Papirosen (Gastón Solnicki, Argentina)

By Jay Kuehner

Genealogy is compelling as a means of accountability: ancestry as an historical index into the past that somehow illuminates the present. The desire for a legible personal history is always hopeful, taking memory as redemptive in its recovery of lost episodes, marginal lives, traumas and triumphs. And yet, for a film that is so clearly haunted by the past, and is shuffled with faded family albums and home movies, Papirosen is conspicuously absent of imagery related to its ostensible inception: Jews being erased from Poland during WWII, the point from which Argentine director Gastón Solnicki effectively traces his family history. In its eschewal of a redemptive narrative, and its elusion of an affirmative history, Papirosen mines the ambiguities of the director’s family in the present tense, tracing the legacy of history as it bears almost indiscernibly, yet irrevocably, upon quotidian family encounters. As an intimate portrait it less than flatteringly reveals a clan at wit’s end—not least from suffering Gastón’s omnipresent camera—while discreetly conjuring a half-century of displacement, disappearance, prosperity, and progeny.

It is this lack of determinism that paradoxically delivers Papirosen’s otherwise unemphatic line of inquiry a strange blow of pathos, akin to Polish writer Adam Zagajewski’s sentiment about watching Shoah (1985) in an American hotel room while a neighbouring party’s chorus of “Happy Birthday” drowns out the plight of Jews. Is the sense of helpless remove a cause for regret or relief? Solnicki takes his family as a delimiting factor, the view from which his decade-long, obsessively observational chronicle is circumscribed, and any claims of history are registered anecdotally rather than authoritatively. Even the question of father Victor’s veritable birth place and date—as if somehow confirming his identity as someone who was purely and historically contingent—becomes something of a plotline as he tries to secure an official passport.

If “removed” is the position which Gastón’s cumulative exposure is attempting to come to terms with, it is through the alternation of past and present, memorial and incidental, that he chips away at a forlorn essence of his family that even sorrow has obscured (in spite of enjoying class privilege, though money issues do surface). The film’s opening shots of two figures on a chairlift therefore become twofold: at once the director merely on winter holiday, gathering footage of his father and nephew Mateo, is gradually transformed into a symbolic image of two souls ascending in silence, scored to a voiceover of grandmother Pola recalling days spent hiding in cemeteries and scavenging for food in Grodno on the eve of war in 1939. That the two seemingly disparate threads become entwined is Papirosen’s quiet strategy, linked by the revelation of shared history and a formal design that uncovers heartbreak in unlikely quarters (Papirosen’s sound design, for one, sustains the tension of the chairlift’s creaking cable as a sonic motif of perpetual dread and possible release, subtly suggesting the cold rails on which human cargo was shipped out.)

“We arrived by boat to Argentina,” intones weary grandmother Pola (her low voice seems scarred by experience), while vintage images of the family cavorting in the capital city flicker before us, belying the story of survival that this arrival signifies. Cut to father Victor in the present, in tow to his daughter Yanina and his grandchildren while shopping somewhere in Florida, and an association of profound proportions has been established before the viewer has caught up on context, or even identified the family tree. From the Jewish ghettos of Poland to the arrival by boat on South American shores, from Auschwitz to a Jewish diner in South Florida, from the loss of entire families to the care of newborn children tucked away in strollers—Papirosen folds together four generations of history by fixing on unsuspecting points in a continuum. “We were at a dance when the war broke out,” says a friend of Victor’s over a meal at the diner in Miami Beach (Wolfie Cohen’s Rascal House, since closed), and the distinction becomes crucial as to what, exactly, is being remembered.

Papirosen trades in such contrasts, of a dance interrupted by war, of an unremarkable diner unsuspectingly occasioning memories of the Holocaust, of seemingly innocuous Yiddish songs that bring tears to the eyes of men. The titular song, about a boy orphaned in the war who must sell cigarettes to survive, is Victor’s weakness, a vulnerability that can’t escape Gastón’s search for meaning by way of his persistent camera (nor his wife’s insistence that he still needs a lot more psychotherapy). Perhaps the weight of this tune owes less to its sentimentality than its evolution, having originated as a rollicking dance that would become repurposed with lyrics befitting two World Wars.

