TIFF 2015 | Love (Gaspar Noé, France)—Vanguard

By Blake Williams

Originally published in Cinema Scope 63 (Summer 2015).

It’s been both amusing and disheartening to watch fellow critics lash out against Argentine-born “French extremist” Gaspar Noé’s new movie, a 3D porno un-ironically titled Love, for failing to achieve such “good movie” goals as “acting excellence,” “believable chemistry,” or “naturalistic dialogue.” Admittedly, Love’s execution of these basic tenets of narrative filmmaking is shoddy in comparison to other recent attempts to introduce frank sexuality into upper-middlebrow markets, such as Nymphomaniac (2013) and L’inconnu du lac (2013). Then again, Love isn’t really aspiring to narrative-movie objectives. By this I don’t mean there isn’t a plot; there is, and it’s indeed a very Noé-esque one, backtracking through a relationship’s trajectory in order to rediscover a blissful origin. But the way that Love works with time isn’t horizontal as in traditional narrative cinema; linear, cause-and-effect relations are hardly its chief concern. Rather, it manoeuvres through its arena of texture, light, and bodies—as Noé’s cinema so often does—according to jagged, up-and-across movements, starting and pausing its plot in a manner more characteristic of lower (pornographic) or higher (avant-garde) cinematic traditions, allowing the erotics, spectacles, or poetics to suspend our attention in bodily experiences. To watch one of Noé’s movies is to have been made hyper-aware of cinema’s faculties for manipulating our perception of time via components that lie outside of plot progression, character arcs, and acting abilities.

All of which is to say that if we’re going to pick on Noé’s new movie, let’s at least do it in terms that are relevant to what it’s actually trying to do. Love is, said and done, a 3D pornographic film running 135 minutes, with at least half of that running time spent watching a trio of young, conventionally attractive individuals (who either are or should be non-actors) having unsimulated sex. Having spent his career investigating man’s most primal and animalistic instincts, in Love Noé aims to grapple with the often contradictory correlation between the wild and woolly libido and that perhaps more conservative urge to settle into a monogamous family unit, both steered more or less by that crazy little thing called love.

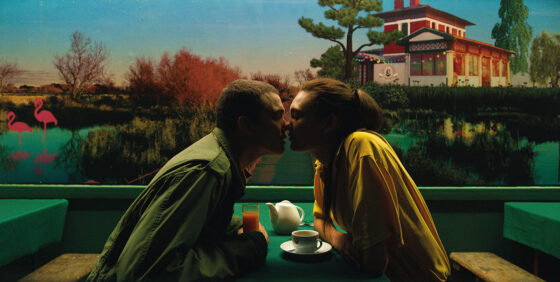

The single dominant aesthetic gesture in this film composed almost entirely of static, medium two-shots (apparently weary of inducing 3D headaches, Noé was interested in little other than pleasure here) is its use of stereoscopic photography. A number of shots are filmed from overhead, looking down at the characters in the cramped, usually sunless interiors, and occasionally these compositions are framed—usually during the lovemaking scenes—so that their bodies are coming in from the top of the frame rather than the bottom, creating a slight disorientation with respect to gravity. All of the shots are conjoined by brief seconds of black, as if to suggest a long blink or a momentary lapse in consciousness, à la Enter the Void (2009). But save for a couple of quasi-psychedelic interludes that appear to be paying 3D homage to Jordan Belson and Anthony McCall, Love plays it pretty straight; for better and worse, La région sexuelle this decidedly is not.

Love’s employment of stereoscopy, then, is curious in that Noé has essentially appropriated the technology without any apparent ambitions of subverting or pushing against its usual functions. He said at the film’s Cannes press conference that he wanted to try out 3D because it was like a new game for him to play and that it is a “childish” medium, and in some sense he’s right. Stereoscopic cinema has never had an opportunity to mature, because all the fads that have ever brought it into the market have been so short-lived; when it periodically (re-)emerges, it can only function, like any novel cinematic technology, as an attraction—a show, a ride, a spectacle. For a myriad of technological and social reasons, this current 3D wave is the first that’s been sustained long enough for us to get a stereoscopic porno that we have the opportunity to take somewhat seriously. If last year, with Adieu au langage, we were finally able to see 3D’s voice crack, Love might be best taken as its first date: a dumb, awkward, unseasoned, and horny experience that is best forgotten in the long term but serves as a logical and necessary step for now. And while it should be noted that Love isn’t nearly the first 3D erotic picture—there were over two dozen of them made in the late ’60s and ’70s (some even in 70mm)—if you’ve had the misfortune of seeing any of the others, you’ll know that they represent the height of puerility in 3D cinema.

And speaking of puerility, Love certainly has its moments. To give an idea: the movie opens with a single-take shot of mutual handjobs being exchanged between Murphy (Karl Glusman), the film’s protagonist and ostensibly Noé’s alter ego, and Electra (Aomi Muyock), whose ex-boyfriend Noé (Gaspar Noé) runs the Noé International Art Gallery. A condom breaks while Murphy sleeps with his neighbour Omi (Klara Kristin), prompting a massive onscreen text to define Murphy’s Law, hence the character’s name. Movie posters decorate seemingly every domestic interior, effectively serving as a lowbrow equivalent to Godard’s internal citations. (These include, among others: Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom [1975], reminding us of a level of noxious sexual depravity graciously not on display here; Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein [1974], Paul Morrissey’s 3D Udo Kier-starring camp classic; and M [1931], though the one-sheet here is perhaps alluding not so much to Lang’s film but to Stephen Gibson’s M 3-D! The Movie (1976), an anaglyph Deep-Vision romp starring John Holmes and a guy running around in a feathery cock costume.) Then there’s Murphy and Omi’s baby, which they name Gaspar; some more praise for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); references to a trans woman as a “good compromise” for a hetero threesome because she has “some boobs and some cock”; a 3D cum shot shooting straight at us; and such pearls of wisdom as “Life is what we make of it” and “A dick has no brain.”

This film is, indeed, absolutely moronic. But Noé’s films can be so difficult to judge qualitatively because they’re so willfully, oppressively tasteless, while at the same time being so generative with respect to a broad range of social and aesthetic discourses. And so beyond the inanity, one could just as easily engage with its knotty sexual politics, which are facile but layered, or its lucid aesthetic stance, which forms a nervy sense of high-low dissonance in the context of the movie’s sketchy plot and dialogue. Thus, to return to the matter of 3D, there is a fundamental role that stereoscopy plays here that works both against and in tandem with the technology’s “childish” qualities. With modernity having turned the act of seeing into a primarily defensive mechanism, we should remember that stereopsis, the experience of three-dimensional vision, is a phenomenon only experienced by animals who have both eyes in front as opposed to on the sides of their heads, and is thus an attribute applicable mostly to predators—those animals that live in a sustained offensive mode. So if to see and detect depth is to re-evoke these predatory urges, our impulses to hunt, attack, and consume, then we might understand a greater or deeper function for stereoscopy in a sex film, especially one made by a man, and especially when that man is Gaspar Noé. In a sense, 3D and Noé were made for each other; Love just sees them getting it over with and making out already.

Blake Williams- « Previous

- 1

- 2