Global Discoveries on DVD: Missing Directors, Extras, First Looks

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Missing Directors

1. I’m one of those people who habitually confuses Daniel Mann (1912-1991) with Delbert Mann (1920-2007) and vice versa, and I suspect that part of my confusion is both historical and generational: neither director receives an entry in Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema, and considerations of both tend to get ground underfoot by the reflexes of the mise en scène criticism that flourished under its banner, which excluded televisual mise en scène (Delbert Mann’s specialty, after his hopes for a career directing theatre failed to pan out) and theatre directing as a matter of course. Both directors started out as stage actors, and Daniel Mann, unlike Delbert, had some experience as a Broadway director before he went to Hollywood; his own TV work came later.

Daniel Mann, born Daniel Chugerman, directed, among much else, Come Back, Little Sheba (1952), I’ll Cry Tomorrow (1955), The Rose Tattoo (1955), The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), Butterfield 8 (1960), Our Man Flint (1966), and Playing for Time (1980); Delbert Mann directed, among much else, a lot of TV dramas and made-for-TV movies, Marty (1955), The Bachelor Party (1957), Separate Tables (1958), Middle of the Night (1959), The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1960), Lover Come Back (1961), and That Touch of Mink (1962).

As can be seen from the above, very selective lists, both Manns tended to be associated with playwrights: both with William Inge, Daniel with Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, Delbert with Paddy Chayefsky and Terrence Rattigan. Both might be associated with what might be termed the Hal Wallis Policy of Cultural Privilege in the ’50s and early ’60s, when Oscars were routinely handed out to adaptations of Broadway plays (most typically those about sad creatures suffering through the disillusions of middle age) and vehicles for Jerry Lewis and Elvis Presley were routinely aimed at kids and teenagers. (I can’t help but suspect that Lewis titling one of his early home-movie productions Come Back, Little Shiksa was partly motivated by this policy, which effectively destroyed his stateside artistic credentials in mainstream culture.)

My recent looks at the Paramount DVDs of Daniel Mann’s Come Back, Little Sheba and George Seaton’s The Country Girl (1954) and the Kino Lorber Blu-ray of Delbert Mann’s Separate Tables, combined with earlier looks at Marty, Middle of the Night, and Playing for Time (whose Olive Blu-ray I wrote about in my Winter 2014 column), among others, were motivated by a desire to re-evaluate the sort of fare that my parents tended to take more seriously than I did at the time of their first releases. (Reseeing The Country Girl, based on the Clifford Odets play, was specifically prompted by my viewing of Robert Trachtenberg’s excellent PBS American Masters documentary Bing Crosby Rediscovered, also available on DVD.) It proved to be time well spent—and redeemed, most of all, by the performances, including in most cases the ones that got Oscars or Oscar nominations: Shirley Booth and Burt Lancaster in Come Back, Little Sheba, Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly (as well as William Holden) in The Country Girl, and David Niven, Wendy Hiller, Deborah Kerr, and Burt Lancaster (as well as Rita Hayworth) in Separate Tables. Like the Oscar-winning contributions of director Franklin J. Schaffner, screenwriter Francis Ford Coppola, and actor George C. Scott on Patton (1970)—available in an excellent two-disc edition from 20th Century Fox’s Cinema Classics—these performances prove that at least some of the Oscars won in years past were genuinely earned.

My recent looks at the Paramount DVDs of Daniel Mann’s Come Back, Little Sheba and George Seaton’s The Country Girl (1954) and the Kino Lorber Blu-ray of Delbert Mann’s Separate Tables, combined with earlier looks at Marty, Middle of the Night, and Playing for Time (whose Olive Blu-ray I wrote about in my Winter 2014 column), among others, were motivated by a desire to re-evaluate the sort of fare that my parents tended to take more seriously than I did at the time of their first releases. (Reseeing The Country Girl, based on the Clifford Odets play, was specifically prompted by my viewing of Robert Trachtenberg’s excellent PBS American Masters documentary Bing Crosby Rediscovered, also available on DVD.) It proved to be time well spent—and redeemed, most of all, by the performances, including in most cases the ones that got Oscars or Oscar nominations: Shirley Booth and Burt Lancaster in Come Back, Little Sheba, Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly (as well as William Holden) in The Country Girl, and David Niven, Wendy Hiller, Deborah Kerr, and Burt Lancaster (as well as Rita Hayworth) in Separate Tables. Like the Oscar-winning contributions of director Franklin J. Schaffner, screenwriter Francis Ford Coppola, and actor George C. Scott on Patton (1970)—available in an excellent two-disc edition from 20th Century Fox’s Cinema Classics—these performances prove that at least some of the Oscars won in years past were genuinely earned.

I should add that two of the four performances that impressed me the most came from the actors I least expected to be moved by: Shirley Booth and David Niven. (The third, Deborah Kerr, had already raised my expectations through a recent reseeing of The Innocents—see below—and my recollections of Hiller in I Know Where I’m Going! [1945] already led me to expect a lot from her.) It’s harder to evaluate Lancaster, Crosby, Kelly, and Hayworth, as good as they are, because they all share with Niven the burden as well as the opportunity of “trick” casting by playing against their usual typecasting, which may make one unduly grateful for the expanded sense of their abilities that arises from this.

