Open Ticket: The Long, Strange Trip of Ulrike Ottinger

By Michael Sicinski

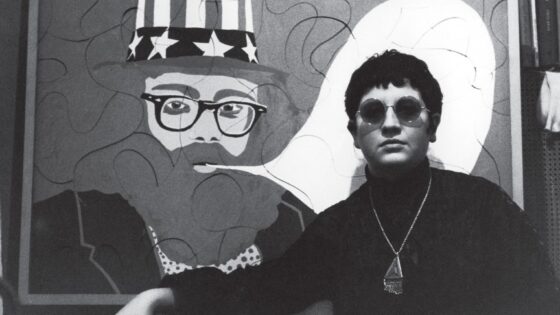

One of the most surprising things about Ulrike Ottinger’s new documentary Paris Calligrammes is how accessible it is. Some cinephiles may be familiar with Ottinger based on an 11-year period of mostly fictional productions that were adjacent to the New German Cinema but, for various reasons, were never entirely subsumed within that rubric. Others are quite possibly more aware of her later work in documentary, in particular her commitment to a radical form of experimental ethnographic cinema. In either case, Ottinger’s films, often difficult to see in the first place, are extremely demanding, in terms of their duration, their bizarre narrative and performance styles, or some combination thereof.

However, Ottinger’s new film is a different sort of animal. It’s biography as intellectual history, and although it explains quite a bit about where Ottinger and her work came from, Paris Calligrammes is also about a much wider milieu of postwar French creativity. It shows why thinking of Ottinger as a German filmmaker, or a feminist and/or queer artist, while not inaccurate, cannot fully explain Ottinger’s overall project. Context is everything, and one of the great benefits of Paris Calligrammes is that it helps us understand Ottinger and her work within a much broader frame.

It’s not often that an artist provides such a thoughtful, comprehensive genealogy of her own creative development. Certain of Agnès Varda’s late works, or select essay films by Godard or Welles, are similarly revealing, if much less linear. Ottinger, quoting Claude Lévi-Strauss, argues that to accurately analyze one’s culture, it is necessary to view it like an outsider. While Paris Calligrammes is unavoidably personal, it avoids sentimentality and hews close to the facts. Ottinger looks at her own history in much the same way that a critic might, providing insights and drawing connections while largely staying out of her own way. She was both participant and witness to major artistic and political upheavals in ’60s Paris, and she takes us through those changes rather systematically.

Paris Calligrammes begins with her arrival in Paris and her discovery of a German expatriate culture centred around Librairie Calligrammes, a Left Bank bookstore and arts space operated by the German expatriate Fritz Picard. It is here that she met various luminaries of the European avant-garde, such as Jean Arp, Hans Richter, Tristan Tzara, and numerous other Dadaists, Surrealists, Lettrists, and Situationists. At this time Ottinger was primarily interested in the plastic arts, and it is here that we begin to understand this filmmaker’s unique, even awkward position with respect to the New German Cinema.

It is one thing to address the fundamental maleness of the New German Cinema, the fact that even the few women of the so-called movement, such as Helke Sander or Helma Sanders-Brahms, have tended to be treated as footnotes to the more emblematic careers of Fassbinder, Herzog, Wenders, and Kluge. But where Ottinger is concerned, we can see that she simply developed as a different kind of artist. Her primary influences were Francophone, many of which were based in literature and especially the visual arts, rather than cinema itself. Although Paris Calligrammes passionately details Ottinger’s days and nights spent at the Cinémathèque française, her cinematic education came later. Paris was above all a place for her to imbibe poetry, theatre, sculpture, and architecture, and this heady atmosphere of the ’60s—the end of Dada up to May ’68, basically—produced a highly unique sensibility.

In this regard, Ottinger has more in common with fellow New German Cinema outliers like Werner Schroeter and Straub-Huillet. Like them, her work is less connected to cinematic genres or the excavation of specifically German historical memory, and more engaged in the relationship between cinema and theatre, the operatic and the mythic. One extended sequence in Paris Calligrammes finds Ottinger discussing the role of the colonial wars in both Algeria and Vietnam within French cultural life, how virtually every artist and intellectual had to take a stand on these issues and incorporate them into their work in some fashion.

What is particularly noteworthy, however, is that Ottinger, thankfully, does not offer us yet another disquisition on the primal cinematic power of The Battle of Algiers (1967). Instead, Paris Calligrammes discusses the impact of Jean Genet’s production of The Screens in 1966. It is here that we can see a fundamental articulation of Ottinger’s artistic and intellectual commitments. She praises Genet’s use of abstraction, his treatment of the Algerian problem as both a hard fact and a broader metaphor, and director Roger Blin’s employment of highly stylized, grotesque costuming and make-up. What Ottinger and so many others found inspiring, and even troubling, about The Screens was the way Genet combined absolute historical specificity and Hegelian master/slave universality in order to show that the French oppression of Algeria was but one iteration of an ongoing Western will to dominate. Where Pontecorvo was didactic, Genet was dialectical and accusatory.

