Global Discoveries on DVD | Yes and/or No

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

It’s customary for this column to focus on items that I know are currently available. But sometimes there are important potential or upcoming releases whose release dates remain uncertain when my column is written, and there are two of them I want to signal for this quarter, both of which I already possess copies of although they still weren’t commercially available when I wrote most of the following.

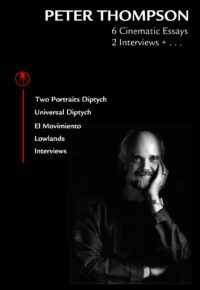

The first of these, the four-disc Peter Thompson: 6 Cinematic Essays + 2 Interviews + …, is to my mind the most important DVD release of the year—and this even in a year that has seen the final, long-delayed, and triumphant releases of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and the films of Pere Portabella (both discussed in previous columns)—because it represents the most flagrant discrepancy I know between work that is staggeringly powerful and important on the one hand and almost completely unknown on the other. For me, the late Peter Thompson (1944-2013) is the greatest of all Chicago filmmakers, living or dead, but it seems that the only reason why you haven’t heard of him is that he didn’t know how to hustle. Around October 31, the box set finally became available on Amazon; in the case of Far from Afghanistan (2012)—a collective film by John Gianvito, Jon Jost, Soon-Mi Yoo, Minda Martin, Travis Wilkerson, and Afghan Voices, overseen by Gianvito—there’s a URL listed on the DVD (farfromafghanistan.com), but it couldn’t be accessed the last time I checked. However, Gianvito has informed me that “inquiries about purchasing DVDs can be sent to farfromafghanistan@gmail.com, $15 per disc plus shipping.” (For writing that I’ve already published about the films on these releases, go to jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/10/a-handful-of-world-the-films-of-peter-thompson-an-introduction-and-interview/ and jonathanrosenbaum.net/2012/11/at-the-viennale-chris-marker-lives-tk/.)

The first of these, the four-disc Peter Thompson: 6 Cinematic Essays + 2 Interviews + …, is to my mind the most important DVD release of the year—and this even in a year that has seen the final, long-delayed, and triumphant releases of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and the films of Pere Portabella (both discussed in previous columns)—because it represents the most flagrant discrepancy I know between work that is staggeringly powerful and important on the one hand and almost completely unknown on the other. For me, the late Peter Thompson (1944-2013) is the greatest of all Chicago filmmakers, living or dead, but it seems that the only reason why you haven’t heard of him is that he didn’t know how to hustle. Around October 31, the box set finally became available on Amazon; in the case of Far from Afghanistan (2012)—a collective film by John Gianvito, Jon Jost, Soon-Mi Yoo, Minda Martin, Travis Wilkerson, and Afghan Voices, overseen by Gianvito—there’s a URL listed on the DVD (farfromafghanistan.com), but it couldn’t be accessed the last time I checked. However, Gianvito has informed me that “inquiries about purchasing DVDs can be sent to farfromafghanistan@gmail.com, $15 per disc plus shipping.” (For writing that I’ve already published about the films on these releases, go to jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/10/a-handful-of-world-the-films-of-peter-thompson-an-introduction-and-interview/ and jonathanrosenbaum.net/2012/11/at-the-viennale-chris-marker-lives-tk/.)

Are there conflict-of-interest issues here? Not really, or at least not exactly: Thompson was a dear friend, and so is Gianvito, but in both cases these friendships developed because of my enthusiasm for their work. For the record, I helped to conduct both of the “2 interviews” on the Thompson set (proceeds of which will go towards a scholarship named after Peter at Chicago’s Columbia College, where he taught photography for many years), but I had no such involvement in the slim single-disc Gianvito package.

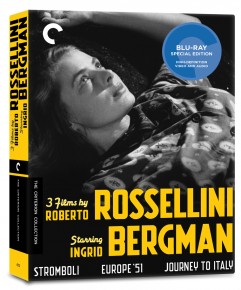

3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman (Criterion Blu-ray). This splendid box set, containing Stromboli (1950), Europa ’51 (1952), and Journey to Italy (1952), and crammed with valuable extras and an 86-page booklet, also gives us the separate Italian- and English-language versions of both Stromboli and Europa ’51. I should confess that Europa ’51, the least well-known of these three films, remains the one I’ve always preferred and found the most moving, and the original Italian version (nine minutes longer) is something of a revelation, for reasons that are explained in lucid and copious detail in one of the extras by film historian Elena Dagrada. (I haven’t yet looked at either of the versions of Stromboli, but it’s worth noting that in this case the English version is six minutes longer.) This is a package that I’m only starting to become acquainted with, but it’s obvious that there’s enough here to keep one busy for weeks.

3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman (Criterion Blu-ray). This splendid box set, containing Stromboli (1950), Europa ’51 (1952), and Journey to Italy (1952), and crammed with valuable extras and an 86-page booklet, also gives us the separate Italian- and English-language versions of both Stromboli and Europa ’51. I should confess that Europa ’51, the least well-known of these three films, remains the one I’ve always preferred and found the most moving, and the original Italian version (nine minutes longer) is something of a revelation, for reasons that are explained in lucid and copious detail in one of the extras by film historian Elena Dagrada. (I haven’t yet looked at either of the versions of Stromboli, but it’s worth noting that in this case the English version is six minutes longer.) This is a package that I’m only starting to become acquainted with, but it’s obvious that there’s enough here to keep one busy for weeks.

Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation (Kino Lorber). Having lived in Greenwich Village for much of the ’60s, I was driven by nostalgia to watch Laura Archibald’s documentary about the folk-music scene there, but was largely unsatisfied by many of the musical as well as geographical choices, which often made me feel that the generation being defined wasn’t mine (apart from an agreeable emphasis on Pete Seeger). Unless I missed something, Joan Baez, the New Lost City Ramblers, and even the Kingston Trio all go unmentioned, although one does get to see a neat performance by Joan’s sister and brother-in-law, Mimi and Richard Fariña, of a catchy protest song about the HUAC that isn’t mentioned in David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street. I also regretted the total absence of my own Village hangouts in the early ’60s—not just jazz clubs such as Jazz Gallery, the Five Spot, the Half Note and the Vanguard (understandable omissions), but also the Café Figaro, the Hip Bagel just behind it (where you could actually order a Bessie Smith Sundae), and the Fat Black Pussycat, all within the same couple of blocks as the apparent hotspots this film keeps returning to, even when it has to repeat the same archival clips. Perhaps the musical selections were limited by costs and clearances, and the sense of the neighbourhood (which excludes the East Village entirely) limited by the filmmakers’ generational distance.

Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation (Kino Lorber). Having lived in Greenwich Village for much of the ’60s, I was driven by nostalgia to watch Laura Archibald’s documentary about the folk-music scene there, but was largely unsatisfied by many of the musical as well as geographical choices, which often made me feel that the generation being defined wasn’t mine (apart from an agreeable emphasis on Pete Seeger). Unless I missed something, Joan Baez, the New Lost City Ramblers, and even the Kingston Trio all go unmentioned, although one does get to see a neat performance by Joan’s sister and brother-in-law, Mimi and Richard Fariña, of a catchy protest song about the HUAC that isn’t mentioned in David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street. I also regretted the total absence of my own Village hangouts in the early ’60s—not just jazz clubs such as Jazz Gallery, the Five Spot, the Half Note and the Vanguard (understandable omissions), but also the Café Figaro, the Hip Bagel just behind it (where you could actually order a Bessie Smith Sundae), and the Fat Black Pussycat, all within the same couple of blocks as the apparent hotspots this film keeps returning to, even when it has to repeat the same archival clips. Perhaps the musical selections were limited by costs and clearances, and the sense of the neighbourhood (which excludes the East Village entirely) limited by the filmmakers’ generational distance.

Riddles of the Sphinx (BFI Dual-format Edition). For better and for worse, there are few British films that make me feel more like an American yahoo than the second theoretical-experimental feature of Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen (1977), at once brilliant and intractable. Their first was the American-made Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazon (1974), shot in Evanston, Illinois, which I reviewed quite supportively for Monthly Film Bulletin, but I’ve never been able to shake off a certain ambivalence about it ever since. The same ambivalence that led some local cinephiles at the time to ironically tag Mulvey and Wollen as “the Royal Family,” voicing public support while occasionally expressing private demurrals about such particulars as Mulvey’s upper-class accent, also led me to feel some reluctance about rewatching Riddles over three decades later strictly on its own terms, without the benefit of Mulvey’s audio commentary. (Penthesilea, I should add, is included on this release as an extra, along with a video interview with Mulvey about it. I should also note, belatedly, that the only audio commentary provided on the Criterion Rossellini set is in fact Mulvey’s, on Journey to Italy.) The high value placed on the badges associated with conformity and correctness rather than originality or poetry in this sort of endeavour will always limit its appeal for me.

Riddles of the Sphinx (BFI Dual-format Edition). For better and for worse, there are few British films that make me feel more like an American yahoo than the second theoretical-experimental feature of Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen (1977), at once brilliant and intractable. Their first was the American-made Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazon (1974), shot in Evanston, Illinois, which I reviewed quite supportively for Monthly Film Bulletin, but I’ve never been able to shake off a certain ambivalence about it ever since. The same ambivalence that led some local cinephiles at the time to ironically tag Mulvey and Wollen as “the Royal Family,” voicing public support while occasionally expressing private demurrals about such particulars as Mulvey’s upper-class accent, also led me to feel some reluctance about rewatching Riddles over three decades later strictly on its own terms, without the benefit of Mulvey’s audio commentary. (Penthesilea, I should add, is included on this release as an extra, along with a video interview with Mulvey about it. I should also note, belatedly, that the only audio commentary provided on the Criterion Rossellini set is in fact Mulvey’s, on Journey to Italy.) The high value placed on the badges associated with conformity and correctness rather than originality or poetry in this sort of endeavour will always limit its appeal for me.

Beginning with a Table of Contents listing its seven sections that actually suggests a DVD menu avant la lettre, Riddles of the Sphinx, like its predecessor, functions at times more as an embodiment and extension of 1970s Screen theory than as an application of it, raising again the question of what one is supposed to do with all this apparatus except for nod (or shake) one’s head at its politics and programmatic approach to theory, especially if one isn’t an academic or a Lacanian. Mulvey’s commentary proves in some ways to be as interesting as the film itself, but this only confirms the degree to which my own role as spectator seems almost superfluous to all those circular 360-degree pans and intricate colour-coding; even without the audio commentary, the film comes equipped with its own built-in reading strategies, making creative participation limited. But it remains an important and significant historical marker regardless of whether one enjoys it or not, which I suppose has always been part of its point. (One quibble about Mulvey’s memory: in response to a question from interviewer Winfried Pauleit about whether Jeanne Dielman might have exerted some influence on Riddles—in fact, I don’t believe it did—Mulvey maintains that it couldn’t have because the two films were being made at the same time. But I recall seeing Mulvey at Jeanne Dielman’s first London screening in late 1975, a good year before Ken Jacobs’ Tom Tom the Piper’s Son turned up in the UK, which she acknowledges elsewhere on this audio commentary was a conscious influence.)

