Global Discoveries on DVD: Bologna’s Bounty

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

There appears to be a consensus that this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna was exceptionally rich—so much so that I concluded that my next column in these pages could be devoted to some of its riches, most of which are already available on DVD or Blu-ray in one form or another. The most notable exceptions, at least among the newer films shown—Jean-Baptiste Péretié’s 2021 Jacques Tati, Tombé de la lune (not only the best documentary about Tati to date, but the only one to understand the basic fact that Tati essentially wrote his scripts with his body), and Mitra Farahani’s startling À vendredi, Robinson, a staged internet encounter between two nonagenarianNew Wave pioneers, Jean-Luc Godard and Ebrahim Golestan, that encompasses their dialectically contrasting self-portraits—will hopefully become available in the near future, at which point their minor limitations (e.g., Péretié minimalizing the radicalism ofTati’s Parade [1974], Farahani over-maximalizing the radicalism of Godard in her own transgressive editing patterns) can also be discussed.

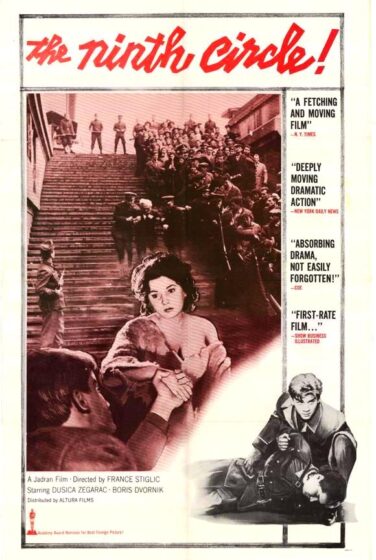

For the others, let me start by noting that two of my favourite Bologna discoveries are both available from Rarefilmsandmore.com for $13.99 US apiece: France Štiglic’s 1960 The Ninth Circle (shown in Mina Radović’s excellent Yugoslav program) and Alexis Granowsky’s 1931 The Trunks of Mr. O.F. (which screened in Alexander Horwath’s no less discerning Peter Lorre retrospective). Reportedly the first Yugoslav feature ever nominated for an Oscar, though seemingly cut by about five minutes in most circulating copies (including the Rarefilms version), The Ninth Circle is the most powerful and gripping fiction feature about the Jewish Holocaust that I’ve seen, written by a Jewish woman (Zagreb-based Zora Dirnbach) who lived through it and easily justifying all its melodramatic punctuations, including its Dante-derived title. The film recounts the experience of a young Jewish college student who gets hastily married to a non-Jewish classmate in a friendly family after seeing her own family shipped off to the death camps, and then remains cloistered in the family’s apartment for fear of being recognized by Croatian police on the city’s streets. Many other plot complications follow—including the fake married couple falling in love with one another—and the narrative momentum is brilliantly sustained.

The Trunks of Mr. O.F, a consistently inventive and hilarious satirical farce that suggests an early René Clair talkie in German, features a chubby, M-era Peter Lorre, before he went to England and worked for Hitchcock, but it’s the script and direction more than the star that impressed me the most. A Depression comedy that charts the economic boom overtaking a nondescript German village after 13 trunks for a future guest arrives at its only inn, which quickly transforms itself into a luxury hotel, this has the sort of quirky, acerbic wit and originality that one finds in many of the best early talkies, making it a musical in spirit if not in fact. (Another Bologna program, and one that I lamentably missed entirely, was in fact devoted to early German musicals.)

For a superb Lorre performance—the subtlest and most nuanced of his that I’ve recalled seeing, in contrast to his memorable histrionics in M (1931)—I can recommend Robert Florey’s The Face Behind the Mask (1941), available both on DVD and on a much pricier Blu-ray. Lorre must have regarded his role here as a rare technical challenge: he plays an immigrant to the US whose face, hideously mutilated by fire, is mostly hidden behind a form-fitting mask. How Lorre meets that challenge is every bit as awesome as what Charles Laughton does with his eponymous character in Robert Siodmak’s 1944 The Suspect (available on an affordable Blu-ray), which was justly praised by Simon Callow (in his fine biography of the actor) for Laughton’s performative inflections. Admittedly, Siodmak is a much better director than Florey, but for someone like me who defines the art of cinema as something that isn’t necessarily restricted tomise en scène, The Face Behind the Mask is a revelation. (It had the same effect on film scholar Noa Steimatsky, who told me she wished she’d seen it before writing her 2017 book The Face on Film.)

