Super-Ornithologist: João Pedro Rodrigues’ Birdman

By Robert Koehler

It was a reminder of how much we desperately need stories and storytelling to make sense of the world when I saw one guy punch another guy in the face one evening on the UCLA campus in 1977. The guy getting punched had become all agitated arguing for his favourite book at the time—the fiction anthology Anti-Story—and claiming that we had all entered a new era where stories were dead. The punch to the face ended that discussion, but said something else: claiming that we’ve moved past stories is like claiming we’re past oxygen. Biologists know that we’re hard-wired for stories. Just as we visually perceive the world as we do because of the shape and position of our eyes, so we biologically require stories, and each is a result of evolution.

This as much as anything else can sum up one of the central ideas in João Pedro Rodrigues’ new film, The Ornithologist. Embedded in the film’s fascination with evolution is the essential nature of evolution itself, how it describes the nature of change and transformation. What begins as a science documentary becomes an adventure. What becomes an adventure transforms into a mystical fable. What becomes a mystical fable leads to a dark fairy tale partly in Latin, all of it is set in the far northeast corner of Portugal, a rugged and intimidating pocket of wild Europe marked by rivers and precipitous canyons. As much as João Pedro Rodrigues (with his creative and life partner João Rui Guerra da Mata) made the sense of place and time a central concern of his previous feature and even its title, The Last Time I Saw Macao (2012), it’s more extensive and ambitiously wrought this time.

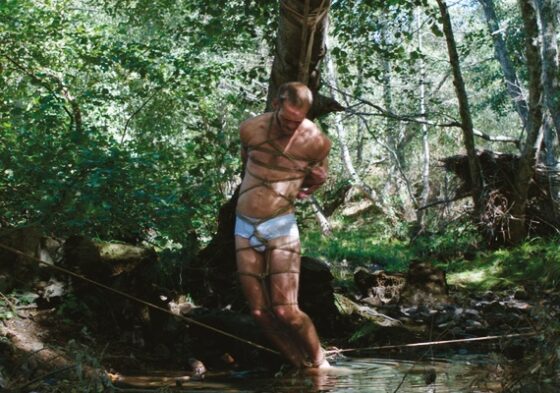

Rodrigues introduces an ornithologist (French actor Paul Hamy) exploring a river canyon area rich with avian wildlife on his trusty kayak, until, distracted, he’s washed into rapids and disaster. This leads to an absurd and nearly fatal encounter with a pair of insanely devout Chinese lesbian Christian pilgrims, having strayed far from the ancient Way of St. James, who toy with the notion of castration. This is only the opening salvo in an odd picaresque-yet-not-picaresque, a Western-yet-not-Western whose central premise is that things keep evolving, and you had better keep up. Shot in widescreen by Rui Poças, The Ornithologist is Rodrigues’ most thoroughly realized movie yet because he has the thematic and cinematic space to work out his ideas, and most importantly, he completely embraces the wonders and possibilities of storytelling, storytelling of the oldest kind, storytelling before plot points and third acts. Fernando, the scientist, is concerned with birds’ behaviour patterns and evolutionary development—evolution as it’s played out every day in front of our eyes, and in his case, in the view seen by his high-powered binoculars (a perfect stand-in for the movie camera). Fernando the observer becomes the observed, and the same evolutionary process that he measures takes over his entire existence, until he actually changes into the opposite of himself, or at least a very distant cousin—the beloved mystic St. Anthony of Lisbon. What the film and its constantly developing tale describe, by the story itself, is Darwin’s theory, not only of body but of mind. Somehow, only in the wilderness, where everyone from Jesus to Emerson made their greatest self-discoveries, are the real leaps of change possible.

Critical to Rodrigues’ sense of storytelling is his embrace of the Western and the adventure tale. “Anthony Mann and his Westerns were something I was thinking about a lot,” he says, and in the rocky canyons, precipices, and near-death experiences that Fernando experiences on his journey to become a new man—or “Super-Ornithologist,” as Rodrigues puts it—one finds the existential strangeness and transformations that set Mann’s great Westerns apart from everything else, including all other Westerns. Rodrigues’ way of cinema keeps us aware that we’re watching an adventure tale. At points, we’re immersed inside Fernando’s adventure and at other points we’re allowed to step outside of it and observe with our set of cinematic binoculars. And Rodrigues throws in a bonus play. He lets us see from below (Fernando’s view) and above (the birds, from eagles soaring overhead to a dove perched quietly in a tree), imagining the unimaginable: How do birds see us, anyhow? The Ornithologist imagines a possible answer.