The Stranger (Kino Classics DVD). Mastered in HD from a 35mm print at the Library of Congress, this is the best version of Orson Welles’ 1946 thriller that we’re likely to get in the foreseeable future, after an endless stream of poor public domain copies. The choice of extras is excellent: Death Mills, the English-language version of a postwar (1945) 21-minute documentary produced by Billy Wilder for the purpose of showing German people the atrocities perpetrated in their name (a few glimpses of this film are provided in The Stranger, but I should add that at its full length, it is the most horrifying and grim of all the filmic accounts of this kind that I can recall seeing); three of Welles’ wartime radio broadcasts from 1942, and his 1946 commentary about the Bikini atomic bomb test; and an audio commentary to the feature by Bret Wood, producer of this release and author of the 1991 Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography.

The Stranger (Kino Classics DVD). Mastered in HD from a 35mm print at the Library of Congress, this is the best version of Orson Welles’ 1946 thriller that we’re likely to get in the foreseeable future, after an endless stream of poor public domain copies. The choice of extras is excellent: Death Mills, the English-language version of a postwar (1945) 21-minute documentary produced by Billy Wilder for the purpose of showing German people the atrocities perpetrated in their name (a few glimpses of this film are provided in The Stranger, but I should add that at its full length, it is the most horrifying and grim of all the filmic accounts of this kind that I can recall seeing); three of Welles’ wartime radio broadcasts from 1942, and his 1946 commentary about the Bikini atomic bomb test; and an audio commentary to the feature by Bret Wood, producer of this release and author of the 1991 Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography.

As in his book, Wood is more persuasive to me as a film historian than he is as a critic, but I should add that The Stranger is the only one of Welles’ 13 released features that I actively dislike. It’s also the only one that turned a profit during its first release: by his own testimony, Welles directed it in order to prove that he could deliver a commercial assignment just like anyone else—without cynicism but without much personal investment either—although it’s doubtful whether it did anything to bolster his career, in Hollywood or anywhere else. (If any proof were needed that Welles couldn’t please the industry even when he did everything he was supposed to, this is surely it.) I find Bronislaw Kaper’s hokey score atrocious, and can accept almost none of the film’s characters as interesting or believable, apart from Billy House’s pharmacist, whom Welles apparently invented because he was as bored with the plot he was handed as I was. (Welles’ own bombastic performance as the head villain strikes me as especially bad.) James Naremore’s pithy critical summary in The Magic World of Orson Welles seems pretty much on the mark to me, although he ranks Loretta Young’s performance somewhat higher than I do. (Maybe if her character didn’t come across so much like a bimbo, I would have admired her more.) Naremore’s account of the pre-release version of The Stranger, which was half an hour longer, suggests it must have been far more interesting, though it’s impossible to guess whether it would have functioned any better, either commercially or artistically. As it stands, it seems more like a pretentious effort to imitate Welles’ worst qualities as a director than as something he cooked up himself.

Ikarie XB 1 (Second Run DVD). A fascinating, well-crafted and unusually intelligent black-and-white ’Scope SF outer-space spectacular from Czechoslovakia in 1963, outfitted with informative extras—a new essay by Michael Brooke and a filmed interview with Kim Newman—about the film’s checkered history in the West (when American International Pictures released a mangled and dubbed version known as Voyage to the End of the Universe) as well as its more respectful handling in the East. Adapted from an early Stanislaw Lem novel, it seems to have exerted a stronger influence on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969) and Solaris (1972) than Kubrick and Tarkovsky seemed prepared to admit, and it testifies to the greater artistic prestige science fiction had in the Soviet bloc during this period.

Ikarie XB 1 (Second Run DVD). A fascinating, well-crafted and unusually intelligent black-and-white ’Scope SF outer-space spectacular from Czechoslovakia in 1963, outfitted with informative extras—a new essay by Michael Brooke and a filmed interview with Kim Newman—about the film’s checkered history in the West (when American International Pictures released a mangled and dubbed version known as Voyage to the End of the Universe) as well as its more respectful handling in the East. Adapted from an early Stanislaw Lem novel, it seems to have exerted a stronger influence on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969) and Solaris (1972) than Kubrick and Tarkovsky seemed prepared to admit, and it testifies to the greater artistic prestige science fiction had in the Soviet bloc during this period.

Two excellent Criterion Blu-rays of fantasy classics, René Clair’s I Married a Witch (1942) and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960). But I have more than a little bit of a bone to pick with one passage in David Kalat’s essay, in the booklet appended to the latter: “Franju operated the Cinémathèque as a glorified film club—at heart, he was a fan. Whereas some of his contemporaries such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Claude Chabrol were film critics who picked up cameras to put their theories into practice, Franju was ever apart from the New Wave. He was just a film buff—steeped in a passion for pulp.” But has Kalat, with his own passion for pulp, ever read Franju’s 1937 essay “Le Style de Fritz Lang,” an abridged English translation of which appears on the final page of the June 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin? If he hasn’t, he should: surely this is the work of a serious critic, not just a mere fan. The same might be said of Franju’s 1963 Judex, released the same year as Godard’s Les carabiniers and Le mépris, and no less a critical commentary; and for that matter, the interview with Franju included on this disc is by no means free of theoretical reflections about his practice. Incidentally, it’s great to have Franju’s extraordinary 1949 short Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes) on the same disc, but I lament the continuing absence on DVD and Blu-ray of his almost equally fine and no less corrosive Hôtel des Invalides (1952), which still awaits rediscovery, at least on this side of the Atlantic.