There are no extras on the Paramount DVDs, but Delbert Mann has a fascinating audio commentary on the Blu-ray of Separate Tables that has a lot to say about the studio sending him to Bournemouth during pre-production, Henry Horner’s set construction and the difficulties this led to in lighting, and the recutting and re-scoring (with David Raksin’s reluctant compliance) that took place after Mann was taken off the picture during post-production. (When Mann discovered, after the film’s premiere, that a schmaltzy theme song vocalized by Vic Damone had been added behind the credits, he immediately ended his association with the film’s production company Hecht-Hill-Lancaster.) He even records his protracted efforts to get Lancaster to dispense with a dynamic hand-into-fist gesture that conformed with his Hollywood persona but not with the character he was playing, and his regret that the studio retained an alternate take where the gesture remained rather than the one he chose.

There are no extras on the Paramount DVDs, but Delbert Mann has a fascinating audio commentary on the Blu-ray of Separate Tables that has a lot to say about the studio sending him to Bournemouth during pre-production, Henry Horner’s set construction and the difficulties this led to in lighting, and the recutting and re-scoring (with David Raksin’s reluctant compliance) that took place after Mann was taken off the picture during post-production. (When Mann discovered, after the film’s premiere, that a schmaltzy theme song vocalized by Vic Damone had been added behind the credits, he immediately ended his association with the film’s production company Hecht-Hill-Lancaster.) He even records his protracted efforts to get Lancaster to dispense with a dynamic hand-into-fist gesture that conformed with his Hollywood persona but not with the character he was playing, and his regret that the studio retained an alternate take where the gesture remained rather than the one he chose.

2. John Frankenheimer is another casualty of auteur criticism, which tended to rule out his remarkable work in live television (one could even argue that he did for that short-lived medium something comparable to what Welles did for radio) and the enduring impact this had on his seven black-and-white features, the three best of which are The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seven Days in May (1964), and Seconds (1966). I don’t like either Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) or The Train (1964)—two welcome recent releases from Twilight Time, both starring Burt Lancaster—as much as these, although they certainly have their points, especially the former. (What I find missing from Julie Kirgo’s accompanying essay, with its gratifying defense of Frankenheimer, is the most notable fact about Birdman’s real-life subject Robert Stroud, which the film also omits: that he was an aggressive homosexual, something which I had to find out from Wikipedia.)

2. John Frankenheimer is another casualty of auteur criticism, which tended to rule out his remarkable work in live television (one could even argue that he did for that short-lived medium something comparable to what Welles did for radio) and the enduring impact this had on his seven black-and-white features, the three best of which are The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seven Days in May (1964), and Seconds (1966). I don’t like either Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) or The Train (1964)—two welcome recent releases from Twilight Time, both starring Burt Lancaster—as much as these, although they certainly have their points, especially the former. (What I find missing from Julie Kirgo’s accompanying essay, with its gratifying defense of Frankenheimer, is the most notable fact about Birdman’s real-life subject Robert Stroud, which the film also omits: that he was an aggressive homosexual, something which I had to find out from Wikipedia.)

3. To my taste, one of the smartest and most useful reviews Pauline Kael ever wrote was of Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961), which was included in her first collection I Lost It at the Movies but inexplicably omitted in both her swan-song compendium For Keeps and Sanford Schwartz’s The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael. Rereading Kael’s spot-on appreciation after belatedly looking at the BFI’s excellent DVD—which includes a fine, detailed introduction by Christopher Frayling and Clayton’s short 1955 Gogol adaptation The Bespoke Overcoat as extras (to which the more recently released Blu-ray appends another Clayton short, the 1944 WWII documentary Naples Is a Battlefield)—I liked the film and her piece about it every bit as much as I did over half a century earlier. In fact, having read much more of Henry James in the interim, I value it even more now as a discerning piece of literary criticism as well as a solid assessment of the film’s strengths (especially Deborah Kerr’s performance), so my only regret about the BFI package is that this review isn’t reprinted in the accompanying booklet. Even so, Frayling’s 25-minute introduction is such an exceptional model of how to combine critical insight with useful information that I can’t really complain.

3. To my taste, one of the smartest and most useful reviews Pauline Kael ever wrote was of Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961), which was included in her first collection I Lost It at the Movies but inexplicably omitted in both her swan-song compendium For Keeps and Sanford Schwartz’s The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael. Rereading Kael’s spot-on appreciation after belatedly looking at the BFI’s excellent DVD—which includes a fine, detailed introduction by Christopher Frayling and Clayton’s short 1955 Gogol adaptation The Bespoke Overcoat as extras (to which the more recently released Blu-ray appends another Clayton short, the 1944 WWII documentary Naples Is a Battlefield)—I liked the film and her piece about it every bit as much as I did over half a century earlier. In fact, having read much more of Henry James in the interim, I value it even more now as a discerning piece of literary criticism as well as a solid assessment of the film’s strengths (especially Deborah Kerr’s performance), so my only regret about the BFI package is that this review isn’t reprinted in the accompanying booklet. Even so, Frayling’s 25-minute introduction is such an exceptional model of how to combine critical insight with useful information that I can’t really complain.

