Festivals | Rotterdam: M for Mellow

By Calum Marsh

Dissonance was in the air in the Rotterdam. There persists, of course, a contradiction at the heart of every international film festival: thousands are asked to converge together in a city so that they may spend their time alone in the dark, which is a bit like wasting a tropical vacation watching TV in your hotel. But over the years International Film Festival Rotterdam has, like the reconstructed port city in which it is set, cultivated several contradictions of its own. The most flagrant is curatorial: there are too many films yet not enough worth watching. During the festival you could hardly wade into a postprandial conversation without drowning in such complaints. A cursory glance at the daily schedule, with its hundred-plus colour-coded obscurities scattered across the page, is enough to send even weathered veterans fleeing from the Pathé. No critic could hope to navigate this mess gracefully. Pedigree was rarely helpful. Hype, which governs more populist festivals, was absent. You tended to hear more warnings than recommendations. Faced with this glut, what should anyone bother to see?

This isn’t simply a matter of excess. This year nearly 400 shorts and features screened over IFFR’s ten days, but that’s hardly any less manageable for the average attendee than TIFF’s much bragged-about 288. The difference is that TIFF’s slate is comprehensible even at a glance: between its middlebrow world premieres, Oscar-courting prestige pictures, anticipated auteur efforts, early-year holdovers from Cannes, and reliable oddities from Wavelengths, TIFF makes it easy to know both what to see and, no less significantly, what to avoid. The IFFR program, by contrast, is considerably more opaque. Its extensive program has been divided into broad sections including Bright Future and Spectrum that, in their vagueness, prove woefully unhelpful. A festival that prides itself on fostering new talent, IFFR seems perversely drawn to the untalented, which is to say that its discoveries for the most part deserve to remain unheard-of. The program’s only known quantities, therefore, are relics from last year’s festival circuit, revivals and retrospectives, big-ticket American indies enjoying their Dutch premieres, a handful of titles faintly buzzed-about the week before in Park City. It should come as no surprise that many critics regard Rotterdam as an opportunity to play catch-up.

Here’s another contradiction: where most festivals orient themselves around a carefully assembled competition lineup, Rotterdam seems intent on making its once-respected Tiger Awards slate a veritable wasteland of amateur cinema. Every day, it seemed, I talked to another weary critic who had just endured one of these dismal efforts, until advance word had swept in on each with increasing animosity. I only saw one of the 15 nominees: Tatjana Bozic’s Happily Ever After, an insufferable bit of Dutch navel-gazing that handily proved the worst film I saw during the festival. That Rotterdam could earnestly position these films as the festival’s most high-profile program betrays the extent of the disconnect between their priorities and those of the international attendees: the Tiger Awards section provides a meagre attraction for critics, filmmakers, and industry professionals whose experience at other festivals the world over makes the bulk of the program redundant. As IFFR consistently loses major early-year European premieres to Berlin, the emphasis on the Tigers lineup suggests a canny shift away from premieres they couldn’t get to films they already have.

The “central theme” of this year’s festival, apparently, had to do with “The State of Europe,” and to judge from the calibre of European premieres on display the continent is in a dire state indeed. It’s an irony typical of the festival that its most compelling films, despite the thematic suggestion, hailed from Chile, Mexico, the US, and the Philippines—in other words everywhere but Europe, where the films tended instead toward the uninspired and overly familiar. The program bristled with banality: from Claire Simon’s Gare du Nord, which was like a Hollywood remake of Museum Hours (replete with chance encounters, a romantic subplot, and even a ghost), to the Larrieux brothers’ Love Is the Perfect Crime, which was so light and airy it seemed as if it might disappear altogether: the EU provided little to write home about. A colleague reflected one evening that many of the European films on offer seemed ineffectual in a way that suggested political fatigue; perhaps the economic crisis had exhausted young filmmakers, rendering all but the EU’s most volatile states (Greece and Spain in particular) incapable of radical thought or action. In any case, my attention gravitated elsewhere.

