Garden Against the Machine: Ja’Tovia Gary’s The Giverny Document

By Michael Sicinski

Ja’Tovia Gary’s filmmaking is all to some extent grappling with the question of identity, particularly its precariousness in an often hostile world. Early films such as Cakes Da Killa: No Homo (2013) and An Ecstatic Experience (2015) explore the complex histories of African-American life, in particular the role of art and storytelling in establishing stable identities across time. But her latest film is itself possessed of a somewhat mutable, even uncertain identity. The official title of the film is The Giverny Document (Single Channel), which seems to imply that at some future point, The Giverny Document may be reconfigured for a multi-channel gallery installation. This has not happened yet, and I’d be curious to see what such a reorganization of the material might add to the fundamental power of the Giverny material.

After all, The Giverny Document (Single Channel) has, at its core, a re-edited, expanded version of the material from Gary’s previous film, Giverny I (Négresse Impériale) (2017). In fact, much of that original film appears in its original order within The Giverny Document, with one significant new element added into the mix. In light of this, an additional remix of the Giverny project, with additional monitors and sequencing, could very well allow Gary to introduce new threads of inquiry into the piece which, for formal or narrative reasons, could not fit easily into the flow of the single, linear, 43-minute film. One could imagine Giverny becoming a long-term, multimedia project for Gary, along the lines of Apichatpong’s Primitive series, which also contained short films, features, and museum installations.

Were Gary to adopt this approach, it would stand to reason in some sense, because the two Giverny films are themselves dense collage works that not only draw together several different aural and visual forms but also work to articulate connections between radically different cultural traditions and historical/political formations. This is a tendency that has been implicit in Gary’s work up to this point, but Giverny explores it with a new fluency and expansiveness. At issue throughout her work has been the question of identity, but in particular the historical and political dimensions of that issue. In short, what are the social forces that marginalized African-American bodies, in particular the bodies of African-American women? How have African-Americans been made into objects of modernism, rather than full heirs of modernity? And can art be a space for the reclamation of African-American subjectivity, even as the broader social world ramps up its white supremacist tyranny?

Both Giverny films have the same pictorial “base,” a primary material into which other filmic sources are integrated. Gary went to the gardens at Giverny, France, a location immortalized by the paintings of Claude Monet. We see the stunning green walls of foliage, close-ups of bright flowers, and the walking bridge featured in one of Monet’s most famous Giverny canvases. But within this landscape, we see Gary herself, sometimes walking, sometimes standing within these latter-day digital-video “paintings.” Both the maker and the model for these renewed versions of Monet’s vision, Gary gently but firmly asserts the black woman’s presence within this canonical space, her contemporary as well as her historical right to be there. A curvy woman in a loose fitting floral-print dress, Gary also seems to allude to a wider history of painting: Gauguin’s Tahitian women, the two figures of Manet’s Olympia, or the various women in nature favoured by Auguste Renoir.

But Gary’s presence takes the form of a historical fort/da game. She speaks just as forcefully about her absence from this official history, her body occasionally disappearing and reappearing in the form of a “glitch.” This digital glitch is the dominant aesthetic feature of this portion of Giverny, as images pop in and out with an electronic chirping sound, creating an affective jolt for the viewer. Gary is layering various images and sounds, but not seamlessly. She wants us to perceive the action of her interventions, to see the labour necessary to “invade” this garden space.

Along with an audio track composed by Norvis Jr. that loops and processes the voice and trumpet of Louis Armstrong into a kind of screwed-and-chopped lament, Giverny disrupts the garden footage with archival scenes of Monet painting, and excerpts from a talk by Fred Hampton in which he states that “if the people ain’t educated, one day we’ll have Negro imperialists.” Hampton is speaking of African-Americans who, gaining a certain amount of power, would sell others out and betray the cause of Black Liberation. However, Gary turns this idea on its head. Calling her short film Négresse Impériale, she implies that she is the “imperialist,” coming into the heart of the white Western canon to claim it as her own.

This can be seen most clearly in terms of the other ideas and materials Gary brings with her into the Monet Garden. This section of Giverny is rhythmically punctuated by passages of leaves and plant matter in extreme close-up, travelling upward through the projector gate. Gary’s homage to Stan Brakhage and Mothlight (1963) is unmistakable, and seems to function in several ways. It provides a micro-view to contrast with the expanse of the gardens themselves. It also offers a comparison between the living (Giverny) and the dead (the plant matter pressed onto celluloid). But perhaps more than this, it is another instance of Gary positioning herself with respect to the official white canon. As an experimental filmmaker, Gary has every right, and undoubtedly a need, to lay claim to the tradition, and while that tradition is as much hers as anyone else’s, she must also find her own place within it as an African-American woman.

But the garden is a clearing, a world apart. Appropriating it as a space for black women’s existence is important, just as “imperializing” the rarefied realm of the aesthetic is an important gesture. But as Gary demonstrates in Giverny, the broader world—the “outside” that is not carefully manicured and protected—is a war zone for black bodies. As we see Gary in Monet’s garden, with the Brakhage-style foliage clicking by, this abstracted space is forcefully disrupted by the larger world. Glitching in and out of the flow of information, we see and hear Diamond Reynolds’ video of the murder of her boyfriend Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota by Officer Jeronimo Yanez. We hear her anguished cries, her pleas with Yanez, and her fear for the life of her four-year-old daughter.