Cinema Scope: What are the origins of The Ornithologist?

João Pedro Rodrigues: I wanted to be an ornithologist when I was a kid. That was the main desire behind making the film. It’s always been present in me. My parents were both physicists, so I was raised with a scientific and rational way of looking at the world. I feel things with a certain distance and coldness perhaps, and this comes from being a kid wandering in the countryside where my family had a home—we still have one there—and I wanted to make a scientific description of all the birds that were there in each season. I’ve had this scientific approach since an early age. Before studying cinema, I studied biology. Cinema interrupted this, and in a way I replaced this love of watching and observing birds in the wild and being alone, although I never felt alone because I felt surrounded by nature and living creatures. I was eight when my father gave me my first binoculars and field guide for identifying birds. As I was kind of a lonely kid, I started going to the cinema by myself when I was 15.

I’ve felt for some time this film just had to be made. I’m not very prolific. I never know which film will come next, and I honestly don’t know why this film had to come now. Perhaps it’s something connected with age. I wrote it in my mid-to-late 40s and I turned 50 this year. You think back to earlier parts of your life more often in your 40s and 50s than when you’re younger. So the film was a way for me to look back in time, not only to when I was a child, but to capture this spirit of adventure that I experienced. It also reminded me of the Westerns I would watch when I was young. My idea here was to make a Western.

Scope: With the recent economic crisis in Europe, that’s particularly been felt in Portugal, was this a struggle to get made?

Rodrigues: Yes, for sure. Our first draft was written in 2011, while we were working on the Macao film. When we applied for funding in Portugal, The Ornithologist was in the last group of grants given before the “zero year” when there were no grants for Portuguese cinema. We also had to apply for money in France, and that took a long time, and re-applying for more grants in Portugal also took a while. So I didn’t work on the script for a couple of years. In retrospect, it was fortunate that I had to wait before the money was “liberated” in grants that finally did come. I started reworking it and researching St. Anthony. As I don’t have a religious background, I didn’t know much about him. He’s a mythical figure who’s very important in Portuguese culture. I found out that he’s the most popular saint in the world, not only in Portugal. He’s even more popular than St. Francis. Meanwhile, I made a short, Morning of St Anthony’s Day (2012), the zombie film. It was my first approach to this St. Anthony theme, but in a more deviant way. The short looked at a post-apocalyptic celebration of St. Anthony, while The Ornithologist looks at St. Anthony more directly.

Then there was the next challenge of filming. The film changed a lot after I found the locations in northwest Portugal. It’s the wildest part of the country, along the Minho River that borders Portugal and Spain. In many of the scenes set by the river, one side of the shore is in Portugal and the other side is in Spain. In some places, you need proper permits to enter since many of the animal species are endangered. We filmed in a nature sanctuary, and the only other humans you might see are park rangers and ornithologists regularly tracking the birds to check on their conditions. I had this feeling of being in a place where few people had been, and even fewer had filmed. It already contained a mystery that I wanted to capture. It’s very rough and physical, and the landscapes are monumental. I wanted to shoot the actors—especially Paul Hamy—as if they had the same importance as nature. That’s why the film starts with birds, and then cuts back to him, and back to the birds—both have the same level of importance. I felt that the film could as easily have gone in the direction of the birds as the people.

We had a very precise and long location-scouting process. I wanted to shoot as much as possible in the wilderness. We put the camera in places where people hadn’t been for maybe decades or more. And where there had never been any cameras. My scout went on small roads and little trails and took photos, and I chose from these photos, went back with him to these spots, and then eliminated more and more places, until I finally decided on locations that were more dramatically interesting, and also that were accessible for the crew. We had a tiny crew, but it was still enough people that I had to consider if we would be physically able to get to these wilderness spots. Most access was by way of four-wheel drive and off-road vehicles. There was a spirit of adventure in the whole process. Our car broke down at one point in the scouting, and it felt kind of dangerous. I felt like when von Stroheim went to Death Valley to shoot Greed (1924), the sense that nature is stronger than you think it is. As the film is about how you look at nature and how nature looks back at you, I felt that nature was showing me hidden secrets and places that no one else had seen before.

