Hardbodies and Soul: The Professional Wrestler as Actor

By Adam Nayman

Wrapping up the Toronto International Film Festival in Film Comment last fall, editor Gavin Smith praised Philomena and confused the Yucatan for the Philippines before bestowing his seal of approval on Oculus, a mildly effective American horror movie by Mike Flanagan about a haunted mirror. Notwithstanding Smith’s assertion that it features “the creepiest piece of furniture in movie history”—a designation that surely slights Death Bed: The Bed That Eats (1977)—the most interesting thing about Oculus is its creative imprimatur: it’s the result of a co-production arrangement between genre-meister Jason Blum and WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) Studios, which in 2006 branched out from its original mandate, which was to develop feature film properties for its contracted performers (there are no wrestlers in Oculus).

WWE Studios titles in recent years include The Condemned (2007), a likeably gruff Battle Royale (2000) rip-off starring “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, and See No Evil (2009), a Saw rip-off that typecast quasi-undead bad guy Kane (Glen Jacobs) as a reclusive psychopath picking off city kids one by one, Leatherface-style. The studio’s biggest hit, though, was The Marine (2006), a gruelingly jingoistic showcase for rapping World Champion John Cena that has already spawned two direct-to-DVD/VOD sequels. (Lazily shot yet ludicrously over the top, The Marine is basically MacGruber [2010] with a straight face; recall that the latter featured cameos from a bunch of pro wrestlers, who get blown up mere moments after being recruited by Will Forte’s black-ops specialist).

The history of the WWE’s forays into feature filmmaking actually extends back 25 years to the release of No Holds Barred (1989), back when they were the WWF (World Wrestling Federation). This star vehicle for Terry Bollea was produced under the makeshift “Shane Distribution Company” banner, named for company CEO Vince McMahon’s first-born son. Bollea had made his first major pop-cultural impact in the movies, playing the arrogant wrestler “Thunderlips” in Rocky III (1982), a wittily self-reflexive performance that allowed him to parade his world-beating “Hulk Hogan” persona while also making fun of it. Embracing The Italian Stallion at the end of their charity bout—which appears to be a “real” altercation based on Rocky’s panicked reactions to being bodyslammed and suplexed all over the ring—Thunderlips reveals that his villainous shtick is all an act: a tacit admission on behalf of the entire professional wrestling establishment.

No Holds Barred, by contrast, takes place in a world where professional wrestling is deadly serious—a universe where the fourth wall remains upright and indestructible. The feature debut of former Max Headroom director Thomas J. Wright, it’s a laughably bad movie that nevertheless functions intriguingly as a bizarro allegory for the industry that spawned it. After spurning the advances of an evil network honcho (Kurt Fuller) who wants to turn professional wrestling into a global entertainment business—basically, Vince McMahon’s actual business plan in the ’80s—Bollea’s principled heavyweight champion Rip returns to the ring to battle the hulking ex-con Zeus (Ron “Tiny” Lister), who has made his name on the real-life tough-guy circuit. Rip’s victory is emphatic—both Zeus and the television executive fall to their deaths in front of a live studio crowd—and allows him to regain his rightful place as a celebrity figurehead. (Twenty-five years later, Bollea has stayed in the spotlight by doing reality television and arm-wrestling crackhead mayors).

A modest box-office success in Hollywood’s first official “summer of sequels” (it opened against Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade), No Holds Barred did not kick-start a cycle of wrestling-themed movies. The now-defunct Atlanta-based World Championship Wrestling took their best shot with Ready to Rumble (2000), a knockabout comedy starring David Arquette and Scott Caan as a couple of knucklehead ring-rat fanboys mixed up with WCW stars, but audiences didn’t bite. Meanwhile, over in Stamford, Connecticut, the WWE was rocked by steroid scandals that forced the organization to cut salaries along with most of its extra-curricular activities. The next “WWE Film” would be 2002’s The Scorpion King, a collaboration with Universal Pictures which represented a passing of the torch: from Hogan, the company’s signature star of the “Rock n’ Wrestling” ’80s to Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, a standout of the so-called “Attitude Era.” Like Bollea, Johnson had debuted with a heelish extended cameo in The Mummy Returns (2001), where he appeared as a sneering, half-arthropodic Egyptian warlord; the original Thunderlips. The Scorpion King was quickly rushed into production to capitalize on the Miami born, Samoan-descended ex-college football star’s spiralling popularity with WWE fans, who had warmly embraced his semi-ironic “People’s Champion” gimmick.

