First Person Plural: On Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind

By Phil Coldiron

“May he not be knave, fool, and genius altogether?” —Herman Melville, The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade

It begins with a death, of course, the first of the many quotations, slips, and rhymes coursing through The Other Side of the Wind, now finally arrived, more than 50 years after word of its conception first entered public circulation, in a saleable form, if not a definitive one. Though I must defer the work of surveying the distance between the film which enters the market bearing this title and the film its ghostly author, Orson Welles, would have signed his name to had history unfolded otherwise, the matter of intent, of authorship, of the director as auteur, is integral to its present coherence, and so cannot be avoided as an internal concern. This is to say that a foundational rhyme between the film now given to us and its more-than-50-year production history is inevitable; any comment on material relating to one half of this equation necessarily bears on the other. And if it is not the hidden masterpiece promised by those desperate to see its completion, the disorientation one feels in the presence of this endless series of mirrorings marks it as a perfectly Wellesian object, the richest figuration of the concept of its author as an ideological challenge.

What one sees first is, in fact, not the terminal image which traces a line through Mr. Arkadin (1955), Othello (19510, and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) back to the wellspring of Citizen Kane (1941), but a scroll of didactic text which concludes, “Welles died in 1985, leaving behind nearly 100 hours of footage, a workprint consisting of assemblies and a few edited scenes, annotated scripts, memos, thoughts, and directives. This film is an attempt to honor and complete his vision.” This text bears no signature, and the film itself bears only that of Welles (and Oja Kodar, who shares a writing credit), but we might assume that it has been signed in invisible ink by Peter Bogdanovich, who saw the projection to completion alongside Frank Marshall, and whose voice appears immediately afterwards on the soundtrack, delivering narration intended to be spoken by Welles himself: “That’s the car. What was left of it after the accident, if it was an accident…” I do not begin here out of any interest in raising long-settled concerns regarding Welles’ own capacity for completing his projects, nor should I care to draw up an actuarial table assigning value or responsibility to any particular individual; I am confident that the historians will have their day of sorting through the latter, while the former should be left in cold storage indefinitely. I begin here because, more acutely than any other work attached to Welles, The Other Side of the Wind is built, in form and content, of thrown voices, feints, false fronts, and tall tales leading to and from Welles’ idea of himself as a public figure, as the performance of a lifetime, drawn at maximum clarity then cracked apart and squirreled within shadows of such depth as to permit only flashes, glimpses, and whispers of that self image. To be a wreck is, it seems, a certain sort of freedom.

But the film is not a wreck. Its story is as simple as any in Welles’ career: Jake Hannaford, an aged titan of the American cinema, has returned after an absence from Hollywood with a chest full of European ideas about filmmaking and set to work on a comeback feature intended to settle the question of his artistic relevance. The Other Side of the Wind, which is also the title of Hannaford’s film within the film, follows the last hours of his life. Its narrative is divided into three sections: the first introduces the main characters as they circulate around the studio lot and make their way to a party being given for Hannaford’s 70th birthday; the second, and by far the longest, takes place entirely within the party; and the third concludes the failed party at a nearby drive-in movie theatre. Each of these sections is itself divided between two formally distinct tracks, the vérité-style documentation produced by the guests of Hannaford’s party and Hannaford’s film itself, seen as it is shown to both a money man (in the first section; his only response is to decline an invitation to the party) and the revellers (two long segments in the party sequence, both interrupted by failures of electricity, which prompt the final move to the drive-in).

