Ghost Operas: Music from the Films of Bertrand Bonello

By Sean Rogers

“I think that to write the music for that scene was also his way to tell it…You almost have the impression that his script for the scene is the colour and the sound, that’s it.” Bertrand Bonello is here referring to a scene from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), in which the doomed Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) sways to a sinister, druggy rhythm on a roadhouse dance floor bathed in red light. The bar band is playing Lynch’s own composition “The Pink Room” (one of the few Twin Peaks tracks not written primarily by Angelo Badalamenti), and the imposingly bassy and tremolo-soaked performance overwhelms every other element of the soundtrack. It’s like a glimpse into Laura’s haunted soul: there seems only to be that throbbing song, and that infernal light. “[Lynch is] truly a filmmaker who has found his own sound,” Bonello continues, “and he’s found it all alone.”

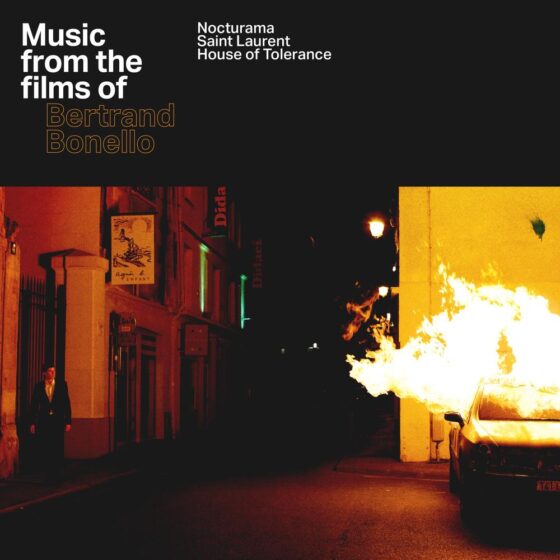

With Grasshopper Film’s limited-edition release of Music from the Films of Bertrand Bonello, we are now better able to assess to what degree Bonello himself has found his own sound. “Music is there as soon as I start working on the script, from the very first,” says Bonello, who was a musician before he was a filmmaker (he’s done session work for Françoise Hardy, among others). That primacy is clear in his films, whose most memorable set pieces are accompanied by startling, left-field pop-music cues: the brothel workers slow-dancing teary-eyed to The Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin” in L’Apollonide: Souvenirs de la maison close (2011); in Saint Laurent (2014), the designer’s model and muse Betty Catroux (Aymeline Valade) whipping her hair back and forth to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “I Put a Spell on You”; or, well, Willow Smith’s enervating “Whip My Hair” used to score scenes of explosive carnage in Nocturama (2016).

What we can now better appreciate thanks to the new Grasshopper LP (all of whose tracks are drawn from these three films) is how Bonello’s curatorial ear has overshadowed his own compositions, which burble away in the background of his films and quietly create their doomy, crepuscular moods. One might not have previously registered how “Nocturama,” its muffled beat chugging along with an inescapable drive, ties together that film’s widely dispersed opening scenes, prolonging the suspense almost interminably; or the way that chaos and melancholy are inscribed in the staccato pulses that form the melody of “Yves,” the album’s closer and stand-out. (Saint Laurent occupies all of side B, presenting a sequence of songs coherent, adventurous, and aching enough to make a strong argument for that overlooked film’s reappraisal.)

Though Bonello’s music is sometimes quite frantic (e.g., the syncopated cymbals and coked-out clusters of melody in “Jacques de Bascher,” the theme for Saint Laurent’s diabolical paramour), it predominantly tends toward the steely, synth-heavy, and subdued, especially in the more droning, atonal cuts from L’Apollonide. It is minimalist, sleek, black as obsidian—“a colder side of the musical aspect,” as Bonello puts it, in contrast to the warmth of his pop cues. But is this Bonello’s own sound, in the same way “The Pink Room” is Lynch’s? There are definite, pronounced traces on the LP of some of Bonello’s acknowledged influences. There is Lynch (and Badalamenti), of course, in the sultry slow burn of “Vision de Nuit,” its ominous fuzz hovering just this side of haunting melody; there is the self-conscious, almost cartoony creature-feature prog rock of Goblin’s soundtrack to Dawn of the Dead (1978); there’s the slick, downtempo electro of Giorgio Moroder (whose whispered, creepy cover version of “Knights [sic] in White Satin” I hear everywhere in Bonello); and there’s the blunt synths and curt percussion of the theme from John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976).

