Cannes 2013 | Genocide Party Day: Death March, The Missing Picture, The Last of the Unjust

By Christoph Huber

Daily reporters at film festivals dread few demands from otherwise uninterested editors as much as “the festival’s overarching theme”: along with weather reports, these requests crop up with dispiriting regularity. As if a limited selection of movies (circumscribed by all kinds of necessities and strategic manoeuvers, at times more than artistic merit, it seems) arrive in a parcel with a neatly tied ribbon announcing “economic crisis,” “family histories,” or “female empowerment,” etc., emblematic of mainstream culture preferring the hierarchies of marketing guidelines to walking down the thorny path of submitting to an artwork’s own, possibly intractable, logic. Also, not any theme will do. Ironically, given the eventual Palme d’Or, for a while this year’s Cannes shaped up as the “penis festival,” but for some reason this was absent from the press coverage. On the other hand, of course some selected films are bound to be connected by various factors, and usually programmers go out of their way to stress obvious thematic resonances. Thus, one of this Cannes’ better stretches happened on Sunday, May 19, 2013, known in critics’ shorthand as “Genocide Party Day.”

A Holocaust reference greeted Quinzaine excursionists in the morning (in Serge Bozon’s Tip Top, a sympathetic experiment, but only successful in spots), before Un Certain Regard’s afternoon delights consisted of a studio-bound meditation on the Bataan Death March by Filipino Adolfo Alix Jr., and the latest entry in Rithy Panh’s ongoing documentary exploration of the Khmer Rouge Death Machine. The day was capped by a full evening’s worth of entertainment Hors Compétition with nearly four hours of Claude Lanzmann’s last reworking of leftover materials from the rich archive accumulated for his groundbreaking epic Shoah (1985). If that sounds glib, it may be taken to reflect the weird Cannes experience, itself a kind of death march from one line to the next amidst market-driven and stargazing masses, furthered by a new, if inconsistent, no-water-bottles policy in the Palais des Festivals that fosters all kinds of dehydrated hallucinations, especially with little pause between the screenings, making for eight painful hours in a row in the legroom-challenged Salle Debussy. Meanwhile, even the weightiest subjects threaten to volatilize in the face of calculated “themes” and eagerly publicized hype: genocide—apparently no matter which type—today, epic lesbian sex tomorrow. It is worth noting that European commentators picked up on Lanzmann’s specious introduction to his film, recounting Lanzmann’s refusal of festival director Thierry Frémaux’s competition slot. Tellingly, the commentators’ consensus was that a film of such moral force and historical importance would have towered over the competing flyweights, their conclusion belying the filmmaker’s undoubtedly heartfelt assurance that his grateful kiss for Frémaux was not “un baiser de Judas.”

Caveats aside, this day of enforced seriousness provided enthralling surprises and meaningful connections, despite an underwhelming beginning. Death March, though trying to one-up Josef von Sternberg’s Anatahan (1953) in stylized, stage-bound abstraction (this time, not even the water is real!), seemed too self-conscious even as a stilted exercise in surreal nightmare monotony, from its black-and-white seriousness to the artificial sets and the deliberately drawn-out dialogue delivery. Even the final movement into actual nature feels less liberating than the final twist in a well-intended, but eventually airless concoction—even as its earlier, entirely unexpected, ridiculously bold intrusion of overdubbed farts were the only showstoppers to its mandated solemnity. But both Panh and Lanzmann startled with unexpected turns in what looked on paper like obvious continuations of their respective cinematic life-tasks of terror-regime examinations, branching out in stylistically unprecedented and illuminating ways.

