TIFF Preview -4: Rebelle | Room 237 | As If We Were Catching a Cobra | Beyond the Hills | Dust | It Was the Son | Jackie | Motorway | The Paperboy | The Perks of Being a Wallflower | Shores of Hope | The War of the Volcanoes

Cinema Scope 52 Preview

Rebelle (Kim Nguyen, Canada)—Special Presentation

By Kiva Reardon

The year in cinema has been stamped with a modicum of magical realism. First up at Sundance was Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, a film routinely described as “lyrical” and “heartwarming.” Now there is Montréal director Kim Nguyen’s Rebelle, arriving at fall festivals after bowing in Berlin and taking top honours in Tribeca. The films share similarities beyond critical buzz: both are shot from the perspective of young girls, use amateur actors, and mobilize contemporary tragedies (post-Katrina New Orleans and African child soldiers, respectively) to set their scenes. That said, merely placing Rebelle in such divisive company without further elaboration does the film a disservice. More accomplished than Zeitlin’s work (and with no sparklers), the choice to blend the issue of child soldiers with the supernatural is more than merely whimsical, though ultimately no less problematic.

Rebelle is set in an unnamed African nation (the shooting took place in the Congo) during a civil war. Komona (played by Rachel Mwanza, though the narration is read by Diane Uwamahoro) tells the story of her life to her unborn child in stilted voiceover. Her basic observations—“I had to learn to make the tears go in my eyes,” she flatly states—are meant to make the horrors of her life all the more tragic when contrasted with her naïveté. Similarly, Nguyen’s main strategy is to swing manically between the horrendous and the idyllic to create a sense of tonal dynamism. We meet Komona at age 12 when Great Tiger rebels take her from her village. She is forced to kill her parents. She is drugged, starved, and brainwashed. She is literally haunted by the ghosts of her victims. The plot points echo newspaper stories on the contemporary crisis of child soldiers, which, when combined with the shaky hand-held camera, suggest the film purposefully strives for a documentary feel in between its phantasmatic elements. Mid-way through the film, however, Komona and a fellow child solider, an albino called Magicien (Serge Kanyinda), run away and fall in love: cue the lyricism.

This section feels like a film within a film, clearly demarcated by over-scoring and complete with a marriage plot involving a quest for a white rooster. While this reeks of pulling a Benigni—after the insufferable example par excellence of making the inhuman palatable, Life Is Beautiful (1997)—Nguyen seems to negotiate this transformation with more nuance. Though the love-story interlude offers some reprieve from the graphic horrors, Nguyen works hard to remind us the war is never far away: the Butcher (Ralph Prosper) keeps an empty bucket next to him as he hacks at cow carcasses, ready to catch his vomit as he’s reminded of what machetes did to his family. While at times Komona’s narration drives this point too forcefully home, there are subtle audio cues which are far more unsettling, as the film’s soundscape attunes itself to Komona’s perspective. For instance, the heightened sound of a machete hitting a tree upsets the calm of Komona and Magicien’s village life, recalling the use of the tool as a weapon in their hands. Such choices render this amorous pause more complex than a traditional love-in-wartime tale. And yet, it is only to mediocre ends. The problem with Rebelle is that despite the human suffering, the stakes feel incredibly low. Komona is protected by her narration (she is literally the master of her story) and magic. Both social and supernatural in nature, this magic takes form in the way in which she is protected after being named the rebel leader’s “war witch,” being the sole survivor from her village. This shielded position of power, when combined with the apparitions (which in one crucial battle protect her), early on reassures the audience that she will live, overcome, etc. The neo-Western ending—a truck driving towards the horizon, suggesting our child heroine rides to a brighter future—only reaffirms such sentiments.

