Film/Art | Harun Farocki’s Inextinguishable Fire

Images of the World and the Inscription of War

By Andréa Picard

“The image always occurs on the border between two force fields; its purpose is to testify to a certain alterity, and although the core is always there, something is always missing. The image is always both more and less than itself.”—Serge Daney, Libération (reprinted in Devant la recrudescence des vols de sacs à main, cinéma, television, information)

“One of my strategies is to over-interpret or misinterpret a film. My hope is that something is being saved in such an exaggeration.”—Harun Farocki

“Harun Farocki’s film and video work is almost too interesting to be art.”—The New York Times

The memory is faint, slightly fuzzy, and distinctly beautiful, not unlike a blurred, black-and-white Gerhard Richter portrait. Seven years ago, I raced from Roissy Charles de Gaulle—post-trans-Atlantic red-eye, valises in tow—directly to the Le Reflet Medicis cinema in the Latin Quarter, just in time for the matinee screening of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s Class Relations (1984) which I had, until that point, never seen on the big screen. The film was being presented as part of a comprehensive Straub-Huillet retrospective organized by Philippe Lafosse, which was to consume much of my month-long winter vacation in Paris. Awkwardly dragging my luggage—imagine Gena Rowlands’ baggage in Love Streams (1984), minus the menagerie—I managed to squeeze into the cinema just as the lights began to dim. Packed beyond capacity, people, mostly young, spilled into the aisles, lounging on the red carpet as if to have their déjeuner sur l’herbe. Somehow, I found the last seat in the house, in the back row, and left my luggage scattered by the door, fully blocking the exit, correctly surmising that no one from this crowd was going to walk out before the end of the credits.

The French-subtitled print was gorgeous—Lubchantsky’s cinematography was on full display—yet I, despite my best and most discrete efforts, could not for the life of me stay awake, having been up for nearly 30 hours. I watched the film in a semi-conscious state, completely unable to follow the story (it’s Kafka, after all), and instead focused on images, sometimes with my eyes open and, at other times, closed, as I listened to the film in German, content to not understand the language, to be comfortably seated among l’Internationale Straubienne, to be in Paris where one can see a 35mm print of a Straub-Huillet film in the middle of a weekday afternoon. I’ve since seen the film again on DVD and was astounded by how little of the narrative stuck with me, but what did were two clusters of images in particular: the elevator shots (as an emblem of entrapment and capitalist class confinement or just my own claustrophobia?) and the scenes with Harun Farocki (a veritable yet nocturnal déjeuner sur l’herbe and him in a bathrobe), whose regal presence remained etched in my mind. Perfectly at ease within the Straubian mise en scène, chiselled, compellingly monumental, and with an air of insouciance, Farocki emanated what could only be described as star power. With handsome good looks and his striking physicality, Farocki transcended his character and both disrupted and enhanced the flow of the film, embodying a punctum-like presence, at odds with yet entirely fulfilling the film’s universe.

***

Farocki’s sudden and recent passing at age 70 has been especially tragic in light of his remarkable productivity of late. In the past several months alone, Farocki has had a major retrospective focus at FICUNAM in Mexico City, while his “direct cinema” documentary Sauerbruch Hutton Architects screened in competition at Cinéma du Réel, his machinima installation-films, Parallel I-IV, were presented at the Berlin Documentary Forum, among other places, and he worked on the script of Christian Petzold’s latest film, Phoenix, which is set to premiere at TIFF. And this is not to mention all of the individual exhibitions of his work that were already planned, including at Ryerson’s Image Centre, which will open Serious Games I-IV in late September. His current popularity can certainly be attributed to his prolific output and the contemporary resonance of his film and artwork—especially in the continued exploration of Vertov’s kino-eye and its inevitable development into Das Auge of war with its attendant mass-media-cum-machine imagery, including simulation games for pleasure, as much as for recovery from trauma—but also to the astonishing prescience of his older work, which not only created seminal blueprints for analyzing and especially decrypting images, but also ignited the contagion of archive fever that has consumed much of moving-image culture for the past two decades. Long considered “Benjaminian” in the author-as-producer sense—but also in beguiling ways, as The Arcades Project remains an interesting point of reference for some of Farocki’s work and research methodologies, and finds a fitting contemporary update in 2001’s The Creators of the Shopping Worlds—much recent writing on Farocki has turned to Aby Warburg and his Mnemosyne Atlas (which in great thanks to French thinkers like Georges Didi-Huberman, has enjoyed a major resurgence, especially in the art world).

It has perhaps too often been said that Farocki’s major contribution is (now was) his writing, he being “the best-known unknown filmmaker in Germany” to famously quote Thomas Elsaesser. His writing-thinking has been unquestionably important and influential: his conversational book on Godard co-authored with Kaja Silverman, Speaking About Godard, remains a landmark (and lively) text, as do many of his essays and articles from the German film magazine, Filmkritik (for which he was the managing editor from 1972 to 1984), and contributions to newer anthologies. Even his interviews are filled with enlightening theory, but in some ways more significant, they are brimming with a deep, unbridled cinephilia—one that revealed Farocki’s prominent iconological tendencies to be rooted not simply in the visual (the dry, the technical, and the spectacular in the true sense of the word), but in images from film history (thus, the seductive). Here, Serge Daney’s differentiation between the visual and the image is a crucial one, and Farocki’s great genius lay in his analysis of the two and, above all, in finding interest and great meaning by excavating from both. “I am a friend of the dictionary,” he proclaimed in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, and his use of a filmic thesaurus or encyclopedia—perhaps best exemplified in his 12-channel video installation Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (2006) (“A character only begins after they leave the factory,” he once said, intimating at the dehumanization of industrial labour in systems of mass production)—also included compilations of various kinds. These include instructional workshops and training exercises humorously deployed in How to Live in the German Federal Republic (1990) and surveillance footage in I Thought I was Seeing Convicts (2000), in addition to his thinking and speaking about Godard’s colossal Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998), and the lesser-known montage gem, La verifica incerta (1965) by Gianfranco Baruchello and Alberto Grifi, for which Farocki actively helped find a new audience.

