Journey to the Centre of the Earth: Fern Silva’s Itinerary

By Michael Sicinski

Fern Silva’s films cannot be described as ethnography, personal/mythopoeic film, or essay filmmaking, although they often partake of all of those modes. Though his films are rooted in particular places and cultural spheres, they assiduously avoid the rhetorical or declarative traps of typical nonfiction filmmaking. Instead, they envelop the viewer in a diffuse but concrete ambiance, conveying the palpability of land and water, the weight of the air surrounding hills and trees. They represent a doubled physicality—the world as unavoidably there, inseparable from the cinematic substrate of 16mm filmmaking itself—and the result is a hybridized form of documentary “fiction,” in the classical Latin sense. Silva’s films are made, formed in the interface between reality and those human and mechanical processes that bring it into being.

Fittingly enough, Silva’s feature debut, Rock Bottom Riser, is about natural events and human interventions, about historical and contemporary ruptures that have happened, will happen, or must be avoided. The film is about Hawaii and its long tradition of scientific and spiritual inquiry, and takes as its central point of conflict the Thirty Meter Telescope, a proposed interstellar observatory on the mountain of Mauna Kea. Not only is Mauna Kea one of the most sacred sites in Hawaiian cosmology, but it is also a flashpoint of America’s colonial dominance over the island. Building on this site poses environmental risks, and further threatens protected lands that have already been compromised. As with other proposed public/private initiatives like the Keystone pipeline, the governmental institutions behind the telescope plan are connected to the long-term commercialization of Hawaii, the destruction of its landscape, and the marginalization of its Indigenous communities in the name of neoliberal “progress.”

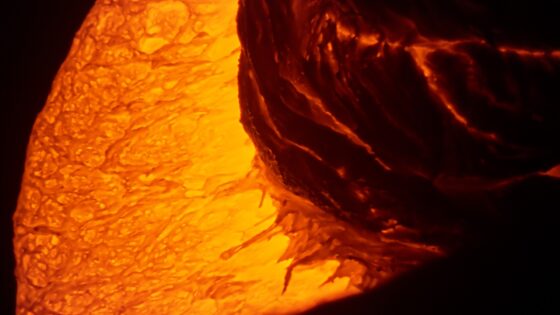

Silva includes the voices of a great many participants in this struggle, clarifying the degree to which a single public works project represents the latest example of a long history of Western aggression and expropriation. However, a scene near the start of the film—an aerial shot zooming in on a river of lava issuing from the Kilauea volcano—clues us in to the existence of another important voice, that of the earth itself. In purely cinematic terms, this sequence is piercing, with hot yellow-orange molten rock forming a river alongside a geothermal plant. We see bubbling lava as it hits certain immovable crags and solidifies, becoming ashen igneous rock. This volcano, which is used as a visual refrain throughout the film, tells us many things about the battle for control of Hawaii—most notably that the island-state is still evolving, a work in progress, born of millions of years of geological activity. Anyone who thinks the landscape is merely there for the taking is deluded, willfully ignoring the accretion of history that can make its way to the surface without warning.

At its heart, Rock Bottom Riser is a film about competing knowledges. We hear the words of Christian missionaries, academics and activists, theatrical performers and historians, and are shown the various acts and objects that seek to establish one’s place in the universe, from the inner workings of telescopes to intricate traditional feather capes (made by Rick San Nicolas, who is currently working as a costume designer for an upcoming Robert Zemeckis film starring Dwayne Johnson as King Kamehameha). We hear the words of leading astronomers such as Frank Marchis of the SETI Institute, which are placed alongside those of men like Nainoa Thompson, who navigated his canoe from Hawaii to Tahiti entirely without the use of Western instruments, relying on traditional Hawaiian understandings of astronomy and oceanography. It is the listener’s job to evaluate the different assertions in the film based only on their persuasive force.