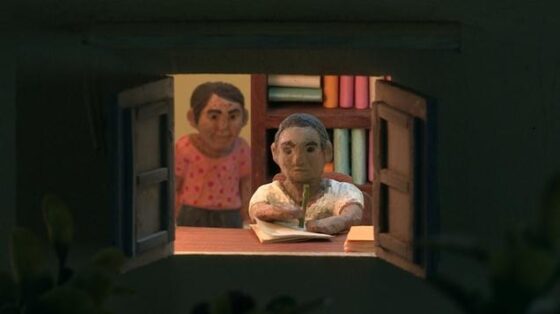

The eventual Un Certain Regard prizewinner, Panh’s The Missing Picture parts with the formal orthodoxy of his previous films on the subject like S-21: The Khmer Rouge Death Machine (2003) or Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell (2011), for the first time using both found footage (documentary and fictional propaganda films made by Pol Pot’s regime) and voiceover narration, based on the autobiographical parts of Panh’s book The Elimination (an English translation of which was published earlier this year). “If I close my eyes, still today, everything comes back to me. The dried-up rice fields. The road that runs through the village, not far from Battambang. Men dressed in black, outlined against the burning horizon. I’m 13 years old. I’m alone. If I keep my eyes shut, I see the path. I know where the mass grave is, behind Mong hospital; all I have to do is stretch out my hand, and the ditch will be in front of me. But I open my eyes in time. I won’t see that new morning or the freshly dug earth or the yellow cloth we wrapped the bodies in. I’ve seen enough faces. They’re rigid, grimacing. I’ve buried enough men with swollen bellies and open mouths. People say their souls will wander all over the earth,” reads one significant passage, pointing to Panh’s most flummoxing innovation. The (fascinating) found footage aside, he uses handmade clay puppets to illustrate and occasionally expand on the voiceover—the voice clearly not Panh’s, further complicating the issues of representation.

As the camera pans through these tableaux morts, the frozen puppet plays nevertheless exude a sense of archaic, almost childlike wonder, clashing with the terrible recollections on the soundtrack. There is a spiritual dimension to Panh’s strategy, in that he is looking for the soul of the dead: “What is the soul? Earth, wind, water, fire,” he said when explaining his decision for clay figurines to Cristina Nord in a recent interview, adding that “statuettes have a soul.” But as implied by the title The Missing Picture and discussed in the voiceover, there is also a haptic quality that governs Panh’s memories: he remembers not so much images as the touch (which also brings to mind the perpetrators re-enacting torture in S-21, resulting in unconscious, thus horrifyingly casual illustrations of body memory). Panh’s burnt clay theatre meshes perfectly with the justified pathos distinguishing the narration, while—intensified by complex negotiations with the historical film material—he proposes a miraculous method to represent the unrepresentable.

No less shocking, Lanzmann’s The Last of the Unjust breaks with the rigorous approach its director previously employed to find a just way to talk about the Nazis’ mass murder of the Jews with film, including hitherto strictly avoided photographs and material from the hateful propaganda film Theresienstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet (1944), also known as The Führer Gives a City to the Jews, which posits the Czech concentration camp Theresienstadt as benevolent “model ghetto.” Like previous annotations, Lanzmann’s new work—his biggest and longest since Shoah—adds a new perspective to his mammoth Holocaust investigation and does conjure a complex portrayal of Viennese Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein and his controversial role as last (and only surviving) “Elder of the Jews” in Theresienstadt, using a 1975 interview with a spellbinding Murmelstein, testifying to the man’s remarkable memory, intelligence, wit, and education. (The film’s title stems from his self-description; in another remarkable instance Murmelstein describes himself as a “calculating realist…a Sancho Panza in a crazy world of Don Quixotes.”) The counterpoint comes in Lanzmann’s usual contemporary landscape shots of the sites of atrocities and memories, many times traversed by the director himself reading excerpts from Murmelstein’s 1961 book Terezin, il ghetto modello di Eichmann, which recounts his history in an entirely different tone.

As the film progresses, it becomes clear that The Last of the Unjust is also a self-portrait of Lanzmann, now 87, befitting a veteran trend otherwise represented by a couple of Quinzaine elders—85-year-old Marcel Ophüls’ amusing, though hardly amazing anecdote anthology Ain’t Misbehavin’ (Un voyageur) and The Dance of Reality, a baroque and dazzling comeback for Alejandro Jodorowsky, now 84. During the final passages, Lanzmann’s presence as interviewer becomes more prominent: at 52, he gives a dashing impression, with playboy-like sunshades and leather jacket, smoking, his laid-back demeanour punctuated by visible amusement. When they walk off gracefully, it’s a reminder that Lanzmann is looking back at a time when he was recording and bearing witness for the people who had endured the Holocaust, when their memory was alive. Now they’re gone, and he remains, the film’s title suggesting that he has become The Last of the Unjust. But as Panh, a director clearly influenced by Lanzmann, has successfully demonstrated, the excavation of history continues.

Christoph Huber