Two excellent Criterion Blu-rays of fantasy classics, René Clair’s I Married a Witch (1942) and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960). But I have more than a little bit of a bone to pick with one passage in David Kalat’s essay, in the booklet appended to the latter: “Franju operated the Cinémathèque as a glorified film club—at heart, he was a fan. Whereas some of his contemporaries such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Claude Chabrol were film critics who picked up cameras to put their theories into practice, Franju was ever apart from the New Wave. He was just a film buff—steeped in a passion for pulp.” But has Kalat, with his own passion for pulp, ever read Franju’s 1937 essay “Le Style de Fritz Lang,” an abridged English translation of which appears on the final page of the June 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin? If he hasn’t, he should: surely this is the work of a serious critic, not just a mere fan. The same might be said of Franju’s 1963 Judex, released the same year as Godard’s Les carabiniers and Le mépris, and no less a critical commentary; and for that matter, the interview with Franju included on this disc is by no means free of theoretical reflections about his practice. Incidentally, it’s great to have Franju’s extraordinary 1949 short Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes) on the same disc, but I lament the continuing absence on DVD and Blu-ray of his almost equally fine and no less corrosive Hôtel des Invalides (1952), which still awaits rediscovery, at least on this side of the Atlantic.

From a memoir written in the early ’80s, “Putting Back the Ritz,” about seeing I Married a Witch on a double bill with the original black-and-white Li’l Abner at the age of six, on Labor Day 1949, with two of my brothers and a black babysitter up in the “colored section” of the Ritz Theater in Sheffield, Alabama:

From a memoir written in the early ’80s, “Putting Back the Ritz,” about seeing I Married a Witch on a double bill with the original black-and-white Li’l Abner at the age of six, on Labor Day 1949, with two of my brothers and a black babysitter up in the “colored section” of the Ritz Theater in Sheffield, Alabama:

The principal moment I’m left with is a shot of two smoky essences in bottles, the sound of dry autumn leaves rustling through a chill night wind, and the voices of Cecil Kellaway and Veronica Lake, father and daughter, conversing from their adjacent bottles. Most of this has to do with Veronica Lake’s deep, husky voice: a smoky spirit whose name and form collectively conjured up a feminine aura of water, vapor, air, smoke, and flesh at the same time—a floating dreamboat that any boy of six would be proud to be married to. Having just seen Topper at the Princess the week before, I had all I needed to complete my erotic evaporation fantasies and crawl into the diaphanous lap of Lady Veronica. Indeed, by the time the credits of René Clair’s supernatural comedy came on, the ads had already done their work, and I was already invisibly inside her bottle too, ready to share in her throaty vibrato.

In the audio interview with Clair included with this release, he plausibly confesses to interviewer Gideon Bachmann that he isn’t at all sure he knows what “avant-garde” is or means in relation to cinema. He has a point, but even so, the shots of two bottles accompanied by Lake and Kellaway’s off-screen voices puts me in mind of the late Raúl Ruiz’s never-realized dream project of making a film out of Hamlet with a cast of vegetables.

During my very first trip to Russia, as a juror at the Message to Man International Film Festival in St. Petersburg, two of my fellow jurors, Niko von Glasow and Mira Nair (head of the jury), kindly gave me films of theirs as parting gifts, both of which I saw as soon as I returned home and thoroughly enjoyed, and both of which are commercially available: Nair’s fiction feature Hysterical Blindness (2002, available from HBO Studios for only $6.43 USD), and von Glasow’s documentary Nobody’s Perfect (2008, available from the aptly named Alive Mind for $12.26 USD).

During my very first trip to Russia, as a juror at the Message to Man International Film Festival in St. Petersburg, two of my fellow jurors, Niko von Glasow and Mira Nair (head of the jury), kindly gave me films of theirs as parting gifts, both of which I saw as soon as I returned home and thoroughly enjoyed, and both of which are commercially available: Nair’s fiction feature Hysterical Blindness (2002, available from HBO Studios for only $6.43 USD), and von Glasow’s documentary Nobody’s Perfect (2008, available from the aptly named Alive Mind for $12.26 USD).

Mira described her film to me as a sort of homage to Cassavetes, partly because Gena Rowlands and Ben Gazzara, both of them terrific here, are two of the stars (along with Uma Thurman, who plays Rowlands’ daughter, and Juliette Lewis). In a way, the movie can be read as a sort of feminist tweak on the sorrowful theme of male cruising as it’s charted in Shadows (1959), Faces (1968), and Husbands (1970), Cassavetes’ first three independent features, amply showing how female cruising can be no less desperate. By contrast, good humour and resourcefulness might be seen as the outstanding qualities of Nobody’s Perfect. Born disabled due to the side effects of the drug thalidomide, von Glasow sets out to film a nude calendar featuring himself and 11 others, male and female, afflicted by the same condition, all of whom he tracks down, gets to know, and gets us to know. The results prove to be funny and enabling as well as ennobling, even if some portions of the closing stretches call to mind Michael Moore’s Roger & Me (1989) and Bowling for Columbine (2002).