If Rock Bottom Riser represents a shift in Silva’s filmmaking, it is not because of a sudden embrace of documentary rhetoric. Rather, the new film juxtaposes the ideas and experiences of others in much the same way Silva’s earlier films combined potentially conflicting image and sound sets, breaking given cultural spheres apart and poetically reassembling them as competing temporalities. Walter Benjamin spoke of “dialectical images,” particular historical arrangements whose complexity could reveal the thick archaeological history that led to their present dispensation. This, I think, is as close as I can come to offering a satisfactory description of Silva’s films. By showing us a collage of discontinuous moments from a given lifeworld, Silva expresses the density of any given social formation, its atmospheric pervasiveness and resonance. As such, his films show us things that serve to emphasize just how much we cannot know.

Since the start of his career, Silva has always been concerned with organizing our knowledge into these kinds of dialectical images, looking at people and places not to define them but to consider their intriguing lack of transparency. He studied at both the Massachusetts College of Art and Bard College, two institutions with deep roots in the avant-garde. MassArt’s film program was headed for nearly four decades by Super 8 guru Saul Levine, and, during Silva’s tenure there, the faculty included the late Mark LaPore, whose most significant films redefined experimental cinema’s relationship with documentary generally, and ethnography in particular—a project that one sees expanded upon in Silva’s own films. Like LaPore before him, Silva assays the world as a transnational artist; however, as an American with strong ties to his Portuguese heritage, the concept of comparative cultural meaning is not a theoretical problem, but an outgrowth of his own experience.

In his earliest films, Silva articulates the tensions that will define his work: How does the filmmaker avert false claims to objectivity, while at the same time permitting the larger world to assert itself not as personal symbology, but as a set of social and historical forces that can reorient the individual behind the camera? Seldom declarative, Silva employs an associative montage of sound and image that results in films that abjure documentary convention, gently engulfing the viewer with their tactile and affective strategies as they hover between a first- and third-person mode of address. Pitched somewhere between an autobiographical diary film and an anthropological study of Catholicism in Portugal, Silva’s debut film Notes from a Bastard Child (2007) features titles scratched in celluloid, and is partly held together by subtitled narration that combines historical and mythical data. We see scenes that are obviously personal, alternating with the kind of sights that might capture the attention of a tourist: old cemeteries, imposing Jesus statues, and picturesque vistas where Portugal’s Romanesque church architecture is laid out for full appreciation. (The title suggests the influence of Levine, who is known for his many “Notes” films.)

Located somewhere between ethnography and collective portraiture, Silva’s second film, Spinners (2008), is as close to a straightforward documentary as he has ever made, a depiction of adults’ night at a New Jersey roller rink that observes a host of seniors displaying their remarkable skills on wheels. Soon after this, however, Silva travelled to new lands, camera in tow, and began refining his cinematic interest in cultures not his own. After Marks (2008) represents Silva’s most direct engagement with LaPore’s cinema—as the title suggests, being “after Mark” entails learning to live with the faded scars of old wounds. Containing some of Silva’s best handheld cinematography, the film is shot throughout India, ending in Goa, a southwestern state in India whose culture still bears the traces of its colonial past as a satellite of Portugal. Sahara Mosaic (2009) is perhaps Silva’s most overtly conceptual film from this period, evincing a critical stance that would re-emerge in his later work following his flirtation with a more abstract, impressionistic approach. Here, Silva juxtaposes place and habitus against commodification and stereotype, using deft editing to compare scenes of Morocco with the faux-global illusions of Las Vegas. Capturing the sights and sounds of bustling streets, traffic jams, and daily commerce just two years before the collapse of the Mubarak regime and the Tahrir Square uprisings, Silva communicates the ordinary joys and hassles of daily life and contrasts them with the faux-Arabia of Vegas hotels like the Luxor and the Sahara. By “learning from Las Vegas,” as it were, Sahara Mosaic engages with tourism as colonialism by other means—a comedy of misunderstanding.