Moreover, what suggests Rebelle is having its fantasy cake and eating it too is the film’s aim of universality. Though the details of the narrative recall stories of child soldiers in the Sudan, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone (Nguyen has said in interviews the film is based on a story from Burma), the ambiguity suggests the desire to mobilize the issue towards a Triumph of the Human Spirit tale. As always, the risk in such a move is apolitical desensitization, the whitewashing of a tangible issue for the sake of a grand narrative. Indeed, this becomes most apparent in the figures of the ghosts that plague Komona. Played by actors covered in a gray paste, their interpretation is decidedly theatrical in execution (think Julie Taymor), but the imagery further borrows from the figures emerging from the dust on 9/11, or the baby in the firefighter’s arms after the Oklahoma City bombing. Materializing from the brush and climbing over dark rocky outcrops that contrast with the pallor of their skin, the ghosts are not only fantasy-cum-art house figures, but literally other worldly. Though meant to be the incarnations of people killed in a specific conflict, they suggest an idealized view of shared suffering—the notion that we are all haunted by global conflicts.

Indeed, the film opens itself to such a reading the moment Jean-Claude Van Damme’s face appears, via an onscreen citation of Universal Soldier: Regeneration (2009). Sandwiched between a scene of Magicien play-fighting karate style and the children relaxing while watching Van Damme in action, the clip is one of the few moments that acknowledges the wider world. (The irony of their relaxation being so saturated in violence cannot be missed, couching a Haneke-style media critique in a film set in the Third World). But Van Damme’s visage also points to a precise pun on the title: universal. Combined with the film’s lack of a specific geopolitical locale, Rebelle posits an uncomfortably tidy “we are one” element.

This problem is not unique to Nguyen’s film—see similar discussions surrounding Claire Denis’ White Material (2009), which also eschewed local specificity while grasping at allegorical meanings—but this does not excuse them. Beyond the issues of false equivalencies (i.e., whether it’s drawing them), there is an ethical imperative in assuming another’s tale of suffering and transposing it to a collective—especially when that collective is a (predominantly festival) theatre audience. While the film might have gone the “misery porn” route (and some might say it does), the way in which Rebelle wears magic on its sleeves implies the film edges towards the other end of a myopic spectrum: feel-good positivity.

Additionally, as the film is so visually accomplished (thanks to Nicolas Bolduc’s cinematography), its beauty raises the question of the politics of magic. In a drugged state, Komona leans backwards marvelling at the treetops overhead, which blur into a blanket of rustling green. Though it’s an aesthetically splendid sequence, to note such feels unethical given the narrative circumstances. It is these moments which recall similar problems with Beasts of the Southern Wild and other films which insist on blending the magical with their tragic realism: a form of liberal indulgence, it hinges on the perceived notion of seeing the right “art” film—one whose politics are comfortably aligned with a left-wing status quo—while never being forced to deal with an uncomfortable reality. It’s a parlour trick, creating the illusion of activism while passively watching. Dark arts, indeed.

Room 237 (Rodney Ascher, USA)—Vanguard

By Quintín

Before watching Room 237, I realized that there are two things that I haven’t cared much about for many years. One was Stanley Kubrick’s films. I felt bored by Spartacus (1960), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Barry Lyndon (1975), irritated by Paths of Glory (1957), Dr. Strangelove (1964), and A Clockwork Orange (1971), and indifferent to the rest. Kubrick seemed to me to be one of those megalomaniac filmmakers, whose genius is apparent for some and dubious to the rest. I never had patience for Kubrick and his stories that don’t flow, and considered him rather weak as an intellectual. I still consider the famous and so highly regarded opening scene in 2001 as fraudulent, and I cannot imagine why that childish, ugly thing with monkeys, bones, and a monolith makes so many people imagine that they are witnessing the birth of mankind. Anyhow, when I got old and Kubrick died, I was completely thrilled by Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Suddenly, I realized that Kubrick, as no filmmaker before him, had hit on the connection between sexual repression and American democracy.