4. Burn, Witch, Burn (1960), shot in black-and-white ’Scope, isn’t nearly as good as The Innocents or Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), but as a highly suggestive Freudian creepshow it clearly belongs in their company; as I remembered it fondly I ordered the DVD from MGM’s Limited Edition Collection, and found that much of it still holds up. The cast is mainly wooden (apart from Australian actress Margaret Johnston’s superb villainess) and I wouldn’t exactly describe director Sidney Hayers as “a subject for further research,” but the film’s jerky and occasionally awkward rhythms wind up serving the story rather well. And it’s really the script (by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont) and its even better source, Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife—a novel (not a “story,” as the movie’s credits have it) that first appeared in the wonderful fantasy pulp magazine Unknown Worlds in 1943, and which I was originally led to by a rave review in Damon Knight’s delightful essay collection In Search of Wonder—that deserves credit for most of what’s good here. If memory serves, the film is a reasonably faithful adaptation; though the setting has been shifted from a small-town American university and environs to somewhere comparable in the UK, most of the novel’s petty academic rivalries are more or less intact.

4. Burn, Witch, Burn (1960), shot in black-and-white ’Scope, isn’t nearly as good as The Innocents or Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), but as a highly suggestive Freudian creepshow it clearly belongs in their company; as I remembered it fondly I ordered the DVD from MGM’s Limited Edition Collection, and found that much of it still holds up. The cast is mainly wooden (apart from Australian actress Margaret Johnston’s superb villainess) and I wouldn’t exactly describe director Sidney Hayers as “a subject for further research,” but the film’s jerky and occasionally awkward rhythms wind up serving the story rather well. And it’s really the script (by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont) and its even better source, Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife—a novel (not a “story,” as the movie’s credits have it) that first appeared in the wonderful fantasy pulp magazine Unknown Worlds in 1943, and which I was originally led to by a rave review in Damon Knight’s delightful essay collection In Search of Wonder—that deserves credit for most of what’s good here. If memory serves, the film is a reasonably faithful adaptation; though the setting has been shifted from a small-town American university and environs to somewhere comparable in the UK, most of the novel’s petty academic rivalries are more or less intact.

5. Now that Pete Kelly’s Blues has finally become available on Blu-ray in the Warners Archive Collection, I hope I can be forgiven for adapting parts of an old blog post:

5. Now that Pete Kelly’s Blues has finally become available on Blu-ray in the Warners Archive Collection, I hope I can be forgiven for adapting parts of an old blog post:

“Jack Webb’s Pete Kelly’s Blues (1955) is a terrific, atmospheric, sometimes creepy period noir in CinemaScope and WarnerColor about a cornet player (Webb) in a Dixieland band in 1927 Kansas City (after an evocative prologue in 1915 New Orleans and 1919 Jersey City showing us where and how Pete Kelly came by his cornet). It’s got an amazing cast, most of them used flagrantly against type: Edmond O’Brien, Janet Leigh, Peggy Lee, Lee Marvin, Andy Devine (in a rare and very effective non-comic role), Ella Fitzgerald, and even a bit by Jayne Mansfield as a cigarette girl in a speakeasy. The screenplay, which deservedly gets star billing in the opening credits, is by Richard L. Breen, one-time president of the Screen Writers Guild and apparently a key writer on Webb’s Dragnet, and it’s full of wonderful and hilarious hard-boiled dialogue and off-screen narration by Webb. (When a flapper played by Leigh says to Kelly that April is her favourite month, he replies, ‘If you like it so much, I’ll buy it for you.’)…It seems that Webb was as passionate a jazz buff as Clint Eastwood, and this movie is at least as much of a labour of love as Bird. In his film Los Angeles Plays Itself, Thom Andersen compares Webb’s minimalist direction of Dragnet episodes to the direction of Ozu, but here the mise en scène is positively baroque in spots—and beautifully composed.”

Two of the more notable extras on the Blu-ray are an index that allows you to go straight to the songs and a couple of offbeat trailers for the film, both hosted by a weirdly affable Webb.

***

Extras

1. Regrettably, the same courtesy of indexing musical numbers isn’t done on Milestone’s Blu-ray of Shirley Clarke’s 1961 The Connection (whose numbers are much more worth accessing than those in Pete Kelly’s Blues, apart from Ella Fitzgerald’s performances) except incidentally, under different chapter titles (see #3 and #12). But otherwise, this edition offers a lot of contextual extras, ranging from interviews with pianist Freddie Redd (by Immy Humes) and art director Albert Bremmer (by Ross Lipman, whose restoration of The Connection is used on the disc) to Clarke’s home movies and production stills to two truly awful rock numbers contrived to promote the film. (The jacket alludes to a half-hour 1959 radio interview with Clarke that was left off the disc—a poorly recorded chat with Studs Terkel that predates The Connection—but Milestone’s Dennis Doros informs me that this interview can be accessed for free at https://vimeo.com/user4412172/review/117933886/b68afdb752.) Regrettably, Bremmer remembers practically nothing about The Connection, and Redd only gets around to playing the piano he’s sitting beside when he’s prodded in the closing minutes of his interview, but by way of compensation, we hear much more of his soloing over the silent home movies and production stills.

1. Regrettably, the same courtesy of indexing musical numbers isn’t done on Milestone’s Blu-ray of Shirley Clarke’s 1961 The Connection (whose numbers are much more worth accessing than those in Pete Kelly’s Blues, apart from Ella Fitzgerald’s performances) except incidentally, under different chapter titles (see #3 and #12). But otherwise, this edition offers a lot of contextual extras, ranging from interviews with pianist Freddie Redd (by Immy Humes) and art director Albert Bremmer (by Ross Lipman, whose restoration of The Connection is used on the disc) to Clarke’s home movies and production stills to two truly awful rock numbers contrived to promote the film. (The jacket alludes to a half-hour 1959 radio interview with Clarke that was left off the disc—a poorly recorded chat with Studs Terkel that predates The Connection—but Milestone’s Dennis Doros informs me that this interview can be accessed for free at https://vimeo.com/user4412172/review/117933886/b68afdb752.) Regrettably, Bremmer remembers practically nothing about The Connection, and Redd only gets around to playing the piano he’s sitting beside when he’s prodded in the closing minutes of his interview, but by way of compensation, we hear much more of his soloing over the silent home movies and production stills.