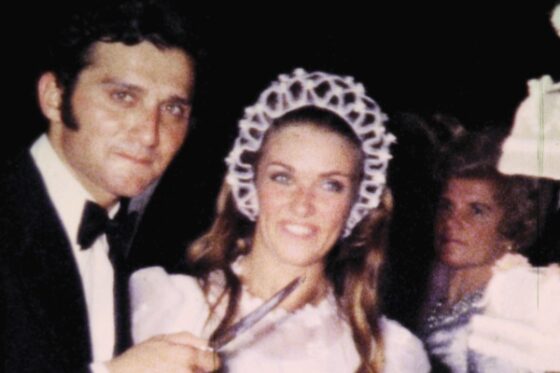

While Victor prevails as the film’s protagonist (and Pola its conscience), Gastón’s sister Yanina becomes something of a foil, as her imminent separation from her husband poses a threat to their children’s stability, clearly a concern to adoring grandfather Victor. The father/daughter conflict extends to such minutiae as the correct way to pack a suitcase, but there is an underlying sense that her career as a trader in rare dresses entails an unspoken compromise. Alternating scenes of Yanina then and now reveal her to have hardened with age, as Gastón’s gaze seems to extend retroactively into the past of faded footage in order to beseech her from the present moment. The effect is among the film’s more haunting features. (Middle brother Alan, by contrast, the sanest of them all, simply wants to distance himself from the entire family—with their consent, of course.)

Papirosen is less a memorial than an unsentimental, even ambivalent, elegy in-the-making, in which quiet devastation lurks in the details. Victor travels by train to the Czechoslovakia of his youth, where the buildings he looks for “no longer exist,” according to Pola. Instead of a grand historical confrontation with the past, Papirosen channels Victor’s impossible arc of a life into a simple visit to an antique shop in Prague, where he secures a little red wind-up toy car. Victor seems intent on recovering a youth that never really was. “Do you remember I used to play with these?” he implores Pola, while configuring his cast of vintage toy soldiers around a lone, seated Indian (who is Victor, in a symbolic sense, just as Robin Hood becomes his preferred fairy tale to read to Mateo). “I don’t remember what might have happened 60 years ago,” she rejoins, amnesia being both the source of survival and suffering among the Solnickis.

Papirosen transcends the home-movie genre by being ordinary; this is a look into the abyss that never strays from the surface of its chosen milieu. As such it’s a unique work of historiography, equivocally concerned with the wages of the past and the vicissitudes of the present; it drinks the black milk of daybreak while pausing, four generations hence, on young Mateo’s potential at tennis. From an opening shot of Victor shirtless, his stubbled head suggesting a Colonel Kurtz solitude, fils Gastón denudes père Victor both physically and emotionally, exposing his father as at once fragile and fearless. One definitive sequence consolidates the narrative undulation of levity and gravity, in which Victor occupies for the first time the bathroom in which his father Janek committed suicide (having “died of sadness”): framed in the mirror as split, as if inhabiting the memory, one hand on the door, moving both forward and backward, while a younger generation looks on with a diminished capacity for sympathy. Such is the case with lineage.

Gastón remains unseen, but is complicit in his absence. His visual chronicle becomes yet another means of family storytelling, a new kind of home movie that will also fade with time, to be looked upon by future Solnicki generations with nostalgia and, should Gastón’s legacy bear influence, with wistful circumspection. One can direct a film but not a family, a reality to which Papirosen inevitably succumbs; ultimately it is venerable Pola who calls “cut” once the memories prove too painful for the record. “Could we leave it for another day?” she begs Gastón, whispering until she can no longer speak. By then the camera has rolled long enough to remind us that, in the absence of any particular moral, there is still morality; that there are, to quote the director’s mother, “feelings that are universal.”

Jay Kuehner