Spotlight | Film Socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard, Switzerland/France)

By Andréa Picard

“The triumph of the demagogies is fleeting. Ruins are eternal.” —Charles Péguy

“The triumph of the demagogies is fleeting. Ruins are eternal.” —Charles Péguy

“What appears before us is an impossible story; we are confronting a sort of zero.”—Film Socialisme

“It takes strength and courage in order to think.”—Film Socialisme

LIBÉRER

FÉDÉRER

Those words, in big, blocky white letters, lingered with me three weeks after seeing Godard’s immensely anticipated Film Socialisme at its Un Certain Regard premiere on Monday, May 17, or, to admirers and dissenters alike, “journée Godard.” Indeed, Robin Söderling enacted this very pronouncement in the fourth round at Roland Garros, following the Swiss-French master’s prophetic words. Just one of the many instances where Godard’s latest (and perhaps final, though never say never) film essay has proven to be an oracular testament, all the more impressive considering its distended four-year gestation period. The arrival of Film Socialisme, it seems, could not have been more opportune or prescient. The downfall and subsequent humiliation of Greece (“HELL AS” and also, “hélas”); the corruption and financial meltdown on Wall Street, which continues to vibrate markets internationally (“Money was invented so that we don’t have to look each other in the eye”); the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico threatening a menagerie of animals (the gorgeously elegant, though slightly tattered llama, appropriately tethered to a gas pump at a Pop Art-inspired garage station owned by former Resisters both mirrored and contrasted with the oil-drenched pelicans featured on The New York Times homepage); anti-Arab sentiments launched in protest of Rachid Bouchareb’s Hors la loi met by the fascist bulk and swagger of the national guard; and most auspiciously, the pro-Palestine flotilla of activists raided and killed by Israeli soldiers parachuted from the sky all found resonance in Film Socialisme (in the latter two instances, the links came afterward when the film continued to sound out its densely layered and scopic messages). Add to this list the recent publication of the first-ever biography on JLG written and published in French, the 935-page tome by Antoine de Baecque, simply titled (or titled simply, and no less cheekily)

GOD

ARD

biographie

Or, “Godard biographie,” but if anyone has taught us something about the multivalent meaning of spacing, aphorisms, and wordplay, it is the book’s unwilling subject. And yet, following the initial screening of Film Socialisme, Godard was repeatedly referred to by the mainstream press as irrelevant, obsessive, bitter, solipsistic, out of touch with the world, relentlessly and tediously indecipherable; he was charged by The Telegraph with “blathering opacity,” and with having a message both contemptuous and empty. (Todd McCarthy’s distressingly moralistic Indiewire review surely remains the most repulsive.) Fancy that for a work that urgently, if experimentally, addresses contemporary global politics, rampant technological and aesthetic change, environmental and ecological catastrophe, cultural amnesia, and our culture of trash, vulgarity (Ryan Trecartin anyone?), consumption, and fractured communication, the inevitability of growing old, and the perpetually relevant theme of sport, with exalted mental athletics outweighing physical ones. Most misunderstood, perhaps, was the film’s virtuosic visual flair that harnesses the aesthetic charge of Godard’s arguments, and sees him exchanging resignation for inspiration (especially in children), and anger for moments of real tenderness. A male voice stands in for that of the director—“I don’t want to die before seeing Europe happy”—then later, a clip from Antonioni’s Lo sguardo di Michelangelo (2004). Naturally, the filmmaker’s reigning mischievousness and his demanding discourse remain amid this subtle fragility. Godard has long been fond of what Bachelard termed the implicit image, that which stems from the poetics of the imagination, and finds its perceptive place within a stream of thought and unconscious associations. Film Socialisme draws amply from Jean-Daniel Pollet’s 1963 collaboration with Volker Schlöndorff, Méditéranée, one of the most poetic of essay films, using text, image, and dissociative or hieroglyphic editing to convey a wistful, historical meditation in a land of myths. Editing images so that they emerge as the visual equivalent to his infamous aphorisms, Godard has increasingly become “interested not only in thought, but in the traces of thought.”

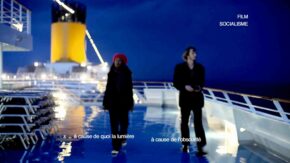

That Film Socialisme was much maligned by mainstream journalists is of no surprise given its free-form, fragmented narrative, and radically dissonant, but also polyphonic, soundtrack (funny, though, to recall Barthes’ semi-socialist maxim that we are all experts when it comes to sports and cinema). That Godard was accused of having nothing new to say (and worse, nothing to say, period) attests to the flagrant laziness and chauvinistic shirking of critics, whose derision undoubtedly grew from their inability to participate in the film’s socialist régime—a diet rich in contra/diction, dissonance, quotation, clips, crunching, crackling sound, varying visuals, poetry, aforementioned prophecy, idiosyncratic Markeresque history-making, and most pointedly, its own lingua franca. A polyglot concoction of mostly French, some Russian, and a smattering of German, Spanish, Italian, Hebrew, and Arabic, the film was shown subtitled in what Godard humourously offered up as “Navajo English” for its Cannes screenings, an already notorious sporadic wordplay of broken verse that lined the bottom of his 1.78 (16 x 9) HD frame, providing highlights or peculiarly poetic condensations of the dialogue and voiceover. As some of the sound is recorded quite crudely—with wind flapping against a cheap mic on a cheap camera—and prone to drop-outs and fading, the eccentric spacing creates not only a gap between words, but also, quite significantly for the viewer, a mental gap between sounds. For example, when the rhetorical phrase spoken in French in a female voice is “Because of what do we owe the light?” the response from a disembodied male voice is “Because of darkness,” while the haiku equivalent becomes the ironically obscure:

