Film/Art | Camille Henrot: A Hunter-Gatherer During a Time of Collective “Grosse Fatigue”

By Andréa Picard

By Andréa Picard

“Ideas are a complete system within us, resembling a natural kingdom, a sort of flora, of which the iconography will one day be outlined by some man who will perhaps be accounted a madman.”—Honoré de Balzac, Louis Lambert, 1832

“How, in A.D. 1988, is it that human ingenuity has been unable, firstly via science in its many fields and secondly via believers with their various credos, to arrive at agreed definitive forms when, to general current perception the universe is a singular phenomenon…IS THERE A BLACK HOLE MEGATRUTH AT THE CENTER OF THE 20C TRAJECTORY…?”—John Latham & Ian Macdonald-Munro, 1988

Archive fever hasn’t really left us, yet it’s been increasingly tempered by a sense of exasperation: not enough money, not enough space, too much physical material, too much digital information, too much time required and energy spent. Which archives? Film archives for one, but also a wide-ranging span that includes natural history museums and other swelling repositories of species, specimens, collections, artworks, etc. For posterity’s sake, access is crucial and the collecting evermore ethical and philosophical, as is its interpretation. (One can easily speculate on the reasons why, aesthetic and otherwise, James Benning has been making a film at the formidable Natural History Museum in Vienna—bliss for vitrine fetishists—and Sokurov has been doing the same in the storied stock rooms of the Louvre.) This year’s Venice Biennale, curated by precocious multi-tasker Massimiliano Gioni, Artistic Director of the Nicola Trussardi Foundation as well as Associate Director and Director of Exhibitions at the New Museum, bore both a relevant and obvious title, “The Encyclopedic Palace.” Relevant because taxonomy has been radically redefined in our age and continues to stutter in paradoxical limbo. Its tools and mechanisms are in constant flux, updated incessantly, with the notion of the archive and the catalogue rendered instantaneous, pushed and pulled between the public and the personal. This is the personal as public phenomenon, the public made personal by design, and perhaps altogether less scientific or reliable than in the past, i.e., Wikipedia rather than encyclopedia: knowledge blurred by opinion. Of course, objectivity has eluded most fields of scientific study for reasons that are as obvious as they are insidious. Truth according to whom?

New York-based French artist Camille Henrot won the Silver Lion at Venice for best young promising artist for her “encyclopedic” video Grosse Fatigue, a huge popular and critical hit, and a work many considered the perfect encapsulation of the Biennale itself. A summation of curatorial impetus (refracted through the commission), but also of the history of the world in all of its colourful deviations, Grosse Fatigue is heady, steeped in creationist myths from a vast array of cultures, whose beginnings are nary the same. And nor are their deaths. A prolific, multidisciplinary artist, whose work ranges from sculpture and drawing to film and video, Henrot demonstrates a fervent fascination with the collection and circulation of objects, as well as symbols of the past and their estranged, present-day applications. (Her elegant, uncanny ikebana sculptures—titled Est-il possible d’être révolutionnaire et d’aimer les fleurs?—were one of the big hits of last year’s Paris Triennial, Intense Proximité, itself a bulimic display of knowledge and example of excess largely cast through a number of august anthropological and ethnographic explorations.)

Grosse Fatigue emerged from the artist’s fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution, where she dove into creationist myths spanning a wide range of religions, epochs, and geographic expanses, exhuming a multitude of artifacts and their legends. The video paradoxically partakes in the desire for totalizing cosmological knowledge and in the state of saturation, indeed exhaustion, that results from that subjective quest—one that, of course, extends to art-making itself and its critical analysis. An addictive mix of beats (yes beats!) and anthropology, Grosse Fatigue is video art as exhilarating nervous breakdown with an underlying plangent tone: a hymn or a lament, and/or an avowal of solitude in search of answers.

