Global Discoveries on DVD: Niche Market Refugees

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Let me start with a correction and adjustment to the final entry in my last column, furnished by Chris Fujiwara and relating to the appearance of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 131-minute The Honey Pot (1967) on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray:

“When I did my stint at the Frieda Grafe favorite films series at Arsenal in Berlin two or three years ago, they showed a good 35mm print of The Honey Pot that ran about 150 minutes. It had a BBFC (British Board of Film Censors) card on it and it came from Park Circus. (By the way I took detailed notes of the differences from the DVD version, which I had recently watched several times.)…The cutting that was done to the film to get it down to 131 minutes was quite extensive and elaborate. In a few cases whole scenes were cut out (including scenes with the three ex-lovers, and a scene showing Cliff Robertson at work as a male escort). But a good deal of the shortening was done by cutting out individual shots or parts of shots from scenes that are otherwise kept in. Not only the rhythm but also the tone and the thematic content of these scenes are changed, sometimes drastically…It’s a very good film in the short version, but watching the longer version I became convinced it was great.”

As a Frieda Grafe fan who participated in the same Arsenal program (introducing Billy Wilder’s similarly neglected Avanti! [1972]) and who also treasures her brilliant and singular monograph on Mankiewicz’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) in the BFI Film Classics series, I promptly went looking for a 150-minute version of The Honey Pot on the internet, and discovered on eBay a moderately priced Region 4 DVD that claimed to run that long, which I ordered. Not surprisingly, this proved to be a futile gesture and most likely a case of lazy or indifferent mendacity: the Australian DVD claims to be “approximately 150 minutes,” but is in fact only 126. But meanwhile, I was both pleased and amused to read in Cheryl Bray Lower’s remarks about The Honey Pot (in her 2001 book Joseph L. Mankiewicz, co-authored with R. Barton Palmer) that the name of Rex Harrison’s character, “Cecil Fox,” alludes not only to the movie’s major source—Ben Jonson’s Volpone, whose title means “fox” in Italian—but also to the studio where Mankiewicz prospered and perished for most of his career between Dragonwyck (1946) and Cleopatra (1963). This seems almost as funny and as apt as the brief moment when Stephen McNally’s chief medical resident in Mankiewicz’s No Way Out (1950), a principled and unprejudiced good guy, reveals in passing that he doesn’t remember the surname of his black maid, whom he’s employed for decades.

***

Three very different kinds of exceptional hokum can be found in the second volume of Fox Horror Classics on DVD, which consists of Mankiewicz’s aforementioned Dragonwyck, Marcel Varnel and William Cameron Menzies’ Chandu the Magician (1932), and Harry Lachman’s Dr. Renault’s Secret (1942) on separate discs, all of which I’ve just seen for the first time. Truthfully, the only exceptional aspect of the last of these—a fairly routine 58-minute B feature that’s basically a murder mystery with a French provincial setting, dimly derived from a Gaston Leroux source—is J. Carrol Naish’s touching performance as an apeman.

Three very different kinds of exceptional hokum can be found in the second volume of Fox Horror Classics on DVD, which consists of Mankiewicz’s aforementioned Dragonwyck, Marcel Varnel and William Cameron Menzies’ Chandu the Magician (1932), and Harry Lachman’s Dr. Renault’s Secret (1942) on separate discs, all of which I’ve just seen for the first time. Truthfully, the only exceptional aspect of the last of these—a fairly routine 58-minute B feature that’s basically a murder mystery with a French provincial setting, dimly derived from a Gaston Leroux source—is J. Carrol Naish’s touching performance as an apeman.

The real find in the bunch, and also the hokiest, is Chandu, especially memorable for Menzies’ fabulous production design and special effects (Varnel was essentially around to direct the actors)—although Bela Lugosi fans certainly won’t be disappointed, and even the dopiest period standbys (lots of Prohibition humour about the alcoholism of the comic relief and his diverse hallucinations) have their enduring charms. This energetic adventure, based on a popular radio serial, is so obscure that even such a specialist as the late Elliott Stein didn’t think of including it in the extensive Menzies credits of his revised and expanded edition of Léon Barsacq’s Caligari’s Cabinet and Other Grand Illusions: A History of Film Design. But it’s every bit as juicy as The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) in its unbridled magnificence, and for my money, far more likable than the Indiana Jones movies derived from its crazed fantasies.

