TIFF Day 8: Wavelengths 4: From the Inside Out

By Andrea Whyte

Black TV (Aldo Tambellini, USA, 1968)

Burning Star (Josh Solondz, USA)

When Bodies Touch (Paolo Gioli, Italy/France)

Ritournelle (Christopher Becks, Peter Miller, Germany)

Watch the Closing Doors (Jim Jennings, USA)

View from the Acropolis (Lonnie van Brummelen, Siebren de Haan, The Netherlands)

De la mutabilité de toute chose et de la possibilité d’en changer certaines (Anna Marziano, France/Italy)

Reconnaissance (Johann Lurf, USA)

The final installment of the Wavelengths shorts programmes, From the Inside Out, opens with influential media artist Aldo Tambellini’s anxiety-ridden Black TV (1968), a treatise on the uneasy politics and pervasive fears that permeated 1960s America. Culling from archival news footage and displayed in 16mm split-screen dual projection, Tambellini’s screens act as distorted television sets, playing off each other’s frenetic images and invasive snow. White noise mutates into an electronic heartbeat as the images begin to pulsate, creating a dynamic force field. Close-ups of faces frozen in shock and terror are matched by choked voices and layers of screams, repeated variations of “Senator Kennedy has been shot” and exclamations of “Oh God! Oh no!” Social anxiety invades the perceived personal safety of the home through the medium of television, and Tambellini implicates the community watching these images of violence, forcing viewers to acknowledge that they are no longer merely witnesses but active participants in this state of unrest.

Perhaps the most exciting discovery of the evening, Josh Solondz’s Burning Star was produced during the filmmaker’s residency at the now defunct Experimental Television Center; several days of experimentation with audio and electronic video synthesizers resulted in this single four-minute extracted piece. Solondz Composing the symphonic implosion/explosion of a twelve sided star, Solondz makes the eye of the star control the viewer’s line of vision, forcing focus towards the centre of the screen—a directional tactic that allows for the film’s perpetually brilliant surprises. As soon as the centre star draws one in to its hypnotic stasis, the patterns of its dynamic counterparts have changed in their motion, colour and size; finding oneself at the locus of an entirely new movement, the cycle of disorientation and absorption begins again. Throughout, an audio track of synthesized noise intensifies the motion, appearing to follow the logic of the visual pattern. When asked about the relationship of the audio to the images in the conversation that followed the screening, Solondz revealed that this sound physically determined the images we experienced. It is also worth noting that the film’s title refers to Kenji Onishi’s infamous documentation of his father’s cremation, A Burning Star (1998); while the two films appear to share little in the way of formal similarities, Solondz’s dedication of Burning Star to his own father reveals a perhaps more personal significance to this homage.

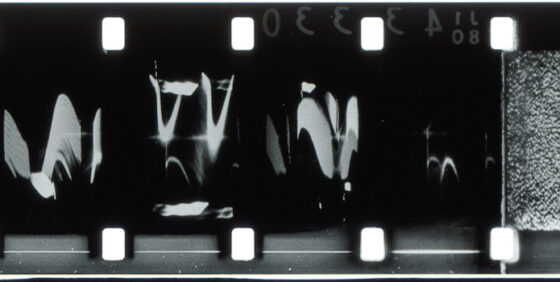

The highlight of the evening’s programme for me was innovative Italian director Paolo Gioli’s When Bodies Touch. Gioli takes the explicitly erotic imagery of pornography, a genre which in its very nature acts as a public revelation (and potential defamation) of the body, and transforms the act of copulating on film into an intimate, nearly secretive endeavour. The images of the couple tease as they dance across the screen, Gioli refusing to reveal their true nature and hence blocking any gratification that may derive from the sexual imagery. Gioli is interested in technological innovation and experimentation with the photographic apparatus; he works with alternative home-made cameras, placing himself almost in the pre-cinematic tradition. When Bodies Touch was captured with a pinhole camera, which emphasizes the nature of shadows in the photographic image, the freezing of light revealing traces of a moment which once was. Gioli further teases us with the framing, offering only offset segments of an image and slowing or halting the momentum of the copulating couple, an act that serves to de-eroticize the material. The edges of the film strips strike through the film on a horizontal plane, wiping away the photographed images and filling the screen with light. The consistent obstruction of the erotic nature of Gioli’s imagery by the play of the physical film material serves to transform the public nature of the pornographic film, in which sexual acts are filmed and consumed by an audience, into an intimate secret, concealed and revealed by the film strip itself. The obtrusive movement of the film strips expose the invasive nature of our own desire to see. The bodies here are not captured for our pleasure but are instead experiencing their own, veiled and protected by the motion of the film and the limiting gaze we are permitted.