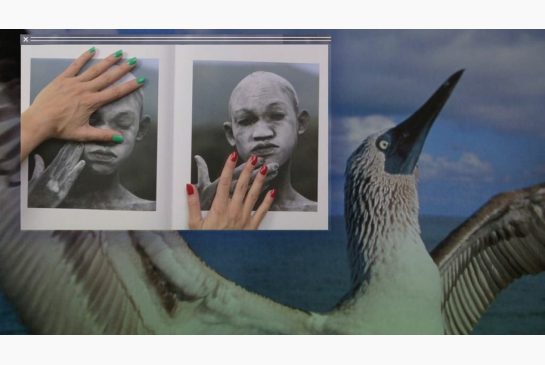

Like a literal embodiment of our anxious, knowledge-thirsty contemporary moment, the video is comprised of a succession of windows and folders opening and closing on a computer screen revealing a dizzying array of taxonomic information. Seventies slam poetry-style narration, written in collaboration with poet Jacob Bromberg and percussively scored by DJ Joakim Bouaziz (Henrot’s frequent collaborator) describes an increasingly breathless excursion through the history of the universe. “In the beginning there was…” and was, and was, suggesting an ad infinitum host of possibilities for the birth, life, and death of this complicated world we inhabit. Replete with cryptic quotes embedded in its bold spoken-word delivery (a fitting affront to minimalism considering its maximalist endeavour), Grosse Fatigue is an idiosyncratic mix of popular myth, anthropological findings, intellectual pilfering and citation, interface aesthetics, and a resolutely populist idiom. Its contradictions cohere around an ordering principle that deceptively defies its form. While each successive window suggests moving images that are “found” and reconstituted as if through a search engine, Grosse Fatigue is not a found-footage work in any conventional sense. In fact, it’s not a found-footage film at all. The footage is mostly original and shot by the artist herself, though—as attested to by the ubiquitous image of Toronto’s infamous shearling-coat-sporting Ikea Monkey—a few were sourced via the internet and appear on a computer monitor that comprises their alterable cosmos. But the windows upon windows of information, interspersed with more documentary-like footage of the conservation facilities at the Smithsonian, suggest a seemingly endless mise en abyme, which, especially given its context and subject matter, plays into a larger dialogue (equally evident and oblique) about the nature of artifacts, facsimiles, and worth (especially of objecthood in our age of de-materialization), inside and outside of the art and museum worlds.

Employing images of disjunctive mimicry as a clash of cultures, and hinting at the fickleness and surface polish of fashion and its anthropological implications (nail art and the zeitgeist), Grosse Fatigue demonstrates a conceptualist approach and palette that harnesses the aesthetics of the web (images that are perpetually minimized, maximized, overlapped, dragged), sometimes with footage that infers the cinema. Its multi-grid form of constantly moving images, we know, is routinely used to watch works of cinema as blocks of information removed from its material properties. If Grosse Fatigue ultimately signals an impossible search for harmonizing a totalizing knowledge, it does so through an avowal of solitude that, not unlike the communal act of watching a film projected in a cinema, seeks solace in a comforting, collective belief system and through the potential for thrilling discovery—one that both propels and placates a rapidly beating heart.

On the occasion of Grosse Fatigue’s inclusion in TIFF’s Future Projections program, Camille Henrot graciously took the time to answer some questions while in the midst of preparing her large solo exhibition, Cities of Ys, set to open at the New Orleans Museum of Art in early October.

Cinema Scope: The title, Grosse Fatigue, has already become iconic or emblematic of our contemporary mood. Did you have this title in mind at the outset of the project, or did it emerge as you conducted your research and presumably became overwhelmed with the inexhaustibility of it all?

Camille Henrot: Yes, it was a period in my life when everything felt very heavy and weighing. To take on the whole history of humanity is already a burden. The burden of the history of the universe is absurd by definition. When we think about the history of the universe we think about the beginning, the creative energy, but what’s important is what comes after…I wanted to insist on the un-glorious aspect of it in the title. Fatigue is mentioned in a lot of creation myths. It’s the loss of energy, the entropy principle, which is the founding principle of the creation of the universe.