Mankiewicz’s first feature, well served by an extensively researched audio commentary from Steve Haberman and Constantine Nasr, is a pre-feminist Gothic featuring Vincent Price’s best performance (apparently he thought so too) and a lot of well-dressed period flavour. It’s also more of a personal effort than it’s usually cracked up to be, even though Jean-Luc Godard, in his first published film review, was fairly dismissive of its overheated melodrama before going on to praise Mankiewicz’s later Somewhere in the Night (1946), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, A Letter to Three Wives, and House of Strangers (both 1949) as the work of a genuine auteur. Haberman and Nasr are especially good in outlining what drove Ernst Lubitsch to remove his producer’s credit from the picture (a move seemingly motivated by studio’s removal of anti-Nazi material, with Mankiewicz’s apparent consent), although I wish they’d amplified or complicated their account by mentioning that he and Mankiewicz were both Jewish and Darryl F. Zanuck wasn’t.

***

If distant memory serves, the last time that I saw Giuseppe De Santis’ Bitter Rice (1949) before Criterion’s excellent Blu-ray turned up, I was still in grammar school in Alabama, or not much older than that. And if I misremembered the film as being in colour, this was undoubtedly due to the erotic power of those juicy posters with Silvana Mangano in the rice paddy; I’d forgotten about the crime melodrama lurking in the background, making this, as the Criterion packaging aptly has it, “neorealism with a heaping dose of pulp.” But I’m grateful for this refresher course, which includes screenwriter Carlo Lizzani’s lovely 2008 documentary about De Santis (whose 1952 Rome 11 O’Clock I’d also seen in Alabama, and which I hope Criterion will also consider releasing) as well as a 2002 interview with Lizzani about the film’s production. The latter is especially notable for its persuasive riposte to Luc Moullet’s remark (in his 1958 review of Jet Pilot) that “it seems that erotic verve would be indissociable from contempt for every collectivity” by offering us a series of seemingly incompatible binaries—communism and Mangano’s volcanic fleshiness, social protest and Manichean melodrama, collectivity and Hollywood pizzazz—with equal amounts of verve and force.

If distant memory serves, the last time that I saw Giuseppe De Santis’ Bitter Rice (1949) before Criterion’s excellent Blu-ray turned up, I was still in grammar school in Alabama, or not much older than that. And if I misremembered the film as being in colour, this was undoubtedly due to the erotic power of those juicy posters with Silvana Mangano in the rice paddy; I’d forgotten about the crime melodrama lurking in the background, making this, as the Criterion packaging aptly has it, “neorealism with a heaping dose of pulp.” But I’m grateful for this refresher course, which includes screenwriter Carlo Lizzani’s lovely 2008 documentary about De Santis (whose 1952 Rome 11 O’Clock I’d also seen in Alabama, and which I hope Criterion will also consider releasing) as well as a 2002 interview with Lizzani about the film’s production. The latter is especially notable for its persuasive riposte to Luc Moullet’s remark (in his 1958 review of Jet Pilot) that “it seems that erotic verve would be indissociable from contempt for every collectivity” by offering us a series of seemingly incompatible binaries—communism and Mangano’s volcanic fleshiness, social protest and Manichean melodrama, collectivity and Hollywood pizzazz—with equal amounts of verve and force.

***

Speaking to Michel Ciment, Joseph Losey said that he regarded Figures in a Landscape as “a marvelous title,” but I should confess that it was this title that kept me away from Losey’s 1970 film for 45 years: I was afraid of colliding with something arty and allegorical, and I can see now that my fears were entirely justified. But now that a Kino Lorber Blu-ray has allowed me to see the film in all its 2.35:1 splendour, I find that the only marvellous bits in it—and they really are marvellous—are precisely the moments that justify the title. Whenever the eponymous figures—Robert Shaw and Malcolm McDowell, playing fugitives on the run in an unnamed totalitarian country—have to function as characters in a story, I can’t fathom what’s going on and I couldn’t care less about arriving at any understanding. (How does Shaw manage to kill a goatherd offscreen when his hands are still tied behind his back? Who or what are he and McDowell fleeing from, and why? What do their edgy, pseudo-Pinteresque dialogues signify? And most of all, why should I be interested in answering these questions?) But whenever they’re being chased around and across Spanish landscapes by helicopters, I’m thrilled by Losey’s mise en scène and the cinematography (most of it by Henri Alekan); I also like the unabashedly arty score by Richard Rodney Bennett, which does as much with and for the spectacular landscapes and camera movements as the actors. While it’s interesting that Shaw also wrote the script (adapted from what Losey plausibly describes as a repulsive novel), for me it’s the shots and the action that make this worth seeing, not the strained narrative pretexts for putting them all together.