Silva’s next two films again reflect his oscillation in this period between personal history as a ground zero for broader exploration and a more diffuse, intellectual form of assemblage. In Servants of Mercy (2010) Silva returns to Portugal, building outward from a cinematic portrait of a man who once worked for his family to examine the ongoing development of the nation, the gradual decline of one bourgeois European order, and the consolidation of global capital; as a conceptual refrain, Silva uses Fernando Pessoa’s 1934 poem “Portuguese Sea,” which laments the human cost of taming the ocean, and the loss of a culture’s deeper connection with the natural world.

Servants of Mercy was followed that same year by one of Silva’s signature works: made in Brazil, In the Absence of Light is a mini-epic that examines human and animal experience at multiple levels of abstraction. We see both positive and negative images, underscoring the sense that the realm we are observing is not entirely formed and still coming into being. We see images from Carnaval in Bahia—anchored by large balloons stamped with the logo for Bradesco, one of Brazil’s biggest international banks—but we also see life on the jungle periphery: bonfires illuminating the darkness, small coastal bars and locales, the struggle of newborn turtles scrambling from the beach into the ocean. Silva’s careful, dialectical editing shows us two conventional ideas of Brazil—urban debauchery vs. the rainforest—but also, and most importantly, the official management that negotiates the interstices between these zones. The images of men with Geiger counters and agribusiness workers spraying pesticides alert us that Brazil is a state with no purely cultural or natural contours; everything is very much under control.

Although In the Absence of Light has its personal aspects—Silva, as a Portuguese-American, has a certain unavoidable relationship to Brazil’s colonial past—this is the film in which the subjective element in Silva’s work is fully incorporated into a total way of seeing, one not bound to individual history or biography. From here, Silva no longer emphasizes the struggle to avoid the traps of ethnography, or to situate one’s position with respect to personal identity or the history of transcultural representation; instead, he approaches his subject matter as an artist who understands his place with respect to things. This is not to say that his filmmaking has become systematic: rather, the sensitivity and doubt that had previously defined his work are now simply a part of his artistic personality, readily apparent in his handheld images, combination of environmental and contrapuntal sounds, and approach to editing that avoids easy comparisons in favour of gradually accumulating insights, offered for the viewer’s own cognitive mapping.

Passage Upon the Plume (2011) is a relatively short film, one that gains its strength through a relaxed formal tension. Filmed largely in Cappadocia, Turkey—a mountain region known for the daily launch of scores of hot-air balloons—with additional footage shot in Egypt, the film weds images of interiors, street scenes, and buildings surrounded by scaffolding to extreme long shots of the balloons of Cappadocia. Here, Silva offers a study in disparities of scale and cinema’s unique way of altering foreground/background relationships: the rounded forms of the balloons play against the mountains, which in turn ricochet off the more linear, organized forms of urban Egypt. Though Passage borrows some strategies from Sahara Mosaic, the poetic effect is quite different: Wallace Stevens as opposed to Bertolt Brecht.

Shot in Haiti in November 2010, just under a year after the catastrophic earthquake, Peril of the Antilles (2011) unsurprisingly captures the nation at a crisis point; a rising cholera epidemic, partly the result of a completely destroyed national infrastructure, would itself soon be exacerbated by the devastation of Hurricane Tomas later in the month. The film depicts vast, angry skies with violent clouds on the horizon, winds whipping against already precarious shelters, and forests helplessly poised against the approaching weather. Silva, who was in Haiti to visit a friend, intercuts these portentous images with degraded video of people hanging out and having fun, a flashback to everyday life in a country that had been deprived of the reassurance of the ordinary.