Ottinger herself makes the case in Paris Calligrammes that Genet’s approach was deeply influential for her early cinematic thinking, drawing comparisons to her use of theatrical staging in her early fiction films. But she also identifies a common source for the highly stylized, anti-naturalistic modes of presentation. Part of the intellectual inheritance from the Surrealists was the sense of continuity between the aesthetic and the anthropological study of non-Western cultures, a part of the slippage among the arts and sciences more generally. From Buñuel’s ethnography of cruelty in Las Hurdes (1933) to Jean Painlevé’s macabre science films, Surrealism set the tone for a creative examination of the strangeness of the world. As Ottinger notes, this sensibility was shared by the anthropologists who were fellow travellers to the Surrealist milieu, such as Roger Caillois, Michel Leiris, and Ottinger’s friend Victor Segalen.

If Ottinger has sometimes seemed like an oddball in the history of cinema, it may be worth taking a minute to consider the ethnographic aspect of her filmmaking. For one thing, this particular approach to non-Western cultures—treating them syncretically, engaging with their fundamental Otherness—is deeply unfashionable today, if not politically suspect. White, Western artists are expected to leave subaltern cultures alone, or to at least broach them with the greatest timidity and respect. The Surrealist approach, by contrast, presumes a basic equality among cultures by adopting an ahistorical, synchronic attitude, one that implicitly brackets the privilege of the Western viewer.

Part of the power of the New German Cinema was always its direct interrogation of the authoritarian legacy of the Third Reich, and its implicit argument that this authoritarianism was an outgrowth of a broader tendency within German history, if not the West writ large—a philosophical argument quite familiar from such thinkers as Theodor Adorno and Siegfried Kracauer. Even when a director like Herzog strayed from the strict boundaries of Europe, as in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) or Fitzcarraldo (1982), it was in order to expose the hopeless folly of Western colonialism.

With this in mind, it stands to reason that, for years, Ottinger’s designated canonical work has been the admittedly excellent Ticket of No Return (1979). It is the one of her films that most clearly resembles the productions of the New German Cinema, at least in superficial ways: it mostly takes place in a divided Berlin; it features NGC mainstays Kurt Raab and Volker Spengler in supporting roles; and it has a Peer Raben soundtrack. Perhaps more significantly, Ottinger employs explicitly Brechtian tropes in this film, as her self-destructive woman drinker (Tabea Blumenschein) is consistently followed by a prim chorus of three intellectuals in business attire, each of whom delivers facts and commentary on the problem of alcoholism as it pertains to women in Germany. The women—Orpha Termin as “Accurate Statistics,” Monika von Cube as “Common Sense,” and Schroeter regular Magdalena Montezuma as “Social Issues”—are the stabilizing forces in an essentially plotless romp that at times exhibits the anarchy of Vera Chytilová’s Daisies (1966), but is altogether more nihilistic.

While Ticket of No Return adhered to a European milieu, several of Ottinger’s key works from this period adopted a more Herzogian irony toward the conquest narrative, casting it as a problem specifically imbricated with gender. Between 1978’s Madame X: An Absolute Ruler and 1989’s Joan of Arc of Mongolia, Ottinger established herself as part of an international women’s counter-cinema, highlighted and analyzed in journals such as Camera Obscura and Screen and slotted canonically alongside other women directors such as Chantal Akerman, Yvonne Rainer, and Laura Mulvey.

Ottinger’s work from this 1978-89 period received attention from feminist and queer critics, with most of the analyses focusing on her first large-scale fiction film, Madame X: An Absolute Ruler (co-directed with Tabea Blumenschein). Madame X was notable for its combination of counter-cinematic gestures, overt lesbian sexuality, and jarring use of costuming and pageantry to recode the tropes of nautical piracy and adventurism. As with Ticket of No Return, Ottinger emphasized theme over conventional plotting. Almost the entire first half of Madame X consists of various women in all walks of life receiving the “call” to abandon the boredom of their existence and join Madame X (Blumenschein) on the high seas. Each woman gets her individual vignette in sequence, and once the team is finally assembled, there is only the slightest hint of a mission: the possible conversion of a male foundling.