Scope: Why tackle creationist myths today? What significance do they hold vis-à-vis our present-day moment?

Henrot: Today there is a lot of interest in the idea of the end of human civilization. This feeling probably emerges due to the virtual era and its “de-materialization.” But thinking about the end returns us to the beginning, the creation of a world. The novel by Jules Verne, The New Adam, tells the story of the disappearance of our civilization, and how the survivors become the new “first men.” As a personal point of view, it amuses me to think of creation myths in relation to the creation of an artist and take this as another version of a creation myth, with lightness. Origin and authenticity are often fetishized and used in ideology. So I wanted to approach this subject by criticizing this compulsion, without removing its beauty.

I think that the Smithsonian posits a rather interesting point of view because their approach is really open and thoughtful. I like the idea that in the Department of Anthropology at the Museum of Natural History, there is a “globalization” specialist, Joshua Bell, who wrote a text on braiding baskets called “beginnings and ends.” He is also present in the film, wearing blue gloves to show some Melanesian objects.

Scope: What were some of the most surprising, baffling, or spectacular discoveries made while at the Smithsonian?

Henrot: The Smithsonian database. While preparing for my stay in DC and researching the database, I was obsessively making screen captures of the strange combinations of images that were appearing on my computer when making “selections” of things I wanted to view. It was permanent chaos and cacophony, and I felt as if the history of the universe could be written with this spirit in mind.

Scope: While the video makes clever use of the internet form—its screensaver, windows, in short, its interface as a display-cum-montage of images—can you tell us about the actual images and footage? Did you largely shoot them? Deceptively, we are prone to imagine Grosse Fatigue as a found-footage work because of its structural framework (as a recycler or refresher of images), and yet it’s far more intricate than that.

Henrot: All of the moving images were shot specifically for the film. The only found images in the film are the wide-eyed white cats and the popular image of the Ikea Monkey who gets minimized into the shot of the rocket ship. I had prepared tons of folders with very crazy categories of found images from the web for the film, such as nail art, dead animals, decorated eggs, eye irritation, naked bodies, artists drawing in bed, writers writing while standing, water drops, anorexia, bicolour-eyed cats, and yet I only used maybe five percent of these images.

Scope: Has cinema’s role in how we see and experience the world changed as we’ve increasingly moved from a physical to a virtual taxonomy?

Henrot: During my research at the Smithsonian, I made lists of books that were interesting to me. One of them, Arénaire Archimedes, was interesting for a large number of reasons. It describes computers as being calculating machines. The computer supports the excessive size of the world (meaning the sheer quantity but also the diversity of views, practices, and the multiplication of individuals, along with the visual and textual traces they generate). The curator in charge of the medicine and science division at the National Museum of American History, Peggy Kidwell, gave me a text called “Joining the Network of Ideas, Impact of Digital Information on the General Workflow of Knowledge.” It was on hyper-media and how the computer window has been designed to leverage the possibilities of assimilation and connection. The concept of hyper-media seemed very interesting, and I haven’t found any other system of visual expression that can effectively express the issue of flow and disparity of information we face as humans with the internet.

It creates an order, but the multiplication of knowledge means that the order can only be personal and subjective. This makes sense because that subjective order can include any combination of ideas, whereas with a rational and objective system there will always be blind spots, which it cannot include because it would seem contradictory.

Scope: Can you discuss your choice of music for Grosse Fatigue? You’ve used bold music in the past—I’m thinking of your film Le Songe de Poliphile (2011) in particular—which is rhythmically propulsive but also partakes in a more subconscious reality, such as fear or erotic impulses.

Henrot: I’m very lucky to have collaborated with Joakim for a very long time, and he understands how to make the film become a very visceral experience through music.

