Snowden turned over to Poitras in that Hong Kong hotel room that contained damning evidence of mass surveillance by the NSA—welcomes visitors with a series of giant prints derived from a UK-run surveillance project based in the former colony of Cyprus called ANARCHIST which are literally impossible to read, being graphic representations of astronomical amounts of data (except for one image of an Israeli drone, which is still fairly distorted). Entering the exhibition proper, the first room is a dual projection on back-to-back screens. The first shows Poitras’ O’Say Can You See (2011), a short film made up entirely of slow-motion close-ups and medium shots of people staring at the post-9/11 Ground Zero; the other side is a dark, jumpy tape of two prisoners being interrogated in Afghanistan, one of whom is Salim Hamdan, a subject of Poitras’ The Oath (2010), which uses some of this footage as well.

The second room is an installation called Bed Down Location, which requires you to lay on your back to view footage of the nighttime skies of Yemen, Somalia, and Pakistan, and the daytime sky of Nevada, as drones lope from one edge of the frame to another. The next room is another installation, Disposition Matrix, where you look through small slits in the wall (a few of them awkwardly placed at near-ground level or absurdly high up) to gaze at NSA documents, abstract data visualisations, footage from Poitras’ 2006 film My Country, My Country, and so on. (This struck me as the least successful part of the exhibition: somewhat gimmicky in its difficulty, in the standard-issue conceptual-art manner.) The exhibition concludes with November 20, 2004, which projects Poitras’ heavily redacted FBI file on one wall, and on another the eight unedited minutes of footage shot by Poitras in Iraq that ostensibly led to the generation of that file. In her catalogue essay, Poitras recalls that after making My Country, My Country she was placed on a terrorism watch list that led to her being detained at the US border over and over again. Only when she filed a Freedom of Information request in January 2014 (the first documents of which came to her in October 2015, after she sued the government earlier that year) did she find out that this was because she was spotted filming on a rooftop after an ambush of American troops; a presumption of collusion followed. Those eight minutes—which Poitras’ voice in this part of the exhibition tells us were never viewed by anyone from the military—are utterly banal. And as that voice also tells us, they were also utterly life-changing.

On one level, then, Astro Noise is a kind of riff on Poitras’ filmography to date: we revisit some of her major characters (Snowden, The Oath’s Hamdan, My Country, My Country’s Dr. Riyadh), some of her settings (the NSA’s Utah Data Center from Citizenfour and The Program, the Yemeni capital of Sana’a from The Oath), and so on. But one important aspect of Astro Noise is the variety of video formats on display: commercial-grade digital formats, earlier HD formats favoured by turn-of-the-century doc makers, the crappy VHS favoured by US torturers and their collaborators, souped-up night-vision astrophotography footage, and indescribable drone video all make appearances here. In this, the exhibition harks back to Poitras’ early film Flag Wars (2003, co-directed with Linda Goode Bryant), a doc about gentrification in Columbus, Ohio, that—while certainly no great film—makes for interesting watching due to its mixing and matching of video formats, some of which look quite skippy and low-end (which seems to have been dictated by the limitations of shooting inside courtrooms). This visual heterogeneity complements the cavalcade of surprising and contradictory characters that Poitras and Bryant present: a patient and sympathetic bylaw judge; a warm, eccentric, mildly homophobic local activist who’s been ordained as a Yoruba priest and chief; a real-estate agent with some bad ’90s glasses whose sincere commitment to queer solidarity is rivalled by her hard-nosed business savvy.

In both style and subject, Flag Wars is a bit of a mess—and looks even more so in light of Poitras’ mature work, where the filmmaker’s steely-tight control over sound and image creates an electric tension with the world-spanning chaos that is her subject matter. While Astro Noise in some ways marks a return to the “messiness” of Flag Wars, it’s a messiness now fused with both the skill of a masterful filmmaker and the perspective of a world-weary dissident living in on-again/off-again quasi-exile. While not exactly Tarkovskian, there is something in Poitras’ work of the Slavic solemnity of the high Cold War era—something that, in its best moments, gave birth to a kind of morally inflected, politically tortured modernist practice. “Our bodies betray us. I should rewatch [Kieślowski’s] Blue, White, Red,” Poitras writes in her “Berlin Journal” for February 16, 2013; I’d have suggested she instead rewatch The Decalogue (1989), followed directly by Stalker (1979). It’s no wonder that science fiction played such an important role in that particular period of Eastern European cinema, performing certain key functions that religion (for a variety of reasons) couldn’t. The genre offered ways to talk about both the promise of technology, and the way technology could quash its own promise; about how the higher human purposes in whose service technology could be put are frustrated (if not destroyed) by those forces of authority who pervert technology into mechanisms of control. Less allegorically, there is something of this as well in the more conventionally modernist sci-fi films Poitras cites in her “Journal”: Bowie’s dissident starman wandering through an arid desert landscape in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), or the clean lines, bright colours, and sedating sterility of Kubrick’s future-tech in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which conceals the violence that that technology is capable of and supplants the promise of transcendence it is indifferent to.

In his Astro Noise catalogue essay, Snowden sees in the infinity of space a terrestrial dream of individual autonomy, the stars themselves providing the basis of a truly random, unhackable key code: “The signals we receive constitute an ever-changing key forged from the sky itself. Such a key could only be imitated by an agent listening from that exact same place, in that same direction, at that same time, to those exact same stars.” Snowden’s yearning to hear that heavenly music isn’t so different from Cornell’s: both try to listen, but are constantly confronted by the reality of the world we have built around us. Poitras is emerging as our most important chronicler of that new world, a stark, terrifying place that may now be too far gone for us to ever return from. But part of Poitras’ greatness lies in her ability to be surprised: by the grace of emerging from a tunnel in Hong Kong, or gazing up at the night sky of Sana’a, or witnessing a doctor peering across barbed wire at his imprisoned countrymen and meticulously recording their medical complaints. Like all great modernists, Poitras wants to believe in the ability of her chosen form not only to represent but to intervene in the world, even as she constantly comes up against its limitations of so doing. As the empire starts to crumble and the men without qualities shrug their shoulders and ramble about being honour-bound to defend freedom, Poitras continues to find new ways of seeing. She is still one of those who listen.

Jerry White- « Previous

- 1

- 2