Global Discoveries on DVD: Criticism vs. Fan Fodder

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

As a lifelong film buff who became a professional film critic in my late twenties, I’ve spent much of my life ever since trying to reconcile these two distinct and, in some respects, conflicting identities. Many of my colleagues seem to regard criticism and fandom as reverse sides of the same commercial coin—compatible and mutually reinforcing facets of the same impulses, sometimes blissfully fusing into a sincere form of advertising. (A perfect example of this in action is Andrew Sarris’ rapturous and well-informed two-part review of Resnais’ Muriel [1963], which has recently become my favourite piece of Sarris prose, thinking and feeling with equal amounts of passion.)

For me they’re periodically in conflict with one another, philosophically and aesthetically. Giving a mixed review to Gjon Mili’s Jammin’ the Blues in 1944, James Agee seems to have felt this way about his former taste as an indiscriminate jazz buff, maintaining that the short “is too full of the hot, moist, boozy breath of the unqualified jazz addict, of which I once had more than enough in my own mouth…”

Although we often overlook the religious piety and the reverence (arguably another form of addiction) that accompanied the politique des auteurs as it developed in France in the ’50s, the degree to which it was informed by such protocols is difficult to deny. I’ve often suspected that a taste for the low camera angles in Welles’ early pictures might have had something to do with kneeling and praying; and the fact that Hitchcock, a fellow Catholic, was a deity to many of the Young Turks at Cahiers du Cinéma suggests that the reverence that comes with fandom has a certain tinge of religiosity. Similarly, the fan base that keeps Donald Trump afloat is still strong or at least vocal enough to worry his critics.

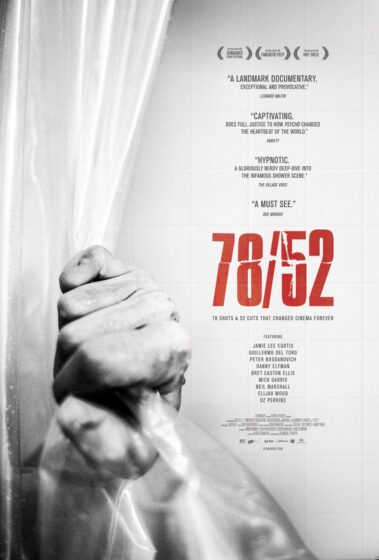

My recent and belated discovery of some of the documentaries of Alexandre O. Philippe—The People vs. George Lucas (2010); Doc of the Dead (2014), on George Romero’s zombie pictures; 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene, devoted exclusively to the shower murder sequence in Psycho (1960); Leap of Faith: William Friedkin on The Exorcist (2019); Existential Zombies: Antonioni’s L’eclisse, a 2019 DVD extra; Lynch/Oz (2022), examining diverse links between David Lynch and The Wizard of Oz (1939); and The Taking (2021), about the uses of Monument Valley in Western)—has shown me how the separate self-definitions of critics and buffs can sometimes wind up at cross-purposes, and why we don’t distinguish fandom from criticism as often or as carefully as we should.

All the Philippe works I’ve seen combine some fandom with some criticism, but the proportions between the two are never the same. Sometimes, as with the films about Monument Valley and L’eclisse (1962), sharp criticism wins out; when it comes to Lucas, Friedkin, and Hitchcock, devoted fandom dominates, virtually ruling out any moral reckonings for either the bloodbaths/mudbaths of Psycho or the bloodless, mudless, and implicitly celebratory slaughters of Star Wars (1977),whose creator Lucas seems to have taken over from Disney as the great paternal comforter who runs his own role-model factory for slightly older kids.

