Global Discoveries on DVD: Bologna Awards and Mixed & Unmixed Blessings

By Jonathan Rosenbaum.

I

Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Lucien Logette, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. Chaired by Paolo Mereghetti.

PERSONAL CHOICES

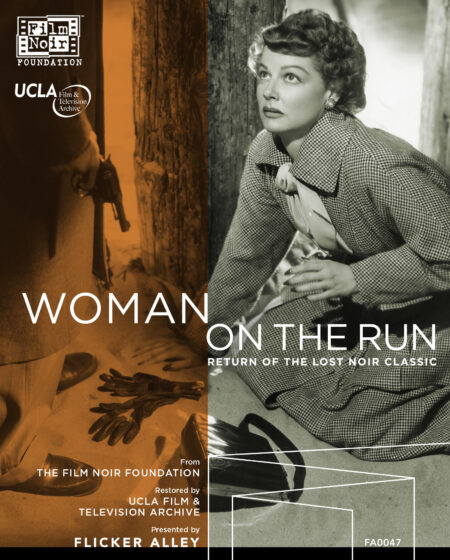

Lorenzo Codelli: Norman Foster’s Woman on the Run (1950, Flicker Alley, Blu-ray). A lost gem rescued by detective Eddie Muller’s indefatigable Film Noir Foundation.

Alexander Horwath: Déja s’envolé la fleur maigre (Paul Meyer, 1960, Cinematek/Bruxelles, DVD) and Il Cinema di Pietro Marcello: Memoria dell’immagine (2007-2015, Cinema Libero/Cineteca di Bologna, DVD). Regarding the latter: with this cinematheque-style DVD, subtitled in English and French, one of the greatest contemporary filmmakers, whose work is still underappreciated outside Italy, receives his rightful chance for global recognition.

Lucien Logette: Tonka Šibenice (Karel Anton, 1930, Czech Republic, Národní filmový archiv/Filmexport Home Video, DVD). One of the first Czech sound films. Like many great films of that era, it reflects several influences: Expressionism, social realism, Kammerspielfilm, the art of Soviet photography, all used remarkably, without imitation. It contains all the great themes of the end of the silent period: the opposition between the city and the countryside, the misdeeds of modern society, frustrated loves ending in drama, themes served by an astonishing visual beauty.

Mark McElhatten: Kafka Goes to the Cinema (Munich, four-DVD box set, Edition Filmmuseum). All of the films extant that Kafka saw in cinemas and referred to in his writings are included in this set. The films range from a Mary Pickford feature to Danish and French silent dramas, documentaries from Russia and Palestine and more. A poetic concept with a factual basis yields a fascinating collection of films from seven international archives. An unimaginable miscellany made coherent through an inspired premise.

Jonathan Rosenbaum: Two profound last features by great writer-directors, Josef von Sternberg’s Anatahan (1953, Kino Lorber, DVD & Blu-ray) and Robert Bresson’s L’Argent (1983, Criterion, DVD & Blu-ray), both released too recently to qualify as nominees. The former makes a perfect complement to Sternberg’s first feature, and the latter has two especially valuable extras: an audiovisual essay by James Quandt and Bresson’s astonishing trailer, less than half a minute long (and the best “new” film I’ve seen so far this year).

BEST BONUS FEATURES

Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974, Arrow Films, Limited Edition Blu-ray). The curators of this splendid 4K restoration literally managed to bring us the head of Sam Peckinpah, along with those of the Wild Bunch of his collaborators. Since it’s impossible to list all of the special bonuses included, let’s propose a theoretical equivalent: biographer Paul Joyce offering the ten-hour-long, uncut version of the interviews for his documentary Sam Peckinpah—Man of Iron. (Lorenzo Codelli)

A SPECIAL PRIZE FOR TWO UNWIELDY RELEASES

Wajda (Poland, 1954-2013, Cyfrowe Repozytorium Filmowe [Digital Film Repository], DVD) and Robert Frank: Film Works (USA, 1959-1975, Steidl, DVD). Formidable retrospective collections devoted to directors and designed as unique objects. Both of these items, like the earlier Murnau, Borzage and Fox, are impossible to shelve with other DVDs, and are seemingly targeted at individuals who own no other DVDs. Wajda comes with a book featuring Andrzej Wajda’s account of his career and offers itself as a nationalist monument. The more eclectic assembly of Robert Frank’s films comes in what resembles a lunchbox, includes a book of critical essays (including one by me, which is why I recused myself from voting for this) and both PAL and NTSC versions of every film. Unfortunately both Cocksucker Blues and Candy Mountain are omitted. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

BEST BOX SET

Pioneers of African-American Cinema (USA, 1915-1944, Kino Lorber, Blu-ray) and Dekalog (Poland, 1985, Arrow Films, DVD & Blu-ray) are both exemplary instances of the way in which a box set can shed light on a whole chapter of film history.