To say that Johnson—whose performance as a deeply religious moron-turned-murderous extortionist in Michael Bay’s truth-is-stranger-than-fiction farce Pain & Gain (2013) earned him a tenth-place finish in the Village Voice’s annual Film Poll in the supporting-actor category—is the best actor of all the professional wrestlers to make the full-time transition to movies might sound like a backhanded compliment. But it’s actually a nobler lineage than it seems, filled with examples of grapplers who managed to channel the inherent drama of their main occupation into a different medium.

For instance, while casting The Shanghai Gesture in 1940, Josef von Sternberg discovered a hulking Ukrainian with a BA from a Manhattan university named Mike Mazurki, whom he cast in a bit part. From there, Mazurki would loom large in the history of American film noir, working with Edward Dmytryk in Murder, My Sweet (1944), where he played the brutish yet movingly bruised Moose Malloy (a role assumed by the gigantic boxer Jack O’Halloran in the 1975 remake), and Edmund Goulding in Nightmare Alley (1947). And, most memorably of all, he played a dangerous up-and-coming wrestler called The Strangler in Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950).

His onscreen opponent in Dassin’s film was the veteran wrestler Stanislaus Zbyszko, whom the director discovered living on a chicken farm in New Jersey. The two became friends, and Zbyszko reportedly accompanied Dassin on his outings to watch experimental theatre in London during filming. A stalwart of the Greco-Roman wrestling circuit who battled both the legendary German-American champion Frank Gotch and the towering Punjab pehlwan The Great Gama to legitimate draws in the 1910s, the old Pole reportedly echoed his character’s laments about his occupation being subsumed into show business—a conflict that plays out during his character’s clash with The Strangler. Night and the City is an uncommonly mournful thriller overall; the decision by low-level hustler Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark)—an “artist without an art,” according to one rival—to get into the fight-promoting business proves fateful and fatal. Dassin’s typically precise direction gives Night and the City some momentum despite the stalled aspirations of its protagonist, while its vision of the wrestling trade as a welter of shady setups and family feuds makes it perhaps the bleakest movie ever set in the milieu.

A few years later, Stanley Kubrick would borrow Dassin’s casting tactics for another keynote noir, employing the massive Georgian polymath Kola Kwariani to play a brawler hired by Sterling Hayden’s enterprising hood in The Killing (1956). Introduced playing chess and talking philosophy, Kwariani’s Maurice Oboukhoff is a voice of reason in a movie about panic and paranoia, which makes his subsequent eruption at a crowded racetrack, taking on all comers with a behemoth’s easy confidence, all the more memorable. The image of a bald, broad-shouldered giant calmly swapping knights and rooks with his opponent might seem like a Kubrickian conceit, but it was actually based in reality: Kwariani met the director in New York’s famed Chess and Checker Club (colloquially known as the “Flea House”) and appeared with Kubrick and Hayden on the cover of Chess Review magazine. Incredibly, Kwariani died after getting into an altercation with a gang of youths outside the Flea House in 1980; fighting solo at the age of 77, he held his own but eventually succumbed to his injuries.

The chess/wrestling intersection also figures into John Landis’ amazing An American Werewolf in London (1981), which features the late English character actor Brian Glover as a chess-playing patron at the Slaughtered Lamb pub in the film’s prologue. Before becoming a familiarly ferocious face on British television, Glover had wrestled under the assumed name of “Leon Aris, the Man From Paris,” a persona he frequently reprised on ITV’s World of Sport program. Glover acted on stage, including a stint as Charles the Wrestler in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of As You Like It, and also in movies for key UK filmmakers such as Lindsay Anderson (O Lucky Man!, 1973) and Ken Loach (Kes, 1969). His turn in Kes as a sadistic middle-school PE instructor who joins in a student soccer game to bully the younger players is a miniature masterpiece of alpha-male malevolence. (“That, boys, is how to take a penalty,” he crows after kicking the ball past one of his cowering students.)

