I Am Not Your Negro (Raoul Peck, US/France/Belgium/Switzerland) — TIFF Docs

By Steve Macfarlane

This past summer, I attended a screening and panel discussion hosted by the New Negress Film Society in Brooklyn; standing outside the venue afterwards, a flustered British gentleman took the evening’s general political timbre to task as follows: “I’m just a bit tired of hearing about the whole ‘white supremacy’ conversation. It’s so hostile!”

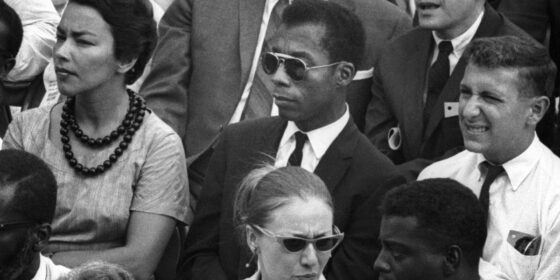

James Baldwin diagnosed a similar privilege-as-umbrage in his 1972 No Name in the Street: “If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have needed to invent, and could never have become so dependent on, what they still call ‘the Negro problem’.” The quotation is one of many threaded through Raoul Peck’s new I Am Not Your Negro, which is (at times, despite itself) a worthy companion to the two Baldwin docs of current record (Richard O. Moore’s Take This Hammer and Karen Thorsen’s The Price of the Ticket). Peck uses Baldwin’s 30 pages of notes for a book that never came to pass—about the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.—as a jumping-off point to explore his individualized epistemology of disenchantment during the now-hallowed “Civil Rights Era,” weighing lived experiences of racism against the official nomenclatures (then and now) that constitute “progress” in the American system.

But since the narration of Negro consists solely of Baldwin quotes read aloud by Samuel L. Jackson (using, here, a gravelly register that’s the opposite of the Snakes on a Plane voice he uses to pay his kids’ college tuition), this means what’s good about the film is what’s good about reading Baldwin, which is to say an entire constellation. Peck throws out a few interesting filmic propositions along the way, using clips from old movies to demonstrate the tropes by which the author, growing up, involuntarily measured his own selfhood against the gaping void of onscreen representation in 20th-century America. (The movies include John Wayne westerns, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the 1934 Imitation of Life, and Mervyn LeRoy’s Southern melodrama They Won’t Forget, featuring a sobbing black janitor played by Clinton Rosemund bullied into falsely testifying against a teacher from New York, in the service of good-ol’-boy reverse-classism.)

This extra-cinematic approach makes for a diverting enough complement, but more gripping still are, naturally, the clips of Baldwin’s appearances on American TV. While it’s beyond cliché to cite anything as “more relevant today than ever,” Peck finds grist in blotchy digital-video imagery from the last several years of #, protests and dashed hopes for police reform, to delineate Why Baldwin Matters Now. Given the undying strain of starter-kit bio-docs primed for Netflix streaming (or NY/LA release, typically for one week at a time), this polemicism is fairly welcome. Baldwin wasn’t just thinking ahead of the moment during the “Civil Rights Era”—whose officialese and in-hindsight tokenism is dissected in Peck’s film with considerable care—he was also ahead of ours. If I Am Not Your Negro lacks subtlety as an objet d’art, then, all I can say is America continues to live in hostile times.

Steve Macfarlane- « Previous

- 1

- 2