First, to Chile, from which Alejandro Fernandez Almendras emerged with his third and best feature to date, To Kill a Man, which three days into the festival was awarded the Grand Jury prize for World Cinema at Sundance. To Kill a Man poses a simple question: What does it take to murder someone? The answer proves no less straightforward: It takes a lot. Almendras understands that the act of murder doesn’t need to be embellished unnecessarily: the drama inherent in taking a life only gains in effect when the action is played straight. Here the murderer is Jorge (Daniel Candida, excellent), a milquetoast family man accosted by a gang of local hooligans. The gang’s leader, Kalule (Daniel Antivilo), gradually bullies his way into the role of the victim. The film’s title, of course, renders the act to come inevitable. As a result we are attuned to the details: the exasperation of living in fear, the uselessness of the police in protecting people, and, finally, the complications involved in disposing of a body. As you might expect, Almendras is interested in the moral weight of murder and the toll it takes on Jorge, whose guilt soon encroaches on his life. But the film also hones in on the act itself. Almendras wants to show us that it’s not only hard to deal with murder, but to actually do it, too. To Kill a Man is an intensely physical film. Almendras doesn’t let you off easy: he makes you feel the act.

The North Americans, meanwhile, yielded an appealing languor. Fernando Eimbcke, the Mexican filmmaker responsible for Duck Season (2004) and Lake Tahoe (2008), found much acclaim at TIFF and NYFF last year with his latest feature, Club Sandwich, which arrived in the middle of Rotterdam like a much-needed afternoon nap. Bone-dry and understated almost to the point of self-parody, the film seems refreshing for precisely how little it aims to accomplish: rather than wallow in some sweeping reminiscence of youth, Eimbcke carves out only a sliver of the usual coming-of-age narrative and somehow makes it seem new. His material is wafer-thin: a young mother and her teenaged son are enjoying a poolside vacation at a discount resort when a pretty girl makes waves with a show of budding lust. The kids are eager to put their newly pubescent bodies to work; the mother gets jealous; the drama you’d expect ensues. What’s surprising is how vividly Eimbcke captures the details: every gesture of affection (and protection) feels exactly right. The film plays out delicately and it doesn’t strike a false note.

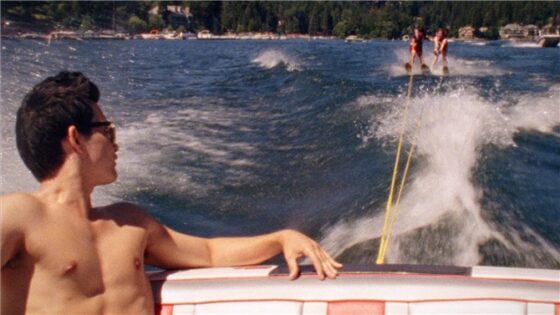

One last contradiction: most festivals overwhelm by design, and yet Rotterdam, despite its indiscriminate sweep, remains a surprisingly casual experience. Call it a kind of Dutch insouciance. Everything, in other words, seems “mellow”—the presiding sentiment of Lev Kalman and Whitney Horn’s L for Leisure, perhaps the festival’s only genuinely pleasant surprise. An episodic period comedy set in the early ’90s and shot on 16mm, L for Leisure is the kind of American independent film you rarely see anymore: hand-crafted over four years, idiosyncratically stylized, and made totally out of step with current trends, it has more in common with Gen X indies like Slacker (1991) and Metropolitan (1990) than with the exponents of mumblecore. Its ironic group portraits of graduate students drinking and lounging around seem at least loosely indebted to Whit Stillman and Hong Sangsoo, but the approach to comedy is harder to place; it somehow feels both understated and over-the-top at the same time. (Sample exchange: “I’m feeling really mellow.” “Oh you are? Here, have a drink of my Snapple.”) This rhythm—this mellowness—proves peculiarly seductive. And deeply funny: Kalman and Horn have a knack for finding humour even in their pauses; I often laughed as hard between punch lines as with them. Watching felt like being stoned—suddenly everything seemed funny. There’s something vaguely ridiculous about travelling halfway across the world to a festival whose best world premiere is American. But maybe that’s just part of the dissonance.

Calum Marsh