Together We’re Willing to Take Any Risk: The Films of Han Ok-hee and Kaidu Club

By Jesse Cumming

“There are two prejudices in pre-existing cinema: filmmaking is a male job and the movie should be fun. We, as outsiders, will break these biases.” —Han Ok-hee, 1974

In 1974, a group of students from the prestigious Ewha Womans University in Seoul formed South Korea’s first feminist film collective, Kaidu Club. Shepherded by the group’s de-facto president Han Ok-hee, the other members—who participated with varying degrees of involvement over the Club’s five years of existence—also included the painter Kim Jeom-seon, as well as academics and artists Lee Jeong-hee, Han Soon-ae, Jeong Myo-sook, and Wang Gyu-won. As the “Club” designation might suggest, the group was committed to both the promotion and production of experimental cinema, which was still in its domestic infancy. Both elements informed the Club’s official debut in July 1974, when they organized the country’s first experimental film festival on the roof of Seoul’s Shinsegae department store and presented their own works alongside films by peers Kim Jum-sun, Yi Jeong-hee, and the American Ed Emshwiller. A similar model was replicated, with even more emphasis on the Club’s own productions, in the 1975 and 1977 iterations of this short-lived but important event.

Kaidu Club was one of several collectively minded constellations of artists and filmmakers that populated South Korea’s cultural landscape in the late ’60s and early ’70s, including visual-art collectives like The A.G. (or Avant-garde) Group, the Shin Jun Group, and the Fourth Group. (The latter included Kim Ku-lim, who directed The Meaning of 1/24 Second, the 1969 short often considered South Korea’s first experimental film.) More dedicated film collectives included the early trendsetters Cine-Poem and Kaidu Club affiliates Moving Image Research Group, who presented early projects by Han in 1973, the year before the official formation of Kaidu Club and the experimental film festival.

The somewhat nebulous and interdisciplinary nature of Kaidu Club—which at various points also went by the name Kaidu Experimental Film Research Society, to designate their more academically oriented projects—is reflected in its cinematic output. While their filmography includes a number of collectively authored works, the majority of the Club’s projects were released under Han’s name, with other members contributing to the production on the periphery. Rope (1974) was one such film, signed by Han and presented at the 1974 festival. While a number of the group’s projects touch on themes of separation and isolation, Rope is one of Han’s most technically and formally contained pieces, constructed primarily out of single-frame animations of the eponymous object choreographed on top of a sheet in a studio. The manipulated rope—which can variously be read as a noose, an umbilical cord, or a film strip—is regularly accompanied by a collection of other squirming, shimmying objects (paddles, nets, pans, shoes, a soccer ball, an umbrella, a ladder, and more), as well as the body of the filmmaker and her impressionistic shadow. The film also incorporates fragments of documentary footage captured on the streets of Seoul, frequently sutured with playful associative montage, such as cutting from a net to fish in a market stall, or a close-up of the rope to a live snake. The film’s final moments are its most frenetic, with blurred, chaotic camera movements accented by splotches of blue paint floating on the surface of the black-and-white footage.

Kaidu Club emerged less than five years after Kim’s The Meaning of 1/24 Second, and it’s easy to see traces of the excitement and pointed experimentation of Kim’s dynamic film in Rope and a number of Han and Kaidu Club’s shorts—particularly its rapid-fire approach to assemblage and juxtaposition, an ambivalent relationship to the modernizing city of Seoul, and a decidedly DIY, freeform style that incorporates themes of industry, art, culture, politics, and commerce through an ambitious mix of documentary, animation, and flashes of a surrealist narrative.

While Han’s earliest films most often build upon the language of experimental film, the 1975 short 2minutes40seconds (which in fact runs a little over 10 minutes) more immediately embraces documentary. Across its runtime, the filmmaker(s) assemble an associative montage of moments that reflect contemporary life and culture in South Korea, with the still relatively fresh partitioning of the nation a central theme. As with Han’s other films, the editing is swift, and traditional elements—temples, prayer, art, woodworking, and more—are set against more banal, quotidian material of animals, sports, and children playing, as well as images of construction sites and other harbingers of modernity. There are flourishes of traditional avant-garde aesthetics throughout, such as near-abstract compositions of building materials and light on water, or technical plays with focus and shifting exposure rates. Wordless, the film is set to a booming score and occasionally heightened foley. One of the few motifs and repeated images is that of a barbed-wire fence, and each appearance appropriately serves to halt the film’s steady flow of images, if only for a moment. For a film that is positioned as a paean to citizens who dream of a united North and South Korea, the final result is appropriately cumulative, and the mosaic-like assemblage emerges as a rich time capsule greater than the sum of its individual parts.