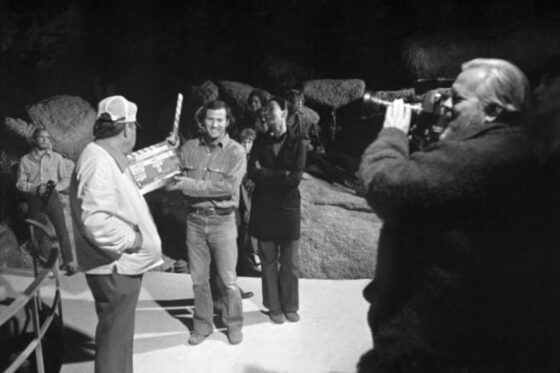

Readers familiar with the details of Welles’ life may see even in this quick sketch a number of connections with the director’s own situation at the time. To these, one might add that Hannaford is played by Welles’ longtime friend John Huston (whose late-career turn to acting is the negative image of Welles’ absence here, the only completed film of his career in which he does not appear in any capacity on either screen or soundtrack) and that chief among the guests is one Brooks Otterlake, a rapidly ascending director played by Bogdanovich, who Hannaford is in the end reduced to begging for funds for his film. (During the years The Other Side of the Wind was in production, Bogdanovich penned defenses of Welles for Esquire and The New York Times in response to perceived attacks by Pauline Kael and Charles Higham.) The rest of the guest list is filled by denizens of Hollywoods Old and New, in almost every instance playing characters derived directly from their public personas, whether in roles that made their careers (Paul Stewart, Mercedes McCambridge) or promised them (the critic and historian Joseph McBride, the directors Henry Jaglom and Paul Mazursky). This context of contrived transparency—documentary-style images of a party filled with people who might well have ended up at the same parties circa 1970, gathered to watch a film which does and does not exist, made by a director (Hannaford) cobbled together from the lives of Huston and Welles, but also Hemingway and the journeyman director Rex Ingram—does nothing to resolve the polemical positions staked out by Welles’ detractors, who found his real presence to be false (e.g., Kael’s claim, conclusively disproven by Robert Carrington, that Welles did not contribute in any meaningful way to the script of Kane), and his supporters, who found his presence so vast and powerful as to be analogous with the films themselves: “Every Welles film is designed around the massive presence of the artist as autobiographer.”

Rather, The Other Side of the Wind sustains the tension between these two poles, accruing images into an object “without ‘truths’,” because it is all true: for Welles, as for many of the most sophisticated artists of his generation, a work of art’s only source of verification is itself. Here, without any recourse to kitsch psychology (the lonely boy genius abandoned, searching for social fulfillment and desperately afraid of loneliness, etc.), we find the basis of the defining scene of Welles’ career, one which occurs in nearly every film, often more than once, and one which receives its most thorough treatment in The Other Side of the Wind: the party. Citizen Kane matches an early scene of celebration of the rise of the Inquirer with the crucial later scene of the failed party, the long shot in which Kane and Leland square off in the deep space of the empty office. The mutilation at the hands of RKO’s executives of the grand ball in The Magnificent Ambersons, still an enormous feat of mechanics even in its compromised form, is perhaps the ideal symbol of Welles’ entire career. There is the wedding dinner from which a groom briefly departs to commit murder in The Stranger (19460; the masked ball in Mr. Arkadin; the ludicrously decadent tropical “picnic” in The Lady from Shanghai (1947); the near constant state of entertaining of F for Fake (1973). A filmed party exists in a unique state among cinematic subjects, the state I referred to as contrived transparency: to convincingly film a party, one must, in a sense at least, actually throw a party. The early catastrophe of his work in Brazil on It’s All True (1993), in which Welles was accused by both the press and his producers of partying in Rio rather than working on his film—accusations which destroyed The Magnificent Ambersons and played no small role in his lifelong estrangement from Hollywood—is perhaps as clear an example of the profound misunderstanding Welles was met with from the beginning of his career. His partying was never frivolous, even when it was.

Here, it may be useful to consider Welles’ fondness for hosting in light of an artist whose name is found on the initial guest list for The Other Side of the Wind, but who was unfortunately unable to attend—Andy Warhol. I am not the first to bring these two together: Gary Indiana dreams of little Andy listening to Welles on the radio as a child, the Campbell Playhouse years in particular, and somewhat curiously, given Welles’ torment at the end of corporations for much of his life, finds their overlap in a tin can he calls “the merger of corporatism with art”; more germane to the present discussion is J. Hoberman’s assertion, made several times over the last decade (initially, I believe, in the London Review of Books) that Welles and Warhol were two of the earliest major figures of American art to take “the media” itself as their medium, rather than any specific practice. I would like to venture a third point of contact which The Other Side of the Wind confirms: that the ideal for both artists was the creation of a social context which, once set in motion, would sustain the production of an indefinite, potentially infinite, amount of art bearing their signature. Put more simply, they desired to create a party-machine that they could wield as if it were a brush or a camera. (Both realized this only fleetingly, if they realized it at all; for Warhol, it is the prime years of his film production, 1963-66, for Welles, the period from 1970-76 when The Other Side was in staccato production.) Warhol, fashionably awkward and a more accommodating host, needed only one camera, which could fit in any corner or closet; anyone who showed up could sit before it, and because they had come to his party, something would happen to them that could never happen anywhere else; they were not unique, but what they were doing at that moment was. Welles, in less abashed possession of an ego of similarly gargantuan dimensions and more insistent that everyone join in on the fun, in contrast asked that each guest (I am exaggerating here, though only slightly) pick up a camera and contribute to the communal creation of a work whose content was a portrait of some grand figure, and whose form was a portrait of everyone who sustained their position, often at considerable material or emotional cost.