If one reads contemporaneous reviews of Ottinger’s films of the ’80s, one is struck by the excitement that feminist viewers feel in seeing woman-centred desire reflected onscreen, in a wholly unique cinematic language. (For example, in 1990’s The Woman at the Keyhole, Judith Mayne compares Ticket of No Return to Akerman’s Je tu il elle [1974], arguing that both films accommodate lesbian sexuality, in part, by abandoning classical narrative codes that are themselves cut to the measure of heterosexual desire.) These films are essentially tone poems, organized around broad concepts and loosely connected as though they were a series of outrageous cabaret sketches. One of the things we glean from Paris Calligrammes is that Ottinger’s compositional method was highly intentional and had a very specific historical provenance. From the cut-up methods of the Dadaists to the visually aggressive theatrics of Antonin Artaud (a major influence on Genet), Ottinger was concerned with disruption, iconology, and a form of prelinguistic primitivism that could short-circuit narrative meaning, if not language itself.

We see this in some of Ottinger’s less frequently discussed works, such as Freak Orlando (1981), which is less recognizable as a work of cinema than a piece of filmed theatre, a kind of circus procession in which bearded ladies, little people, men and women on stilts, and various other performers traipse through outdoor locations, only to eventually take possession of a shopping mall, where their presumed freakishness is transmitted by convection onto the seemingly normalized universe of postwar German consumerism. If we address Freak Orlando with the usual tools of cinematic analysis, it falls short. The editing is slack, the framing often seems distracted—the film does not seem directed, in the sense of moving our attention to particular areas and events. But as an Artaudian spectacle, one intended to engulf and devour the spectator’s sense of time and place, Freak Orlando achieves an uncanny instability.

Not only did Joan of Arc of Mongolia conclude this particular cycle of fictional women’s counter-cinema for Ottinger, but it is also the film that decisively pivoted into ethnographic territory, while still encompassing that material within a fictitious, diegetic framework. A film divided nearly in half, Joan of Arc begins with an international group of travellers on the Trans-Siberian railroad, complaining about the dreary emptiness of the landscape outside. Our primary interlocutor is Lady Windermere (Delphine Seyrig), a patrician anthropologist who is continually providing a lofty, detached exegesis on everything we see. (In different circumstances, we’d call it “mansplaining.”) She and the other passengers wax poetic about the glories of Western culture as the light of the world. Meanwhile, Windermere has met a young girl on the train, Giovanna (Inès Sastre), and through behaviour that another passenger wryly refers to as “pedagogical eros,” the older woman is obviously grooming the younger stranger as a potential sexual partner.

Everything changes when the passengers switch lines, from the Trans-Siberian to the Trans-Mongolian, and they are forcibly halted in the middle of the steppe by a tribe in the midst of a potentially violent negotiation. From there, the Westerners become the guests/hostages of the Mongolians, and Ottinger has her non-Western cast perform theatricalized versions of their customary rites and rituals. As Windermere continues to explain everything we see, even going so far as to interpret the Mongolians’ own actions to them, Joan of Arc is ultimately a film about arrogance and misunderstanding. A German tourist (Irm Hermann), for example, is the ultimate Karen, always on the verge of offending her hosts with some crass, thoughtless gesture. And even at the conclusion, when most of the passengers are welcomed into the Mongolians’ religious dance, Windermere sits back, preferring to sketch and observe.

If Ottinger’s films had been a touchstone for academic feminists up to this point, Joan of Arc may well have disenchanted some early champions. It’s a film that highlights the blinkered Eurocentrism of artists and intellectuals, showing that race and class are much more likely to determine one’s worldview than gender or sexuality. Ottinger’s refusal to posit a (white) lesbian utopia, and her pointed if comic staging of a confrontation between radically different cultures may have seemed like talking out of school in 1989, but today it seems fairly prescient of discussions around intersectionality. This film has aged like fine wine.

As I noted above, in Joan of Arc Ottinger literally moves from Western to Eastern diegesis by switching tracks. But it’s not as though the move toward ethnography represented an abandonment of gender considerations. If anything, Ottinger’s cinematic thinking about gender and sexuality offered strategies for avoiding the conventional traps of Western ethnography, that haughty perspective so acutely depicted by Seyrig’s character. In her recent essay on the filmmaker, Sam Bodrojan astutely identifies a camp sensibility within Ottinger’s approach to non-Western pageantry and spectacle. She writes, “Ottinger’s films involve a cornucopia of lavish costume designs and ironic digressions, all in the name of absurd self-expression. This same lens, which guides her vision of a gloriously independent femininity, also suggests that ‘claiming’ another culture is impossible.” By this logic, the two “tracks” are, in reality, part of the same railroad, if you will.

It is difficult to say whether late-’80s audiences were thrown off by Ottinger’s move into the representation of global cultures. What Paris Calligrammes reminds us, however, is that Ottinger’s presence in ’60s Paris infused her work with very specific intellectual components: the anthropological, the ethnographic, the Theatre of Cruelty, the faith that art and cultural knowledge are fully coextensive. This is vital to understanding not only the films that first garnered attention for Ottinger, but especially the later phases of her career. About the time many academic feminist critics had moved away from Ottinger and toward analyses of more conventional narrative films, a new group of cinephiles discovered her through these newer films, which not only explored other cultures but also the conventions of representing non-Western peoples through cinema.