Mira described her film to me as a sort of homage to Cassavetes, partly because Gena Rowlands and Ben Gazzara, both of them terrific here, are two of the stars (along with Uma Thurman, who plays Rowlands’ daughter, and Juliette Lewis). In a way, the movie can be read as a sort of feminist tweak on the sorrowful theme of male cruising as it’s charted in Shadows (1959), Faces (1968), and Husbands (1970), Cassavetes’ first three independent features, amply showing how female cruising can be no less desperate. By contrast, good humour and resourcefulness might be seen as the outstanding qualities of Nobody’s Perfect. Born disabled due to the side effects of the drug thalidomide, von Glasow sets out to film a nude calendar featuring himself and 11 others, male and female, afflicted by the same condition, all of whom he tracks down, gets to know, and gets us to know. The results prove to be funny and enabling as well as ennobling, even if some portions of the closing stretches call to mind Michael Moore’s Roger & Me (1989) and Bowling for Columbine (2002).

The Unspeakable Act (Cinema Guild DVD). Trying to account for the beauty, power, and tenderness of this fine 2012 American independent feature by Dan Sallitt—about the potentially incestuous bond between a brother and sister, and the sister’s traumatic difficulties in sorting out and working through her own feelings about it—I’m immediately reminded of the beauty, power, and tenderness of my favourite single sentence in Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema, from the entry on Nicholas Ray: “Fortunately, Ray does have a theme, and a very important one; namely, that every relationship establishes its own moral code and that there is no such thing as abstract morality.”

The Unspeakable Act (Cinema Guild DVD). Trying to account for the beauty, power, and tenderness of this fine 2012 American independent feature by Dan Sallitt—about the potentially incestuous bond between a brother and sister, and the sister’s traumatic difficulties in sorting out and working through her own feelings about it—I’m immediately reminded of the beauty, power, and tenderness of my favourite single sentence in Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema, from the entry on Nicholas Ray: “Fortunately, Ray does have a theme, and a very important one; namely, that every relationship establishes its own moral code and that there is no such thing as abstract morality.”

Mysterious Island. I’m talking about the 15-chapter serial of 1951, directed by Spencer Bennet (and available for a mere $7.99 from cheezyflicks.com, less than half of what Amazon charges), not the Cy Endfield/Ray Harryhausen blunderbuss of a decade later. Even though part of my enthusiasm is nostalgia for the unadulterated pleasure this low-budgeter gave me when I was eight years old, I would still maintain that the delicacy and tenderness of this Victorian, Verne-derived adventure are worth a lot more to adults than the snobby condescension and “tolerance” of camp enchantment—which, as its own name suggests, is the way Cheezy Flicks chooses to hawk its wares. (When Franju’s no less fragile Judex received its New York release in the wake of Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” I can still recall the crudity with which the press and publicity strove to vulgarize and oversimplify that essay in the process of making dull stabs at a “camp appreciation,” besmirching both Sontag and Franju in the process.)

Mysterious Island. I’m talking about the 15-chapter serial of 1951, directed by Spencer Bennet (and available for a mere $7.99 from cheezyflicks.com, less than half of what Amazon charges), not the Cy Endfield/Ray Harryhausen blunderbuss of a decade later. Even though part of my enthusiasm is nostalgia for the unadulterated pleasure this low-budgeter gave me when I was eight years old, I would still maintain that the delicacy and tenderness of this Victorian, Verne-derived adventure are worth a lot more to adults than the snobby condescension and “tolerance” of camp enchantment—which, as its own name suggests, is the way Cheezy Flicks chooses to hawk its wares. (When Franju’s no less fragile Judex received its New York release in the wake of Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” I can still recall the crudity with which the press and publicity strove to vulgarize and oversimplify that essay in the process of making dull stabs at a “camp appreciation,” besmirching both Sontag and Franju in the process.)

Starting with the first chapter—in which a Confederate puppy befriends a Yankee officer (Richard Crane), who soon afterwards gets reunited with his black servant (Bernard Hamilton) and is joined by a war correspondent, a sailor, and the latter’s adopted son in a runaway balloon, which is carried by a storm to an island populated by native volcano worshippers with lightning-shaped spears, along with a drum majorette from Mercury named Rulu (Karen Randle) with a ray-gun and black-cloaked assistants—Mysterious Island already signals a desire to step, and even live, beyond the usual tribal categories and divisions. Indeed, the character played by Hamilton (who would later co-star effectively in Buñuel’s 1960 The Young One, before winding up as Capt. Harold Dobey on Starsky and Hutch) is treated with at least as much respect and courtesy as Sir Lancelot in Val Lewton’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943) and The Curse of the Cat People (1944). Like Jim in Huckleberry Finn, he’s even ahead of the white characters in figuring out what’s going on much of the time—and for whatever it’s worth, I can’t imagine that the white, Jim Crow audience I saw this serial with minded this peculiarity in the slightest.