Light Obscurity

The image is that of the sea. Sometimes two and three words are joined together to form strange, playful, even silly portmanteaus. This added layer of text recalls the verse-like passages included in the booklets to the EMI soundtrack to the multi-lingual Histoire(s) du cinema (1989-98), not so much in its spacing but in the poetic distillation of the melancholic, monumental essay. (This hybrid translation cannot be used as a transcript for subtitles and instead functions as an aphoristic interpretation, adding an additional level of meaning to the already dense composition.) The script for Film Socialisme will be published in early July from P.O.L. but in French only, sans Navajo—his lingua franca, his Fibonacci (once called “Indian mathematics”). Godard clearly didn’t trust that Cannes would follow his presentation instructions (version originale seulement S.V.P.), having disobeyed him with Notre musique (2004), which he had explicitly requested be shown without subtitles. This time Godard took matters into his own hands, ensuring that the barbarians who crudely cut the queue to get into the Debussy just as quickly bulldozed their way out once they caught on to the dubious nature of the film’s English non-translation. There is an abundance to grasp in the film beyond its French text, but understanding the language assures a fuller experience of this complex, beautiful, and at times quite amusing work. The VOD version (which Godard has criticized, saying he would have preferred a well-thought out and executed distribution plan, such as parachuting teenagers into towns to conduct test screenings to see if a theatrical run would be possible and fruitful!) does not include the “Navajo English,” nor does the theatrical version that was released in France on May 19. Thus, Film Socialisme exists as two films quite distinct the one from the other, both fascinating, intricate, and nimble in their construction, and impossible to grasp in a single viewing, as is the case for so many of Godard’s films, regardless of how many languages one speaks.

“We can only compare the incomparable from the comparable.”—Film Socialisme

As did Notre musique and Godard’s (non)-exhibition at the Pompidou, Voyage(s) en utopie: À la recherche d’un théorème perdu. JLG 1945-2005, Film Socialisme employs a triptych structure (of parts of unequal length) that is markedly less Dantean than in the previous works. As de Baecque points out, Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville share a fascination for triptychs, for an organization of material that infers a past, present, and future, but also an image, another image and what lies in between, that which Godard calls the “true image.” His late period has repeatedly demonstrated an interest in a critical cinema, an art that interrogates itself by giving form to its history as much as providing a history to its art form, punctuated, of course, by the personal concerns of its maker—ones which presumably need no repeating here as they are resolutely, recognizably Godardian. Chris Marker also evidently comes to mind, but at Cannes it was Oliveira, whose sublime The Strange Case of Angelica echoed most profoundly with Film Socialisme. Sharing their theme of the transition into the digital age (an analogue camera here, a typewriter there) with its attendant philosophical implications, threatened histories, and ancient traditions (not to mention the ecological implications of these and the philosophical implications of ecological change that Godard has raised in recent interviews), and a surprising, almost jubilatory use of experimental cinematic techniques (Oliveira’s rudimentary, Mélièsian use of CGI was one of the most enchanting displays of magic until Uncle Boonmee), Angelica and Film Socialisme’s tackling of new, hybrid forms put them at the forefront of those continuing to expand cinema’s vocabulary and its visual potential. Their lamentations for a time past are expressed through contemporary means, conscious of the moral implications of their choices, and revel in the newness of creation. Perhaps most important of all, they adhere to a complete and utter freedom of expression beholden to no one except themselves. Agamben’s notion of contemporaneity aside, Oliveira and Godard live for the cinema (with 180 years between them!) and every frame, every composition suggests as much. (While Oliveira experiments in medieval grisaille, Godard opts for a hot, Fauvist palette, first explored in the searing second half of Éloge de l’amour [2001], then in the blazing, Apollinaire-riffing “Hell” opener of Notre musique.)

