A Liar’s Autobiography: The Return of Alejandro Jodorowsky

By Quintín

More than 800,000 people follow Alejandro Jodorowsky on Twitter. Every day these lucky people get a couple of dozen pearls of wisdom (in Spanish) such as, “If you hate walls, you should learn to build doors,” or “The Visible longs for the Invisible, the Invisible longs for the Visible. You are also what you aren’t,” or even “Don’t clean your ass before shitting.” Born in northern Chile in 1929, Jodorowsky fled the country in 1954 to Paris where he became a French citizen, and also a writer, a psychoanalyst, a visual and mime artist, a guru, an actor, a magician, a Tarot expert, a comic-book writer…not to mention a charlatan. Jodorowsky is too much of everything.

And then, he is also a filmmaker. Jodorowsky gained his fame in the early ’70s with two surrealistic works, El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973). Shot in Mexico, those films dealt with gods, revolution, sex, violence, and other Big Issues. They made money in Europe and became cult movies, staples of the midnight-movie circuit during the era. But even people who watched them and liked them years ago are not quite sure whether they were really works of art, or just something daring, original, visually powerful and yet childish and pompous. That being my attitude, and not having heard about Jodorowsky in years—he’s not hiding or anything, it’s my fault—I suddenly learned that he has made a new feature, his first since The Rainbow Thief (1990), and also that there is a new documentary made about him, and that both were shown in the Director’s Fortnight in Cannes this year.

Jodorowsky’s Dune, directed by Frank Pavich, is a straightforward documentary consisting of interviews about the non-making of Jodorowsky’s biggest project, the filmic version of Frank Herbert’s then famous sci-fi saga (actually, he only adapted the first volume), which is maybe one of the most boring books in the history of literature. It indeed was a failure, but an honourable one: Jodorowsky managed to assemble a huge and detailed collection of storyboards with the help of French bande dessinée artist Moebius, brought Dan O’Bannon, Chris Foss and H.R. Giger on board, secured music by Pink Floyd and get commitments to act in the film from Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, and Mick Jagger, yet Jodorowsky and producer Michel Seydoux failed to finance the script in Hollywood.

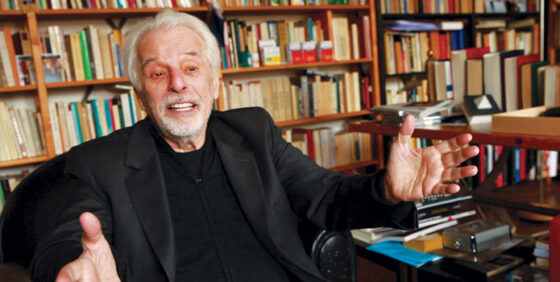

Jodorowsky appears throughout the documentary, speaking in Spanish and, for no apparent reason, in maybe the worst English uttered on screen since Tarzan. In spite of being in excess of 80 years old, Jodorowsky looks in great shape; he’s funny and histrionic. The guy takes great pleasure telling how he managed to seduce all those big names, and there are two moments that are particularly hilarious: when he reveals that he chose to make Dune without having read the book, solely because a friend told him it was great; and when he confesses how happy he was when David Lynch’s 1984 version of Dune turned out to be a massive flop. Of course, he is less convincing when he tries to persuade the camera that his Dune was the greatest thing on Earth, not an adaptation from Herbert but an autonomous piece about the coming of a Messiah, the rebirth of the Earth as living entity, and so forth. The presence in the documentary of Nicolas Winding Refn as a close friend and disciple doesn’t help very much, and reinforces the feeling that Jodorowsky is kind of a con man, that everything he says is informed by astuteness, opportunism, and self-promotion. Even so, he is not an unsympathetic character: his vitality and sense of humour are contagious. And in any case, his megalomania is absolutely harmless.

So after getting back in touch with the man through the documentary, I felt ready to watch the artist perform as a filmmaker (also as an actor, producer, writer and set designer) in The Dance of Reality (La danza de la realidad), shot in his native village Tocopilla in Chile and based on the eponymous book that makes up the first part of his autobiography, which he calls “imaginary but not fictitious.”

And then, to my surprise, I found that the film is great. And that Jodorowsky may be a false prophet, but he is a true filmmaker, one who explores the medium with absolute freedom and commitment. In The Dance of Reality, Jodorowsky plays himself as a ghost, while his son Brontis (who played a child in El Topo) plays his father Jaime. There are two stories in the movie, one about the coming-of-age of a child (based on Jodorowsky himself), the other about his crazy father, a Jewish communist who owns a lingerie shop and whose cruelty towards his son reflects the cruelty of society around him—a society characterized by misery, ignorance, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and violence under the military dictatorship of General Carlos Ibáñez. (Although it must be said that the chronology doesn’t exactly match up with the dates of Jodorowsky’s actual life.)

Each scene is a new discovery, a tour de force where something is invented and nothing is flat. Jodorowsky creates his own world with endless imagination: he comes up with crazy allegories, powerful parables, and a level of emotion, suffering, and joy very uncommon in contemporary cinema. Every detail is splendid, from the reconstruction of the village (where people are seen wearing masks and a dwarf advertises his wares in front of his shop) to the love stories of Jaime with the hunchback woman or the President’s horse. Jodorowsky’s taste for the theatrical and the extreme makes him close to Browning or Fellini, and maybe also to Syberberg, but his irony reminds me of Buñuel and even Ruiz, with whom he shares a vision of the sea and the experience of the Chilean provinces as a child. But I can’t remember a female character comparable to that of the mother, played by the extraordinary Pamela Flores, an enormous woman in every sense of the word, whose parts are entirely sung and whose naked body is just as much an anchor for the film as it is for her family.

Jodorowsky’s artistic output has to do with healing and with family, while his art and philosophy are based around the idea of the cure. His oeuvre tries to find out how to grow, how to live, how to love, how to educate oneself and others in order to close the wounds that birth and society leave in the soul. But this soul is in part a collective issue: parents are the children of their sons, and blood links make individuals part of other individuals. But also, they are thrown into history, thirsty for a relief that they can’t find in ideology or religion, wealth or power. Jodorowsky, the guru filmmaker, has an answer for that suffering, even as he himself experiences the core of universal pain through his father, whose soul is attached to the sources of violence, and whose need for love and redemption is so massive.

Brontis Jodorowsky plays both Jaime Jodorowsky as well as President Ibáñez, who is the object of his hate and whom he tries to assassinate; but both also bear a striking resemblance to the picture of Stalin that hangs on the wall in Jaime’s shop. The Dance of Reality works as an exorcism of an era where false and destructive dreams were also the hope for mankind, and when children were educated through abuse by their parents and by society. But Jodorowsky, one of these abused children, finally became as brave as young Alex is told to be in the film: he dares in his film to take on all of those issues, to speak freely about love and sex, fascism and communism and sorrow and pain and happiness, and to make his personal circus travel the world with brilliance. All he needs is some money, the money that he couldn’t raise for Dune. The Dance of Reality starts with Jodorowsky invoking the dance of money, and by the end of the film you can tell that his trick as a magician consists in making money dance for him, while pretending that he dances for the money. Even in that department, Jodorowsky is the biggest truth-teller among the liars.

Quintin