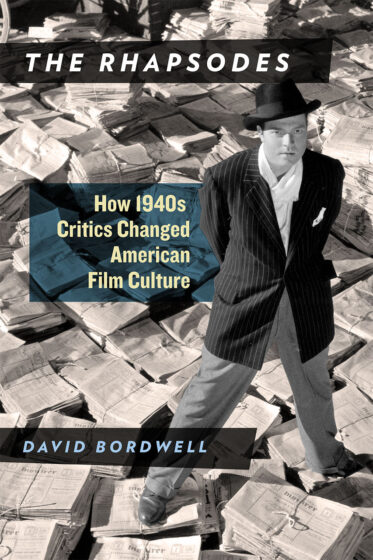

Before the Swarm: David Bordwell’s The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture

By Andrew Tracy

A friend recently pigeonholed me after he witnessed an onstage film critics panel and demanded I make amends for wasting his time—not because I had in any way obliged him to attend, but simply because I was guilty by association. “What’s the point of critics talking about criticism?” he demanded, which organically led him toward his next rhetorical query: “What the hell’s the point of writing criticism anyway?” Steering clear of that latter question (if only for reasons of self-preservation), I’ll cop to the first charge. Myself, I find it difficult to not talk about criticism when writing criticism—if only because these days there’s so damn much of it, and so much of it is so goddamn poor. “If you judge by sheer bulk, film criticism is flourishing as never before,” David Bordwell opens The Rhapsodes, keeping his tone cool even as he slyly evokes an insectoid image of “Critics swarm[ing] across our screens[:] writing for online magazines, chatting in podcasts and YouTube clips, tweeting their instant reactions.” Granted the fact that our digitized world has expanded the mediums and modes through which criticism can be practised, criticism is still an essentially literary medium in that it demands that one organize and present one’s thoughts—and as ever, thought remains in plenty short supply. In so much so-called criticism the operative belief seems to be that the saying of a thing is more important than how it is said; but having moved primarily to the other side of the editor’s desk (if such a thing even existed in the purely virtual Cinema Scope press room), I’ve discovered that inelegance of prose is often coterminous with incoherence, imprecision or, simply, absence of thought.

This is one of the critical undercurrents running through Bordwell’s study of the four ’40s critics whom, the subtitle contends, “changed American film culture”—though the avuncular scholar, with typical politeness, poses it as a postulate rather than a pronouncement. (“If a worthy critic must be an exceptional writer, my four critics meet the standard,” writes Bordwell; he does however show his hand when he declares that his quartet “remain far more provocative and penetrating than nearly anyone writing film criticism today.”) An expanded version of a series of entries that Bordwell originally wrote for his website (which themselves originated as part of a larger, forthcoming project on ’40s Hollywood cinema), The Rhapsodes offers swiftly sketched yet unfailingly incisive portraits of Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler, whom Bordwell contends created the “cult of personality” that led to the emergence of such celebrity critics as Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, and Roger Ebert in the ’60s and ’70s.

None of these writers has lacked for recognition previously—though only wacky word wrangler Farber, who passed away in 2008, lived long enough to enjoy anything other than the posthumous variety—but Bordwell’s comparative treatment of them here allows for a level of historical contextualization that tends to be scanted in other celebrations of their work; an exception is Greg Taylor’s excellent Artists in the Audience, a parallel study of Farber and Tyler approvingly cited by Bordwell in his endnotes. (Hastily, and with far less evidentiary basis, the present writer attempted to do something of the same in a long review of the Library of America’s Farber on Film collection in the Spring 2010 Cineaste.) Just as in his analyses of cinematic staging, editing, and storytelling techniques, in The Rhapsodes Bordwell traces both the direct and osmotic influences, the micro and macro frameworks that helped these four writers define their singular styles.

On the former point, there is a of course a clear bond between the first three of Bordwell’s subjects. Farber succeeded Ferguson as film critic at The New Republic after the latter went off to war and died at sea, and combined Ferguson’s slangy, jazzy, wiseacre style with a formalist sensitivity derived from his work as a painter and art critic; Agee and Farber were friends, with Agee occasionally making approving mention of Farber in his reviews, something not reciprocated by Farber until a (not entirely laudatory) obit after Agee’s death in 1955. Tyler is the odd man out of the four, a dweller on the homosexual dandy wing of their shared bohemian NYC milieu, his style cheekily heightened and consciously (pre-)camp as opposed to the all-American idiomatic mix-and-matching of the Otis-Jim-Manny troika.