A dense mini-epic, Concrete Parlay (2012)—at 18 minutes, Silva’s longest film until Rock Bottom Riser—both mocks and exemplifies the spatial prerogatives of the jet set, using an undulating “magic” carpet as its organizing image to consider the thrill of flight along with the ideological “baggage” implicit in tourism. But the film also grapples with the filmmaker’s freedom to bring the distant closer—both in terms of capturing images and sounds from far away for cinematic circulation, and of the unique capacities of editing, which can weld together footage from places that, while distant from each other spatially, are connected by the often-invisible ley lines of capitalism and colonial history. An astute viewer of Silva’s films would probably notice the influence of Warren Sonbert, a filmmaker of remarkable vision, wit, and self-effacement whose attitude to the world around him was perhaps best summed up by the title of his 1989 film Friendly Witness. In its images of unexplained religious rituals, the stark, unburdened gaze of a blackbird, the digital display of a flight simulator, church walls covered with medieval icons, mountain vistas and city streets, all undergirded by a complex audio mix of natural and musical sounds, Concrete Parlay practically sings with Sonbertian cosmopolitanism, even as it revels in Silva’s own preoccupations: the necessity of bringing the big world into dialogue with itself, observing affinities but never flattening cultural and historical specificity.

While Silva’s next three films are much less ambitious than Concrete Parlay, they similarly engage with questions of travel and movement, culture as lived vs. culture as stereotyped for outside consumption. A short travelogue documenting a road trip through the southwestern US, Tender Feet (2013) recalls such Bruce Baillie ethno-journey films as Quixote (1965) and Valentin de las Sierras (1971), inasmuch as it stipulates a kind of quest (in Silva’s case, physical evidence of the impending apocalypse, as prophesied by the Mayan calendar) that can never be fulfilled. The title is a joke at Silva’s own expense: whereas previous travellers earned callouses by trudging through this landscape, the filmmaker moves by car down the highway, experiencing a West that was long ago “won.”

Continuing Tender Feet’s comparatively local approach by bringing a global perspective to bear on the filmmaker’s own country, Wayward Fronds (2014)—a tragicomic portrait of the state of Florida, a part of the US that often defines itself through frontier mythology and wild-man posturing—is in some respects an extension of Sahara Mosaic’s bemused examination of a nation in relative infancy working overtime to generate its own mythologies. From its very title, Wayward Fronds suggests a nature that has asserted itself beyond the desired parameters of those who own it: the presence of Disney World only points up the state’s endless battle against its primeval identity, the unruly wilderness that always requires pruning, clearing out, and cutting back. The film depicts Florida mostly as it is: airboat trips across the Everglades, workers hacking their way through the thicket with machetes, as well as the working-class kitsch of Weeki Wachi Springs, home of the chintzy “mermaid shows” in which underpaid young women cavort in glass tanks with their legs bound by nylon “tails.” It’s hardly surprising that Silva seems far more comfortable levelling direct criticism and bitter irony at his own country: there are things one can always say about one’s own culture that an outsider ought not to, and besides, taking jabs at the US is still punching up. Still, Silva never takes cheap shots, and Wayward Fronds makes a clear distinction between the exploitative economy that produces a sad spectacle like the mermaid show and the folks who are doing their best with the employment available to them.

Made in collaboration with jazz musician Phil Cohran, Scales in the Spectrum of Space (2015) differs notably from Silva’s previous films in terms of its construction, being an assemblage derived from over 70 hours of footage of the city of Chicago provided by the Chicago Film Archive, which commissioned the project. However, it is very much of a piece with the artist’s other work in Silva’s application of his lyrical montage approach to the found footage, juxtaposing iconic events (e.g., long shots of police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic convention) with placid moments from daily life in the city’s South Side and images of Black people cautiously leaving their suburban homes, seemingly uncertain as to whether or not they have truly secured a piece of the American Dream. Echoing certain films of Abigail Child, Scales in the Spectrum of Space is both a dense intellectual montage in sound and image and a consideration of how a city works, consciously or not, to produce an image of itself.