Scope: There’s a huge idea that the film throws at the viewer, tied up with cinema’s difficult relationship with science and the irrational: the notion that we have a scientist character who encounters crazy mystics, but by the end is taken over by a kind of Catholic mysticism. Perhaps science is defeated by the mystical, or do the two merge? Are we watching an adventure story that takes us from science into the irrational or something else? Are we looking at a variation of the theme Kubrick was exploring in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where we start with one paradigm and end in another?

Rodrigues: Well, let me think about that. I’m a very rational person who’s not religious at all. But I’m very attracted to the idea of how religion is told. What made religion interesting for me was art. I learned about the stories of Christ and the saints through paintings, which is natural when you consider that the story of Western painting begins almost purely with depictions of religious stories and characters. When I finished high school, my father asked me where I wanted to travel, and I chose Venice. I spent two weeks in Venice doing nothing but looking at the paintings there, alone. I was 17. I saw the Tintorettos, Titians, Raphaels, Bellinis, all the works in the places where they were intended to be, which is amazing in itself. I learned a lot about the Biblical stories through looking at the work, and it touched me how the painters chose these iconic moments in the saints’ and characters’ lives to depict. And they show the saints before they were saints, when they were just human beings. And often these depictions are erotic and sexual. I found this all to be fascinating, and it really opened my eyes. This mix of the sacred and profane, which in the cinema we have from Buñuel to Pasolini, is so constantly present in these paintings. I’m hardly the first to point that out.

Scope: You use the images of San Sebastian, these vaginal-shaped wounds.

Rodrigues: They are eroticized images, and as such, they become desirable. The saints were the first superheroes. I like to think of the film as not just about St. Anthony. It’s about St. Ornithologist. The life of St. Anthony tends to be full of mythology, and it’s impossible to know how much in the life story is actually true. So I was already playing with myth and with fiction. João Rui and I took events from his life as a man—he was quickly canonized some years after he died in the 13th century—and reset them in the present. It’s a period, time-travelling film.

Scope: It also goes back into different past periods and at the same time is in the present.

Rodrigues: The warrior women on horseback speak Latin but are also wearing contemporary trousers and footwear.

Scope: You have a story that’s clearly in the present, but then as it moves along, the time shifts to a mythological past. But even with that past, it seems to change and never remains stable. It’s in a Biblical past, and a pre-Biblical past.

Rodrigues: Yes, and on another level, the film is always set in a place that has never changed since ancient times, in a natural world that hasn’t changed very much at all. Those rocks were there when St. Anthony was alive. When I was going to these unchanged places, I thought I was going back in time. It’s a landscape that belongs to all times and has no time.

Scope: This is the effect that you have with so many of the Straub-Huillet films shot in natural settings that could be exactly as they looked in the ancient Roman period.

Rodrigues: Yes, some of that same effect. That’s even true of the pagan rituals that Fernando sees. These still go on in that area, with those crazy costumes. They’re called Caretos. They do these rituals around the winter solstice, a kind of initiation for unmarried boys. During these celebrations, they can go crazy and do pretty much whatever they want. When they marry, they can’t belong to the group anymore. I thought they were like Indians in Westerns with their rituals that the white characters don’t understand.

Scope: There’s an overwhelming feeling that this movie is a significant departure from your previous work. This is a movie that’s more concerned with storytelling than it is with dramatic structure. It’s a chain of encounters, the Stations of the Cross. It’s the same structure as a picaresque, with chapter breaks marked by your extended dissolves. You seemed to immerse yourself more this time in the act of storytelling.