The other thing I can’t stand is interpretation. Not that I’ll start quoting Susan Sontag, but I have neither the patience nor the will to look for hidden meanings in the movies. If a filmmaker bothers to plant some secret clues to be rescued by some clever viewer, I wonder why anybody would go to that kind of trouble on both sides of the process. Films should be made to be seen only once, with no second-guessing.

Then I bumped into Room 237, a documentary about hidden meanings in The Shining (1980). I saw The Shining at the time of its release and have always thought of it as another visually pompous but boring and insubstantial Kubrick movie, a failure as a genre film and not interesting as a thesis about whatever’s going on underneath its plot. And suddenly, I was enlightened. I’m not exactly sure why or in what respect, but I came out of Room 237 admiring Kubrick, regarding The Shining as a sort of masterpiece, and reconsidering my phobia towards interpretation.

Since The Shining opened, theories about what Kubrick really was after piled up, as with few films in history. Room 237 takes the five most famous (or infamous) of them, makes the authors speak in the background without introduction, and mixes their voices to produce the impression that there is only one narrator and one unified theory that explains everything. That choral voice speaks over the exact passages—slowed down and otherwise manipulated via editing—where the theory applies.

In this, Room 237 might seem to advocate such against-the-grain readings or just the opposite, a kind of mock documentary that makes fun of Kubrick and the exegeses directed to his oeuvre. But there’s also a third possibility: that the validity of interpretations is impossible to decide or even irrelevant, that it is not the truth that counts in each stab at finding a deeper meaning, but rather the process of guessing. Room 237 strongly states that cinema is inseparable from meaning since the moment we entered the era of portable formats, before which halting the projection, going backwards, or freezing a frame were practices only available to editors or film scholars.

Viewing a film is becoming more and more inseparable from returning to it and playing it endlessly. What’s even stranger for the old-critic mentality is that meaning is no longer fixed as a result. Thanks to technology, a film is not the same object as it was in the past, and the game of meaning attains its true goal, which is not to locate a set of equivalences between scenes and the secret that lies beyond them but, on the contrary, to liberate ambiguity and contradiction. That’s what Room 237 does; together with The Shining, it does in two steps what Fritz Lang could do in a single camera movement. But maybe Kubrick is like Chateaubriand, who left his 2000-page masterpiece, Mémoires d’outre-tombe, to be read after his death. He is making films from the grave, like one of The Shining’s jolly ghosts.

Logically enough, Room 237 also requires replay and interpretation, and the film tells explicitly from the get-go that it’s leaving behind its own clues. There is a clear sign of that at the beginning—or rather a sign that makes clear the movie is making signs. The word “Europe” is superimposed over a scene taken from Eyes Wide Shut where Tom Cruise stands in front of a theatre. That scene is of course supposed to take place in New York, but Eyes Wide Shut was almost entirely shot in England. Is Room 237 cheating on the viewer or telling an inner truth? Cruise goes into a place which looks more like a cabaret than a theatre, seemingly to attend a screening of The Shining—he’s being used as a surrogate for one of the film’s narrators. When he emerges he’s literally turned into Robert Redford from All the President’s Men (1976).

But in the meantime, the voiceover says that while watching The Shining, the narrator grabbed the theatre seat with his right hand. But we see a guy (neither Cruise nor Redford) grabbing a theatre seat with his left hand. Then, Redford transforms into Cruise again, and the voiceover says that he sat in the left back seat of his car, but Cruise is sitting on the right. Maybe these confusions between left and right and shifting identities have to do with mirrors, and Room 237 is mirroring The Shining, which has something to do with mirrors. That opening scene can be thought of as a parody, but also as an homage to seeming continuity mistakes that riddle The Shining, despite—or perhaps owing to—Kubrick’s propensity for dozens of takes. These little errors are more apparent since we’ve been able to watch films on computers, and they function as openings for strange explanations to sneak into a movie. Cinema is no longer solid, but rather like Swiss cheese, full of those holes through which potentially endless interpretation flows.