Hole (1974) is one of Kaidu Club’s most enduring works, and proof of their multifaceted approach to filmmaking. The group’s interdisciplinary arts background is evidenced in the opening moments, which offer details of abstract paintings before shifting to a loose narrative about a young man who escapes from a prison cell into the metropolis before ultimately deciding to return. In lieu of dialogue or voiceover, the sound design is a mix of electronic compositions, surf rock, psychedelic funk, heavy breathing, and other audio effects. Visually the film is equally dynamic, notably for the way it interpolates and reworks multiple eras of experimental-cinema style into something distinct and specific, variously incorporating ’60s and ’70s materialist manipulations and other technical plays with solarization alongside Dutch angles and mysterious glimpses of hands reaching out from and over walls, images that wouldn’t look out of place in Dimitri Kirsanoff’s Ménilmontant (1926) or a ’40s Hollywood psychodrama. While one suspects Han and the group may have had exposure to similarly maximalist experimental work by their Japanese contemporaries Terayama Shuji and Matsumoto Toshio, the film’s Western influence is cemented by the end card (“FIN”), a testament to the influence of foreign culture available from local screening venues at the time, the history of which has been explored by scholars Oh Junho, Park Nohchool, and others.

Less official than any of the organized collectives active at the time was the loose group of cinephiles and intellectuals who populated screenings hosted by key cultural institutions in Seoul that permitted vital and influential exposure to international art cinema, including the Goethe-Institut, the French Cultural Centre, and the United States Information Service. It’s here that any discussion of Kaidu Club, their activities, and their artwork serves to be further situated in the context of ’70s Korean film culture, which is frequently considered the “dark ages” in most studies of Korean cinema, situated between the golden age of the ’60s and the New Korean Cinema movement of the ’90s. The decade was profoundly marked by the cultural policies of dictator Park Chung-hee, who had been the nation’s president since 1961. With the 1973 solidification of Park’s powers through the Yu-shin Constitution, the nation’s censorship laws were rewritten and strengthened, leading to tighter restrictions on content and more rigorous vetting of both scripts and finished films. These measures also informed the era’s commercial exhibition standards, with limitations on foreign films as well as independent shorts, forcing the need for alternative screening venues like the aforementioned cultural centres, cafés, and more.

Whether or not its popularity can be attributed to the importance of the Goethe-Institut, different scholars also note the prevalence and importance of the 1962 Oberhausen Manifesto for several of the groups and artists active in the Seoul scene of the ’60s and ’70s. Penned and signed by a number of German filmmakers (among them Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz, and Haro Senft) as a rebuke of their national commercial cinema, the text has erroneously been cited as declaring “papa’s cinema is dead.” It’s notable that this misconception made its way to Korea, however, given the slogan’s affinity with the principles of Han and Kaidu Club, who positioned their work against the patriarchal mainstream cinema that dominated their country’s film culture. Such antagonism was also explicitly directed against “Chungmuro,” a domestic place-name shorthand for the commercial film industry (à la “Hollywood”).

In particular, 1974 proved to be a major year for Korean film history, one where we can identify divergent stylistic forms that would influence the rest of the decade as well as later national cinematic developments, particular in terms of the representation of women. On the one hand is the release of Lee Jang-ho’s Heavenly Homecoming to Stars, at that point the highest-grossing Korean film of all time. An important entry in the genre of “hostess films” that dominated the ’70s commercial industry—“hostess” being a general stand-in for “prostitute”—the films shared connections with the Western “fallen women” films of decades prior, their plots typically laden with sexual violence and tragic endings. Scholar Yu Sun-young’s research into cinema of the “dark ages” stunningly reveals that “hostess or sex workers accounted for 87.5% of all female characters in films produced from 1971 to 1979.” While the reputation of Lee’s film and certain other hostess films have shifted over time, with some critics lauding what they see as a particular class consciousness, the films, the industry that produced them, and the policies that permitted their dominance were all targets of Kaidu Club’s criticism.

