Global Discoveries on DVD: Second Thoughts & Double Takes

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

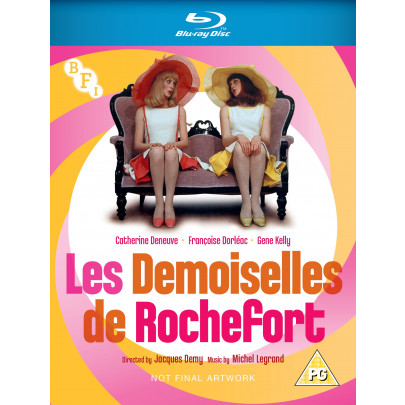

On “A Melody Composed by Chance…”—an excellent new audiovisual analysis of Jacques Demy’s Les demoiselles de Rochefort (1967) on the BFI’s Blu-ray of the film, written and narrated by Geoff Andrew and deftly edited by this disc’s producer Upekha Bandaranayake—I’m grateful to Andrew for correcting the gaffe in my booklet essay claiming that the film’s offscreen ax-murder victim is the Lola (Anouk Aimée) of Demy’s first feature, who subsequently turns up in Model Shop (1969); in fact, it’s the much older Lola Lola of The Blue Angel (1930), Josef von Sternberg’s first Marlene Dietrich feature. The other notable extras on this release include “feature-length” audio interviews with Demy (by Don Allen), Michel Legrand (by David Meeker), and Gene Kelly (by John Russell Taylor), Agnès Varda’s essential documentary Les demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993), and a fact-filled, critically acute audio commentary by Little White Lies’ David Jenkins—I especially like the way Jenkins cross-references this film with Varda’s underrated Le bonheur (1965), another film that posits dark ironies behind the Hollywoodish dreams it celebrates.

***

I find it astonishing, really jaw-dropping, that Midge Costin’s mainly enjoyable Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (2019), available on a UK DVD on the Dogwoof label, can seemingly base much of its film history around a ridiculous falsehood: the notion that stereophonic, multi-track cinema was invented in the ’70s by the Movie Brats—basically Walter Murch, in concert with his chums George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola—finally allowing the film industry to raise itself technically and aesthetically to the level already attained by The Beatles in music recording. I’m as much of a Murch fan as anyone, but attributing the invention of stereophonic movie sound to him is an outlandish stretch, overlooking both the stereo sound used by Walt Disney in some of the theatres showing Fantasia (1940) and the multi-track speakers used in hundreds of other theatres across the US throughout much of the ’50s for films screening in CinemaScope, Cinerama, and Todd-AO. By pretending that none of this ever happened or existed, as Costin seems to do, we wind up in a far more impoverished version of the present than we have to be.

***

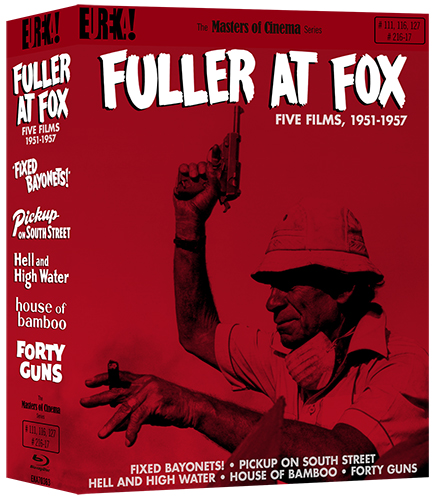

In keeping with this short-changed version of movie history, Eureka!/Masters of Cinema’s Blu-ray box set Fuller at Fox: Five Films 1951-1957—encompassing Fixed Bayonets (1951), Pickup on South Street (1953), Hell and High Water (1954), House of Bamboo (1955), and Forty Guns (1957)—boasts “original, uncompressed, monaural soundtracks for all films.” The last three of these films are in CinemaScope, and according to Wikipedia—for my money, a more dependable source for film information than the Internet Movie Database (see below), perhaps because it’s run by people who care more about facts than about rules and formulae—Twentieth Century-Fox’s CinemaScope “used up to four separate magnetic sound tracks” until around 1957 (at least for theatres equipped to show films that way), and mono tracks for other theatres. I’m less sure about House of Bamboo and Forty Guns, but if my still-vivid aural memories of screenings at the Shoals in Florence, Alabama are reliable, Hell and High Water was seen, heard, and shown there in stereo, as were dozens of other Fox films in CinemaScope—at least the first three dozen or so, which included Hell and High Water. Having expressed my quibble about the sound, let me hasten to add that among the many welcome extras in this bounteous collection is a 100-page illustrated book with contributions by Fuller (one devoted to each picture), Richard Combs, Jean-Luc Godard, Murielle Joudet (two essays), Philip Kemp, Glenn Kenny, and Amy Simmons.