In a way Room 237 is a joke. But it’s more accurate to say that Ascher is having fun and inviting the viewer to have fun, as well. Of course there is something humorous about it, as there is something humorous and silly in the theory from one of the film’s subjects, Jay Weidner, stating that Kubrick secretly worked for NASA faking the Apollo 11 landing. Unless he’s also a fabrication, somebody called “Jay Weidner” has been insisting on this point for years (thanks to the Web, we don’t even know if people are real any more; in the film, Weidner only exists as a voice on the soundtrack). But when Room 237 illustrates that Danny wears a sweater with an Apollo 11 theme—and is shown in one shot, outside room 237, “blasting off” as he rises to stand—the idea starts to sound plausible. And thus the other theories and their demonstrations via photograms and scenes that refer to the mass killing of Native Americans, the Holocaust, and especially the idea that The Shining is about “pastness”—the unavoidable impingement of the past on the present—look not only plausible but rather convincing. The manipulation of the film material, the juggling of meanings, the associations connecting truth, memory, and film in Room 237 add up to something very enjoyable, as a kind of a fresh pleasure in film viewing, which is not exactly the same as the essay-film format, nor the usual patchwork in the found-footage genre. Made with no clear tradition behind it, Room 237 invites us to a dance with a cinema that is daring and free.

I watched Room 237 twice. In between, I watched The Shining on my computer and rather loved it, found it scary and intriguing. Its obvious weirdness (which so strongly anticipates David Lynch), those ambiguities, the unsolved side mysteries and plot holes, all of which made me angry 30 years ago, added to a pleasure that Room 237 undoubtedly paved the way for. Among other things, thanks to Room 237, I saw how close the film was to Eyes Wide Shut.

As If We Were Catching a Cobra (Hala Alabdalla, Syria/France)—TIFF Docs

By Michael Sicinski

Less a fully-formed documentary than a collection of clips and interviews with the glue of World History holding them together, As If We Were Catching a Cobra could have been shot with the lens cap on and would still be of interest. This cannot excuse its shortcomings, however. Begun shortly after the revolt against Mubarak in Egypt and the still-roiling unrest in Syria, Alabdalla’s film takes an unusual angle on typical issues regarding freedom of the press (or lack thereof) in totalitarian Arab states by focusing not on conventional journalists, but cartoonists. Trouble is, we actually see very little of the artwork: instead, Cobra consists overwhelmingly of talking-head interviews with cartoonists, journalists and art dealers, who provide the expected explanations of why these somewhat oblique images (the ones we do see) can enter the public domain in ways that more explicit commentary cannot. And we see Alabdalla mousing through thumbnails of even more cartoons on Google. One of the primary interview subjects, Syrian writer Samar Yazbek, provides semi-poetic refrains regarding her eventual exile, delivered over such pedestrian imagery as gathering storm clouds. Cobra is the sort of documentary that has “good intentions” stamped all over it, but fails on some very basic levels.

Beyond the Hills (Cristian Mungiu, Romania/France)—Masters

By Robert Koehler

The dilemma of a scenario based on the effect of a sustained single dramatic tone, and attached to a single dramatic idea, isn’t one to dismiss lightly, and the surest proof of the dangers inherent in the strategy are on vivid display in Cristian Mungiu’s Beyond the Hills. In his first feature since his Palme d’Or-winning 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), Mungiu relies on a variation on a theme: How do female friends respond when an oppressive system applies extreme constraints on their liberty? This is a great and rich theme, in fact, focused enough to concentrate a filmmaker’s (and viewer’s) mind, universal enough to apply to innumerable situations, inherently dramatic and cinematic enough to justify a movie.