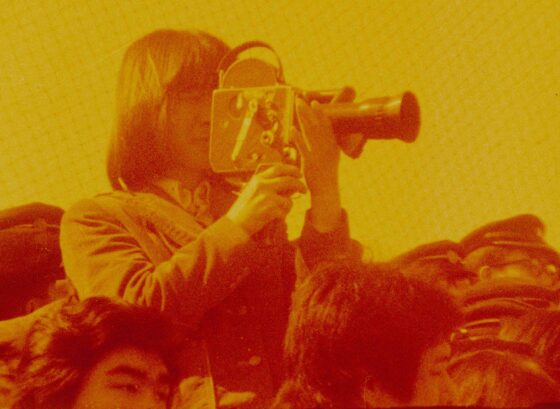

One of the later Han Ok-hee films produced during her association with Kaidu Club was Untitled 77-A (1977), a playful but loaded self-portrait of the artist as a stifled creative, and one of her few works to explicitly foreground a woman protagonist. The film opens with Han in a darkened studio, trimming 35mm film with scissors before splicing, assembling, and eventually projecting the fragments. Much of the projected film consists of yellow-tinted material, again presented as impressionistic collage. Like the earlier films, we see a mix of observational footage of pedestrians, artists, sports, and more, but here the footage also features Han and other filmmakers within the crowds, cameras raised to their eyes or, in one moment, laid on Han’s lap as she sits, slumped, in a city square.

Between these quick flashes, the film returns repeatedly to Han and her studio as she drapes reels of celluloid over her body and plays with her scissors, including snipping dramatically in front of a projector beam in a pseudo-expanded cinema performance. Eventually the film takes a turn for the macabre, as the scissors puncture a white wall and produce a mysterious stream-turned-splatter of fake blood. If the film displays the sense of darkness, frustration, and claustrophobia that also informs Hole and elements of 2mintutes40seconds, the final moments serve to rupture the atmosphere, as the darkened room is illuminated and Han is joined by a smiling collaborator to pronounce the film’s sole word (in English): “Cut!”

Although Kaidu Club splintered towards the end of the ’70s, its influence and importance are evident in the cinematic renaissance in the post-Park Chung-hee ’80s and ’90s, an era which not only saw the emergence of a new generation of feminist filmmakers, but also vital documentary practices. Likewise, the groundwork laid by the group’s early forays into exhibition appear as obvious precursors to the independent-minded Small Film Festival of the mid-’80s and the still-active EXiS Experimental Film and Video Festival. Han, for her part, temporarily relocated to Germany in the ’80s to undertake further graduate studies, but eventually returned to South Korea and to filmmaking. While never embracing the mainstream Chungmuro realm the group rallied against, her work in the ’80s and ’90s was more industrial and commercial, culminating in the 1993 IMAX film Running Korean, produced as a promotional film for the 1993 Taejon Expo.

Obviously far from the rough, bric-a-brac nature of Han’s earlier experiments, the film does evince certain shared qualities with films like 2minutes40seconds in its valorization of Korean arts and culture, here seen through footage of colourful musical performances as well as other craft work. (One shot even echoes the earlier film’s opening and closing, of a Buddhist monk ringing an enormous bell.) While the few hints of modernity and development seen in her earlier works are trepidatious and ambivalent, here Han utilizes montage to link traditional printing techniques to modern computer science and other technological developments in a style that is unsurprisingly proud; even the celebration of Korean art is updated, with textile and pottery work seen alongside a boyish Nam June Paik as he manipulates his mixed-media “TV Cello” sculpture. In the film’s penultimate shot, before a runner and a glowing sun, Han returns to a drumming ensemble, with the camera focused on a tricolour Taegeuk swirl on the drumskin’s centre, which adds yellow (symbolizing humanity) to the blue and red of the South Korean flag. The invocation of the design and its signification of balance seem fitting for an artist who has long championed collaborative work, and whose artistic output has served to locate and produce harmony out of seemingly disparate contrasts.

Special thanks to Kim Jiha for her assistance with this article.

Jesse Cumming