Near the end of this sequence, and the original Giverny I, Gary is screaming in rage while standing on the Monet bridge. The freedom, safety, and mythical innocence of the garden is revealed to be an illusion. Gary’s intermixing of these various strands of information have made this clear from the start. At any given time, a base image is crossed by a series of thin stripes showing the movement from another image, as if someone had scratched the “paint” off the initial scene to reveal the palimpsest underneath. And at other times, Gary layers images within images, bisecting the garden scenes with the Brakhage material, or the Castile shooting. Every space depicted is hybridized from the start.

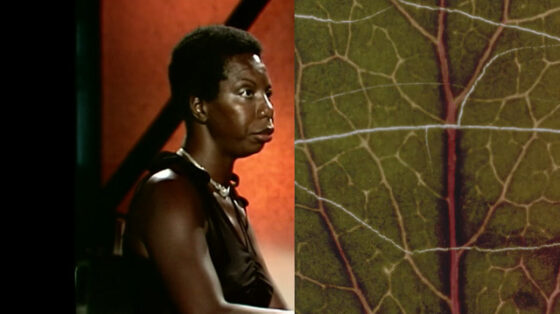

One major difference in this section between Négresse Impériale and The Giverny Document is the introduction of one more thread of information, and it further complicates Gary’s implicit theme of African-American appropriation of white artistic traditions. Whereas Gary’s use of Monet and Brakhage appears to be reasonably straight-faced, this new material is astonishing in its satirical bite. We see multiple excerpts from the end of a live performance by Nina Simone, holding forth at the piano with absolute charismatic authority. However, as her last song, she is playing a deconstructive rendition of Morris Albert’s ’70s adult contemporary radio hit “Feelings.”

Simone first starts the song with a look of confusion, as if even she cannot believe she’s going to perform it. Then, she pauses to introduce her conceptual plan, saying, “As a robot gets herself together, and we do it, and we get to the mid-dle, where we have for-got-ten our fee-lings of love, you will help me?” As part of this strategy, Simone mocks the famous “whoa-whoa-whoa” chorus with a disaffected Sprechstimme. And at the same time, she slays on the keyboard, infusing the song with jazz runs and classical flourishes that its composers could only dream of. But before she gets too far into the number, Simone lays it on the line. “Goddamn. What a shame to have to write a song like that…I don’t mean to make the songwriter mad. I do not believe the conditions that produced a situation that demanded a song like that.” The audience, who obviously did not expect an evening of anti-colonialist dialectic, is stunned into silence, to which Simone replies, “Come on, clap! What’s wrong with you?”

This is the extent of the segment of Giverny Document that overlaps with the earlier Négresse Impériale version. The rest of Giverny Document, which enfolds this section both parenthetically and at various intersections, consists of something very different. We see Gary in winter clothes on a street corner in Harlem with a small documentary camera crew. She is stopping black women and girls as they go by, asking them to answer a seemingly simple question: Do they feel safe, in their bodies, in their communities, and in the world?

The answers are quite varied. While several younger women explain that they do not feel particularly safe in the world, and are very aware of being potential targets of racial and sexual violence, a number of middle-aged and elderly women express a more general sense of wellbeing, in some cases supported by their relationships with God. One young girl says she feels safe, and does not yet seem to have experienced the conditions that might make her feel otherwise. Women from Jamaica and Sierra Leone say that their experiences in America have made them feel less safe than they did in their countries of birth.

But what is really fascinating about these interview segments is the unexpected contrast they introduce into The Giverny Document. While the Monet Garden is piercingly verdant, the cityscape of Harlem in brown and grey, and this footage strongly conveys the “realism” of the documentary mode in a way that throws the heightened aestheticism of much of the rest of the film into high relief. In a way, Gary is clarifying her project by bringing her filmmaking out of the confines of the garden and into the street, to understand what is at stake for black women and their phenomenological existence, in the broader arena of social relations.

The aesthetic mode, then, can be thought of as a laboratory for exploring states of being that may then be subjected to reality-testing. Gary’s assertion of her place within an artistic tradition that has been overwhelmingly white and male is, among other things, a way to seize the means of both production and expression. In Giverny, she quite literally places herself within the picture. This is a “safe space,” but a hard-won space all the same. In taking to the streets of Harlem and speaking to other women, Gary is broadening that space, giving voice to people she encounters while at the same time acknowledging that the rarefied preserve of the aesthetic is inadequate in itself for making a lasting space of social justice. We have already seen this with Reynolds’ video of the Castile killing, or in a much less tragic way, in Simone’s performance. Art and politics are always permeable regimes.

Gary bookends The Giverny Document with found footage that features painting directly on the filmstrip. This includes an opening and closing theme, with a woman singing gospel: “I can’t lose with the help I got.” The washed-out footage includes aerial shots of sandbars in the ocean, along with rolling waves. The lively painted animations include a canoe, an anchor, stars, stripes, polka dots, and various other moving patters, recalling a less precise version of Norman McLaren’s dancing doodles. The vastness of the ocean is combined with the intimacy of a sketchbook, the combinatory immediacy of bricolage. If there is one overriding impression one takes away from The Giverny Document, it is Gary’s insistence that making the world not just a safe but a joyful place for black women is going to take every resource available. But I’m inclined to agree that she can’t lose.

Michael Sicinski- « Previous

- 1

- 2