The first section of Film Socialisme, or “movement” (as this film, also, is about notre musique, our harmonies and disharmonies), takes place on a cruise ship touring the Mediterranean; the second follows the French family Martin who run a garage and are hounded by a camera crew after one of its members announces a candidacy for the local elections; and the third is a coda collage which ranks as some of the most inspired passages in Godard’s late period, perhaps of his entire career. The image of two red-headed parrots introduce us to a Noah’s Ark crossing Godard’s mythic Mediterranean comprised of Africa (“Alger, la blanche”), Palestine, Odessa, Greece (Hellas), Egypt, Haifa, Napoli, and Barcelona, where tourists touch down at the foot of Western civilization. “Vive les vacances!” as Europe lays in decline, wearing bloody stains embodied by the AIDS epidemic in Africa and the occupied territories in Palestine. With footage shot by four cameramen (Godard, his producer Jean-Paul Battagia, frequent collaborator Fabrice Arragno, and his nephew Paul Grivas) in a sort of cinematic socialism, the first section is a patchwork of images from hi-gloss HD with bold blocks of colour to lo-grade surveillance footage, cell phone images and badly degraded video with psychedelic visual interference, all colour-enhanced and gorgeous in their own way. The glowing, pulsating threat of destruction is heightened through elliptical montage and by the meticulously multi-layered surround-soundtrack, which ensures challenging eye-ear coordination not dissimilar, in fact, to Michael Snow’s La région centrale (1971).

“Abandon ship, abandon ship” can faintly be heard from a voice offscreen referencing the apocalyptic finale of Oliveira’s A Talking Picture (2003), which similarly posits a pre-Babel sea crossing through the fading histories of the founding Western empires, and an inevitable calamitous end. Godard demonstrates a cruel edge to his cynicism in the way he shoots unsuspecting tourists, especially the retirees whom he chastises, not for growing old, but rather for retiring. But the tourists do not abandon ship; they are there to have a good time, travel and enjoy their retirement, consume, and photograph everything, above all themselves and the sea. As Godard also does. Screens are present everywhere, and so are references to the Crusades and the Exodus. Cameras and coins exchange hands, and hang from their necks and rest in the beautiful bosom of an adolescent girl. Goldberg. The mountain of Jewish gold that built the Mecca that is Hollywood. A lovely Russian spy rehearses historical trespasses and a former Nazi endorses the end of memory. French philosopher Alain Badiou delivers a speech on Husserl to a large, empty room filmed in a long shot emphasizing the space and weight of absence. Godard says an announcement was made over the loudspeaker inviting all passengers to attend and not a single soul showed up. Why would they, when their options include a buffet, a nightclub, a casino, a dip in the pool, an aerobics class, and contemplation of the vast, open, cerulean sea? Badiou expounds upon ancient geometry, from whence the film has come. A return to the origins and patterns of European Mediterranean antiquity invokes circularity and a cross-cultural, geographical expanse—likely based upon French historian Fernand Braudel, who has long been an influence on Godard and whose most famous work is his Mediterranean treatise—which transcends the sea. It is to the desert where one must travel to find images, like when the altar of God literally exists in a nightclub cum casino. Or when a camel carries a big television screen. QUO VADIS EUROPE on your floating Las Vegas?

“Money is a public good.” “Like water then?” “Exactly.”—Film Socialisme

Good/goods. Pilfering clips from Pollet, Rossellini, Eisenstein, Chaplin, Ford, Varda et al., Godard makes like his subjects and pathologically steals images from the world (and the inscription of war). Once a klepto, always a klepto, but not when one believes, however paradoxically, that artists have no rights, only obligations. While the patriarch of the Martin family wants to decamp for the Midi to escape their depressing life of paying bills, the socialist pull of communal property seems the ideal. “France would be better off if the verb ‘to have’ did not exist.” But he and his wife have no answers to give their children who demand an explanation of the virtues upon which their nation has been founded. Here Godard initially seems to identify with the dour, embattled father with do-good intentions, but it soon becomes clear that his alter ego is the blond-haired son decked out in the bright red CCCP shirt. His refreshing indignation, vitality, roaming hands—which copy Renoir paintings in order to resuscitate past landscapes—and his obsession with women’s asses seem to suggest the director’s return to youth. The boy is also the only one, other than Godard, to utter the film’s already famous final decree, “NO COMMENT.” While the camera crew pestering the family is a tired routine (though not as preposterous as Patti Smith ambling about the cruise ship as sole member of a non-Imperialist America), the notion of being besieged seems personal and suggestive, alas, of the desire for family comfort amid shared resistance. “The dream of the State is to be one. The dream of the individual is to be two.” If only we could learn to liberate and federate.

“We’ve entered into an era with the digital wherein, for different reasons, humanity will be confronted by problems which will not have the luxury of being expressed.”—Film Socialisme

Godard: “At the end of his life Chardin would say: painting is an island that I approach little by little; at the moment it appears quite hazy. As for me, I will always paint in my own way. Whether it be with a pencil camera or with three photos.” The final section of Film Socialisme soars with aleatory rhythms, reminding us through a rapid montage of images (of war, peace, and Varda’s trapeze artists) that the final stage of Godard’s art-making has not strayed far from his Dziga Vertov period in tenor, yet has significantly in its palette. Le vent d’est has come around again, like tragedy in Athens. Some of the victims have remained, while others have become aggressors, as in the picture of Israel that so preoccupies him and so disturbs his dissenters. As he becomes increasingly removed from society but with a sharpened gaze, Godard’s painting grows ever more pertinent, exquisite and moving, not unlike Cy Twombly’s, imbued as it is with the knowledge that with a touch of a button, history can be all but cleared. Not simply of just an image, or of a just image, but of all images.

Andrea Picard