Heaven and Earth and Television Magic: The Cinema of Jesse McLean

By Tom McCormack

Toward the end of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, the narrator travels to Israel and forms an uneasy acquaintance with a young woman named Ruth. The episode is contrived so that Roth can stage a symbolic dialogue: one between traditional Jewish values and the values of humanist, American Jews; between the Old World and the New World; between the world of belief, order, and rationality and the postmodern world of moral chaos. Ruth tells Portnoy:

The way you disapprove of your life! Why do you do that? It is of no value for a man to disapprove of his life the way that you do. You seem to take some special pleasure, some pride, in making yourself the butt of your own peculiar sense of humor. I don’t believe you actually want to improve your life. Everything you say is somehow always twisted, some way or another, to come out ‘funny.’ All day long the same thing. In some little way or other, everything is ironical, or self-depreciating.

Forty-two years after it was published, the old world’s condemnation of the new still cuts to the quick, and perhaps now more than ever. Ruth/Roth was aware that self-deprecation is never far away from self-loathing; irony is the tool we use to describe our disapproval of our own lives. Of course, nowhere is the reign of irony more evident than in our relationship to popular culture. Ironic products meet ironic consumption; we make self-mocking parodies of self-mocking parodies. The game is to stay one step ahead: whatever it is, it can be out-meta’d. To complain about any of this is to be labelled worse than a prude: someone who just doesn’t get it.

But then pop culture would be boring—or even more boring than it is—if it didn’t seem perpetually to hold out the promise of its own undoing. Mass spectacle and shared experience always contain the promise of irony’s antidote. Get a large group of people together, get them all paying attention to the same thing, grooving on the same vibe, raving to the same beat, and it’s impossible not to find a flicker of hope for an experience larger and more unwieldy than irony and self-deprecation—something ecstatic, obliterating, something that takes you over by force, that brings you outside the self, roots you in the now, but simultaneously renders you unbound from the everyday world of objects and things and errands and routines.

So we sneer, ridicule, disapprove, and make sport of our disapproval. But there’s always a submerged longing for a deep communal outpouring of real feeling. On the one hand, we get things like internet trolls, Cory Arcangel, Auto-tune the News, and Gawker. On the other, nerd rockers, fanboyism, revivals of Charismatic Christianity, and Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign.

It’s this tension within contemporary culture that finds a voice in the movies of Jesse McLean. McLean works primarily with found footage, a natural outgrowth of her concern with irony and authenticity; to re-contextualize footage is to ask fundamental questions about its function within culture and automatically to cast aspersions on its original reception. McLean’s films expertly and violently toggle between outrageous, air-quoted self-doubt and outpourings of urgent, unnerving emotion. McLean’s most recent film, Magic for Beginners, is the culmination of the efforts that began with her three previous films, collectively called the Bearing Witness Trilogy.

The Eternal Quarter Inch (2008) finds us at an evangelical church gathering. “What would happen,” asks the preacher, “if the lights…were turned off?” We are then presented with various people slowly, meditatively walking through a suburban parking lot as if balancing on a tightrope. Onscreen text tantalizes us with a religious awakening: “Hysterical with joy.” “I felt something move.” “I’m a quarter inch away from eternal peace.” After this, McLean shifts us over to a montage of crowds spazzing out to milquetoast Christian rock. Is this really how people try to bridge the quarter inch between themselves and eternal peace? The longest segment of the movie is a kitschy animated graphic from a “mysticism video tape,” which pulses along to overbearing religious music. McLean lets this part play out a little too long for comfort; could we, at some point, get into it? The movie finds closure with another distended moment: people waiting around, in silence, after a Christian rock band has finished their song. The band seems set on letting the crowd ponder their own silence, and so we have to ponder ours as well.

Somewhere Only We Know (2009) is McLean’s most widely screened film to date, and it’s not hard to see why. The first section of Somewhere strings together moments from reality TV shows in which contestants wait to hear whether or not they have been eliminated. Like Oliver Laric’s web video 50 50 (2007), which strings together 50 different people singing 50 Cent songs, Somewhere Only We Know plays a dizzying game with likeness and difference. The first thing we notice about these clips is how similar these people are—it’s the repetition that forces us to recognize what makes each one individual. Each face is agonized with waiting, but, we eventually see, in idiosyncratic ways. As the expressions become differentiated, the agony starts to feel real. It’s only as a mass that these people can reclaim their individuality, only through comparison that we notice how people fill a generic form in unique ways.