I’m inspired by avant-garde cinema of the ’30s that refers to music and painting as models, not literature and theatre. I wrote my master’s thesis on slow motion, relating it to a Gutai painting and Asian action films, so I’ve always been very preoccupied by cinema as a “total art” and my very first films were music videos.

It was my aim for the film to reflect the anxiety generated by the open nature of the world and its excessive dimension. I decided to use hip hop because hip-hop beats have a universal planetary dimension that seems appropriate. It brings forth ideas of expense and excess (in the way George Bataille thinks of them).

I’m a big fan of hip hop music. I was in Cotonou in Benin last November, and the swimming pool at my hotel was used by a school class during the day. A kid was afraid to dive and another kid told him, to help him jump, “Do you think Wiz Khalifa would be afraid?” I then considered the origin of rap, spoken word poetry, the rhythm of language, and how we record voices. I was interested in a voice that could oscillate between conviction and vulnerability. The voice is that of Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh (part of the musical group Dragon of Zynth) who is also an actor. We had to work very hard with the recording since it was important to do it all in one take. Joakim designed music with the idea of minimal hip hop in mind, akin to the Pharrell Williams song “Drop It Like It’s Hot,” which is my favourite hip-hop song.

Scope: Is Grosse Fatigue your personal history of the universe pieced together from an accumulation of shared, even conflicting knowledge? How did you parse and privilege your research? And in this instance, what significance does the computer display have?

Henrot: Yes, that would be a good description. The question of focusing and eliminating was central to keeping my sanity. I knew that I would go crazy if I did not restrain the scope of the research, and yet I had the intuitive idea that only a sincere, all encompassing strategy would be an interesting project. This was something I then had to accept and give shape to.

Knowledge compulsion is also connected to narcissism and loneliness, that’s why I had this idea that the film should have a masturbation scene.

I was so overwhelmed by images and ideas of connections at night that I thought I was schizophrenic and started looking at the Wikipedia page about schizophrenia. That’s how these pages came to be included in the film.

I was relieved when I was able to integrate so much of the vulnerability of my own research (the crazy and messy parts of it) in a visual system that would be coherent with the subject. It was not very easy to explain my project to people and I really had to fight to get appointments or get access to things (especially the Natural History Museum, which was also the museum that was the most all-encompassing and therefore the most interesting to my research). It became very obvious that the “general” and “too broad” characteristic of my research was opposite to the scientific research process which focuses on a certain species within a certain genus, within a certain family, within a certain order and so on.

Scope: How can we even fathom harmonizing all human knowledge without losing our sanity?

Henrot: If you think about harmonizing all human knowledge you already have lost your sanity. But by sanity here, we of course mean rationality.

“The human mind has two irreconcilable fundamental aspirations. One is expressed by our language through a very significant image. It is understood as a synonym of the words ‘to know,’ ‘to grasp’ [saisire], and ‘to comprehend’ [comprendre]. We can only understand as a totality what we receive to hold in our hands.” History of Speculative thought (1896), Jonas Cohn (my translation).

Our desire to encompass all can only be experienced in a very humble proportion: our hands. That’s why hands are a repetitive pattern in my film. But enlarging the circle and putting more and more within it is a desire at the very origin of our human need. Writing an exhaustive history of the world is a violent way to take hold of it, to somehow “own” it. Preservation and conservation are paradoxically acts of destruction, and this classification anticipates the end of the world as we know it. This really resonates with Lévi-Strauss’ idea that at the root of anthropology is the end of mankind. The collection may allow certain species and certain cultures to survive, but is the notion of being saved by science actually precipitating our own destruction?

A harmonized universe…it’s a very scary thing to imagine. A world where everything has a meaning, and every gesture a cause. It’s a world with no possibility of poetry and conversation. No space between right and wrong. It would not be a nice place to live in because there would be no outside, no escape. But the truth is that we all have this ambivalent nostalgia of what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin calls the omega point, from one to many. There was a moment when everything that lived was fish, and we all have an intuitive memory of this.

Andrea Picard- « Previous

- 1

- 2