None of the seven Philippe documentaries I saw is as nihilistic as Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 (2012), which treats serious critics of The Shining (1980) and semi-crazed Kubrick fans, including conspiracy theorists, with equal amounts of credence and respect. But most of them pitch their tent inside fandom rather than at some critical distance away from it. The most glaring exception to this tendency is The Taking, a highly critical, conscientious, and revealing look at mythologizing in the movies of John Ford and other Westerns—most particularly their theft of Monument Valley from Native Americans—that got me to look at the other Philippe documentaries. This is the most useful Ford criticism I’ve encountered in some time, along with Throwing in John Ford’s Movies (a video of clips, accessible at vimeo.com/785390541, password: doctorbull, put together at Tokyo University to illustrate Hasumi Shigehiko’s brilliant essay on the subject at www.rouge.com.au/7/ford.html), or Joseph McBride’s remarks in his book Searching for John Ford about how the critique of racism against Black men in Sergeant Rutledge (1960) is effectively fuelled and spiked by its treatment of Native Americans as subhuman warrior savages, like those in Ford’s earlier Drums Along the Mohawk (1939).

To single out one of the New Wavers, I would argue that Jacques Rivette eventually went from being both a fan and a critic to being mostly just a fan when he spoke about films in interviews. If you consult the chronological arrangement of interviews collected by James R. Russo in Jacques Rivette and French New Wave Cinema, there’s a clear drop after the mid-’70s corresponding to Rivette’s gradual retreat from being a trailblazer as a filmmaker to being a journeyman director who goes on playing the same formal and thematic games, albeit more conservatively and cautiously (as reflected in his eventual deletion of Jean-Pierre Léaud’s violent mad scene near the end of Out 1 [1971]). In the interview of Rivette by Frédéric Bonnaud in Les Inrockuptibles in 1998, the filmmaker’s cranky comments periodically evoked for me former New York mayor Ed Koch during his brief stint as an off-the-cuff film reviewer. This is a far cry from Rivette’s 1959 exchanges with Godard (also in the Russo volume) about Hiroshima, mon amour (1959)inrelation to Faulkner, Stravinsky, Eisenstein, Renoir, and Resnais’ earlier Toute la mémoire du monde (1956).

Furthermore, writing as an old-fashioned cinephile and critic who formed most of my filmgoing habits in pre-digital situations, I like to associate many of my activities with DVDs, Blu-rays, and streaming as forms of reviewing (in both senses of that term) films that I previously discovered in analog form—a predisposition that admittedly makes the very title of this column sound deceitful. This offers a concrete example of the ongoing struggle between my reflexes as a fan and my reflexes as a critic.

As Agee suggested, the logical and inevitable result of fandom is addiction, a malady that makes all its victims seem boringly identical, as The People vs. George Lucas makes abundantly clear. Philippe’s documentary oscillates between being a report on fandom/addiction and a symptomatic expression of both, until these seeming alternatives fuse into a synthesis. Infantile, a commentary on being infantile, and/or both at once—and does it really matter which? (Infantilism is the common curse of our technology’s capacity for instant gratification, so isn’t it possible to view the recent mass shootings as tantrums?) As in William Klein’s The Little Richard Story (1980), which is top-heavy with Little Richard impersonators—welcomed into the documentary after its title subject decided to exit in midstream—it’s hard (and perhaps unnecessary) to separate the real George Lucas here from the diverse simulacra produced by his fans, making him a shared concept more than a physical being. And the desire of fans to become part of the Star Wars spectacle while continuing to be spectators marks them as active narcissists akin to the Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) cultists, not to mention the Imperial heroes/ destroyers who cheerfully equate the bloodless deaths they score with points won in a video game.

Friedkin’s reflections on some of the impulses that fed into The Exorcist (1973) have a journalistic value even when they seem misguided—e.g., his claim to have been influenced by Dreyer’s Ordet (1955), which he ludicrously describes as “simple,” suggesting he may not have even noticed the subtle complexity of the camera’s 360-degree rotation around a dialogue between two characters who continue to face the camera throughout (in contrast to, say, the blunt simplicity of the 360-degree rotation of Regan’s head in The Exorcist). 78/52 is another case of criticism competing with and then losing out to fandom, largely because Philippe doesn’t appear to regard Psycho’s violence (as he regards John Ford’s Monument Valley) as something with ethical and ideological significance—the cynical way that Hitchcock regarded the whole movie as a prank or joke goes unexamined. The audience of Psycho is presumed to be innocent, while that of the Ford Westerns is implicitly shown as passively corrupted by the various historical concealments and distortions.