If Ticket of No Return is the consensus masterwork of Ottinger’s first phase, then its equal in her second phase must surely be Taiga (1992), the eight-hour documentary that Ottinger made over the course of five seasons spent with the Darkhad and Soyon Uriyanghai peoples of northern Mongolia. Made during a time when the very nature of ethnography and ethnographic cinema was being reconsidered, Taiga is both a formalist exercise in concentrated looking and a visual example of what Clifford Geertz called “thick description.” Each passage of the film allows a particular aspect of northern Mongolian life to unfold in long, largely unbroken shots. Ottinger alternates between tightly choreographed camera manoeuvres, such as circular tracking shots across the landscape, and careful reframing of objects and events in accordance with their own natural motion and temporal development.

Taiga shows life on the rugged landscape as alternating between patient, organic activity—farming, sheep herding—and more concentrated spans of time devoted to shamanic rituals and other cultural activities. Within the space of Darkhad yurts, Ottinger shows us a wedding, with songs, gifts, and blessings. Later, we see a good-natured wrestling match. We travel with nomads across unforgiving terrain. All the while, Ottinger’s camera maintains a sort of second-person distance from her subjects, keeping them close to her without ever invading their space. They fully acknowledge her presence, but do not try to bring her into their lifeworld. Instead, Taiga creates a tight frame around its subjects that dramatizes their own sense of performance—not only their awareness of being filmed and seen, but also their own distinction between ritual and quotidian actions, the material and the spiritual.

It would be easy to assign Taiga a place in the growing canon of “slow cinema,” not only because of its daunting length, but also because of Ottinger’s expansive approach to temporality. Still, it would really make more sense to consider the film as a key text of experimental documentary, an ethnographic intervention clearly in dialogue with the films of Robert Gardner, Trinh T. Minh-ha, and Chantal Akerman. And in many ways, Taiga looks ahead to certain aspects of the New Chinese Documentary, especially the work of Wang Bing.

Not all of Ottinger’s “foreign engagements” have been as productive as Taiga, but all have been compelling in their own right. These films remain grounded in Ottinger’s belief in exploring Otherness as an opportunity for symbolized thought and confrontation with uncanny new sign-systems. While conventional Western documentary demands that such cultures be authoritatively explained, and identity-based liberalism expects that we merely shrug our shoulders at the impossibility of full understanding, Ottinger calls on the old Surrealists to try to immerse oneself in difference in the hope of experiencing radical self-loss.

More recent work, such as The Korean Wedding Chest (2009) and Under Snow (2011), has broached Eastern cultures, adopting a combination of documentary and fictional strategies. While Wedding Chest is explicit in its examination of the collision of ancient traditions with contemporary modernity, Under Snow thematizes this crisis as a function of its textual organization. In a sense, these are works that could be understood as Ottinger finding her own way to recentre the syncretic concerns of Leiris and Segalen, bringing them into dialogue with current cultural politics. Instead of adopting a Western perspective toward Eastern ritual, Ottinger looks closely at how young people in Japan and South Korea today make sense of older traditions, using them for their own purposes and contextualizing them within their modern lives.

Under Snow, for example, uses a dramatization of Suzuki Bokushi’s Snow Country Tales as a fictional framework for examining the contemporary practices of people living in Echigo, Japan. We see women making decorative crêpe paper, a wedding ritual, and other local activities, as if we were following the sojourn of the two student travellers, Takeo and Mako, from Suzuki’s text. In this manner, Ottinger not only displays the significance of kabuki performance for Echigo cultural life, but also underscores the performative character of all ethnographic gestures. What’s more, the film is overlaid with an explanatory narrative voice that, in this context, melds the documentary “voice of God” with the benshi of Japanese cinematic history.

In one sense, it is unexpected that, after all of her intellectual and physical travels, Ulrike Ottinger would somehow “come back home” to Europe, producing what amounts to an auto-ethnography. But with Paris Calligrammes, the filmmaker has simply shifted forms again, adopting a seemingly straightforward articulation of historical facts in order to expose what perhaps should have been clear all along. Like Artaud and the Dadaists, and very much like the non-Western creative artisans who so inspired them, Ottinger herself is a syncretic production, one whose art has continually answered to multiple theories, instincts, and desires. Like her paintings—which are shown in Paris Calligrammes and are themselves revelatory—Ottinger’s cinema is made of individual icons of significance which can be juxtaposed, rearranged, and pulled apart, all forming radical new stories as they face each other across the lacunae of time.

Michael Sicinski