Best of all, in contrast to the more primitive, preadolescent complacencies of such tub-thumping shlockmeisters as George Lucas, John McCain, and Quentin Tarantino, in their boringly unvarying divisions of the universe between “good guys” and “bad guys,” all of the putative villains here—the Volcano People, the Wild Man, a motley crew of pirates, even the Mercuryian dominatrix in hot pants—periodically become (or else simply wind up as) allies of the heroes. (They’re also engagingly pragmatic in other ways: one key line in the final episode is Rulu’s “This is no time for a battle. We have more important things to do.”) This suggests a casual moral fluidity that seems to belong to a civilization significantly more advanced and relaxed than ours, despite the fact that 1951 is supposed to be the very apex of Cold War paranoia. In other words, this is a movie about getting along rather than one about empire-building, which makes it particularly relevant to the present. I’m sure that some of this must be attributable to Verne, but wherever it comes from, it’s more than welcome.

Back on the empire-building front: John Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) is one of the two recent Twilight Time Blu-ray releases from Darryl F. Zanuck’s Fox whose Technicolor is so jaw-dropping that one is periodically persuaded to overlook all sorts of dramaturgical and/or ideological excesses. (The other is John M. Stahl’s 1945 Leave Her to Heaven, arguably the most luscious-looking of all colour noirs.) Drums was in fact Ford’s first colour film, and is clearly one of his most beautiful pictorially, if also one of his most objectionable when it comes to racial stereotyping. (The first appearance of a Native American—who turns out to be a comic buffoon, even if he sends Claudette Colbert’s terrified frontier wife into endless bouts of hysterics—is lit as if Ford were trying to outdo Universal Pictures for sheer Gothic horror.) This splendid Blu-ray also comes with Nick Redman’s feature-length Becoming John Ford (2007), about the partnership between Ford and Zanuck, as well as a factually and historically rich audio commentary by Redman and Twilight Time regular Julie Kirgo, the latter of whom also provides an essay.

Back on the empire-building front: John Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) is one of the two recent Twilight Time Blu-ray releases from Darryl F. Zanuck’s Fox whose Technicolor is so jaw-dropping that one is periodically persuaded to overlook all sorts of dramaturgical and/or ideological excesses. (The other is John M. Stahl’s 1945 Leave Her to Heaven, arguably the most luscious-looking of all colour noirs.) Drums was in fact Ford’s first colour film, and is clearly one of his most beautiful pictorially, if also one of his most objectionable when it comes to racial stereotyping. (The first appearance of a Native American—who turns out to be a comic buffoon, even if he sends Claudette Colbert’s terrified frontier wife into endless bouts of hysterics—is lit as if Ford were trying to outdo Universal Pictures for sheer Gothic horror.) This splendid Blu-ray also comes with Nick Redman’s feature-length Becoming John Ford (2007), about the partnership between Ford and Zanuck, as well as a factually and historically rich audio commentary by Redman and Twilight Time regular Julie Kirgo, the latter of whom also provides an essay.

Two other recent Twilight Time releases worth noting—both (again) accompanied by Kirgo essays, but without audio commentaries or any other extras apart from the original trailers—are Fritz Lang’s scorching 1953 masterpiece The Big Heat, exceptional both as social commentary and as a showcase for its cast (especially Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame, and Lee Marvin), and Louis Malle’s far more modest but still watchable and potent 1985 Alamo Bay, which I saw for the first time, and is especially notable for a strong Amy Madigan performance.

Two other recent Twilight Time releases worth noting—both (again) accompanied by Kirgo essays, but without audio commentaries or any other extras apart from the original trailers—are Fritz Lang’s scorching 1953 masterpiece The Big Heat, exceptional both as social commentary and as a showcase for its cast (especially Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame, and Lee Marvin), and Louis Malle’s far more modest but still watchable and potent 1985 Alamo Bay, which I saw for the first time, and is especially notable for a strong Amy Madigan performance.

Every Twilight Time Blu-ray is a class act, even when one doesn’t like the picture, but when it comes to sorting out the far more plentiful Blu-ray releases from Olive Films, not all of which I can bring myself to watch, I feel many of the times I approach a new selection that I’m dealing with a pig in a poke. The issue isn’t so much the almost unvarying absence of extras as the seeming absence of any discernible selection process—namely, what titles do they choose to pass up? Some of their latest offerings include Edward Dehn’s 1955 Shack Out on 101 (Commie spies in a diner, including Lee Marvin and Frank Lovejoy, duking it out with Terry Moore and Keenan Wynn), and William Castle’s The Americano from the same year, which stars Glenn Ford as a Texas bull rancher who travels to the Brazilian backwoods to close a sale and winds up tangling with Cesar Romero as a cackling and “colourful” bandit (a part that would have normally gone to Anthony Quinn), Frank Lovejoy as a friendly colonialist fanatic, and Latin hotcakes Ursula Thiess and Abbe Lane (the latter actually belting out a number at one point with the invisible support of her hubby Xavier Cugat in a remote village, with native musicians). Neither film is devoid of interest (even if the poor editing of archival footage into the action of The Americano sometimes drives me batty), and the same goes for Hubert Cornfield’s 1957 Plunder Road, a road movie/heist thriller in black-and-white ’Scope which boasts a fancy turn by Elisha Cook, Jr. But the overall sensation that I’m stumbling upon these movies rather than following anyone’s politique is fairly constant, and when it comes to a release such as the stupefying 1945 rom-com Guest Wife, directed by Sam Wood (or “the great Sam Wood,” as the blurb on the back of the box has it), I can only balk in disbelief.