The Connection remains my favourite Clarke film, even though it may also be the most dated (apart from the wonderful music), because it remains my key memento of three of the best nights I ever spent in a theatre, during the play’s initial run. It was so quintessentially theatrical as well as confrontational that no film could approximate it—which is why the film remains so theatrical (in an unfortunate way) in spite of all of Clarke’s ingenuity in adapting it. In many respects, the true auteur of the original work was the Living Theater’s Judith Malina (even more than playwright Jack Gelber), and it’s an unavoidable pity that her stamp gets lost in the transfer, and that Jonas Mekas subsequently wound up filming her equally adroit but less corrosive work on The Brig instead of The Connection.

2. I enjoyed re-seeing François Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black (1968) on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray, but I can’t really say I enjoyed hearing Bernard Herrmann grouch and yell at his interviewers from the Los Angeles Free Press in the accompanying 79-minute CD, Conversation Piece: An Unvarnished Chat with Bernard Herrmann (1970), and I didn’t even try to watch the film’s English-dubbed version, which is also included (presumably in part because it includes some variants in the Herrmann score). Even so, this is a package well worth having, especially for the audio commentary by Julie Kirgo, Nick Redman, and Herrmann expert Stephen C. Smith—the latter of whom reveals a great deal about how much Truffaut tampered with the music, and all of whom speculate intelligently on why this happened (as well as on why Truffaut fought with cinematographer Raoul Coutard about the employments of colour).

2. I enjoyed re-seeing François Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black (1968) on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray, but I can’t really say I enjoyed hearing Bernard Herrmann grouch and yell at his interviewers from the Los Angeles Free Press in the accompanying 79-minute CD, Conversation Piece: An Unvarnished Chat with Bernard Herrmann (1970), and I didn’t even try to watch the film’s English-dubbed version, which is also included (presumably in part because it includes some variants in the Herrmann score). Even so, this is a package well worth having, especially for the audio commentary by Julie Kirgo, Nick Redman, and Herrmann expert Stephen C. Smith—the latter of whom reveals a great deal about how much Truffaut tampered with the music, and all of whom speculate intelligently on why this happened (as well as on why Truffaut fought with cinematographer Raoul Coutard about the employments of colour).

Upon reflection, what may have stymied the film, at least in Truffaut’s eyes (and ears), was his effort to cross Hitchcock with Renoir—in principle, a theoretical and dialectical genre mix somewhat akin to Godard’s effort to make a “neorealist musical” in Une femme est une femme (1961). Unlike the genre mixes that characterized many other New Wave features, such as Shoot the Piano Player (1960) and Band of Outsiders (1964), this one yields something closer to a stalemate than a fruitful collision of elements, albeit one with many redeeming moments. (Kirgo is especially good at perceiving the film as a kind of autocritique by Truffaut on his objectification of women.)

3. I’m not sure why, but the only way you can get John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) on Blu-ray is to order it from France (from French Amazon, it cost me 9,89 euros plus postage), even though it comes with American extras: an excellent audio commentary by F.X. Feeney (who’s clearly been thinking about this movie for most of his life) and a documentary called Monument Valley: John Ford Country. I continue to find it Ford’s most troubling film; even though Jean-Marie Straub has rightly described it as Ford at his most Brechtian, it’s hard to shake loose Feeney’s admission that, as a kid, he identified most closely with Henry Fonda’s myopic and monstrously racist Col. Thursday. I’m sure Feeney wasn’t alone in this: the movie was a huge success on its release, and figuring out what it was actually saying and doing politically in 1948 is for me just as slippery as trying to square the Brechtian subtexts of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959) with the reactionary applause that film was garnering from my fellow Alabamans over a decade later. (Ford’s 1952 The Quiet Man, which I recently resaw on the beautiful Olive Blu-ray, is similarly split: a pacifist Irish fantasy culminating in a joyous, audience-pleasing fistfight that brings together and reconciles an entire argumentative community.) Even so, the late Gilberto Perez’s discussion of Fort Apache in The Material Ghost comes closer for me than any other in describing the coherence of the film’s incoherence, morally as well as politically. (Trying to figure out what John Wayne thought about the film’s meaning is a genuine stumper.)

3. I’m not sure why, but the only way you can get John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) on Blu-ray is to order it from France (from French Amazon, it cost me 9,89 euros plus postage), even though it comes with American extras: an excellent audio commentary by F.X. Feeney (who’s clearly been thinking about this movie for most of his life) and a documentary called Monument Valley: John Ford Country. I continue to find it Ford’s most troubling film; even though Jean-Marie Straub has rightly described it as Ford at his most Brechtian, it’s hard to shake loose Feeney’s admission that, as a kid, he identified most closely with Henry Fonda’s myopic and monstrously racist Col. Thursday. I’m sure Feeney wasn’t alone in this: the movie was a huge success on its release, and figuring out what it was actually saying and doing politically in 1948 is for me just as slippery as trying to square the Brechtian subtexts of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959) with the reactionary applause that film was garnering from my fellow Alabamans over a decade later. (Ford’s 1952 The Quiet Man, which I recently resaw on the beautiful Olive Blu-ray, is similarly split: a pacifist Irish fantasy culminating in a joyous, audience-pleasing fistfight that brings together and reconciles an entire argumentative community.) Even so, the late Gilberto Perez’s discussion of Fort Apache in The Material Ghost comes closer for me than any other in describing the coherence of the film’s incoherence, morally as well as politically. (Trying to figure out what John Wayne thought about the film’s meaning is a genuine stumper.)