The five-disc Pioneers gives us deep insight into the fascinating era of the so-called “race-cinema circuit” in the US from 1915 to the mid-’40s, with more than 20 works from black filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux, Spencer Williams, and many more unknown ones, including discoveries like The Flying Ace (1926) and Hell-Bound Train (circa 1930). The 75-page booklet with a magnificent essay by Charles Musser is an important part of this rich collection.

Dekalog, published in both DVD and Blu-ray versions, is not only a complete representation of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s famous TV project in wonderful restorations from Telewizja Polska, but also includes his other, much lesser-known films for television. The box thus shows that he was at least as much a master of the “home medium” as of the cinema. As with Pioneers, the beautiful little book that comes with the box is highly welcome, with the texts mostly by Kieslowski himself. (Alexander Horwath)

BEST DVD

Colour Box: 19 Films by Len Lye (USA/New Zealand, 1929-1980, Len Lye Foundation/Govett-Bewster Art Gallery/Ngã Taonga Sound and Vision, DVD). Poet, philosopher, inventor, and total artist Len Lye was a personality as exuberant and colourful as his films: he was a coalman on a steamer, a postal worker, an adopted member of a Maori tribal community, a lecturer in New York. Lye was a pioneer of kinetic sculpture (“Tangibles”), direct drawing, and painting on film. Most of Lye’s commercial public service commissions were as wildly imaginative as his personal projects. He was a mentor to Jack Smith (another one of the greatest colourists of cinema) and an influence on Stan Brakhage and many younger experimental filmmakers of our present century. His amazing work had key periods of exposure, but then became unseen, if not forgotten. Fortunately, in the last few years there have been some fine exhibitions and publications devoted to Lye. Most essential is this DVD issued by the Len Lye Foundation of New Zealand that includes 19 films from 1929 to 1979. Our DVD of the year. (Mark McElhatten)

PETER VON BAGH AWARD

The Salvation Hunters (1925, Austria, Edition Filmmuseum, DVD). Josef von Sternberg’s first feature, beautifully presented, with two precious extras: an audiovisual essay by Janet Bergstrom, and a dazzling four-minute fragment from Sternberg’s The Case of Lena Smith (1929). Alexander Horwath, who worked on this release, refrained from voting for it for that reason. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

II

1. Let me start with what I regard as a perfect illustration of the mixed blessing that DVDs and Blu-rays sometimes offer. First, a wonderful discovery offered on Disc One of The Twilight Zone: The Definitive Edition—Season 5, a box set that I once purchased simply because I have a periodic (if totally impractical) desire to regard myself as a Jacques Tourneur completist, and wanted a copy of his episode “Night Call.” But an unexpected side benefit of this questionable trait is Episode #125 (originally aired on October 25, 1963), “The Last Night of a Jockey,” which boasts Mickey Rooney as its only actor. Rod Serling’s formulaic introduction is typically self-righteous in its stupidity and typically stupid in its self-righteousness, and the premise is built around an odious ex-jockey banned from horse racing who’s granted his wish to become over eight feet tall, which becomes his comeuppance and allows for some special effects via set design that is the story’s sole point of interest. But the performance of Rooney as an obnoxious pipsqueak is downright spectacular—almost as impressive as his equally unsympathetic playing of the eponymous lead in The Comedian on Playhouse 90 in 1957 (another Serling script, this time adapting an Ernest Lehman novella), which I think might be John Frankenheimer’s most dazzling work in live television; it’s available on Criterion’s The Golden Age of Television.

So much for the unmixed blessing of Rooney’s extraordinary acting, which speaks for itself. But unfortunately, someone who worked on this Twilight Zone box set decided that we all needed an audio commentary from Rooney about this, and one was duly recorded, during which Rooney has absolutely nothing to say about either this episode or his performance in it. One certainly can’t blame him for this: delivering such a performance is already an amazing accomplishment, and it seems sinful to require him to answer a string of inane and pointless questions about it years later, which he dutifully tries and fails to do. All of which adds up to a certain amount of unnecessary torture for both Rooney and whoever winds up listening. So Serling’s formulaic pretense about delivering a fable with a moral as a dopey excuse for Rooney’s powerful performance winds up getting matched by the equally formulaic pretense of offering an empty DVD extra.

2. I’ve always liked François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966); along with La chambre verte (1978), it’s probably my favourite of his underrated colour films. Thanks to Universal’s 50th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray, its melancholy poetry looks and sounds better than ever. Without ever being in the least bit imitative, it’s surely the closest Truffaut ever got in his films to Godard, in terms of visuals (the reds here are even more vivid than those in Made in USA, which was released the same year, and sometimes the editing is comparably eclectic) as well as literary references. But I have two objections to the otherwise excellent extras on the Blu-ray, one major and one minor. The major one is that apparently no one thought to reprint Truffaut’s wonderfully lively and thoughtful diary of the film’s shooting—one of his major texts, serialized at the time in Cahiers du Cinéma (and, as far as I know, apart from its subsequent appearance in Cahiers du Cinéma in English, unavailable in English translation ever since). And my minor complaint, which applies to both the audio commentary and the documentary about the film’s production, is the claim that the film isn’t science fiction—which largely comes from Annette Insdorf, who seems to equate science fiction with special effects and fancy sets while ignoring that it can also be social satire and social commentary, which Truffaut’s film plainly is. The film isn’t as political as Godard’s Alphaville (1965), though it still has a lot to say about the way people live.

