The Decade in Review | Quintín

Hong Sang-soo’s most recent film, Like You Know It All (2009), begins with a filmmaker arriving at a film festival in Korea, where he’s supposed to serve on the jury. Hong’s basic plots are usually triggered by his memories, and so some people call him a Proustian director, while others prefer Rohmerian, due to his portrayal of talkative relationships between unmarried people. And because he’s so Proustian and Rohmerian, people say he’s a French director, but I’ve never met anyone who’s struck me as so Korean (although I always think Koreans are always tremendously Korean, while Canadians aren’t all that Canadian).

At the beginning of the last decade I arrived in Pusan to serve on the film festival’s jury. Hong Sang-soo was also there. What I didn’t know is that I was entering a Hong Sang-soo movie. We smoked, ate fish, and drank soju like in his movies and, in the end, gave an award to Jealousy Is My Middle Name (2002), a film made by Park Chan-ok, a female former student and assistant of Hong’s; the film’s most unlikeable character is closely based on him. At the time, I didn’t know that, but two years later I did and, again in Pusan, while drinking in a restaurant and playing rock-paper-scissors with Hong and some of his friends, I asked about Park Chan-ok. Hong exploded in anger. “She should be more daring and have a life!” he yelled. I replied (everybody was a little drunk, I confess), “But she was daring enough to make a film about you!” Hong’s friends died laughing.

I’ve never had a serious conversation with the man since. Now that ten years have passed, and I am almost completely out of the film-festival circuit, those Pusan memories strike me as a remarkable experience. In the new century, South Korean cinema emerged onto the international stage, and Hong was one of the names that proved that the phenomenon was greater than a few films’ massive domestic box-office success. Somehow in the margins of the Korean wave exists this absolutely unique filmmaker whose films and daily life are so hard to separate. “I make films about myself, because that is the only subject I know about,” says director Kim in Like You Know It All. “I don’t make films that look pretty.” But Hong is not in the business of documentaries, not even in the twilight zone where it overlaps with fiction. Even if his films are absolutely accurate about social and psychological issues, and no one has portrayed modern South Korea and its contradictions in such a realistic way, the true source beyond them is more than personal experience—a sort of mathematical imagination, constructing plots based on the idea of the double, the ghost, the other side.

Hong is the king of number two: two men for a women (Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), two women for a man (Woman on the Beach, 2006), two chapters in a male-female relation (Turning Gate, 2002), two films in one (Tale of Cinema, 2005), two filmmakers (Like You Know It All), two countries (Night and Day, 2008), two everything. In his films, almost every character, location, plot twist, and love affair have an alternative. Being true, being honest—as I recall hearing Hong’s angry speeches about cinema—is the only thing that matters to him, but at the same time, the truth is never there: it’s a phantom. The secret of his filmmaking is staying true to the false: that’s why his characters chase truth like a mirage that’s always changing place and shape. That formal device is what makes his films so similar, yet so fresh and so free. Hong’s tales of male hysteria and female madness—those sad-funny stories where everybody cheats on themselves—is an organic labyrinth where all paths cross and destiny can go all ways at each crossroads, though the same sense of loss and frustration lies at the end of every path. And there’s no way out of this nightmare because the world is not a Platonic Avatar but a Hong Sang-soo film.

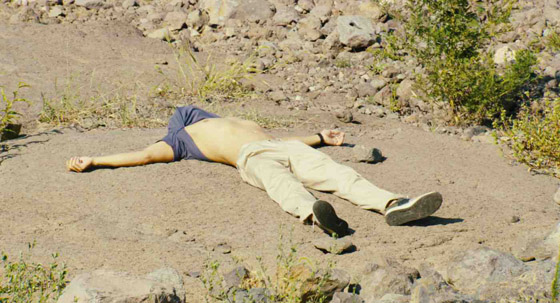

Quintín is a former critic and festival director, now based in a more or less Hong-style beach resort in Argentina.

Quintin