Every Twilight Time Blu-ray is a class act, even when one doesn’t like the picture, but when it comes to sorting out the far more plentiful Blu-ray releases from Olive Films, not all of which I can bring myself to watch, I feel many of the times I approach a new selection that I’m dealing with a pig in a poke. The issue isn’t so much the almost unvarying absence of extras as the seeming absence of any discernible selection process—namely, what titles do they choose to pass up? Some of their latest offerings include Edward Dehn’s 1955 Shack Out on 101 (Commie spies in a diner, including Lee Marvin and Frank Lovejoy, duking it out with Terry Moore and Keenan Wynn), and William Castle’s The Americano from the same year, which stars Glenn Ford as a Texas bull rancher who travels to the Brazilian backwoods to close a sale and winds up tangling with Cesar Romero as a cackling and “colourful” bandit (a part that would have normally gone to Anthony Quinn), Frank Lovejoy as a friendly colonialist fanatic, and Latin hotcakes Ursula Thiess and Abbe Lane (the latter actually belting out a number at one point with the invisible support of her hubby Xavier Cugat in a remote village, with native musicians). Neither film is devoid of interest (even if the poor editing of archival footage into the action of The Americano sometimes drives me batty), and the same goes for Hubert Cornfield’s 1957 Plunder Road, a road movie/heist thriller in black-and-white ’Scope which boasts a fancy turn by Elisha Cook, Jr. But the overall sensation that I’m stumbling upon these movies rather than following anyone’s politique is fairly constant, and when it comes to a release such as the stupefying 1945 rom-com Guest Wife, directed by Sam Wood (or “the great Sam Wood,” as the blurb on the back of the box has it), I can only balk in disbelief.

(I hasten to add that a lack of selectivity can sometimes be a defensible and even honourable position, especially if one isn’t presuming to outguess the tastes and biases of the future. When I moved to Paris in 1969, I recall that some of the daily programs at the Cinémathèque française selected by Henri Langlois followed the same general principles of arbitrariness, occasionally—if not often—with fruitful results. But there are times when I wonder if in Olive’s case this is anything more than an indifferent default position rather than some form of curiosity.)

Spurred on by Dave Kehr’s excellent DVD column in the New York Times, I also checked out the two Gordon Douglas black-and-white features recently released by Olive, the James Cagney gangster flick Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950) and the Gregory Peck cavalry-vs.-Apache western Only the Valiant (1951). Kehr praised both while privileging the former, but it was the weird and lesser-known latter film that caught more of my attention—consistently unpredictable and offbeat, it was berated by Peck as one of his worst films, perhaps because the character he plays in it is so atypically uncharismatic.

Spurred on by Dave Kehr’s excellent DVD column in the New York Times, I also checked out the two Gordon Douglas black-and-white features recently released by Olive, the James Cagney gangster flick Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950) and the Gregory Peck cavalry-vs.-Apache western Only the Valiant (1951). Kehr praised both while privileging the former, but it was the weird and lesser-known latter film that caught more of my attention—consistently unpredictable and offbeat, it was berated by Peck as one of his worst films, perhaps because the character he plays in it is so atypically uncharismatic.

Let me consider one other recent Olive release, watched soon after writing the above, which confounds many of the arguments I’ve just stated: their Blu-ray of Playing for Time (1980), a powerful teleplay by Arthur Miller directed by Daniel Mann and starring Vanessa Redgrave (in what may be her greatest on-screen performance), which comes with a passionately polemical, as well as informative, 42-page essay by film academic Terri Ginsberg that’s one of the most interesting and compelling critical texts I’ve encountered on any digital release. (The same essay came with the DVD, released in 2010, according to Gary Tooze’s rave review of the latter at his DVD Beaver site.) Put simply, the release of this film with this essay is nothing if not selective and purposeful, and it deserves our deepest thanks. It even makes up for all the more dubious Olive releases without any extras or explanations.

Let me consider one other recent Olive release, watched soon after writing the above, which confounds many of the arguments I’ve just stated: their Blu-ray of Playing for Time (1980), a powerful teleplay by Arthur Miller directed by Daniel Mann and starring Vanessa Redgrave (in what may be her greatest on-screen performance), which comes with a passionately polemical, as well as informative, 42-page essay by film academic Terri Ginsberg that’s one of the most interesting and compelling critical texts I’ve encountered on any digital release. (The same essay came with the DVD, released in 2010, according to Gary Tooze’s rave review of the latter at his DVD Beaver site.) Put simply, the release of this film with this essay is nothing if not selective and purposeful, and it deserves our deepest thanks. It even makes up for all the more dubious Olive releases without any extras or explanations.

Two new DVDs from another label, Lionsgate, both of films that I’ve just seen for the first time, Jeff Nichols’ Mud and Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell. Both certainly held my interest, above all as storytelling, and Mud also boasts some colourful Arkansas scenery. But it’s Stories We Tell that really bowled me over, not only because it fulfills the promise of Polley’s first feature Away From Her (2006), but also because it’s like a sister film in some respects to one of my continuing favourites, Françoise Romand’s mind-boggling 1985 Mix-up (still available from Amazon, by the way). Like Polley’s film, Mix-up is an artful blend of fiction and non-fiction, a therapeutic unpacking of family dysfunction via recountings and re-enactments with a novelistic density, at once playful and profound—with the significant difference that Polley is unpacking her own family history and origins, including the fact that both her parents were also actors, which complicates the role-playing and fiction-mongering still further.