In the ’60s, American wrestling promoters dissuaded their athletes from appearing in films or television, lest it tip off viewers to the fakery of their profession. But as wrestling began to be widely televised in the ’70s, the crossovers between the squared circle and the screen became more common. Lenny Montana, a big Brooklynite who adopted the itinerant “Zebra Kid” gimmick in the early ’50s and got paid under the table as an arsonist for the Colombo organized crime family (leading to a stint at Rikers Island), got cast by Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather (1972) as Corleone enforcer Luca Brasi. Life imitated art twice over in this case, as the otherwise unflappable Montana got so nervous at the prospect of acting opposite Marlon Brando that he relentlessly ran his lines in between takes. Amused at the spectacle of a burly tough guy fretting over dialogue, Coppola incorporated the scene into the film. Around the same time, NFL star/future Webster fixture Alex Karras, who had moonlighted as a wrestler in the early ’60s after getting suspended by the Detroit Lions for gambling, showed up in Blazing Saddles (1974), where he punched out a horse—a gag so good Arnold Schwarzenegger stole it in Conan the Barbarian (1982).

Richard Flesicher’s disappointingly tame take on the Robert E. Howard mythos in the 1984 sequel (which Roger Ebert rightly observed had seen Conan repackaged, Spielberg-style, as “your family-friendly Barbarian”) flanked Arnold with a pair of seven-footers: Wilt Chamberlain and Andre “The Giant” Roussimouff. As the horned, demonic deity Dagoth, Roussimouff was the most impressive aspect of a cut-rate production; as David Shoemaker writes in his excellent, elegaic new book on death in professional wrestling, The Squared Circle, “before CGI, there was only Andre.” Just as Roussimouff bridged the era between professional wrestling as a dispersed, territorial enterprise and its current incarnation as a multimillion-dollar business, his appearances in Conan and The Princess Bride (1987) collapsed the gap between the days of wrestlers as oversized bit players and star attractions. In the ring, Andre had frequently been cast as a monster “heel” (industry parlance for bad guy), but his unbelievable size actually endeared him to viewers; his role in The Princess Bride as Fezzik, a sweetly dim henchman who gradually realizes he’s a hero, could be taken as a microcosm of the formidable Frenchman’s entire wrestling career.

In 1987, Roussimouff would face Bollea in what was then the “biggest match of all time”: a main event bout at Wrestlemania III in the Pontiac Silverdome in front of (allegedly) 93,000 live fans. No combination could emblematize the WWF’s initial Age of Empire like Andre the Giant vs. Hulk Hogan, but the true future of wrestling—and of wrestlers in the movies—was playing out a little further down the card. Having already showed that he could read lines in Hal Needham’s Body Slam (1987)—a comic gloss on Night and the City describing a more successful wannabe wrestling promoter—Roderick George Toombs, AKA “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, starred in John Carpenter’s thriftily nifty They Live (1988) as a drifter who literally sees through an elaborate alien conspiracy to enslave humanity. “As you’d expect from one with hundreds of hours experience playing opposite other professional wrestlers in what is essentially live, semi-improvised theatre, Piper’s best in scenes [with] some other strong male presence,” writes Jonathan Lethem in his Deep Focus volume on the film. “Conveying fear and rage is in his wheelhouse.”

This is true enough: in his day job, Toombs played the role of the nervy, easily riled Celtic madman to the hilt. Yet as Lethem hints later, the casting of Piper is brilliant in a way that transcends any actorly particulars: “unlike real actors, who willingly take off their disguises and discuss the secrets of their craft, professional wrestlers—like They Live’s ghouls—will never admit their deception except amongst themselves.” Elsewhere, Lethem name-checks noted wrestling fan Roland Barthes’ Mythologies in his deconstruction of They Live, noting that both philosopher and film exult in “the giddy thrill of unmasking what may from some vantages be regarded as howlingly obvious, yet goes by common consent unspoken.” Piper made his name at a time when the reality of professional wrestling was precisely this sort of open yet closely guarded secret, until the advent of the internet afforded “smart” fans an easily accessible equivalent of Carpenter’s famous Hoffman lenses: a technological means to definitively see through the charade and recognize the object of their affections for the highly choreographed, increasingly branded spectacle that it truly was.

They Live ends on a mock-triumphant note with the invading aliens unmasked to the world at large via television broadcast; Carpenter cuts the film off before we can see if the viewership will take this revelation as a cue to revolt or simply accept the new reality as “extreme” programming. The ’90s were the WWE’s They Live decade, as McMahon and his cronies began to blur the line between “kayfabe”—the scripted, scrupulously controlled reality of pro wrestling since time immemorial—and chaos, first inadvertently in the famous “Montreal Screwjob” that saw Canadian champion Bret Hart deposed via actual behind-the-scenes machinations that were subsequently reported in the mainstream media, and then determinedly in a series of programming choices that fairly dared audiences to spot the slippage between actuality and drama. This newly in-between state re-energized an art form that had previously organized itself around binaries of “fake” and “real,” and the blurred lines were good for business.