Bonello is not simply paying homage to these musical touchstones, however. Expanding upon the decades-old sonic ideas of one-time cutting-edge innovators such as Moroder, Tangerine Dream, and Kraftwerk, his music is closer to what critic and theorist Mark Fisher calls a “nostalgia for the future.” I’ve been reading Fisher’s newly published, posthumous book, K-punk: The Collected and Unfinished Writings of Mark Fisher, at the same time I’ve been listening to Bonello, and finding rough parallels between the filmmaker’s work and Fisher’s elaboration of the Derridean concept of “hauntology,” which the author defines as “lost futures, of things which never happened but which could have.” For Fisher, the exemplary hauntological recording artist is the British electronic musician William Emmanuel Bevan, better known as Burial (who, incidentally, sampled Lynch’s Inland Empire [2006] for the opening of his 2007 album Untrue, and whose 2016 track “Nightmarket” sounds like a lost Carpenter theme). Burial’s music, writes Fisher, exhibits “a craving for a past which nevertheless appears irretrievably lost, veiled behind a relentless drizzle of crackle. Beyond the longing for a particular moment or a particular musical genre is a longing for the ceaseless forward motion of a culture which once appeared capable of endless renewal, but which is now used up, involuted.” Bonello’s compositions don’t crackle or foreground their artifice enough to match Fisher’s concept exactly, but this is certainly what Bonello’s films mourn in their melancholic evocations of the Belle Époque, ’70s haute couture, and affectless, impotent youth rebellion in the present: the foreclosure of possibility, the exhaustion of a culture’s vitality.

Bonello’s isn’t the only recent movie music to be haunted by the past, or by what Fisher calls “the spectres of lost possibilities.” For Good Time (2017), Warp Records signee Oneohtrix Point Never (a.k.a. Daniel Lopatin) complements the Safdie brothers’ grungy ’70s crime-movie aesthetic with a frenetic, wall-to-wall electronic soundscape that replicates the desperate fugue state of Robert Pattinson’s petty grifter, leaning on a retro-futurist synthesizer sound quite similar to Bonello’s. The score for Phantom Thread (2017) by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, meanwhile, swells with huge orchestral arrangements and soaring strings that would suit the echt-romantic style of classical Hollywood composers such as Franz Waxman or Max Steiner were they not so frequently, eerily dissonant. And for Mandy, the late 4AD and Deutsche Grammophon artist Jóhann Jóhannsson figures the film’s yearning for both a disappeared girlfriend and for a fetishized recollection of the ’80s with a kind of feature-length, slow-motion imitation of the Mercyful Fate discography, draping the movie’s self-consciously heightened sentiments of love, loss, and vengeance in none-more-black cloaks of sludgy guitar noise, prettily mathematical noodling, heavy reverb and ambient hiss. Metal is also the driving force of French musician Igorrr’s (né Gautier Serre) score for Bruno Dumont’s Jeannette: L’enfance de Jeanne d’Arc (2016), another film that excavates the past in order to find what hope we have lost—though despite its head-banging bona fides, the soundtrack is often disarmingly un-metal, plodding when it could be shredding, and opting for Sprechstimme when there could be shrieks. (Serre characterizes his practice, as well as Dumont’s, as “a contrast of extremes”—a way of reconciling the past with the present by mining finicky Baroque compositions as much as, say, Burzum.)