As does Taylor in Artists in the Audience, Bordwell situates his writers against the background of the mid-century high/middle/lowbrow mass-culture debate, where their wholehearted engagement with movies stood in stark contrast to the prevailing cultural gatekeepers’ dismissive or dilettantish treatment of the world’s then most pervasive and popular art. But whereas Taylor depicts Farber and Tyler’s respective careers as a constant jockeying for cultural position—seeking to establish and maintain the critic’s supremacy over film, audience, and their fellow commentators alike—Bordwell takes a more ingenuous view of his rhapsodes. Although writing in a cultural atmosphere then influenced by the puritanical high modernism preached by Clement Greenberg and the kind of left-elitist disdain for mass art later embodied in the Horkheimer-Adorno Culture Industry thesis, Ferguson, Farber, Agee and Tyler, claims Bordwell, “outflanked the mass culture debates by simply diving, quite self-consciously, into popular material…making distinctions and discriminations of fine degree [and finding] God, or the devil, in the details.” “Practical aesthetes” Bordwell brands them, seeking out stray moments of beauty, expressiveness, or startling insight in supposedly machine-tooled product.

What interests Bordwell in these critics, however, is not only the cultural-ideological shift they represented, and helped effect, in attitudes toward and commentary on American mass culture. As part and parcel of that, he is interested in these writers as writers—in the techniques, tone, and textures of their writing, which are inseparable from their thinking about their chosen subject. If “all four function as performers” in language, “spread[ing] out American idioms like a magician fanning a fistful of cards,” Bordwell shows that, like all illusionists, they planned their tricks carefully in advance. While his book’s very title brands his foursome as proselytizers whose transporting enthusiasm carries them away, Bordwell demonstrates, through patient parsing of their prose, how each of these writers, in considering an innately and effortlessly heterogeneous medium, cultivated a prismatic perspective to convey its unique beauties in words.

Unsurprisingly for an unabashed shot-timer and frame-grabber, Bordwell posits the descriptive aspect of these critics’ work as one of their essential traits. Though contrarian posturing surely played some role in their enthusiasms and condemnations, in Bordwell’s telling these writers were attempting to bring to film criticism the kind of serious, attentive, and analytical readings then current in literary studies and musicology. Considering Ferguson’s on-set reports on the shooting of two scenes for Out of the Fog and The Little Foxes (both 1941), Bordwell remarks that “for possibly the first time in American film criticism, a reviewer describes a scene shot by shot in relation to production practices”; later, he links Agee’s epic three-part review of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947) to the pervasiveness of close-reading literary criticism in the late ’40s, and Agee’s own early studies under New Criticism dean I.A. Richards. Exercising his astute pictorial sensibility, Farber—whom during this period, as Bordwell demonstrates, was far less inclined to introduce art-world references in his film criticism—locates and defines the “expressive naturalism” of Hollywood staging strategies. Even Tyler’s Hollywood hallucinations, his wildly sensuous flights into the mythopoetic firmament and psychoanalytic substrata of seemingly routine weekly releases, work to identify the innate catholicity of Hollywood storytelling—a seamless impurity of form that Bordwell (in, obviously, a very different mode and manner) has posited in his own work as the “utterly opportunistic and promiscuous” nature of film narrative, “seiz[ing] anything that can serve its purpose [and] slap[ping] together all manner of disparate cues.”

However, Bordwell—no mean prose stylist himself—does not simply recruit his rhapsodes for the knowledge-producing, craft-centric model of academic film study to which he subscribes. Painting Agee as a modern-day Romantic, Bordwell finds in the fretful, incessant doubling-back of his documentary sharecropper opus Let Us Now Praise Famous Men the search for “a galaxy of facts beyond comprehension”; “The creative task,” Bordwell paraphrases Agee “is to transcend realism, to retain respect for the way things are while showing the fire at the core of the world.” Even as they ferreted out evidence of artistic intention from within that famously “invisible” Hollywood style, each of these critics was using the film before them as fodder for their own striving imaginations.