Speaking to Michel Ciment, Joseph Losey said that he regarded Figures in a Landscape as “a marvelous title,” but I should confess that it was this title that kept me away from Losey’s 1970 film for 45 years: I was afraid of colliding with something arty and allegorical, and I can see now that my fears were entirely justified. But now that a Kino Lorber Blu-ray has allowed me to see the film in all its 2.35:1 splendour, I find that the only marvellous bits in it—and they really are marvellous—are precisely the moments that justify the title. Whenever the eponymous figures—Robert Shaw and Malcolm McDowell, playing fugitives on the run in an unnamed totalitarian country—have to function as characters in a story, I can’t fathom what’s going on and I couldn’t care less about arriving at any understanding. (How does Shaw manage to kill a goatherd offscreen when his hands are still tied behind his back? Who or what are he and McDowell fleeing from, and why? What do their edgy, pseudo-Pinteresque dialogues signify? And most of all, why should I be interested in answering these questions?) But whenever they’re being chased around and across Spanish landscapes by helicopters, I’m thrilled by Losey’s mise en scène and the cinematography (most of it by Henri Alekan); I also like the unabashedly arty score by Richard Rodney Bennett, which does as much with and for the spectacular landscapes and camera movements as the actors. While it’s interesting that Shaw also wrote the script (adapted from what Losey plausibly describes as a repulsive novel), for me it’s the shots and the action that make this worth seeing, not the strained narrative pretexts for putting them all together.

Figures in a Landscape whetted my appetite for more of Losey’s baroque mise en scène, which led me to revisit both Eva (1962) online as an Amazon video and The Servant (1962) on my long-out-of-print DVD, where I discovered a comparable split between stylistic brio of a similar sort waged against another panoply of sadomasochistic power struggles. Admittedly, the power struggles in these earlier films seem far more substantial in relation to class and psychosexual personal investments (which make them far less formalistic than the overt allegorizing of Figures), and the galvanizing star presences of Dirk Bogarde, James Fox, Sarah Miles, and Wendy Craig in The Servant make it easier to accept the schematic improbabilities of their characters. But the challenge of reconciling sadomasochism with a Marxist social analysis is arguably just as problematic in these two films as it is in Fassbinder’s films a decade or more later. Both features have impressive but obtrusive jazz scores (by Michel Legrand and Johnny Dankworth, respectively) that seem designed to smother or at least simplify the intellectual issues with emotional bombast, and the almost abject reliance on Antonioni’s notions of decadence (especially strident in Eva) makes the arabesques of the camera movements not so much circles around a void as pirouettes around a borrowed void. These are the two films that consolidated and established Losey’s permanent shift from genre movies to art films—although I suppose Figures in a Landscape can be regarded as Losey’s belated attempt to perform a shotgun marriage between these disparate modes—but to my taste, Losey’s most exciting film of the ’60s and maybe even his best film altogether remains the far less fashionable The Damned (a.k.a. These Are the Damned, 1961), made just before Eva, which I wrote about in this column a little over five years ago. (Go to cinema-scope.com/columns/columns-global-discoveries-on-dvd-assorted-lessons-from-the-past-and-present/.)

Figures in a Landscape whetted my appetite for more of Losey’s baroque mise en scène, which led me to revisit both Eva (1962) online as an Amazon video and The Servant (1962) on my long-out-of-print DVD, where I discovered a comparable split between stylistic brio of a similar sort waged against another panoply of sadomasochistic power struggles. Admittedly, the power struggles in these earlier films seem far more substantial in relation to class and psychosexual personal investments (which make them far less formalistic than the overt allegorizing of Figures), and the galvanizing star presences of Dirk Bogarde, James Fox, Sarah Miles, and Wendy Craig in The Servant make it easier to accept the schematic improbabilities of their characters. But the challenge of reconciling sadomasochism with a Marxist social analysis is arguably just as problematic in these two films as it is in Fassbinder’s films a decade or more later. Both features have impressive but obtrusive jazz scores (by Michel Legrand and Johnny Dankworth, respectively) that seem designed to smother or at least simplify the intellectual issues with emotional bombast, and the almost abject reliance on Antonioni’s notions of decadence (especially strident in Eva) makes the arabesques of the camera movements not so much circles around a void as pirouettes around a borrowed void. These are the two films that consolidated and established Losey’s permanent shift from genre movies to art films—although I suppose Figures in a Landscape can be regarded as Losey’s belated attempt to perform a shotgun marriage between these disparate modes—but to my taste, Losey’s most exciting film of the ’60s and maybe even his best film altogether remains the far less fashionable The Damned (a.k.a. These Are the Damned, 1961), made just before Eva, which I wrote about in this column a little over five years ago. (Go to cinema-scope.com/columns/columns-global-discoveries-on-dvd-assorted-lessons-from-the-past-and-present/.)