So why does Beyond the Hills fail where 4 Months etc. largely succeeded? The communist system surrounding the young women in 4 Months was largely invisible yet ever-present—both qualities proving essential to the drama’s full effect. The system in the new film is, perhaps unavoidably, in your face: an Orthodox monastery populated by nuns and ruled by an imperious male priest, where Voichita (Cosima Stratan) devoutly serves while welcoming in her friend and apparently ex-lover Alina (Cristina Flutur). The place is obviously and immediately unwelcome to cosmopolitan Alina, and she returns the dislike, raising the natural question of what possessed Voichita to think that Alina would possibly be able to tolerate the near-medieval environment. Mungiu sets up an absurd stacked deck of dramatic conflicts to play out a rote re-do of his now-familiar formula, a far cry from the insidious logic of his earlier work’s psychosocial parameters.

Dust (Julio Hernández Cordón, Guatemala/Spain/Chile/Germany)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Mark Peranson

Guatemalan filmmaker Julio Hernández Cordón has found an original way to explore the contemporary after-effects of civil unrest: his proposition is that the Guatemalan civil war that lasted from 1960-1996 has created a kind of sickness in society, and thus infects every interaction. A complicated character in a complicated film, Juan (Agustin Ortíz Pérez) is unpredictable and choleric, prone to dramatic suicide attempts and violent outbursts—most of them directed at the man responsible for turning his father over to the military, and who still lives just down the street. About the same age as Juan, Ignacio (Eduardo Spiegeler), along with his pregnant wife Alejandra (Alejandra Estrada), is making a documentary about indigenous survivors of the conflict who are looking for their lost family members. Ignacio considers Juan and his mother Delfina perfect subjects to follow as they search for the remains of Juan’s missing father, whose picture Juan has never even seen. Juan, however, is far from convinced. In his fourth film (and second this year), Cordón continues to grow as a director, and structures his film on the intersection between these two somewhat paralleled individuals, one who subsists in anguished purgatory, the other who seeks to understand it—but is bound to fail. An unsettling and at times disturbing work that bears scars from its making, Dust is about the unremitting desire for vengeance and the inability to escape the past—especially when you’re confronted with it every day.

It Was the Son (Daniele Cipri, Italy/France)—Special Presentation

By Mark Peranson

Set in Palermo, tangentially related to the Mafia, and with a featured cameo by a dwarf, Daniele Cipri’s solo feature directorial debut has that much in common with his groundbreaking and subversive works with Sicilian ex-partner in crime Franco Maresco (none of which played in Toronto). But the extent of the grotesquerie on view here lacks all redeeming qualities. Narrated by a semi-autistic loser while sitting in a post office (played by, of all people, Pablo Larrain’s favourite actor Alfredo Castro), It Was the Son is a constant assault and battery of sub-Sorrentinian baroquery built around a truly horrific lead performance from Toni Servillo. As Nicola, a barely employed, shriek-prone, salt-of-the-earth schlemiel, Servillo physically resembles a retarded version of Cagney and Lacey-era Harvey Atkin and presents an extremely unappealing depiction of Italian patriarchy which, I am sure, is to a certain extent intended and is more than convincing. Around him, Cipri assembles a collection of unpleasant, mainly overweight idiots—some of which he’s imported from Cipri-Maresco productions—and frantically moves his camera over and around their most revolting aspects. Based on a novel, the screenplay runs these losers through a basic three-act storyline heavy on “the funny” that takes 90 useless minutes to resolve itself: daughter is killed by a stray bullet (shot directly at her in close-up, it seemed to me), and the extended family is promised money from the government; while waiting for millions of lire (I guess which makes the film a period piece), they run up debts and have to borrow money to cover the money they don’t yet have; they get the money and Nicola decides to spend what’s left on a swanky Mercedes which becomes, to quote the press kit as I don’t care to write any more about this film, “more than a symbol of wealth, it becomes the symbol of the Misery of Wealth, an instrument of ruin and defeat.” Misery, ruin, defeat: that about sums it up.