Believing for a spell that I would be teaching a weekly course called “World Cinema of the 1930s” at the University of Chicago’s Graham School last fall (until only four people signed up for it, which led to a cancellation), I ordered more viewable editions of Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934) and Mizoguchi Kenji’s The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939). The first of these was included in The Bela Lugosi Collection from Universal, which squeezes five features onto both sides of a single DVD—which is fine if the results are playable, but in my case The Black Cat started to become unplayable about halfway through, which led me to purchase an okay second copy of the set. I had better luck with The Mizoguchi Collection from Artificial Eye UK, which includes Osaka Elegy (1936), Sisters of the Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, and Utamaro and His [sic] Five Women (1946), each on a separate disc.

Believing for a spell that I would be teaching a weekly course called “World Cinema of the 1930s” at the University of Chicago’s Graham School last fall (until only four people signed up for it, which led to a cancellation), I ordered more viewable editions of Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934) and Mizoguchi Kenji’s The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939). The first of these was included in The Bela Lugosi Collection from Universal, which squeezes five features onto both sides of a single DVD—which is fine if the results are playable, but in my case The Black Cat started to become unplayable about halfway through, which led me to purchase an okay second copy of the set. I had better luck with The Mizoguchi Collection from Artificial Eye UK, which includes Osaka Elegy (1936), Sisters of the Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, and Utamaro and His [sic] Five Women (1946), each on a separate disc.

Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Love and a Time to Die (Masters of Cinema Blu-ray). If I’m not mistaken, all of the extras on this Region 2 release come from elsewhere, including the redundancy of a 12-minute French short needlessly “reading” Godard’s celebrated contemporary review of the film, which is already included in the 36-page booklet. But even if one has to put up with splotchy clips and frame enlargements from Sirk’s films in the three documentaries here, including a 19-minute interview with Wesley Strick, this is more than worth it when it comes to Daniel Schmid’s 51-minute interview with Sirk from 1984. The latter seems drawn from two separate sessions, both enlisting further remarks from Sirk’s actress wife at what appears to be their retirement home in Switzerland, with the maestro discoursing obscurely and profoundly on such topics as his aesthetic distaste for Nazis, his interlude as a chicken farmer in the US before he began his second career as a film director, some theoretical remarks about death, circles, and morality or its absence, and a recitation of a Goethe poem that he knows by heart and obviously relishes (and which Craig Keller reproduces, both in German and with his own English translation, in the booklet). I’m still awaiting a DVD and/or Blu-ray of my favourite Sirk feature, the dazzling 1936 Schlussakkord (another film I planned to show in my “World Cinema of the 1930s” course), but in the meantime, the CinemaScope rendering of his most personal Hollywood feature seems impeccable.

Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Love and a Time to Die (Masters of Cinema Blu-ray). If I’m not mistaken, all of the extras on this Region 2 release come from elsewhere, including the redundancy of a 12-minute French short needlessly “reading” Godard’s celebrated contemporary review of the film, which is already included in the 36-page booklet. But even if one has to put up with splotchy clips and frame enlargements from Sirk’s films in the three documentaries here, including a 19-minute interview with Wesley Strick, this is more than worth it when it comes to Daniel Schmid’s 51-minute interview with Sirk from 1984. The latter seems drawn from two separate sessions, both enlisting further remarks from Sirk’s actress wife at what appears to be their retirement home in Switzerland, with the maestro discoursing obscurely and profoundly on such topics as his aesthetic distaste for Nazis, his interlude as a chicken farmer in the US before he began his second career as a film director, some theoretical remarks about death, circles, and morality or its absence, and a recitation of a Goethe poem that he knows by heart and obviously relishes (and which Craig Keller reproduces, both in German and with his own English translation, in the booklet). I’m still awaiting a DVD and/or Blu-ray of my favourite Sirk feature, the dazzling 1936 Schlussakkord (another film I planned to show in my “World Cinema of the 1930s” course), but in the meantime, the CinemaScope rendering of his most personal Hollywood feature seems impeccable.

There’s another and even better Sirk classic, The Tarnished Angels (1958), out on a separate Masters of Cinema Blu-ray. It hardly needs any recommendation from me, but here’s a juicy and fascinating (if rambling and slightly distracted) tidbit from a 1958 William Faulkner interview included in the accompanying 44-page booklet: “Some good pictures come from out there [Hollywood]. One of my favourites was Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons—and High Noon, whatever became of that? Television? You don’t say. That’s all you need for a good story: a man doin’ something he has to do, against himself and against his environment. Not courage, necessarily.” (I assume he’s describing Gary Cooper’s sheriff, but theoretically he could also be describing Kane’s title hero and Ambersons’ Tim Holt or Joseph Cotten.)

There’s another and even better Sirk classic, The Tarnished Angels (1958), out on a separate Masters of Cinema Blu-ray. It hardly needs any recommendation from me, but here’s a juicy and fascinating (if rambling and slightly distracted) tidbit from a 1958 William Faulkner interview included in the accompanying 44-page booklet: “Some good pictures come from out there [Hollywood]. One of my favourites was Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons—and High Noon, whatever became of that? Television? You don’t say. That’s all you need for a good story: a man doin’ something he has to do, against himself and against his environment. Not courage, necessarily.” (I assume he’s describing Gary Cooper’s sheriff, but theoretically he could also be describing Kane’s title hero and Ambersons’ Tim Holt or Joseph Cotten.)

- « Previous

- 1

- 2