4. My three favourite late Billy Wilder films—The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), Avanti! (1972), and Fedora (1978)—are all available now on Blu-ray, although the second of these (which I persist in finding the best, although it remains the least known) is again only available from France. The first, from Kino Lorber, comes with a slew of extras—many of them devoted to giving us rough ideas of all the missing episodes from Wilder’s intended three-hour version of the film—but for all its continuing charms, the film enchanted me less this time around, if only because the shtick of using Watson’s (Colin Blakely) sputtering incomprehension as a comic form of exposition grows tiresome with mechanical repetition. Fedora, on the other hand (which comes from Olive and therefore has no extras at all), in spite of its more abrasive elements, enchanted me more than it had previously, thanks to Dave Kehr’s excellent essay about the film in his book When Movies Mattered (which largely focuses on what makes it abrasive). But the Avanti! Blu-ray, which comes with a couple of talking-head extras in unsubtitled French, is undoubtedly the treasure in the bunch, not least because it includes an entire second Wilder feature on a separate disc (an “extra” that wasn’t even mentioned in the French Amazon listing): the 1964 Kiss Me, Stupid, which, like Avanti!, is one of Wilder’s best and most neglected features (perhaps because it’s equally anti-American).

4. My three favourite late Billy Wilder films—The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), Avanti! (1972), and Fedora (1978)—are all available now on Blu-ray, although the second of these (which I persist in finding the best, although it remains the least known) is again only available from France. The first, from Kino Lorber, comes with a slew of extras—many of them devoted to giving us rough ideas of all the missing episodes from Wilder’s intended three-hour version of the film—but for all its continuing charms, the film enchanted me less this time around, if only because the shtick of using Watson’s (Colin Blakely) sputtering incomprehension as a comic form of exposition grows tiresome with mechanical repetition. Fedora, on the other hand (which comes from Olive and therefore has no extras at all), in spite of its more abrasive elements, enchanted me more than it had previously, thanks to Dave Kehr’s excellent essay about the film in his book When Movies Mattered (which largely focuses on what makes it abrasive). But the Avanti! Blu-ray, which comes with a couple of talking-head extras in unsubtitled French, is undoubtedly the treasure in the bunch, not least because it includes an entire second Wilder feature on a separate disc (an “extra” that wasn’t even mentioned in the French Amazon listing): the 1964 Kiss Me, Stupid, which, like Avanti!, is one of Wilder’s best and most neglected features (perhaps because it’s equally anti-American).

5. Three other recent packages from France should be noted:

a) I haven’t yet found the time to properly explore Panfilov/Tchourikova, an attractively packaged four-disc DVD set from potemkine.fr, except to note that it includes four features by Gleb Panfiilov and his wife and lead actress Inna Tchourikova, all with French subtitles and filmed introductions in French: Pas de gué dans le feu (1967), Le Début (1970), Je demande la parole (1975), and La Thème (1979).

b) Carlotta’s pairing of Orson Welles’ two versions of Macbeth (1948 and 1950) with the “official 1993 restoration” (both the first and last word, alas, fully deserve the quotation marks) of his 1952 Othello, all three on Blu-rays with many extras, and a French-language DVD of Isidro Romero’s 53-minute Shakespeare et Orson Welles (1975). The Blu-ray extras include a lengthy commentary in English by Joseph McBride; newsreel footage of the end of Welles’ 1936 “Voodoo” Macbeth on stage; the full 1940 audio version of Macbeth recorded for Mercury Text Records; Hilton Edwards’ 1951 short Return to Glennascaul; and many more features in untranslated French, including commentaries by Welles experts François Thomas and Jean-Pierre Berthomé. The only sticking point here is that neither of the Welles-edited versions of Othello (with his own original soundtracks) is included, because the “official” copyright holders have effectively outlawed these versions. (Whoever said that Anglo-American “free speech” doesn’t entail capitalist censorship?) But at least McBride, in his commentary, does a pretty good job of detailing some of the losses and absences involved.

b) Carlotta’s pairing of Orson Welles’ two versions of Macbeth (1948 and 1950) with the “official 1993 restoration” (both the first and last word, alas, fully deserve the quotation marks) of his 1952 Othello, all three on Blu-rays with many extras, and a French-language DVD of Isidro Romero’s 53-minute Shakespeare et Orson Welles (1975). The Blu-ray extras include a lengthy commentary in English by Joseph McBride; newsreel footage of the end of Welles’ 1936 “Voodoo” Macbeth on stage; the full 1940 audio version of Macbeth recorded for Mercury Text Records; Hilton Edwards’ 1951 short Return to Glennascaul; and many more features in untranslated French, including commentaries by Welles experts François Thomas and Jean-Pierre Berthomé. The only sticking point here is that neither of the Welles-edited versions of Othello (with his own original soundtracks) is included, because the “official” copyright holders have effectively outlawed these versions. (Whoever said that Anglo-American “free speech” doesn’t entail capitalist censorship?) But at least McBride, in his commentary, does a pretty good job of detailing some of the losses and absences involved.