***

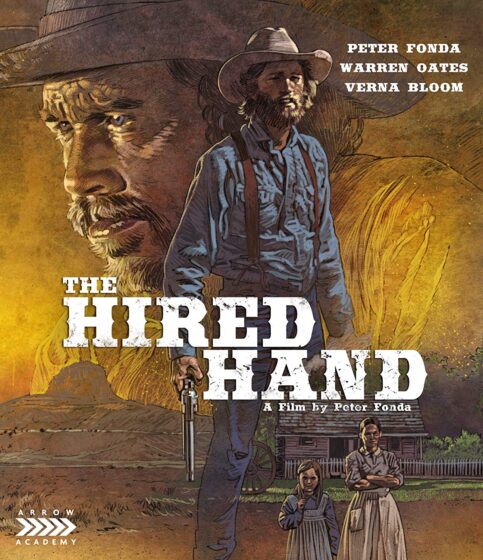

Considering all the time I’ve wasted trying to make some kind of sense out of Dennis Hopper (1936-2010), I missed the boat when it came to considering the career of Peter Fonda (1940-2019) until his recent death, combined with a tip from Nicole Brenez, got me to catch up very belatedly with his Western The Hired Hand (1971), which is arguably more interesting and inventive than anything ever directed by Hopper, with the possible exception of Out of the Blue (1980). My own version of the “collector’s edition” of Fonda’s first feature is Tartan’s two-disc DVD package, but to all appearances, the Sundance Channel’s single-disc DVD and Blu-ray have the same extras (deleted scenes, making-of documentary, Martin Scorsese intro, and Fonda audio commentary). Let’s also not forget that Fonda was possibly the individual most responsible for getting Easy Rider (1969) made, which makes the relative obscurity of his own directorial career even more unfortunate.

***

Most of the time, I’m proud to be a member of the National Society of Film Critics, an organization that can be joined only if one is nominated by another member and then voted in by enough members after sample reviews are submitted. One of the few times I wasn’t proud was when I nominated the late, great Ronnie Scheib (1944-2015) after she became a reviewer for Variety, and she was then voted out of the NSFC, not in. I still don’t know why this happened: perhaps it could have been because she was a woman, or because she wrote for Variety (unlikely, because many other women and Variety reviewers got voted in), or simply because a lot of members didn’t like her reviews. This also seems unlikely, because she was a good writer and a skillful critic, as well as the only practicing female disciple of Manny Farber that I’m aware of (although this was understandably less apparent in her Variety reviews); but insofar as Farber himself had been a former NSFC member, and reportedly an argumentative and disgruntled one, maybe this association worked against her.

Years later, you can join me in being dumbfounded by this injustice if you pick up Kino Lorber’s essential Blu-ray box set Ida Lupino: Filmmaker Collection—which includes Not Wanted (1949), Never Fear (1949), The Hitch-Hiker (1953), and The Bigamist (1953)—and read Ronnie’s lengthy, definitive 1973 essay “Ida Lupino: Auteuress,” which consumes all but about four pages of the set’s accompanying illustrated booklet; those remaining pages are devoted to a bio of Scheib by Justin Chang, another Variety reviewer who later got voted into the NSFC and is the organization’s current chair. Even if a better universe might yield a whole collection of Scheib’s writing, this is a very welcome gesture.

I should add that there are many other excellent reasons for owning this box set, and that Scheib’s essay covers most of them. Here’s one hefty sample of her prose at its most Farberesque, describing The Hitch-Hiker:

The striking compositions (two blanketed figures like shrouded corpses separated by a narrow stream from a gun-cradling madman whose eye cannot close even in sleep), the on-pulse kinetic editing as heightened-consciousness flow (the alternation of dramatically linear action sequences and frozen, impossible nervous waiting-time), the spatial integrity of a determined and determining terrain (the pitiless topography of rock-bound, horizonless Mexico over which hovers an ever-present death), the gritty but never “degrading” physicality of undécorized, unsymbolic milieus (a haphazard, surprisingly well-stocked Mexican grocery store, a dusty little filling station), and the full utilization of contrasts between day and night, inside and outside (the constantly revitalized and restructured tension between the three men in their fixed car positions and even more fearful range of possibilities outside the car, the stillness and pregnancy of the night and the terrible clarity of the day)—these are elements very hard at work in all of Lupino’s films, and very much responsible for the mysterious “feelings” critics are willing to ascribe to her films while denying to her the credit of creating them. But here, in the familiar framework of a suspense actioner, these elements magically regain their “legitimate” functionality.