Jackie (Antoinette Beumer, The Netherlands)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Blake Williams

Jackie is a hammy and altogether unlikable film that gets by on some charming, probably unintentional absurdities. The narrative involves Dutch twins Sofie and Daan (played by real-life sisters Carice and Jelka Van Houten) who venture all the way over to New Mexico so that they can reunite with their estranged mother (Holly Hunter) and drive her to rehab (those familiar with Hunter’s particular brand of stinkface will be relieved to know that this movie is essentially 100 minutes of it; if not literally, then at least tonally). Once the sisters have the crippled and cranky Jackie loaded up in a run-down mobile home, the film becomes a variation on the Alexander Payne travelogue, where geographically-specific misfortunes and kitschy Americana initiate a range of dramatic and comedic hijinks (Daan’s affinity for bluegrass would certainly count as the latter). As the trio treks ever so slowly across the state, Beumer underlines the ways communication and distance (physical and emotional) impact each other; the twins interchangeably speak Dutch and English depending on their desired level of privacy from their mother, while Sofie’s Skype calls to her colleagues back home cut out at the worst possible times (a complication that arises as they stray too far from the network signal). Though intended as a testament to the human capacity for reconnection and familial reconciliation, the characters’ emotional transitions are ultimately too rushed and their motivations too disingenuous for Jackie to be more than a weird and mildly amusing Holly Hunter showcase.

Motorway (Soi Cheang, Hong Kong)—Vanguard

By Christoph Huber

Having established himself as one of Hong Kong’s key genre auteurs in the previous decade, Soi Cheang delivers down-and-dirty, homegrown analogue action pleasures in Motorway—produced, like his previous film Accident (2009), by Johnnie To’s Milkyway company—before unleashing his first big-budget, Mainland-shot extravaganza with a remake of The Monkey King. Even better, although Motorway is allegedly inspired by his love for the racing scenes of ’70s American cinema, Soi Cheang grounds his car-chase vehicle in the venerable tradition of the Shaw Brothers martial arts film.

Shawn Yue stars as a brash youngster in the “Invisible Squad” of the Hong Kong police, a hand-picked unit of top drivers in charge of cracking down on illegal racing and hunting down fugitives. When he finds more than his match in a preternaturally skilled getaway driver (Guo Xiaodong), he gets special tutoring from the squad’s hitherto risk-averse, close-to retiring veteran (Anthony Wong). Wong alone, radiating supreme sifu-ness even as he mostly sits around in the film’s first half, smoking and drinking noodle soup cups, would be worth your ticket, but Soi Cheang also demonstrates consummate skill in carefully escalating his kinetics in rhythmic cascades as the demands of the missions increase. Easily meeting contemporary high-octane needs, Soi Cheang also maintains the high-speed legibility, rugged poetry, and abrupt grace of the HK tradition, evidenced in a barrage of small details: a sudden zoom-in, or a close-up of a branch quivering in the headwind accentuating the flow of the chase. That the plot is as lean as the title only emphasizes that Motorway is part of a nearly lost art: a world and its inhabitants expressed almost exclusively through action.