Working independently in two different cities, Peter Miller and Christopher Becks composed the elegantly intimate corps exquis Ritournelle: Miller created the melodic yet haunting soundtrack which Becks used as the inspiration for the 16mm film, set entirely in the confines of Becks’ Berlin apartment. The subtle beauty of light beams bouncing off the surfaces of the apartment’s rooms slowly reveals the spatial context. Circles of white light dancing across the darkness of the screen give the feeling of awakening in the early morning to glimpses of daylight sneaking through shrouded curtains. The audio track works in harmony with the soft imagery to create a lovely warmth, a respite from the frenetic action of the first three films which sets the tone for the quiet, focused observations that pervade the second half of the programme.

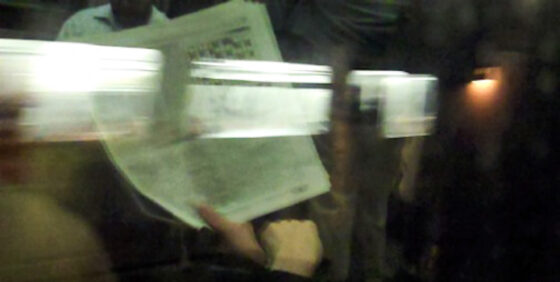

Well-recognized for his city symphonies, Jim Jennings moves underground with Watch the Closing Doors, a short video work made on a flip camera. Jennings films other passengers during a single journey on the New York City subway, focusing his attention on the commuters’ faces as they wait out their travel and the encroaching platforms as the train approaches its various stops. Synchronized sound captures the conductor’s voice as he offers near incomprehensible advice, including the oft repeated phrase “Stand clear of the closing doors.” Jennings’ empathy for his subjects derives from his own identification, as he is merely one of the many commuters who are experiencing this journey. The public space is transmuted into a private fixation, as Jennings clearly takes pleasure in spontaneously and surreptitiously utilizing this flip camera to capture his journey; but while this experiment may very well have remained private, by structuring the captured footage into a film Jennings makes the journey public once again. Most striking about the piece, however, is the sense of community Jennings implicitly creates: it is often easy to forget that the individual act of getting from point A to point B becomes a communal one through the use of public transportation. Watch the Closing Doors emphasizes the inescapably collective nature of our interactions in the public sphere, and exposes our false sense of individual privacy.

Shot on 35mm, View from Acropolis is one of a series of films by Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebran de Haan that explore Europe’s cultural and political history through sites and artefacts of cultural memory. The filmmakers travelled to the original site of the Acropolis (the monument itself is now housed in a Berlin museum) and attempted to capture the traces of memory that dot the landscape. The film registers its politics through observing the emotionally charged nature of the land itself: eroded fragments of the ruins embedded in hills are overgrown with weeds; jagged ditches cut through the land like deep scars. Locals observed far below move through small towns and traverse dirt roads, continuing their lives in the shadow of the absent monument. Fierce winds dominate a synch-sound audio track, hypnotic to the point where they nearly transform into human whispers, contributing to the eerie, pervading sense of absence. There is little movement, with the exception of the windblown trees and weeds within the frame. Instead, the filmmakers meditate on the site and its relationship not only to the country of Turkey but to the history of European geopolitics.

This idea of the relationship between memory and place particularly dominated the second half of the programme, which focused on cultural and political inferences that are inseparable from the geography of landscape. Anna Marziano’s De la mutabilité de toute chose et de la possibilité d’en changer certaines takes the filmmaker to Abruzzi, Italy, the site of a devastating earthquake in 2009. Capturing the damaged structures and landscapes of the town, Marziano’s film moves beyond documentary observation as it actively participates in a project to rejuvenate the public sphere of the town. By having locals read passages from a variety of the texts she brought along in her journey, Marziano unites her subjects through the creation of this film, aligning their private experiences and having them speak again as a community. In the question-and-answer period following the screening, Marziano lamented the loss of public spaces that the town experienced through the earthquake; schools, community centres and churches were destroyed, and residents had so far only focused on rebuilding their private dwellings. Marziano attempted to propel the desire for revitalizing communal spaces to the forefront, seeing the return to the public sphere as necessary to a return to normality for people whose lives had been severely disrupted. Through working directly with her subjects on this film, Marziano was able open up a dialogue about change and how we adapt. What results is a quiet and inspiring film on the effects of uncontrollable change, and the small actions individuals may take to reclaim their lives and overcome the scars of their recent history.

In his meditative exploration of the Morris Reservoir is Aszura, California, created during a residency at the MAK Center for Arts and Architecture in L.A., Austrian artist Johann Lurf uses a nearly imperceptible moving camera to play with our visual perceptions and reveal the architecture of space. The site itself was once used for testing torpedoes, and Lurf’s film serves to present both the current state of the dam at night, as well as explore the scars left on the site from its military history. Initially static shots of the manmade structure and the ragged topography of the surrounding landscape transform as the camera’s subtle movements reveal the dimension of the space, forcing the eye to acknowledge the depth of the monumental structures and land masses. The subtle, inquisitive dynamism of Reconnaissance makes for a fitting conclusion to a programme which consistently challenges the concept of fixed perceptions and an immutable world.

Andrea Whyte