It’s quite possible that what confuses the issue for many people is that the film belongs to the French generic category of fantastique (as does Alphaville, for that matter), with a much looser and freer relation to science and to probability than is usually associated with Anglo-American science fiction; Cyril Cusack finding a microscopically tiny book in a baby buggy and then chastising the infant for it is a perfect example of what I mean, and one could cite several other deliciously off-the-wall conceits (such as the firemen’s practice of sliding up as well as down their poles). In any case, it’s an interesting contrast between national perspectives that Julie Christie (on the audio commentary) is fully alert to the film’s social critique, while both the American producer and Insdorf tend to slide past it. On the other hand, I suppose one could also argue that the craziest, most off-the-wall conceit in the film comes from the Ray Bradbury novella: the fact that all the characters know how to read, which they obviously learned how to do at some point, even though they’re forbidden to have any books.

3. The Ruscico DVD of Sergey Paradzhanov’s The Shadows of the Forgotten Ancestors (their spelling and title) includes, among other reverential extras, a fascinating short about the friendship and spiritual and aesthetic compatibilities of Paradzhanov and Andrei Tarkovsky. And what makes this a mixed blessing? Try navigating Ruscico’s intractable website sometimes (www.ruscico.com); you might have slightly better luck ordering their DVDs from a German site (www.petershop.com).

4. Tired of hearing about Truffaut on Hitchcock and interested in hearing about Chabrol on Hitchcock for a change? Check out the new Italian DVD of Hitchcock’s Under Capricorn (1949), known as Il Peccato di Lady Considine, and you’ll see that the principal extra is a half-hour, anecdotal French interview with Chabrol conducted in 1999, focusing on such matters as Cahiers du Cinéma’s special Hitchcock issue in the 1950s and Chabrol and Rohmer’s book on Hitchcock (the first in any language). But the only subtitles are in Italian.

III

A few unmixed blessings: (1) Criterion’s superb and beautifully designed Blu-ray of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979); among the valuable extras are an interview with Geoff Dyer that, for me, surpasses his book about the film. (2) I haven’t bought or looked at the North American Blu-ray of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin (2015), but the French-subtitled version that I picked up in Paris, which seems roughly comparable in terms of its extras and its affordable price, is gorgeous. (3) At Il Cinema Ritrovato, I managed to miss Robert Parrish’s The Wonderful Country (1959) in the Robert Mitchum retrospective—according to co-programmer Philippe Garnier, Mitchum’s best Western—but the French Blu-ray I picked up just afterwards in Paris, under the title L’Aventurier du Rio Grande, with lengthy intros by Bertrand Tavernier and Patrick Brion and a short documentary about Mitchum by Jean-Claude Missiaen (all in unsubtitled French), is also reasonably priced.

(4) If you’ve never seen King Vidor’s 1931 film of Elmer Rice’s Street Scene—which Andrew Sarris once described to me as “pre-Bazinian” after we both saw it at the Cinémathèque française—you should. Rice, adapting his own play, places all the action in front of the same tenement building, making the most of windows, front stoop, sidewalk, and street, but Vidor’s filming of the action is fluid and mobile, anything but stagey. I haven’t seen the $7.99 DVD available on US Amazon—which I only learned about after purchasing the version released by Lobster Films in a Paris bargain bin—but the French version is watchable. (5) Peter Tscherkassky’s well-titled Exquisite Ecstasies, a new DVD on Austria’s Index label, combines the 19-minute The Exquisite Corpus (2015)—a deliciously sensual exercise in reconstructed (as opposed to deconstructed) porn, which Daniel Kasman wrote about in Cinema Scope 63—with four of the filmmaker’s shorter and earlier experiments from the ’80s, all paving the way towards this apotheosis (as Tscherkassky himself explains, in the accompanying 24-page bilingual booklet).

(6) For someone like me who’s still gradually recovering from a lifetime of Disney brainwashing about how to crossbreed animation and live-action, all of which has kept me from encountering the special brilliance of Czech fantasist Karel Zeman, Second Run’s multifaceted, multi-region Blu-ray of The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1961) is a treasure chest of enlightenment about his life, career, studio, and intricate methodologies. Quite apart from the feature itself, which combines animation with live-action in personal and ingenious ways that the Disney folk have never dreamed about, with heavy doses of both Jules Verne and Gustave Doré, there’s a fascinating feature-length documentary, Film Adventurer Karl Zeman (2015), and no less than eight shorts featuring mostly highlights from the documentary, including reverential soundbites from Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam—though not, alas, Wes Anderson, another Zeman acolyte. (7) You can order a pretty good copy of Louis [sic] Buñuel’s greatest and most terrifying Mexican feature, Los Olvidados (1950), from US Amazon for just slightly over $5.

Jonathan Rosenbaum