c) The only Blu-ray version of Jacques Tourneur’s final masterpiece, Night of the Demon (1957)—probably my favourite horror film of the ’50s—can now be had on Wild Side’s precious dual-format box set Rendez-vous avec la peur, where it’s coupled with the shortened American version (Curse of the Demon) and a beautifully illustrated 144-page book by Michael Henry Wilson, Le versant crépusculaire, which is comparable in many respects to Tony Earnshaw’s 2005 book on the same subject, Beating the Devil: The Making of Night of the Demon. I haven’t yet found time to properly compare these two books, except to notice that Cy Endfield’s unheralded contributions to this film are dealt with in both—reminding me of my embarrassed silence when Endfield told me in 1993 that he thought he could have done a better job than Tourneur in directing the picture. (I should further note that Wild Side’s many book-and-film combos devoted to Hollywood treasures continue to be a major resource.)

c) The only Blu-ray version of Jacques Tourneur’s final masterpiece, Night of the Demon (1957)—probably my favourite horror film of the ’50s—can now be had on Wild Side’s precious dual-format box set Rendez-vous avec la peur, where it’s coupled with the shortened American version (Curse of the Demon) and a beautifully illustrated 144-page book by Michael Henry Wilson, Le versant crépusculaire, which is comparable in many respects to Tony Earnshaw’s 2005 book on the same subject, Beating the Devil: The Making of Night of the Demon. I haven’t yet found time to properly compare these two books, except to notice that Cy Endfield’s unheralded contributions to this film are dealt with in both—reminding me of my embarrassed silence when Endfield told me in 1993 that he thought he could have done a better job than Tourneur in directing the picture. (I should further note that Wild Side’s many book-and-film combos devoted to Hollywood treasures continue to be a major resource.)

6. The numerous extras on Criterion’s double bill of Monte Hellman’s legendary 1966 westerns The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind—including multiple interviews with Hellman and many of his surviving collaborators, an audio commentary by Hellman with Bill Krohn and Blake Lucas, and a video tribute to Warren Oates by Kim Morgan—answers most of the questions anyone could have about these bizarre rough gems, except for the main one that keeps nagging me every time I see The Shooting (which involves a spoiler): namely, how and why the Millie Perkins character manages to hire the Warren Oates character to track down his twin brother without once alluding to the fact that he is, in fact, his twin brother. (Making sense out of most of the absurdist plots of Hellman’s films is probably a fool’s game anyway, especially if one heads straight for the metaphysics and ignores all the plot plausibility issues, as most commentators do.) Raro Video’s new and remastered HD transfer of Hellman’s 1988 Iguana has its share of helpful appendages as well, and, more importantly, manages to restore a couple of minutes that were accidentally omitted from the last release of Hellman’s cut.

6. The numerous extras on Criterion’s double bill of Monte Hellman’s legendary 1966 westerns The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind—including multiple interviews with Hellman and many of his surviving collaborators, an audio commentary by Hellman with Bill Krohn and Blake Lucas, and a video tribute to Warren Oates by Kim Morgan—answers most of the questions anyone could have about these bizarre rough gems, except for the main one that keeps nagging me every time I see The Shooting (which involves a spoiler): namely, how and why the Millie Perkins character manages to hire the Warren Oates character to track down his twin brother without once alluding to the fact that he is, in fact, his twin brother. (Making sense out of most of the absurdist plots of Hellman’s films is probably a fool’s game anyway, especially if one heads straight for the metaphysics and ignores all the plot plausibility issues, as most commentators do.) Raro Video’s new and remastered HD transfer of Hellman’s 1988 Iguana has its share of helpful appendages as well, and, more importantly, manages to restore a couple of minutes that were accidentally omitted from the last release of Hellman’s cut.

7. Even more generous in terms of extras is Criterion’s fabulous Blu-ray of Guy Maddin’s My Winnipeg (2007), which comes equipped with no less than five recent Maddin shorts, four brand new “cine-essays” he co-authored with Evan Johnson on Winnipegian subjects, a 2008 “making-of” featurette, and a lengthy conversation between Maddin and art critic Robert Enright.

8. Finally, two exceptionally eye-opening audiovisual pieces of film criticism: Kevin Lee’s Viewing Between the Lines, included on Cinema Guild’s DVD of Hong Sangsoo’s 2011 The Day He Arrives (a curious feature I was tardy in catching up with), and : : kogonada’s visual essay on the 2014 Criterion Blu-ray of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960). The printed essays accompanying these releases (by James Quandt and Gary Giddins, respectively) are both worth reading, but these two extras taught me a lot more.

First Looks

1. My belated introduction to the great Kinoshita Keisuke (1912-1998) came about courtesy of the latest Eclipse package from Criterion, Kinoshita and World War II,