***

The last time I looked, Anne Bancroft’s Fatso (1980), the actress’ only feature as a director, was available from Amazon for $123.95 (“only one left in stock—order soon”), with 30 more “new or used” offers ranging from $59.98 (used) to $174.99 (used). I interpret these exorbitant prices as an indication that the movie flopped so badly when it came out that it’s become a “cult” or niche-market item—undesired by most people, but passionately valued by a few. Not feeling myself necessarily in either category, I saw it recently for the first time on cable TV (RetroPLEX) and liked it pretty much, enough to regret that Bancroft’s filmmaking oeuvre ended here.

The last time I looked, Anne Bancroft’s Fatso (1980), the actress’ only feature as a director, was available from Amazon for $123.95 (“only one left in stock—order soon”), with 30 more “new or used” offers ranging from $59.98 (used) to $174.99 (used). I interpret these exorbitant prices as an indication that the movie flopped so badly when it came out that it’s become a “cult” or niche-market item—undesired by most people, but passionately valued by a few. Not feeling myself necessarily in either category, I saw it recently for the first time on cable TV (RetroPLEX) and liked it pretty much, enough to regret that Bancroft’s filmmaking oeuvre ended here.

As we all know, advertising taglines have a lot to do with what can make or break a movie once it surfaces, and a clear explanation of why Fatso flopped at the box office can be found in Roger Ebert’s one-star review, excerpted below:

“Two basic dramatic approaches to fatness are to regard it as comic, or tragic. Anne Bancroft has somehow avoided both approaches in Fatso, a movie with the unique distinction of creating in its audiences an almost constant suspense about how they’re supposed to be reacting. The movie itself just doesn’t know: Fatso has a director, a screenplay, and a cast who are all uncertain about how they really feel about overweight.

“…There’s a key moment when it’s clear that [three] fatsos are about to break down [from their group weight-losing regime]. The movie has a quick edit to them stirring up a bowl of chocolate frosting. That could have cued us to laugh, if the edit had been to a close-up, say, of [Dom] DeLuise licking the spoon. But what camera position does Bancroft choose for the cut? She puts her camera directly overhead in the kitchen, and shoots straight down!…She couldn’t have done a better job of finding a camera angle that leaves us totally at sea.”

In fact, Bancroft’s approach to the film as writer-director and co-star, fully supported by the remainder of her cast, is comic and tragic—creating a kind of uncertainty about immediate responses that Ebert is absolutely right to pinpoint (we neither laugh nor cry), but completely wrong to deem out of bounds. Born Anna Maria Louisa Italiano in the Bronx, Bancroft is clearly working out of deeply autobiographical and personal material that, like her characters, she confronts both obsessively and ambivalently, but by no means indecisively (the personal element is even intensified by her naming DeLuise’s not-so-fat hero “Dom”). As the Italian immigrant milieu makes clear from the outset, eating a lot qualifies as both a celebration of life and as a health hazard, and Bancroft insists on keeping both conditions in constant play throughout, settling on the first over the second only after romance enters and eventually overtakes the picture, and then decisively only when she arrives at the film’s final credits, as a kind of cheerful afterthought. “You got crazy blood in your brains,” Dom’s aunt (played by Bancroft) hysterically exclaims to Dom at one climactic juncture, and the movie bears this out at every turn, embracing and denouncing that craziness with equal amounts of fervour.

As Bancroft is interested in both implicating the audience in her hero’s struggle and objectifying the results at the same time, the overhead camera angle that Ebert objected to is in fact perfectly chosen, because it’s the only angle that can fully reveal all the dishes and other receptacles that carry the ravages of her trio’s manic eating binge. Like the earlier sequence that shows Dom restlessly switching TV channels in order to distract himself from his compulsive food fantasies—only to find that they’re all catering to the same impulses—in this shot Bancroft is zeroing in on consumption as a quintessential American issue, too complex and multifaceted to be encompassed by either comedy or tragedy in isolation from one another. In short, I think it could be argued that Fatso failed commercially only because of the scope of its ambitions.