In some ways, Farocki’s fascination with La verifica incerta holds the key to his oeuvre in toto. With over a hundred filmic works (some of which are cinema pieces re-worked into a variation adapted for the gallery, or vice-versa), Farocki had, for the most part, fulfilled his commitment not to produce images (though of course when he did, he did so wondrously, as can be seen in one of his late great films, 2009’s In Comparison) but to use and re-use them, to put them into a different context, thereby refuting the “naïveté of the single point-of-view.” Thus influenced by Straub’s Marxist social engagement, electrified by the ballsy antics of the nouvelle vague, which unleashed a sense of freedom for rereading, reinterpreting, and fictionalizing the archive of film history, and incorporating a Brechtian desire for a synthetical approach to the language of cinema (“in order for it to persist”), Farocki was in constant search for truth, an uncertain, unverifiable, even latent and mutable truth from images that were constructed as well as those that were “unintentional.” Drawn to the denial of meaning in surveillance footage and, increasingly, in graphic simulation, Farocki always brilliantly sutured these to a larger system of capitalist complicity and implicit forms of violence. With a marked focus on footage from social institutions—recorded in the workplace, the factory, the prison, the military arena, the shopping centre, the sports stadium—Farocki revealed a different sort of dictionary: one of symptoms, societal genre conventions as it were. In Deep Play (2007), for instance, Farocki proves just how mesmerizing and addictive football footage can be with replays that could theoretically continue ad infinitum despite the final score, not to mention the notorious Zidane head-butt, arguably a dramatic high point in football history—already mass-consumed, trafficked, and altered.

Farocki’s “ways of seeing” were less predicated upon signification and metaphor so much as upon re- and de-contexualization, and thus, destabilization and dislocation. His theory of “soft montage,” an associative form of editing that elicits the spectactor’s engagement, offered a discursive counterpart to what Daney identified as “montage obligatory” in his observations on “The War, The Gulf and the Small Screen” in which the French critic bemoans the lack of real images capturing the war, and, later on in the essay, as a marked pessimism takes over, the decline of cinema’s power as an art form. Farocki’s suspicion of the image could be better understood as a suspicion of the production and generation of images, one energetically matched by his curiosity for and the arguably obsessive research tendencies toward not only the images themselves, but also the ideology behind their sources. He once opined that cinema does not really have a field of its own, and therefore the search could be endless, reminiscent of Godard’s wordplay between le voir et le savoir.

“What we produce is the product of the workers, students, and engineers.” This salient decree from Farocki’s agit-prop manifesto The Inextinguishable Fire (1969), which traces the origins of the production of napalm used in the Vietnam War to the Dow Chemical plant, introduces a through line that would bind much of his film work over the next 40 some years. There will always be a “new product” that will elicit varying degrees of devastation, be it weapons of mass destruction or a new corporate culture or brand (A New Product, 2012; Sauerbruch Hutton Architects) that will dictate a sterile, totalitarian system. Even when austerity seemed to reign and the films adhered to a dry intellectualism, Farocki was prone to rebellious flashes, none more punk than as in The Inextinguishable Fire, when he promptly put out a cigarette butt on his arm, ingeniously bridging the gap between the unimaginable reality in Vietnam and the disarming presence in the cinema. “This small gesture,” he said, “responded to an iconoclastic intention directed against cinematographic apparatuses and in so doing confirmed, with a unedited image, the force and persuasion of the filmic image itself.” Donning a preppy suit and tie, with his hair parted to one side, the violence of the gesture seemed all the greater what with his schoolboy’s charm.

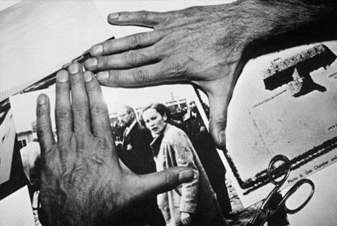

That hand (and yes, like in Bresson, the image of the hand dominates in much of Farocki’s work) is also seen framing photographs of the Holocaust in his masterpiece, Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989): a still image of a fetching woman, whose transfixing gaze finds that of the photographer, who, like the SS guards leading her toward her death, traps her movements. And more photographs, those which have, decades after the end of WWII, revealed the fatal “blind spot” of the evaluators whose review of aerial surveillance shots taken by an Allied aircraft failed to recognize that the photographs depicted the layout for the Auschwitz concentration camp. In Farocki’s hands (quite literally), this material is woven into a sharp, provocative, and multi-layered refutation of photographic reality, using many other tangents that build upon his argument in ways unconventional and intuitive, and employing a pseudo-Godardian double entendre with Aufklärung, the German word for both “enlightenment” and “aerial surveillance.” Cutting to the heart of media violence and the essence of an unspeakable evil and with searing humanism, Images of the World is one of the most influential, quoted, and urgent essay films, as relevant today as it was when Farocki made it.

Wresting images from one context in order to explore their hidden values (often lurking in the hors champs), and expanding his theories over multiple screens of late, Farocki has amassed an immense body of work—trenchant, incisive, radical, uncategorizable, and immeasurably influential. His generosity as a colleague, mentor, and collaborator can be felt in the calibre of his collaborations with Andrei Ujica, Matthias Rajmann, Christian Petzold, and his partner, Antje Ehmann, with his sense of humour and wonderment—his inextinguishable fire—never far from the work at hand. He will forever remain one of the most important artists of our time.

Andrea Picard