Rodrigues: What interests me is how to make a story move forward. The character radically changes. When we were writing, I had the impression that Fernando wasn’t aware of his changes. Perhaps he has a desire to live a different kind of life or become a different person. You feel that he’s a little annoyed with his lover in his current life, and he has an unspoken desire to lose himself and go somewhere else. He fights off the Chinese women, but he’s also somehow enchanted by their presence and feels ready to be transformed by the nature that surrounds him. The birds see the transformation. Birds are up there, like a supposed God is “up there,” looking down. But also the film goes away from this immense canyon, and moves to a more intimate environment where Fernando is closer to creatures. He’s also closer to becoming someone else, though he’s not aware of the change himself. The viewer is learning bit by bit that something strange is happening to him and that maybe he’s changing his identity.

Scope: Early on, you introduce the idea that Fernando has to take his medications. I thought this was very important. We’re aware that if he doesn’t take his meds, he might die. We worry about his mortality from the start. And it lets us see that he has someone who loves him, as annoying as he may be.

Rodrigues: I added the medications element in a later draft. There had to be a sense that his life was in danger. Also, we know that St. Anthony died of some kind of disease. I didn’t want to stress it very much or say what he’s suffering from. In the end, he throws away the meds because perhaps he’s overcome the disease and saved himself, but he’s also transformed himself. He becomes Super-Ornithologist.

Scope: The casting of Paul Hamy as Fernando is interesting. He’s a French actor, not Portuguese. Yet it’s your voice on the soundtrack. Was his casting as much a case of finding the right physicality and face as anything else?

Rodrigues: I didn’t find an actor in Portugal who I was happy with and desired to film. Something that’s crucial for me is the desire to film an actor or actress. I have to have that desire; it’s almost erotic. The film is a co-production with France, and the French co-producers told me about Paul, whom I didn’t really know very well. I had seen him in smaller roles in a couple of films. He’s actually half-American and half-French, and has a lot of that instinctive approach found in the great American actors like James Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Randolph Scott. He doesn’t depend on words so much, and his role doesn’t involve a lot of words. He has a beautiful voice by the way. It’s a soft voice, in contrast with his body, which is muscular, and kind of like a cowboy. He learned Portuguese and made a huge effort to speak the dialogues naturally in Portuguese. But you can’t learn Portuguese just like that. Because St. Anthony was Portuguese, it didn’t make sense that he spoke with an accent! In the moments when I appear, I shot the scenes with Paul and then with me, so I always had each set of takes, because I wasn’t sure if I wanted to see myself onscreen, and I wasn’t sure if it would work. Once I worked on it with my editor, it came together, and then it followed that I would dub my voice when he spoke. It’s the idea that I’m already inside his body, ready to come out. His body is already inhabited by me, and I’m also inhabited by his body. So it’s sort of like a body double involving both flesh and voice. Most audiences of course don’t know it’s me and don’t recognize my voice. Only at the end do they hear the change. I was happy to fool audiences this way. We got something in the end that I think works. I like the way this happened, because the film is involved in a lot of duplicities, of body doubles—there’s Fernando/Antonio, Jesus/Thomas, the two Chinese women—so it made a lot of sense to do this doubling.

Scope: How aware are you that over the course of your filmography, unlike many other directors, you’ve done your best not to repeat yourself?

Rodrigues: Not only aware: I’m very worried that I might repeat myself. It’s something obsessive in me. I so often see how filmmakers create their own worlds and never get out of them. In a way, I think that’s not creative. But I also think that my films are similar. I don’t look at my films after I’m done with them, but if I do see images from them, I recognize myself in them and I can spot my images. So I do have images that I might return to. But I’m very concerned about not making too comfortable a world to which I can just regularly return. That would be easy for me. This is why I put myself into my films—this time in a more radical way, playing a role in front of the camera. Each one of my films reflects something deeply personal. In this case, I’m retracing a place from which I deviated on my path toward cinema. In a way, I’m following the steps I was taking, but now I’m a different person. And the world changed around me. Each film also reflects where I am at the moment I’m making them. If I were to make O Fantasma (2000) now, it would be a different film. Even though the films are generally totally fictions—because I’m very interested in fiction—they also document how I was in each moment of my life when I made them. I like this idea that I see and know myself, and perhaps others will see things in the films that I don’t see. What’s interesting for me about films is how they liberate mysteries.

Robert Koehler