***

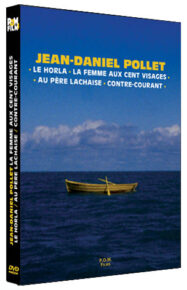

In the first of my Paris Journals written for Film Comment (Fall 1971), the two films that excited me the most at the time, both of which I was belatedly catching up with, were two tales about encroaching madness: Jean-Daniel Pollet’s 37-minute Le Horla (1966) and Jacques Rivette’s 252-minute L’amour fou (1968), each of which excels in a very different way through its groundbreaking treatment of time. The latter of these remains woefully unavailable on DVD or Blu-ray, but the former (starring Laurent Terzieff, the only actor in the film) can now be found on DVD via French Amazon, along with three other Pollet shorts—La Femme aux cent visages (1968) Au Père Lachaise (1986), and Contre-Courant (1991)—and several extras, including an extended interview with Jean-Luc Godard titled JDP/JLG. There are no English subtitles for the film or any of the supplements, but in the case of Le Horla, you can manage just fine if you read the Guy de Maupassant story on which it is based (and which comprises the only text in the film) in English at www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/Horl.shtml; and as far as the Godard interview is concerned, he mainly seems to be preoccupied with Pollet’s far more famous (but to me less interesting) 44-minute Méditerranée (1963), available on a separate DVD in the same Pollet collection, and with its text by Philippe Sollers. (Still another DVD in this series, which I also have and treasure, is Pollet’s 90-minute essay film Dieu sait quoi [1994], an homage to the extraordinary prose poet Francis Ponge, which has far more relevance, plastically and rhythmically, to the brilliance of Le Horla than does Méditerranée.)

In the first of my Paris Journals written for Film Comment (Fall 1971), the two films that excited me the most at the time, both of which I was belatedly catching up with, were two tales about encroaching madness: Jean-Daniel Pollet’s 37-minute Le Horla (1966) and Jacques Rivette’s 252-minute L’amour fou (1968), each of which excels in a very different way through its groundbreaking treatment of time. The latter of these remains woefully unavailable on DVD or Blu-ray, but the former (starring Laurent Terzieff, the only actor in the film) can now be found on DVD via French Amazon, along with three other Pollet shorts—La Femme aux cent visages (1968) Au Père Lachaise (1986), and Contre-Courant (1991)—and several extras, including an extended interview with Jean-Luc Godard titled JDP/JLG. There are no English subtitles for the film or any of the supplements, but in the case of Le Horla, you can manage just fine if you read the Guy de Maupassant story on which it is based (and which comprises the only text in the film) in English at www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/Horl.shtml; and as far as the Godard interview is concerned, he mainly seems to be preoccupied with Pollet’s far more famous (but to me less interesting) 44-minute Méditerranée (1963), available on a separate DVD in the same Pollet collection, and with its text by Philippe Sollers. (Still another DVD in this series, which I also have and treasure, is Pollet’s 90-minute essay film Dieu sait quoi [1994], an homage to the extraordinary prose poet Francis Ponge, which has far more relevance, plastically and rhythmically, to the brilliance of Le Horla than does Méditerranée.)

To quote from my 1971 column, “Pollet has indicated in an interview that his interest in the project was not so much de Maupassant’s horror story itself but the problem of integrating the text into a cinematic structure. Part of his solution is to maintain a fluid continuity in the spoken first-person narration while locating this discourse through montage in three alternating ‘relative’ tenses: past (the plot unfolding beneath the narration), present (the narrator recounting the action into a tape recorder), and future (the tape recorder playing his voice in an abandoned rowboat). Thus while the story’s chronology and continuity are respected, the montage enables the film to achieve a semi-autonomous achronological structure of its own, and the tensions between these coexisting forms produces some extraordinary effects—effects, moreover, which serve the original story admirably, enclosing its intimations of possession and madness in a rigid continuum of haunting finality. Equally striking is a bold thematic use of color, with the richest blues this side of Pierrot le fou.”

Even more, the solitary hero’s crazed intimations of an invisible doppelgänger lurking nearby and waiting to replace him, even reading the same texts over his shoulders, are neatly and eerily replicated by the camera’s own positions and activities, and the hero’s fear of being supplanted by the monster seems borne out by the way that the tape recorder replaces Terzieff in the otherwise empty rowboat.