On the other hand, the wonderful Hugo Fregonese retrospective put together by Dave Kehr and Ehsan Khoshbakht at Il Cinema Ritrovato reawakened and satisfied all my auteurist reflexes. This wasn’t only because the first two Fregonese films I saw in Bologna for the first time: One-Way Street (alas, unavailable) and Saddle Tramp (available on a PAL Italian DVD, as Vagabondo a Cavallo), both from 1950, which tell two versions of the same story in separate genres (the former a globetrotting noir with James Mason, the latter an especially fetching Western with Joel McCrea and evocations of Mark Twain’s Huck and Tom). It was also because the thematic continuity traced by Kehr—an existential treatment of destiny and the consequences of decisions—can be found not only in those two films, as well as in the exciting visuals of Fregonese’s 1951 Val Lewton Western Apache Drums (misdescribed by Manny Farber as the “least” of the Lewton–produced features, a judgment that would be more aptly assigned to the 1944 films Mademoiselle Fifi or Youth Runs Wild), but also in Seven Thunders (1957, available on DVD) and especially in my favourite in the bunch that I saw: The Raid (1954), a Van Heflin Civil War Western with Lee Marvin as one of the heavies, available on a 20th Century Fox Cinema Archives DVD. For the record, though, the favourite among most of the other Fregonese-watchers I spoke with was the extravagant, almost operatic 1954 Edgar G. Robinson gangster pic Black Tuesday (1954, available on DVD but only in a lousy print), but I agreed with Erika Balsom’s observation that pure good and pure evil don’t generally yield interesting characters or stories, at least not in relation to the real world.

A screening of a restored early Carl Dreyer feature, Love One Another (1922), in Mariann Lewinsky and Karl Wratschko’s 1922 program (with a superb piano and harp accompaniment) afforded me my first look at the film where I could both follow the extremely complicated plot and appreciate what was most Dreyeresque about it, such as its historical authenticity as well as its political incorrectness regarding both the Russian Revolution and the persecution of Jews. (Intolerance here isn’t the exclusive property of non-Jews and non-revolutionaries.) This version was scanned from the original nitrate print discovered in 2005 with the help of Bernard Eisenschitz (for those who can follow unsubtitled French, Eisenschitz’s impressive lecture on Dreyer at the Cinémathèque française is available at vimeo.com/191944028). The Danish Film Archive released an earlier and shorter restoration some time ago, along with Dreyer’s The Bride of Glomdal (1926), on a PAL Blu-ray for $40, but I hope this more comprehensive version will also become more widely available, ideally with same piano-and-harp score. (However, given Criterion’s recent addiction to political correctness—which has already ruled out both Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind [2018] and Abbas Kiarostami’s 10 [2002] as possible releases—I suspect it may have to be on another label.)

The Museum of Modern Art’s recent restoration of Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives (1922), shown in Bologna’s Piazza with a full orchestral score, doesn’t qualify as a “discovery” for me in the same way as Love One Another (apart from the effective uses of colour in the film’s climactic fire), because I’m still sorting out what I think of this new version and how it compares to the earlier version assembled by Arthur Lenning that’s available on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray. Obviously, I’ll have to see it again, and another digital release would clearly facilitate this. Meanwhile, I continue to regard Stroheim’s performance in every version of Foolish Wives that I’ve seen as his most definitive and fascinating achievement as an actor—above all in his “hiding in plain sight” (like Poe’s purloined letter) as an imposter playing an imposter, thereby demonstrating that Stroheim, like Welles, was his own harshest critic.

This leads me to cite another discovery I made in Bologna, albeit a relatively minor one: Gregory Ratoff’s 1940 I Was an Adventuress (available on a pricey Blu-ray), starring Vera Zorina in the title role, and co-starring Stroheim and Peter Lorre as her accomplices. (This diverting romp was shown as part of the Lorre retrospective.) Reportedly, the two of them were friends in real life; on the evidence of this film, they certainly knew how to play well together.

P.S. Although I haven’t yet seen Execution in Autumn (1972), directed by Lee Hsing (who died last year at age 91), I can nevertheless recommend the Masters of Cinema Blu-ray of the film to readers with region B players for the huge historical contribution of Tony Rayns’ exhaustive 44-minute introduction, which explains in detail why this Confucian melodrama illustrates the transition between what Rayns describes as the “wasteland” of earlier Taiwanese cinema and the subsequent New Wave of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, Tsai Ming-liang, and others. It’s the sort of cross-referential, in-depth analysis that I haven’t encountered elsewhere, either in print or on other digital releases.

Jonathan Rosenbaum