El Gran Movimiento (Kiro Russo, Bolivia/France/Qatar/Switzerland)

By Jay Kuehner

The tacit assumption of the “city symphony” is of a metropolis invariably harmonious, conducive to and cooperative with the machinations of both camera and director, the coalescence of an industrial apparatus. Kiro Russo’s native La Paz defies any such arrangement in El Gran Movimiento, which channels the inherent dissonance and manifest disparity of the majestic yet disintegrating Bolivian city. Zooming vertiginously from the Altiplano to the sprawling city basin below, the camera alights with increasing detail on the teeming cityscape—the faded façades, clusters of wire, and peeling flyers—as if seeking some sentient trace amid the material thicket. Sound becomes amplified to a feverish pitch: honking cars, church bells, barking dogs, radio static, and, finally, street detonations. Characters, at last, are exhumed from anonymity, emerging from what thus far could be a lost ethnographic documentary reel: a trio of out-of-work miners who have marched seven days from the mines in Huanuni to join in a street protest to demand the reinstatement of their jobs. “Our feet hurt. Nights were cold,” confides a young man named Elder (Julio César Ticona) as his companion subjects him to a mock-interview on his camera phone—and, in a cheeky instance of the film’s reflexivity, calls him out as the lead in Russo’s 2016 film Viejo calavera (Dark Skull).

That Ticona is both this and also a real-life participant in the miners’ 2018 march from Huanuni is indicative of Russo’s productive ambivalence toward both fictive and documentary approaches. Rather than a cloying conceptual conceit, Russo’s particular spin on hybridity grants his nonprofessional actors the freedom to inhabit both real and imaginary realms, subject and character becoming synonymous. While this style may chime with current iterations of the international art film, in this case its roots can be located closer to home, in the work of Russo’s predecessor Jorge Sanjinés and the Ukamau Group—post-Blood of the Condor (1969) and consonant with Courage of the People (1971)—whose manifestos proposed a “Theory and Practice of a Cinema With the People” and envisioned the author as more of an instrument of its subjects’ lived experience and collective will. This tradition informs Russo’s otherwise recognizably neorealist tale of Elder and his fellow miners Gato (Gustavo Milán) and Gallo (Israel Hurtado) navigating their urban exile in search of sustaining day labour. The city’s labyrinthine Rodriguez Market, initially the site of a series of novel contrasts—country boys ogling hip sneakers and sweatshirts while cloaking themselves against the elements in dusty layers and monkish hoodies—gradually emerges as both the film’s primary stage and spiritual locus.

Elder, meanwhile, appears increasingly unwell: pale, coughing, and feverish, he struggles even just to loiter with his companions over swilled bottles of singani (although he is momentarily resurrected in a visit to a disco bar that has seemingly remained unchanged since the ’80s, where the miners are transformed under the pulse of the stroboscopic lamp and cheesy beats). The cause of his condition is at once obvious (his lungs are full of dust from the mines) and mysterious: perennially hunched, hobbling, or gliding ghostlike in the aerial trams above the city, Elder seems a figure beset by any number of less visible ills, from existential malaise to physical exhaustion and simple poverty (with pneumoconiosis and COVID implied). Could be the devil, reckons the elderly Mamá Pancha (Francisca Arce de Aro), claiming the ailing Elder as her godson while willing him back to health, into a job at the market, and away from bad company.

Elder’s physical decline occasions El Gran Movimiento’s metaphysical turn, as a potential supernatural cure increasingly comes to seem the only recourse for his ailment. This more fantastical dimension of the film is introduced via another elder: the reclusive shaman Max (Max Eduardo Bautista Uchasara), who resides in the forest beyond the city, gathering medicinal herbs and intoning on matters both empirical (the amount of cable in kilometres used to move the aerial tram) and mythic (the wretched beasts who come to graze in the long grass, or of shadows that turn into demons). While the vending cholitas at the market, propped in seeming perpetuity atop sacks of potatoes, tease him about his waning powers, the care with which Max attends to Mamá Pancha and, eventually, Elder, evinces a communal bond among this class of invisibles.

For her part, Mamá Pancha extends condolences even to the stingy boss at the market, who, having lost his mother some time ago, now appears intent on short-changing Elder and his companions, who he has employed to haul crates of produce, sacks of tubers, giant melons, and sundry furniture. The image of a sickened Elder, a shelf strapped to his back as he navigates the winding alleys of the market, suggests a local, anachronistic version of the Via Dolorosa. But Russo does not impose any excessive allegorical weight upon Elder, who appears to be crumbling to dust like the city itself: the Choqueyapu River, once brimming with gold, now flows with toxic mud; buildings lie in partially demolished conditions; pigeons coo in distress. While the film’s soundscape slyly translates a bit from the Alloy Orchestra’s score for Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), El Gran Movimiento begins to seem less a symphony of a city than an anatomy of one.

Even so, something like a soul seems to dwell beneath its ravaged face, as the incessant zooms and pans of DP Pablo Paniagua’s camera appear to be attempting to excavate the history embedded within the city’s walls. While the cholitas, who assume the role of chorus, tease Max for his overactive imagination, or what may simply be his capacious memory (“How many citizens live in your head?”), Russo conceives of him as a clown with empathic powers: a shaman whose kind is nearly extinct on account of modernization, his insight obscured but not obsolete. Literally holed up in a frond-covered slot at the brink of civilization, he stokes embers to write with and daubs himself with clay, as if preparing to take on the dynamic healing of poor Elder. (There may too be a bit of Apichatpong’s Boonmee in Max, recalling past lives as he does, though it’s not clear what to make of the white dog wandering his dreams and into the market stalls in the dead of night.) Whether clairvoyant or merely suffering from the same sulfurous haze as the miners, Max remains an enigma who transforms the film’s social-realist complexion into something more entrancingly oneiric; the smoke he’s blowing might just contain some of that oldest panacea, a little love.

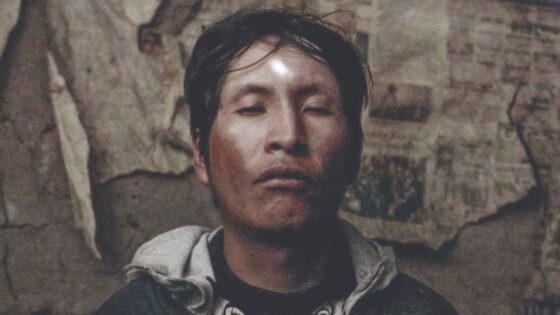

Deteriorating until he’s reduced to a virtual carcass, Elder is ultimately carried away from the market in the night like coal on a conveyor. Although Russo has kept his already impassive and inscrutable protagonist at a distance for much of the film’s duration, during the final bid to resurrect him the camera directly confronts his face: eyes rolled back, cheeks scarred, teeth glinting like miner’s lamps in the darkness of his own calavera. Without forgoing the political implications of his protagonist’s labour and suffering, Russo here intimates that there is something voluminous in what can’t be seen with even the most penetrating gaze. The film culminates in a montage not of buildings but of people, La Paz humanized by a succession of faces conjured from the multitude as Elder’s life appears to flash by before his (and our) eyes in an accelerated blitz of images. Ultimately, the great movement of the title is proved to be a cyclical one, breathing new life into a man left to expire too early.

Jay Kuehner