The Paperboy (Lee Daniels, USA)—Special Presentation

By Richard Porton

Lee Daniels’ follow up to the cringe-worthy Precious (2009) might lure in unsuspecting spectators intrigued by the prospect of enjoying a ludicrous guilty pleasure. Unfortunately, Daniels doesn’t have the directorial chops to even make this pulpy adaptation of Pete Dexter’s novel coherent, let alone enjoyable. The convoluted narrative is an admixture of melodramatic tripe and pseudo-political ruminations on lingering racism and homophobia during the late 1960s. When crack Miami Times reporter Ward Jansen (Matthew McConaughey) returns to his hometown to investigate the potentially trumped-up conviction of a vicious criminal named Hillary Van Wetter (John Cusack) for the murder of a bigoted local sheriff, sub-Tennessee Williams obsessions are unleashed. Much to the film’s detriment, the implications of this murky crime, which could have made for a decent neo-noir, are subsumed by various silly subplots. In a manoeuvre that Daniels apparently views as subversively campy, The Paperboy becomes preoccupied with the infatuation of Ward’s kid brother Jack (Zac Efron) with Charlotte Bless (Nicole Kidman), a dimwitted exhibitionist plagued by a bewildering crush on Hillary, while towards the end of the film it’s revealed that the seemingly macho Ward is actually sexually involved with Yardley (David Oyelowo), his earnest colleague from the Times. But given the film’s flat-footed pacing, it’s difficult to muster much interest in these crass attempts at titillation. At Cannes, much ink was spilled to either celebrate or lampoon a scene in which Kidman urinates on Efron to relieve the pain of a jellyfish sting. This half-baked controversy sums up the vacuity of a film that desperately wants to be scandalous but is merely an inchoate mess.

The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Stephen Chbosky, USA)—Special Presentation

By John Semley

There’s something noxious about Stephen Chbosky adapting and directing his own adaptation of his own young adult novel; it’s as if he deemed the material—saccharine dross regarding the growing pains of tweendom, time-stamped with the requisite Smiths- and Sonic Youth-referencing soundtrack—too deeply personal to cede to someone else. But then, who else would bother?

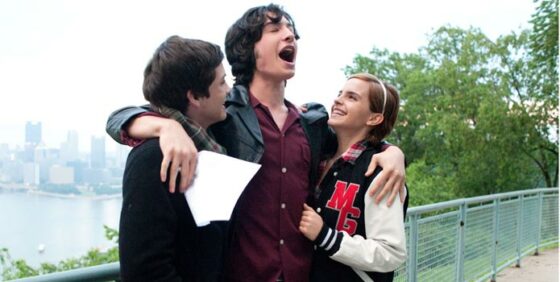

Published in 1999 (by MTV), The Perks of Being a Wallflower struck a chord with certain narrow demographics, either struggling through the lonerish trials of grade nine or looking to have those past struggles rosily romanticized in hindsight. In the film, Logan Lerman plays Charlie, a runty high school freshman whose superficially crippling shyness is forgotten as soon as he falls in with the older, cooler senior-class misfits. Chief amongst these crudely sketched character wisps are Ezra Miller’s flamboyant queer prankster (in love with the deeply closeted football stud, no less) and Emma Watson’s pixie-ish music snob (who has heard of The Smiths, an obscure band in Pittsburgh ca. 1991, despite a number of top-charting albums), prime movers of a lively Rust Belt subculture constituted by a not-so-underground railroad of house parties and Rocky Horror Picture Show shadow casts.

There are intimations of Bad Things in Charlie’s past, not-so-subtly suggested by flashbacks to a questionably kind aunt and family members consistently asking him with strained heavy-handedness how he’s feeling and if he’s okay and all that. The film’s approach to mental illness is as hokey as its depiction of countercultural coolness: barely skimming the surface while making a big, overstated to-do about doing so. (It doesn’t help that Chbosky stages his string of After School Special scenarios with stupidly dizzying camera angles to suggest, you know, a fractured mental state.)

It’s also a bit unclear which nostalgia gap Chbosky’s lobbing his film at. Is it for the suffering high schoolers? The older set reflecting on their own self-persecution? Or those looking to reignite flickers of beautiful loser romanticism set off originally by the book? Whatever the case, there’s likely no shortage of potential viewers eager to gobble down this piffle, vintage indie soundtrack and all.