Building directly off Scales, The Watchmen (2017) takes as its subject Illinois’ now-defunct Joliet prison, perhaps best known for being featured in 1980’s The Blues Brothers (a film whose director I refuse to mention by name). Built as a classic Benthamite panopticon (famously articulated by Foucault in Discipline and Punish), its cells architecturally arranged in a circle with a watchtower in the central hub, Joliet is framed by Silva as an unintended monument to the American carceral state even as its structural schema speaks to a modernist conception of the body as a synecdoche of the nation. Prisons are largely privatized now, and, operating under the twin logics of capital and white supremacy—which insist on making unwanted bodies disappear—they serve not to reform or retrain inmates, but simply to segregate them from society. At the end of The Watchmen, Silva stands at the heart of the prison and starts spinning his camera, faster and faster, describing the curved walls of the panopticon; not coincidentally, the flicker and blur of this accelerated image, with flecks of light disrupting the darkness, forms a combination camera obscura and phenakistoscope. Photography and cinema are here merged with the disciplinary state, as two modernist technologies designed to extract meaning from bodies.

Also from 2017, Ride Like Lightning, Crash Like Thunder was Silva’s final film before embarking on the Rock Bottom Riser project. Its title, along with certain of its images (a thunderbolt, an electric chair) suggests a sharp left turn into heavy metal, and this is not completely incorrect. A return of sorts for Silva to the Hudson River region of New York, where the filmmaker’s alma mater Bard College is located, Ride Like Lightning is not explicitly about experimental filmmaker (and Bard professor) Peter Hutton, but shares with Hutton’s work a keen fascination with the Hudson River area, its landscape and shifting seasonal character. Where Hutton’s films tended to be stately affairs—silent, meditative, fixated on the gradual movements of the river and its surroundings—Ride Like Lightning combines images of the region with comical horror imagery: several scenes show a rubber-gloved hand with green skin and claws, an unseen monster preparing to take over both the area and the film itself. (This speaks to Silva’s stated intention of combining the rarefied nature of Hudson River School painting—a significant influence on Hutton’s work—with more popular legends of the region, such as Washington Irving’s tales of Rip Van Winkle and the Headless Horseman.) We also see Silva dunking his celluloid in a bucket of blood-red dye to produce shots of the river that are tinted with an electric orange pallor, as if environmental forces have rendered the world jaundiced and uninhabitable. Ride Like Lightning suggests both a puckish engagement with the legacy of upstate New York landscape cinema (Hutton, Robert Huot, Vincent Grenier) and a subtle criticism of that tradition, considering what it usually excludes.

Although the move from short to feature filmmaking is a significant one for any artist, Silva’s expansion of his time frame in Rock Bottom Riser is an organic development, one occasioned by his continuous furthering of his themes and orientations. A landscape film, a travel document, and an engagement with a culture that is not Silva’s own, Rock Bottom Riser bears formal traces of the early films Silva made in Morocco, Haiti, and India, but also elaborates his more recent cultural histories of pocket regions of the US. While Hawaii is of course an American state, which nominally makes Rock Bottom Riser an “American” film, the island—a space that is crisscrossed with conflicting histories, in which the domestic and the global are ineluctably merged—has more in common with Puerto Rico, a land continually relegated to a twilight zone between state and colony, than with Florida or New York. And like Puerto Rico, Hawaii is historically a multiethnic state, its identity forged through a complex history of colonialism. It has only been American capitalism’s success in redefining Hawaii, turning its culture into a consumable simulacrum—a place for Americans to “get away from it all”—that allows this deeply racist nation to accept Hawaiian otherness.

What Silva shows quite clearly through his oblique strategy of creative nonfiction is that the radical flattening of culture and history on which global capital thrives actually has its limits. The Indigenous activists who object to the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea have successfully blocked its progress for over ten years now, and the matter is not even close to being resolved. The mosaic of voices in Rock Bottom Riser presents a wide array of perspectives on what counts as science, who gets to define Indigenous culture, and whether conservation represents a roadblock to progress or the protection of an ecological patrimony that some refuse to appreciate or understand. But in the end, after all the arguments have long since been silenced, the island’s volcanoes will continue to provide their own answer. From the earth’s core to its surface, Hawaii regenerates itself, writing its own history in molten rock.

Michael Sicinski