1. My belated introduction to the great Kinoshita Keisuke (1912-1998) came about courtesy of the latest Eclipse package from Criterion, Kinoshita and World War II,

comprising his first five features. I started off with the last two of these, Army (1944) and Morning for the Osone Family (1946)—both propaganda films (made during and after the war), both centring on families surviving (or not) and adjusting (or not) through the ravages of war—and they proved to be a very interesting pair and a rewarding double feature, for their continuities as well as their discontinuities. I have to admit I prefer the first of these (starring two of my favourite Japanese actors, Tanaka Kinuyo and Ryu Chishu) even though it qualifies, according to Sato Tadao, as “fascist in content” in spite of “its sentimental emphasis on the soldier’s mother [Tanaka],” as evinced in the film’s dialogue-less closing sequence. But what’s most remarkable about the neutrally titled Army (apart from its masterfully bustling mise en scène) is precisely how this wrenching, protracted, and unmistakably pacifist final sequence subverts everything preceding it even more than the ending of Ford’s Fort Apache does or did, and with far more radical consequences (Kinoshita was accused of treason by an army general after the film’s premiere). Conversely, the propagandistically titled Morning for the Osone Family appears to suffer far more from government interference (the US Occupation, in this case) than its wartime predecessor. Even though Kinoshita clearly subscribed (as I do) to the film’s antiwar message, that message is conveyed in a hectoring tone that grows progressively shriller and reaches its nadir in an imposed happy ending that Kinoshita was obliged to add (as I learned from Audie Bock’s Japanese Film Directors), breaking away from the film’s central one-house set in a manner that undermines (rather than subverts) everything preceding it with its bogus uplift.

As grateful as I am for this set, I have to lodge a complaint about the packaging: why does Criterion persist in making Michael Koresky’s useful notes to each film in its Eclipse releases almost completely illegible? The white letters against a light beige background in this case aren’t even attractive, much less functional, and it’s hard to understand the motivation behind such graphic obstruction.

2. Watching the serviceable if humdrum documentary about Frank Capra included on the Criterion Blu-ray of It Happened One Night (1934), I realized that I’d never seen Capra’s State of the Union (1948), so I ordered the no-frills Universal DVD of that film. In a concise fashion, the three successive opening studio logos—Universal’s (in colour), MGM’s on the soundtrack only (the roar of Leo the Lion heard over black leader), and finally Liberty Films’ (in black and white)—prepared me for all the political and existential confusions and contradictions that followed. This ideological mess culminates in the final (and in some respects best) sequence, where Spencer Tracy’s Republican presidential candidate suddenly confesses to the public that he’s a liar and a traitor to his own beliefs and that he’s dropping out of politics, although he plans to attend both the Republican and Democratic conventions anyway to voice his beliefs, which automatically makes him both a populist hero and a winner. It’s a bit like the conclusion of Preston Sturges’ Hail the Conquering Hero (1944), but without the despairing irony behind the uplift, which makes the whole scene pointless. But at least the slew of character actors clogging up the scenery, as in Sturges, is loads of fun.

2. Watching the serviceable if humdrum documentary about Frank Capra included on the Criterion Blu-ray of It Happened One Night (1934), I realized that I’d never seen Capra’s State of the Union (1948), so I ordered the no-frills Universal DVD of that film. In a concise fashion, the three successive opening studio logos—Universal’s (in colour), MGM’s on the soundtrack only (the roar of Leo the Lion heard over black leader), and finally Liberty Films’ (in black and white)—prepared me for all the political and existential confusions and contradictions that followed. This ideological mess culminates in the final (and in some respects best) sequence, where Spencer Tracy’s Republican presidential candidate suddenly confesses to the public that he’s a liar and a traitor to his own beliefs and that he’s dropping out of politics, although he plans to attend both the Republican and Democratic conventions anyway to voice his beliefs, which automatically makes him both a populist hero and a winner. It’s a bit like the conclusion of Preston Sturges’ Hail the Conquering Hero (1944), but without the despairing irony behind the uplift, which makes the whole scene pointless. But at least the slew of character actors clogging up the scenery, as in Sturges, is loads of fun.

3. Jules Dassin’s Uptight (1968), his first post-blacklist American film, offered on an Olive Films Blu-ray, proved to be a genuine revelation. In retrospect, I must have avoided this because the whole notion of a Black Power remake of John Ford’s The Informer (1935) sounded like a bad idea, but the movie proved me wrong, emerging 40-odd years later not only as a valuable time capsule but as a creditable achievement in its own right. Even if it’s stagey in spots, Boris Kaufman’s colour cinematography (assisted in no small measure by Alexandre Trauner’s production design) and the lead performance by the unjustly forgotten Julian Mayfield (a novelist and activist who collaborated with Dassin and co-star Ruby Dee on the powerful screenplay)—not to mention a final sequence that clearly harks back to Dassin’s The Naked City (1948)—all make this an exciting and vibrant work.

3. Jules Dassin’s Uptight (1968), his first post-blacklist American film, offered on an Olive Films Blu-ray, proved to be a genuine revelation. In retrospect, I must have avoided this because the whole notion of a Black Power remake of John Ford’s The Informer (1935) sounded like a bad idea, but the movie proved me wrong, emerging 40-odd years later not only as a valuable time capsule but as a creditable achievement in its own right. Even if it’s stagey in spots, Boris Kaufman’s colour cinematography (assisted in no small measure by Alexandre Trauner’s production design) and the lead performance by the unjustly forgotten Julian Mayfield (a novelist and activist who collaborated with Dassin and co-star Ruby Dee on the powerful screenplay)—not to mention a final sequence that clearly harks back to Dassin’s The Naked City (1948)—all make this an exciting and vibrant work.