This material, a collage of 8mm, 16mm, and occasionally 35mm images shot in both monochrome and colour on who knows how many cameras over the course of six years of filming, provides The Other Side of the Wind with its reckless momentum, a speeding towards catastrophe that links it most directly with Gimme Shelter (1970), and its texture of a reflexively shaped reality, a sensibility it shares with Jean Rouch (Les maîtres fous [1955] would perhaps be a more felicitous title than the bad poetry it currently bears). In contrast to the quick descent charted by this track is the excruciating widescreen tedium of the other The Other Side of the Wind, an apparent parody of Antonioni’s English-language films in particular and the era’s tendency towards crude sensuality and symbolism more generally. Welles described this “film,” in which a nameless and often naked pair played by Kodar and Bob Random tail one another through various arty locales (a rock club, the desert, an empty studio set), as “directing with a mask on,” and it contains by some measure the most cynical images of his career: they are as vicious in the clarity with which they conceive the vacuity of such filmmaking as they are opportunistic in their hope that the dumb facts of sex and mysticism would sell to a burned-out audience. (This audience would at least have been rewarded for their patience with a remarkable sequence involving the pair fucking in a moving car, seen in the harsh reds and greens of stoplights splashed on a rainy windshield, and set to the beat of its wipers, whose sheer decadence is no less idiotic than what surrounds it, but whose fusion of rhythm and colour matches the best of the era’s rock films for psychedelic kicks.) The sight of Random’s John Dale sprinting away naked from a moment of boneheaded sexual ritual and right off the set—a rebel with a more than reasonable cause—as Hannaford’s voice is heard offscreen demanding that the cameras keep rolling, marks a fitting end to a particular conception of art filmmaking.

Dale’s departure is not, or at least not solely, his acting out of aesthetic good sense. As a collective portrait of Hannaford, the heaviest line is drawn by the film-critic character, Julie Rich (Susan Strasberg)—as harsh a parody of Kael and Highham types as Hannaford’s Other Side is of the arthouse—who gradually spins out a theory that the director’s habit of bedding his leading men’s women is nothing other this his own symbolic acting out of his frustrated homosexuality. Welles, in the Maysles’ short Orson Welles in Spain (1966), a preliminary sketch of his earliest conception of what would become The Other Side of the Wind, describes making a film “against he-men.” And here, alongside the various moments of extreme ugliness displayed by Hannaford in particular, and this milieu more generally—moments which include a steady stream of lechery, racism, sexism, and homophobia (the later is particularly noxious in a scene in which Hannaford attacks a schoolmaster who has been brought out to confirm that his leading man is a trained actor who had faked drowning in order to meet the famous director, rather than the drifting beauty Hannaford assumed he had discovered in the process of saving his life)—is the point where the distance between the film’s production and its heavily delayed arrival threatens to obscure the film’s intelligence most forcefully. Are we to understand that Hannaford is a menace, a man capable of striking a woman, as he does Rich when she finally confronts him with her thesis, putting an end to the drive-in segment and effectively the film, because of his repressed sexuality? This, indeed, would seem just the sort of corny conclusion that “his admirers” reject in the opening voiceover monologue (there, they are speaking of the uncertainty as to whether Hannaford’s death is the result of suicide or drunk driving).

If The Other Side of the Wind strikes me as of more enduring interest than the ’70s films, with their “complicated” anti-heroes, it resembles in this regard, it is because there is no evidence that there is an authentic Hannaford being repressed. If this film is “against he-men” it is on the grounds that such men have made the wrong choice in their self-image vis-à-vis the social world they exist in, not vis-à-vis some inner truth a critic or anyone else is likely to extract—the Hannafords of the world perhaps themselves least of all. Several minutes later in the Maysles’ film, Welles responds to a question regarding his plans for casting by saying that he plans to fill the film with people “who are used to being images.” The idea, as underscored by Bogdanovich’s constant impersonations (Jimmy Stewart, Jerry Lewis, Cary Grant), which rhyme Welles’ tendency to overdub his actors’ voices with his own, is that an obsession with movies might repay whatever else it takes from an individual with an insight into the fundamental nature of what it is like to live within an image culture. If The Other Side of the Wind were made today, in our more enlightened times, we might assume that Hannaford, when John Dale arrives more than fashionably late at the party, would lead him into the bedroom and find some relief. It would, though, be only the belated satisfaction of a confidence man finding his mark. Welles, somewhere, behind a large glass of wine, would be having a laugh.

Phil Coldiron