A Royal Affair (Nikolaj Arcel, Denmark/Sweden/Czech Republic/Germany)—Gala Presentation

By Scott Foundas

At the end of the 18th century, the social and cultural reforms of the Enlightenment have spread across Europe—save for Denmark, which remains very much in the intellectual Dark Ages, presided over by the childlike, possibly mad monarch King Christian VII (remarkable newcomer Mikkel Boe Foelsgaard), who’s markedly less interested in his newlywed queen, Caroline Mathilde (Alicia Vikander), than in his faithful pet hound. Enter physician and Enlightenment thinker Johann Struensee (Mads Mikkelsen), who accepts the King’s invitation to become his personal physician and soon, having “cured” his patient, becomes something more: brother, confidant, advisor, and ultimately a revolutionary force inside the staid royal court. Then the power starts to go to Struensee’s head, as do the come-hither stares of the lonely Queen. Based on true events, director Nikolaj Arcel’s bracingly smart, compulsively entertaining historical drama traces Struensee’s remarkable ascent, the sweeping social changes he managed to enact (freedom of speech and the press, mass inoculations), and his equally dramatic fall from grace. Handsomely directed, with an emphasis on the era’s grimy reality rather than the frilly extravagance of most period films, A Royal Affair transforms a little-known episode of European history into a timeless study of intelligence and progress at odds with stasis and superstition. The performances are uniformly first-rate, especially Foelsgaard, who won Best Actor at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, where A Royal Affair also garnered the Best Screenplay award.

Shores of Hope (Toke Constantin Hebbeln, Germany)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Kiva Reardon

It’s 1984 in the German Democratic Republic, and dockworkers Conny (Alexander Fehling) and Andreas (August Diehl) are friends seeking freedom on the high seas. Hoping to set sail and jump ship at the first Western port, the pair fall in with the Stasi, offering to rat out their foreman for placement on a boat. Something goes wrong (the details matter very little) and Conny must flee, along with his Vietnamese girlfriend, Mai (Phoung Thao Vu). They hop a fence; she makes it, he goes to prison. But—never fear!—love, friendship and other meaningless tropes prevail. The movie-of-the week plot aside, Shores of Hope’s visual aesthetic may be summarized in a brief sequence in which Andreas lies in the hospital after an accident. With the Stasi on route to pay him a visit, lightning illuminates his darkened room as ominous music plays—bet they aren’t bringing him flowers! Laughably conventional (complete with a marriage proposal in a haystack), Shores of Hope drones on and on in this manner, adding layer upon layer of meaningless complication to its flimsy plot. Feeling as long as the decade it spans, it makes one ardently wish for the inevitable moment when the Wall will come down, along with the proverbial curtain.

The War of the Volcanoes: Bergman and Magnani (Francesco Patierno)—TIFF Cinematheque

By Phil Coldiron

Ostensibly a 52-minute gloss on the whirlwind romance between Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini, and the pair of dueling Aeolian-set productions that sprung up in its wake—Bergman and Rossellini’s Stromboli vs. hired gun William Dieterle’s Volcano, starring Rossellini’s ex, Anna Magnani, and instigated by cousins claiming RR had stolen their story— Francesco Patierno’s The War of the Volcanoes turns out to be a more curious thing than the E!-ready pabulum my own gloss maybe makes it sound like. Working with an array of archival material, ranging from feature-film footage to home movies, newsreels, and stills, Patierno and editor Renata Salvatore quilt together a knotty, discursive account of the passions and intrigues flowing among everyone involved (which also includes Howard Hughes, whose name you really haven’t heard until you’ve heard it pronounced in Italian). As storytelling, its exquisite—at least until the final minutes, when both films prove to be critical and commercial flops, the romantic intrigue fizzles away, and the voiceover politely tells us that it’s always been more about the islands anyway. Less exquisite, and of more interest, is the paranoid feeling that springs from all this quilting: ripped out of context and carefully arranged in this new narrative, every moment gets weighted with a retroactive destiny. So, for example, when Rossellini flies off to chase down Bergman in America without so much as a goodbye, we’re given footage of Magnani from Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948) demonstratively longing for her man. It’s effective for Patierno’s story, but like many comparable examples here, it leaves all that emotion a dried-out inevitability, just another beat in a good yarn.

cscope2- « Previous

- 1

- 2