Psycho has never been one of my favourite Hitchcock pictures. The first time I saw it, during its initial release in 1960, I’d already read the Robert Bloch novel it’s based on, a fairly routine horror thriller, so the surprise ending was anything but surprising to me. I saw the movie back-to- back with Let’s Make Love, which I liked a lot more: Yves Montand spoke English awkwardly, but Marilyn Monroe was irresistible—for practically the only time in her career, she played a character who was both smart and feisty. In Psycho, Janet Leigh, who I also had a crush on at the time, was pretty feisty as well, but after she got knifed to death in the shower early on there was only drab Vera Miles to contend with, not to mention additional gore, cumbersome exposition, John Gavin, and reams of psychobabble about Norman Bates that I could never fully swallow (or even entirely follow).

Psycho placed second among the box-office winners of 1960, after Ben-Hur; Let’s Make Love didn’t even make it into the top 20. The critical fates of the two pictures have been similarly disparate: for many people, Psycho remains Hitchcock’s greatest picture and one of the greatest Hollywood movies ever made, but even most aficionados of director George Cukor wouldn’t call Let’s Make Love one of his dozen best pictures. Now that many critics, including me, regard Hitchcock as one of the key artists of cinema—which wasn’t the case in 1960, even for most French critics—I can readily concede the error of my judgment at the time. But that doesn’t mean Psycho has ever captured my heart the way Let’s Make Love once did.

Today, despite some of its ugly and indifferent patches (almost everything involving Vera Miles, John Gavin, and, above all, the psychiatrist played by Simon Oakland), I find Psycho a film of corrosive brilliance, one that works on my mind and nerves more than on my feelings. This may be in part because, by now, the shower stabbing has become the most drooled-over sequence in the history of cinema. Whatever my ideological and visceral misgivings about the Odessa Steps sequence in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925)—which has been fetishized almost as much as the Psycho scene—I can’t accuse it of spawning a cottage industry in gleeful onscreen lady-carving as Hitchcock’s piece of bravura did. But let me be just: the first 53 minutes of Psycho—very nearly the first half, everything from when we enter a seedy Phoenix hotel room to when we see the sinking of a car in a marsh, capped by Norman Bates’ triumphant grin—constitute one of the supreme achievements of Hitchcock’s career. What makes it so remarkable is not simply the hysteria provoked by the repressed sexuality, but the no less troubled feelings it arouses about money—too little money, too much money, money as a signifier of despair and twisted human impulses. Indeed, it’s the interplay between sex and money (as ferocious here as it is in Charlie Chaplin’s no less misogynistic/misanthropic Monsieur Verdoux [1947]) that accounts for the extraordinary sense of dread that infuses these 53 minutes—an interplay of perpetual displacement and substitution that culminates in the simultaneous descent into slime of both the sex object and the $40,000 she stole. The crime of murder both effaces and permanently conceals the crime of theft around the same time that our moral position shifts from being complicit in an act of spontaneous theft to being complicit in an act of spontaneous murder. Yet as far as 78/52 is concerned, it’s virtuoso filmmaking whose interest is mostly formal.

***

Postscript: Marcel When’s 2007 One Who Set Forth—Wim Wenders’ Early Years, available on Amazon on an inexpensive DVD and on streaming from Ovid.tv (where it’s called Wim Wenders’ Story of His Early Years), is critically and biographically useful in various ways (such as the information that Wenders underwent extensive psychoanalysis as a teenager), but it’s aimed mostly at fans rather than the sort of viewers who wouldn’t instantly recognize Bruno Ganz the moment he appears. It’s a pity that the subtitler didn’t know French well enough to identify the phrases “Nouvelle Vague” and “Deux Magots” when they’re spoken, and didn’t seem to know that the English title of Wenders’ 1976 film Im Lauf der Zeit is Kings of the Road, not In the Course of Time. But, of course, you can’t have everything.

Jonathan Rosenbaum