4. Susan L. Mizruchi’s interesting if uneven Brando’s Smile: His Life, Thought, and Work finally convinced me to see both the 1935 and 1962 versions of Mutiny on the Bounty, for the first time, on a Warners DVD and Blu-ray respectively. (I decided to skip the 1984 version, The Bounty.) And I blush to admit that the final (2015) volume of Leonard Maltin’s annual Movie Guide, which assigns four stars to the Frank Lloyd Oscar winner and only two and a half to the Lewis Milestone blunderbuss, proves to be more reliable in its judgment than Mizruchi’s book, even if the latter furnishes some interesting information about Brando’s influence over the 1962 version (including the fact that he directed his own death scene after the film’s original director Carol Reed had been fired and Milestone, his successor, had left the project in disgust). Many of Brando’s demanded script changes—such as emphasizing the class differences between Bligh and Christian and focusing on the mutineers’ experiences on Pitcairn Island—sound intelligent, but only the first of these really pays off in the final film. The awkward (if pointed) prologue and epilogue set on Pitcairn 30 years after the main events—bracketing the whole story with a moral that seems closely related to Sternberg’s The Saga of Anatahan (1953)—was removed after the film’s road-show release, and is included on the Blu-ray as two of the many extras. Yet it can’t make up for the crucial historical omission in both versions of the story, that all but three of the 18 Tahitian women originally taken to the island by the mutineers were kidnapped—another fact I gleaned from Wikipedia, but not from any bonus feature.

Paradoxically, the Clark Gable and Charles Laughton version wound up being more progressive than its ponderous successor in many respects, both in its depiction of Tahitian culture and in its unabashed eroticism. Maybe Gable “hadn’t even bothered to speak with an English accent,” as Brando complained to an interviewer, but he’s still Gable (and hardly “bland,” as Mizruchi charges); and even if Trevor Howard’s Bligh was scripted more thoughtfully than Laughton’s, Laughton still found ways of giving his Bligh plenty of humanity once he gets thrown off the ship. (It’s worth adding that the best extra on either disc is a blatantly racist but historically fascinating ’30s documentary, Pitcairn Island Today, on the DVD of the 1935 version.)

Paradoxically, the Clark Gable and Charles Laughton version wound up being more progressive than its ponderous successor in many respects, both in its depiction of Tahitian culture and in its unabashed eroticism. Maybe Gable “hadn’t even bothered to speak with an English accent,” as Brando complained to an interviewer, but he’s still Gable (and hardly “bland,” as Mizruchi charges); and even if Trevor Howard’s Bligh was scripted more thoughtfully than Laughton’s, Laughton still found ways of giving his Bligh plenty of humanity once he gets thrown off the ship. (It’s worth adding that the best extra on either disc is a blatantly racist but historically fascinating ’30s documentary, Pitcairn Island Today, on the DVD of the 1935 version.)

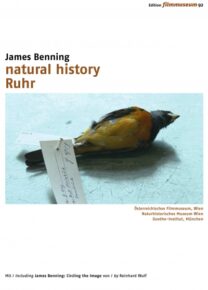

5. Like most of the people reading this, I’ve had a hell of a time keeping up with the burgeoning work of James Benning over the past few years, apart from lucky opportunities to see Twenty Cigarettes and Nightfall (both 2011); I’m especially curious about his “remakes” of Faces (1968) and Easy Rider (1969). So the fifth of the Edition Filmmuseum’s DVD double features devoted to Benning—highlighting his growing relationships with Germany and Austria and including both his first digital work, Ruhr (2009, 122 minutes, seven shots) and natural history (2014, 77 minutes), along with a 2009 Viennale trailer (Fire & Rain) and Reinhard Wulf’s 2003 documentary about Benning for German TV (which I’ve already seen)—is especially welcome. So far, I’ve only found time to watch the first half of Ruhr and read the first half of the 28-page bilingual booklet (with enlightening contributions by Alexander Horwath, Benning himself, and Werner Dütsch), which whets my appetite for more. And once I’m done with these, I’m looking forward to watching two more recent two-disc sets from this stupendous label: restored versions of Eisenstein’s Potemkin (1925) and October (1928) with their original accompanying scores by Edmund Meisel; and the earliest surviving versions of Dziga Vertov’s Three Songs of Lenin (the 1938 silent and sound reissues), along with two of Vertov’s Kinopravda newsreels related to Lenin and a feature-length Austrian documentary about Vertov by Peter Konlechner.

5. Like most of the people reading this, I’ve had a hell of a time keeping up with the burgeoning work of James Benning over the past few years, apart from lucky opportunities to see Twenty Cigarettes and Nightfall (both 2011); I’m especially curious about his “remakes” of Faces (1968) and Easy Rider (1969). So the fifth of the Edition Filmmuseum’s DVD double features devoted to Benning—highlighting his growing relationships with Germany and Austria and including both his first digital work, Ruhr (2009, 122 minutes, seven shots) and natural history (2014, 77 minutes), along with a 2009 Viennale trailer (Fire & Rain) and Reinhard Wulf’s 2003 documentary about Benning for German TV (which I’ve already seen)—is especially welcome. So far, I’ve only found time to watch the first half of Ruhr and read the first half of the 28-page bilingual booklet (with enlightening contributions by Alexander Horwath, Benning himself, and Werner Dütsch), which whets my appetite for more. And once I’m done with these, I’m looking forward to watching two more recent two-disc sets from this stupendous label: restored versions of Eisenstein’s Potemkin (1925) and October (1928) with their original accompanying scores by Edmund Meisel; and the earliest surviving versions of Dziga Vertov’s Three Songs of Lenin (the 1938 silent and sound reissues), along with two of Vertov’s Kinopravda newsreels related to Lenin and a feature-length Austrian documentary about Vertov by Peter Konlechner.

- « Previous

- 1

- 2