The Burning Blue (2009) is both the most melancholy and the most mysterious work in the Trilogy. Blue interweaves home-movie footage of various events—geyser eruptions, space shuttle launches—with confounding vignettes reflecting on the nature of collective experience. In one section we are shown, at length, a crowd frozen in anticipation, echoing the denouement of The Eternal Quarter Inch. This is an apperceptive strategy: we identify with the characters in their waiting to the point of becoming aware of ourselves doing so, and waiting with them. Another section of The Burning Blue counterposes screensaver graphics of outer space with a text about a child feigning sickness and missing school, projecting a cosmic loneliness onto the child’s regret about missing an experience with her fellow classmates. By far the strangest part of The Burning Blue is a montage of cities experiencing blackouts. As the bright lights of buildings abruptly cut out, an absence—in this case, of light—becomes the common denominator for thousands of people. Perhaps McLean is saying that the things that bind us together are really the things we all miss out on.

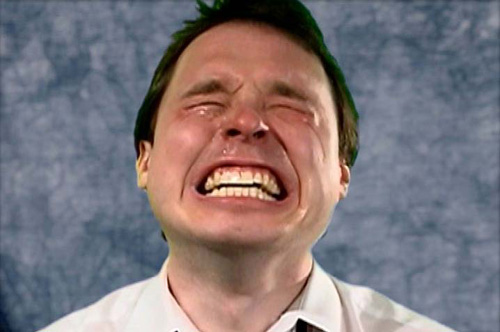

Structured around a series of interviews, Magic for Beginners is simultaneously more unruly and more precise than McLean’s previous works, and also has the strongest narrative velocity. The interviews all explore some experience of fan culture: one woman describes her obsession with Titanic (1997); a man recounts being mesmerized by Tron (1982); another man tells of his trance-like state during a performance by the band Oneida. Aside from the interviews, Magic for Beginners’ two main recurring elements are portrait shots of people making themselves cry and excerpts from Andy Warhol’s book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. The crying is sublimely uncomfortable: contriving the expression of powerful emotions is always darkly comedic, as is made clear in making-of footage from Hollywood melodramas. The thing about these people making themselves cry is that once they’re crying, they’re crying. Forcing yourself to cry is a little bit like forcing yourself to kiss someone: the feeling might be fabricated, but that doesn’t necessarily make the act less real.

The Warhol text leavens Magic for Beginners with some humour, but the natural intricacies of Philosophy also play nicely within the framework of the film. The book’s tension revolves around Warhol trying to convince himself and others that he has no real desires except to consume and waste away. “Once you see emotions from a certain angle,” writes Warhol, “you can never think of them as real again.” The vertiginous irony of Warhol’s text relies on its confounding pathos, buried in the fact that there’s nothing more human than wanting not to want anymore, and convincing yourself that you don’t. With every failure we experience, we censure our desires. What McLean is attuned to is that the perceived failures of popular culture—to be authentic, to be moving, to hold our attention—have resulted in a mass censuring of cultural desire. What the interviews in Magic for Beginners give voice to, and what the film nervously, tentatively asks us to explore, is what happens when we let our wanting get away with us.

The interview about the Oneida concert is followed, much later in the film, by music from the band set to a flicker that gradually increases in rapidity, the boldest moment in Magic for Beginners. Flicker films wreak physiological and psychological havoc in the viewer: because the information being presented cannot be processed in a normal way, you’re forced to let go, materially and philosophically. McLean, then, is strong-arming us, momentarily, into an un-ironic viewing position. Like fake bawling, flicker films contrive a visceral experience that ends up being authentic regardless of its motivation.

Magic for Beginners ends with a montage of many different people singing Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On,” the theme song from Titanic. The strategy of piecing together a pre-existing song using renditions and lip-synchs has become commonplace in found footage moving image work. It’s used in Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby’s Sometimes Numa Numa Makes You Cry (2006), Laric’s 50 50 and Versions of Under the Bridge (2007), Impeto’s Ultimate Canon Rock (2007), Amie Siegel’s My Way 1 and 2 (both 2009), and Dick Whyte’s John Cage – 4’33” [May ’68 Comeback Special RECON] (2010). It no longer carries much weight as a formal gesture, but has become a trope that can be manipulated like any other. Magic for Beginners uses this scene to confront us with something that we would not normally take seriously—Dion’s song is shorthand for everything in popular culture worth Warholizing. But after all the actually discomfiting forced tears and actually disruptive flickers and earnestly recounted fan experiences, we have to ask: who are we to cast our scorn on other people’s love? As Warhol wrote, “Fantasy love is much better than reality love.”

Magic for Beginners screens at the Images Festival in Toronto in the program “On Screen 1: Same Same But Different” on April 1.

Tom McCormack- « Previous

- 1

- 2