While Greenwood, Jóhannsson, Lopatin, and Igorrr began as recording artists and wrote directly for films only later, John Carpenter followed the opposite trajectory. Along with Bonello, Lynch, and a select company of others (Clint Eastwood, Jim Jarmusch, Boots Riley), Carpenter is one of the few contemporary filmmakers who has also written music for his own films—even though, in recent decades, his soundtracks have lacked visual accompaniment. Carpenter hadn’t made a theatrical feature since the workaday The Ward in 2010, and hadn’t scored one since his gung-ho gong show Ghosts of Mars in 2001, when he released his first Lost Themes album on Sacred Bones Records in 2015. This work, and its 2016 sequel, seemed to channel a decade-plus of pent-up creative energy, conjuring movies in the mind solely on the basis of suggestive titles—“Wraith,” “Purgatory,” “Last Sunrise,” “Utopian Facade”—and the moody, monochromatic, minor-key minimalism Carpenter helped pioneer. Here were all the Carpenter movies we once thought we might see but which never materialized: imaginary soundtracks to phantom films, music haunted by the ghosts of what might have been.

While Bonello has been far more cinematically active than Carpenter over the past decade, he too has experimented in this phantasmal arena, circling projects that refuse to come into being. In 2014, his exhibition Films fantômes at the Centre Pompidou presented a catalogue of these abandoned films, including La mort de Laurie Markovitch (named for the musical group with which he recorded his earliest soundtracks) and Madeleine d’entre les morts, a would-be prequel to Vertigo (1958) that makes a fleeting appearance in Le dos rouge (2014), in which Bonello plays a director struggling to get his next project off the ground (and for which he also composed the soundtrack).

Bonello’s most striking “ghost film,” however, is one that has actually been produced—though it concerns the rehearsals for an “opera that will never be performed,” according to one character’s portentous pronouncement, “because it does not exist.” Produced under the aegis of the Opéra national de Paris, the 2016 short Sarah Winchester, opéra fantôme pairs Bonello’s pulsing synth compositions with a wailing lament for chorus composed by French pop scorer Robin Coudert (a.k.a. Rob) to tie together disparate strands of action. In the first of these (phantom) threads, a Bonello-like composer-director (Reda Kateb) stands self-involved at his Mac, keyboard, and audio console in the pit of the sleekly modern Opéra Bastille, lurching repeatedly into a lugubrious, digitized musical performance. In another, onscreen text, unnervingly half-finished drawings, and Kateb’s halting monologue tell the story of Sarah Winchester, the widow of firearms tycoon William Wirt Winchester, who reputedly built the sprawling Winchester Mystery House mansion with her late husband’s fortune in order to house the wandering spirits of those killed by his products during the Civil War. Then, on stage at the Opéra Garnier, a dancer (Marie-Agnes Gillot) in body stocking, tutu, and slippers, convulses her way through a solo interpreting Sarah’s predicament, apparently at Kateb’s direction, while in a studio the opera chorus performs a threnody by the voices of the dead that haunt Sarah. Finally, a child (perhaps a manifestation of Sarah’s daughter Anne, who perished in infancy) silently wanders the wings of both Opéra houses, barefoot in a shift, dripping blood.

Bonello forces connections between these diverse spaces and situations both through visual means (cross-cutting and eyeline matches that make it seem as if Kateb and Gillot are conversing, even though each remains isolated at separate locations of the Opéra) and through music: so that Kateb’s sombre electronica underscores the chorus’ ghostly keening, so that Gillot seems to be vibrating along to both strains of music, and so that the child seems summoned as though by a ritual performance. As in the opening scenes of Nocturama, music here serves as connective tissue, yoking together and creating resonances between elements that would never otherwise echo each other. The most profound connection that is forced here, however, is not that between scenes, or that between image and spectator, but that between living and dead: between a past we have forgotten and a future we never knew, between the old Garnier and the new Bastille, between the human voice and the mechanical drone of the synthesizer, between the mourning Sarah and the ghost of Anne, or even between the long-dead Sarah and the seemingly obsessed Bonello (“I love you, Sarah,” Kateb intones offscreen at the film’s close). For Bonello, just as for Carpenter, Jóhannsson, Lynch et al., music has the capacity to conjure the beloved dead, to resurrect the ghost of an idea. This music, like the opera, is haunted.

Sean Rogers