The new perspective of 21st-century professional wrestling underwrites a number of notable films, including Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler (2008), which takes potshots at the No Holds Barred era via the vaguely Terry Bollea-esque character of Randy “The Ram” Robinson (Mickey Rourke), a ruined relic of the kayfabe days. (If Randy is a Hulk Hogan manqué, then his old pal/nemesis “The Ayatollah,” played by ex-WCW mid-carder Ernest “The Cat” Miller, nods in the direction of The Iron Sheik, a Persian villain now reborn in his 70s as a Twitter superstar). Perhaps the best of Aronofsky’s films, The Wrestler highlights a second dichotomy in the world of professional wrestling—the separation between the “major” federations and the independents. This minor-league ethos is the subject of Robert Greene’s superb and superior nonfiction film Fake It So Real (2012), an account of underpaid North Carolinian grapplers perfecting their DIY routines that Richard Brody suggestively framed as a metaphor for the depressed economics of microbudget filmmaking.

“About the best we can hope for is 20 bucks, a hotdog, and a pat on the ass,” carps one of Greene’s subjects, illuminating the reality of toiling in the trenches of a competitive profession, far removed from stadium sellouts and pay-per-view payoffs. And yet, as David Shoemaker makes painfully clear in The Squared Circle, more often than not, the most iconic, internationally recognized professional wrestlers end up right back on the margins, and not only because their job is no country for old men: of all the occupational hazards wrestling brings with it, drug abuse—starting with steroids and moving up the scale to painkillers and worse—is the most prevalent.

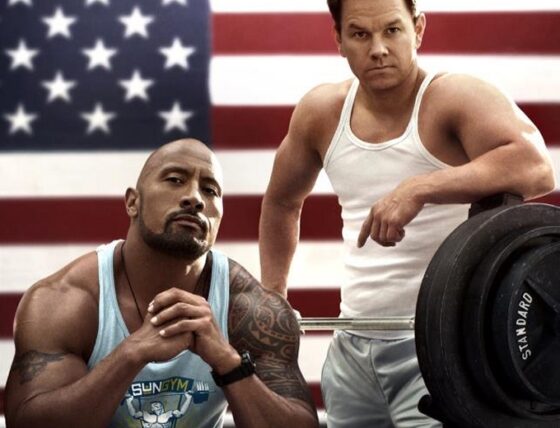

This grim trend of wrestlers turned addicts places Dwayne Johnson’s remarkable work in Pain & Gain in startling relief. His Paul Doyle is a gym rat with an addictive personality, mainlining Christian platitudes and physical fitness to keep his desires in line, but he’s led into temptation by Mark Wahlberg’s avaricious personal trainer Daniel, whose desire to open his own chain of gyms with ill-gotten gains echoes Harry Fabian in Night and the City. Johnson is slightly more aerodynamic now than when he butted heads with Seann William Scott in Peter Berg’s only good film, The Rundown (2004), but he’s still humorously huge and performs the character’s inevitable (back)slide into bad behaviour with proportionate aplomb. Suddenly flush with cash after Daniel’s plan goes semi-right, Doyle proceeds to blow most of it on blow; when his previously becalmed comportment cracks and crumbles into the hysterical body language of a man desecrating his own self-erected temple, it’s hilarious and startling.

Johnson’s wrestling stardom was predicated on the post-kayfabe recognition of his own ridiculousness: decked out in gaudy suits and sunglasses, shamelessly spouting catchphrases in between boasts, the character nodded to Thunderlips et al while raising one skeptical eyebrow at the entire show. That same self-awareness pervaded Johnson’s performances in kiddie flicks (The Tooth Fairy, 2010) and auteur works (Southland Tales, 2006) alike, but in Pain & Gain he touches on comic genius by inhabiting Doyle’s perplexed anguish rather than mocking it. He’s a straight arrow bent so grotesquely out of shape as to become (lethally) weaponized, and while Michael Bay’s oddly Coenesque comedy is hardly an exercise in empathy—for its characters or its audience, which it all but piledrives into submission—one wonders if Johnson isn’t in some way pouring one out for all his predecessors and peers consumed by their appetites. At the same time, his indelible acting in a movie with its share of critical champions will hopefully serve to remove some of the stigma from the history of wrestlers-turned-actors—a minor but refreshingly unpremeditated victory.

Adam Nayman- « Previous

- 1

- 2