I doubt Farber ever published a sentence quite as long as the first one quoted here, but then again he also never wrote about Lupino as a director, even when he was offering a sidelong slam of The Hitch-Hiker as “meatball melodrama” that was only a fraction as polemical as Scheib, who puts all her observations to useful work. This prose has legitimate functionality, with plenty of magic and without any scare quotes.

***

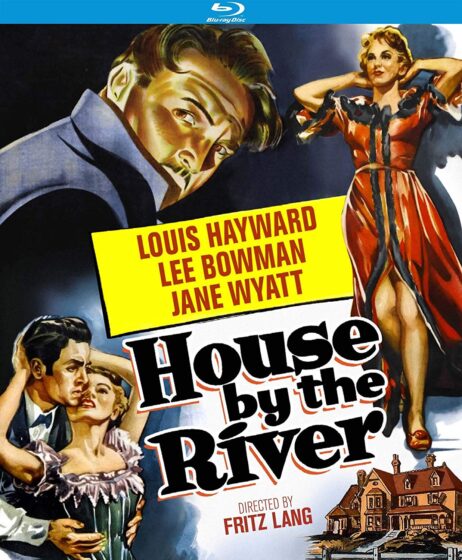

How many truly polemical audio commentaries do we have? Not too many, I would wager, and surely one of the liveliest is the one Melbourne critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas gives to Fritz Lang’s period noir House by the River (1950) on a lovely Kino Lorber Blu-ray. Taking vigorous exception to various male critics’ description of the central murder of a maid by a novelist (Louis Hayward) as the consequence of an attempted “seduction,” she properly defines it as an outright sexual assault, fittingly cross-referencing her objections with Harvey Weinstein’s tortured semantics. (On the same release, the late, great Pierre Rissient, interviewed by Todd McCarthy and filmed by Gary Graver, recounts how he gradually tracked down and released this neglected Republic Pictures gem.)

***

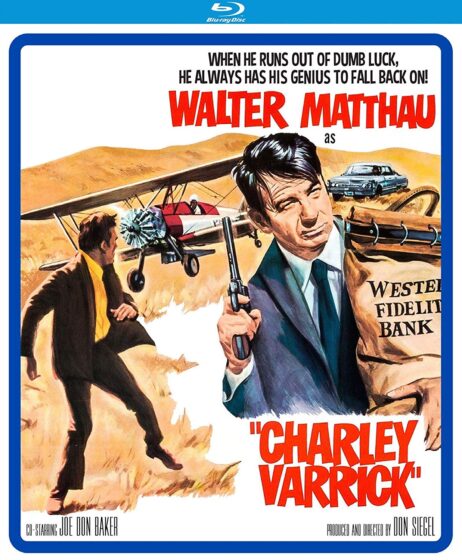

One should make a distinction between favourite films and memorable films, which aren’t necessarily the same. For me, a favourite film is one I can re-see countless times without becoming bored; conversely, if I remember a film too vividly, there’s usually less of a desire to re-see it, because I tend to prefer freshness to familiarity, even when it comes to films that I remember liking. The reason why I usually cite PlayTime (1967), Gertrud (1964), and Ordet (1955) as my three favourite films is that each time I re-see them is a different experience. To illustrate what I mean on a more mundane level, Charley Varrick (1973) is one of my favourite Don Siegel pictures because I tend to forget most of its details in between my separate viewings of it—and that includes forgetting what I find unpleasant and disagreeable in it (e.g., the sadism and brutality of the Joe Don Baker character, a sort of precursor to Javier Bardem in No Country for Old Men [2007], whose sanity is even scarier than the latter’s insanity). My latest excuse for re-seeing Varrick is a fine Blu-ray from Kino Lorber packed with extras, many of which justly extol Siegel’s gifts as a storyteller—which include a fine sense of what to exclude, as in the mainly wordless final sequence and the signature stoicism of Walter Matthau in the title role, both of which place an unusual amount of trust in the viewer to figure things out. This is tied to what makes Siegel’s best films both forgettable and rewatchable, and the tales of Isak Dinesen and the novels of Ross Macdonald similarly forgettable and re-readable: their fluidity. And fluids, of course, can evaporate.