***

What’s most delightful about Françoise Romand’s new feature, Baiser d’encre (Ink Kiss)—available on an all-region DVD (with extras and optional English, French, and Spanish subtitles) from romand.org—is how the work and life of an inspired hippie-artist couple, Ella and Pitr, who “paint their love and their fantasies on the walls of the world” (and have a website of their own at ellaptr.com to prove it, so you can sample the results), have inspired another couple—Romand herself (image) and Jean-Jacques Birgé (sound)—to perform a comparable amount of serious play in the course of bringing them to our attention. Romand’s website offers a sample clip, as well as a link to a book with the same title (by the original couple) that I haven’t seen.

***

Another multilingual DVD—this one in spoken French, English, and Italian (with Italian, German, and English subtitles, and a 32-page booklet in all four languages) on PAL, from the Cineteca Bologna—is Mariann Lewinsky and Antonio Bigini’s Ella Maillart: Double Journey, a film I was lucky to discover at the Silent Film Festival held in Istanbul last December. Maillart (1903-1997), born in Geneva, was a remarkable and highly independent woman: a sailor in the 1924 Olympics, a world-champion skier in the early ’30s, a global traveller-writer-adventurer whose best friend was Delphine Seyrig’s mother, and, most relevant here, a remarkable photographer and occasional filmmaker. Assembled from diary entries, letters to Maillart’s mother, black-and-white still photographs, and film footage in both black and white and colour, Double Journey records Maillart’s travels through the Middle East from June 1939 to November 1940, undertaken with her friend Annemarie Schwarzenbach (who dropped out early in Kabul due to drug problems and a crush on an archaeologist).

Although the 40-minute film clearly benefits from a lovely and discrete soundtrack that includes Irène Jacob reciting the original French texts, what really packs a wallop is Maillart’s still photography and film footage, and not only because of the interest of what she was recording (which includes many spectacular landscapes as well as people, animals, and buildings in Turkey, Afghanistan, Iran, and India). A completed silent film by Maillart that is almost as long, Nomades afghans, is included as an extra, accompanied by her own commentary about it before a Lausanne audience in 1992, and the other extras include silent footage of her taken by Jean Grémillon (with whom she had a brief affair) in 1926, and two alternate versions of Double Journey in which the Maillart texts are recited in Italian (by filmmaker Alina Marazzi) and English (by performer Kate McIntosh). What emerges from all this is not only a multilayered history lesson, but also a feast for the senses.

***

Curiously enough, the same thing could be said for Hawaii. I never thought of seeing George Roy Hill’s 1966 movie version of James A. Michener’s mammoth novel until Twilight Time thoughtfully brought it to my attention, on a Blu-ray that includes both the 161-minute release (in high definition) and the 189-minute roadshow version (in standard definition). I watched the former of these, and even if I was bored by some of the obligatory action sequences, I was surprised at how edgy it was for a generic Hollywood blockbuster in charting the annihilation of Hawaiian native culture (including its peaceful spirituality as well as its incest) brought by Christianity and capitalism during the 19th century, and by making an intolerant and often repulsive Calvinist missionary (Max von Sydow) its central figure. I was also pleased to discover that Pauline Kael, in her two pages devoted to the film in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, was fully attuned to the movie’s special merits. As she concluded, and I concur, “this movie sticks to your bones.”

***

My favourable memory of Burt Reynolds’ The End (1978)—an unlikely and unabashedly vulgar but often hilarious slapstick farce, scripted by Jerry Belson, about a businessman (Reynolds) discovering from his doctor that he has at most a year to live, and who spends most of the remainder of the movie half-heartedly trying to commit suicide—led me to take another look at it on the Olive Films Blu-ray, and was happy to learn that it holds up, at least for me. The only times it reverts to squishy sentiments involve the hero’s young daughter (Kristy McNichol), and these are mercifully brief; the remainder is sustained by an interesting oddball cast (Sally Field as Reynolds’ mistress, Joanne Woodward as his ex, Dom DeLuise in a manic turn as a certified maniac, and cameos by Norman Fell, Myrna Loy, Pat O’Brien, Robby Benson, and Rob Reiner) and Reynolds’ brave willingness to make himself look as unheroic and ridiculous as possible.

Jonathan Rosenbaum- « Previous

- 1

- 2