It’s thus that all four rhapsodes variously reject Citizen Kane (1941), the undeclared secret sharer of Bordwell’s book (though his publishers signal it some by plastering it on the cover). In Welles’ wunderkindery these critics discerned an almost tyrannical enclosure of the film image, a shutting out of any reality beyond the overly designed frame—and, with it, the imaginative work of the critic. Tyler’s flights of fancy, or aspiring screenwriter Agee’s penchant for rewriting/redirecting in his reviews those films he found frustratingly wanting, are only the most obvious manifestations of a shared impulse among these men. Each, in his own particular way, was inspired, enthralled, or haunted by the vision of something beyond what he was seeing with his eyes. Implicitly (and then explicitly) rejecting the restrictively materialist modernism of Greenberg, Farber “anticipat[ed] Bazin’s conception of the porous frame” by celebrating filmmakers’ subtle evocation of a boundless world extending beyond the limits of the film image. Even the hard-boiled pragmatist Ferguson, who celebrated the many-handed, artisanal nature of Hollywood production (akin to his favouring of the big-band model of jazz), saw the ultimate ideal, in a film’s precise orchestration of its various parts, as being the creation of the ineffable aura of real life as it is lived—a goal as mystical in its way as any of Agee’s fervent striving after transcendence.

Wellesian without portfolio though he be, Bordwell remains even-handed in his discussion of his subjects’ assorted Kane condemnations—though his abiding interest in Welles’ debut as an historical nexus of stylistic and narrative strategies may feed in somewhat to his concluding comments about the restrictions of the rhapsodes’ field of view. “These writers activate so many aspects of the classics [that] I’m surprised they didn’t flag other things that [now] pop out for us,” he writes. “They mostly missed the stylistic revolution of deep focus, the long take, and extensive camera movement…Tyler is sublimely indifferent to directors altogether (except Welles and avant-gardists), while Agee and Farber largely neglect Preminger, Mann, Siodmak, Sirk, Fuller, and Ophüls.”

Farber, of course, made up for some of those oversights in his “classic” period in the ’50s and ’60s, when he inaugurated his now famous championing of tough crime pictures and hard-hitting melodramas—a then-countercanon that, in its attitude and philosophy if not always its specific films, bears a striking resemblance to the classical Hollywood pantheon of contemporary cinephilia. But the decade of work that Bordwell focuses on is not simply a vanished prehistory, an early and imperfect evolutionary stage. Rather, the considerable distance of these writers from today’s tastes makes their work an alternative (or corrective) to some of the engrained habits and prejudices of current criticism.

For his part, Bordwell sees his rhapsodes as presenting a more “balanced picture of Hollywood then and now,” their openness to the softer virtues of “poignancy and romantic passion” a welcome tonic to today’s fondness for toughness, cynicism, and “swaggering aggression” in one’s filmmakers. While I don’t think that an appreciation of the lyrical is totally absent from contemporary cinephilic culture—look at all the mooning over Malick in certain corners, par exemple—it’s undoubtedly true that more (primarily digital) ink is spilled sussing out the so-called intricacies of blunt-force films than speaking to the gentler angels of our cinematic nature. (Lord knows that, his own chorus of rhapsodes aside, Malick is more often mocked, and with a viciousness and contempt that would never be applied to a Nicolas Winding Refn, say.)

Beyond matters of taste, however, is the fact that what these writers strove mightily to do—provide nuanced interpretation of the films before them based on the visual evidence on screen—is now technically (and technologically) feasible for contemporary critics as it never could have been in the rhapsodes’ time. All too often, however, writers today are content to forego analysis for unfounded assertion, vapid description, zeitgeist surfing, or contrarian posturing—the latter the bratty offspring of the actual cultural challenge once posed by Agee, Farber et al., a re-enactment of old battles that refuses to acknowledge that the cultural ground has shifted more than a little in the past, oh, two-thirds of a century.

That shifting ground has certainly resulted in some benefits to criticism, in terms of the range of people and perspectives whose entry to the field have widened and enriched our frames of reference. But as ever, widening has as its corollary a thinning out, and a plurality of voices the potential to become a cacophony. Not to mention the fact that, in their often tenuous grasp on how to use the language they are ostensibly writing in, many of those purporting to practise criticism remain blithely unaware of the fact that words can not only be containers for ideas, but creators of them. The unique prose styles of Bordwell’s quartet, in their doublings-back, their layers of paradox, their freewheeling associations and sudden conceptual leaps, personify film criticism as the drama of thought—a wrestling with both the visible and invisible evidence of the film before them, set against the implicit vision of the Total Film they dream of. If much criticism these days does indeed give evidence of struggle, it’s most often only against the laws of language and the limits of ignorance—and it’s a struggle bereft of drama, dreams, and most definitely thought.

Andrew Tracy