***

Speaking of restored crime pictures, Flicker Alley and the Film Noir Foundation’s dual-format edition of Richard Fleischer’s Trapped, made for Eagle Lion in 1949, is such a class act in terms of its extras that it may seem churlish to question its being labelled as the “return of the lost noir classic.” It’s great for many reasons (spelled out in the extras) to see this film brought back from oblivion, but a classic it’s not. Starting off as a documentary about the US Treasury Department which quickly mutates into a thriller about counterfeiting, it winds up with a paranoid double- or triple-crossing plot in which all the characters are themselves counterfeits of one kind or another —an intriguing premise that lamentably goes nowhere, ultimately making me feel like a counterfeit viewer. Unlike Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin (1952), which has rigorous spatiotemporal concentration, loads of suspense, and strong, snappy characters, Trapped’s focus is so unsteady and so lacking in narrative momentum and characters that it virtually misplaces its central figure—an anti-hero played by Lloyd Bridges, who, unlike the psychopath Bridges played in Cy Endfield’s Try and Get Me! the following year, is arguably more of a type (although my editor, Andrew Tracy, maintains that his sheer viciousness makes him notable)—well before the end of the film, and has no one of much interest to replace him. (Rumour has it that this happened because Bridges became ill, and producer Bryan Foy simply ripped some pages out of the script in order to keep shooting.) Even so, I’m grateful for the extras, including Mark Fleischer’s stories about both his dad Richard and his granddad, the famous animator Max. It’s fascinating to discover that Richard originally wanted to be a psychiatrist, and to hear about his screenwriting partner Earl Fenton; it’s also sad to learn about the grim offscreen life of Trapped’s leading lady, Barbara Payton.

***

Dumbfoundedness and the mindless vicissitudes of fashion, continued: Leopoldo Torre Nilsson (1924-1978) is unquestionably a major figure in world cinema, a master of Gothic imagination and psychological horror, and probably the only Argentinian filmmaker widely known outside of his home country during the ’60s. Yet none of his 20-odd features is currently available in North America, and whenever I used to bring his name up with my Argentinian friends, it was as if a bad smell had suddenly entered the room. I don’t know whether the basis for this strange disaffection was political or aesthetic (maybe it was both), nor can I tell how much this may be tied to his alleged decline during the ’70s, but the fact that it still usually isn’t even considered a fit topic for discussion freaks me out, especially because I retain very warm memories of The House of the Angel (1957), The Kidnapper (1958), and Summer Skin (1961). I’ve seen some mediocre Torre Nilssons also—including, alas, Days of Hate (available on YouTube), his padded 1954 adaptation of Jorge Luis Borges’ “Emma Zunz” which was co-adapted (and subsequently disparaged) by Borges himself—but I continue to be on the prowl for others, which usually can be found these days only at out-of-the-way places on the internet.

At one such venue, I recently caught up with The Hand in the Trap (1961), which co-stars Francisco Rabal, won the FIPRESCI prize at Cannes the same year that Buñuel’s Viridiana won the Palme d’Or, and qualifies as the fourth worthy Torre Nilsson feature I’ve seen. (Like the other three, and unlike Days of Hate, it was co-scripted by his wife, Beatriz Guido.) It initially comes across as very Chabrolian before gravitating in the direction of Mexican Buñuel, even as the socioeconomic milieu also suggests Antonioni in his country-club phase. (Arguably the most apt adjective of all—possibly accounting for what attracts me and repels so many others—would be Faulknerian.) But in fact, Torre Nilsson is too good to be caught mimicking any of his peers, so it would be much more accurate to call this a quintessentially black and white Torre Nilssonian erotic/Gothic creepshow. Why oh why has the world forgotten what that means?

***

The Internet Movie Database has very strange notions of what “trivia” and “trivial” consist of. To illustrate this with examples from some recent digital releases, all of the following qualify, according to them, as “trivia”: Maborosi (on a Milestone DVD with a very detailed and informative audio commentary by Linda Ehrlich) is “Hirokazu Kore-eda’s directorial film debut”; Robert Aldrich “privately admitted that he wasn’t entirely satisfied with the way [Ulzana’s Raid, released on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray] turned out”; Room at the Top (another Kino Lorber Blu-ray) was “essentially the first British film to openly depict adultery and suggest that sex was an enjoyable act”; “much of the cinematography” and “some of the costumes and character make-up” of John Huston’s Moulin Rouge (released in a dual-format edition by the BFI) was “intended to resemble the poster art of Henri de Toulouse Lautrec”; Le petit soldat (a Criterion Blu-ray) was “completed in 1960,” was “Jean-Luc Godard’s second film after Breathless,” and was “shelved for three years by the French censors.” Not at all trivial, in contrast to the above, are the facts that Maborosi had an estimated worldwide box-office gross of $144,025, Ulzana’s Raid had an estimated budget of $1,200,000, Room at the Top had an estimated budget of £280,000, Moulin Rouge received PG certifications in Argentina, Australia, and Canada, and both the US and the cumulative worldwide box-office gross of Le petit soldat came to just $24,296—leading one to the unavoidable and untrivial conclusion that the film had paid admissions, and meagre ones at that, only in the US, and was shown free of charge everywhere else in the world. Thank you, IMDb, for digging up this extraordinary fact.

Jonathan Rosenbaum