Impresión de un cineasta: On the Films of Camilo Restrepo

By Jay Kuehner

The title of Camilo Restrepo’s breakout short film, Impressions of a War (2015), suggests the anomalies inherent in conceiving of a historical portrait of modern Colombia. A war is not typically thought of as something that leaves an impression; rather, it maims, disables, obliterates, defaces, violates. Nor does its legacy register as a mere impression: the cumulative trauma amounts to nothing less than an indelible scar, both corporeal and psychological, that exceeds reason, conciliation, and memory.

What, though, can one make of a war without end? A war among various factions whose ideologies can no longer be morally or politically inferred? A war in which an entire country, according to the film’s opening slate, has been turned into a battlefield, and a sense of generalized violence has gradually yet insidiously settled over the whole of society? Colombia’s history of violence is so fraught as to resist any summative representation or cogent insight, perhaps especially from the distance of a self-imposed exile. Born under the shadow of FARC and the Medellín cartel, Restrepo—a trained painter and staunchly independent filmmaker now working in France—found traces of war in the minutiae of quotidian life. In this context, the question was reframed: Where wasn’t war? Taking the notion of impression as a tactile index of war’s legacy, Restrepo filmed what he could see, the material essence of a conflict writ in the streets, upon bodies, in songs of protest, under the metal shells of taxi cabs, on newsprint wrapped around market-stall fruit, in pixels from soldier’s phones that filmed from the front lines of guerrilla warfare. The devil truly was in the details: here, history was written in the margins, in less conspicuous sites of inscription.

By uncovering the multivalent means of such markings—in Restrepo’s words, alternately “deliberate, accidental, ostensible, fleeting, or dissimulated”—an unlikely portrait of civil resistance emerges. The rejects of daily newspapers, from botched print runs with ink oversaturated or evaporated, their image registration askew, might be symbolic of a dubitable state of official information. The provenance of an inmate’s tattoo is conjugated: from its conception in prison, crudely administered with a janky needle, to signifying the body’s vulnerability, its capacity to endure pain, the will to resistance, and ultimately recovery. A luxury hotel, the former property of an extradited drug lord, is converted by paramilitary groups into a torture chamber, its walls bearing the graphic evidence of such horror. Decades on, villagers attempt to rehabilitate the building, exorcising it of its sordid past by painting over its walls with counternarratives of survival. Somewhere beneath the manicured gardens, the bodies of victims still lie waiting to be exhumed.

Behind each impression a chain of causation can be inferred, the status of the image never neutral. The fabric of Colombia’s convulsively etched history is palimpsestic, like the hotel walls still stained with the vestiges of suffering. The persistence of, and insistence on, materiality reveals seemingly consolidated forms as strata, consisting of layers of competing historical forces: Restrepo’s preferred medium of 16mm film stock stresses the granularity of his aesthetic within a given milieu, yoking the apparatus to its object. The camera too brings its own story to bear upon any attendant evidence. Hand-processing the results, at Paris’ artist-run L’Abominable laboratory, extends the filmmaker’s autonomy and enlists one community toward the realized depiction of others.

Impressions of a War refines (but never polishes) the project Restrepo began with his first two short films, portraits of place that are remapped through alternative modes of representation. In Tropic Pocket (2011), the Colombian territory of Chocó—an area with a high Afro-Colombian and indigenous Emberá population—is visited through different visual itineraries, images sourced from missionaries, soldiers, industry, and villagers themselves. Scrambling its multiple points of view, the film reveals a liminal zone that serves as a riposte to the colonial imagination, just as the Darién Gap in Chocó’s north served as an unbreachable barrier to proselytizing priests. Like Shadows Growing as the Sun Goes Down (2014) locates another marginalized habitat in Medellín, where auto salvagers and street jugglers dwell in a symbolically perpetual midday, a vertical limbo in which no shadow is cast. An acrobat dangling from a corde lisse strapped to a roadside tree, suspended in descent—an image suggestive of both grace and violence—serves as an unforced metaphor for the complexion of Restrepo’s Colombian triptych; no sooner does it register, however, than the acrobat takes a cordial bow and disappears from the frame, continuing her solicitous rounds amid stalled traffic.

If Restrepo’s work to this point evinced a coarse yet stylized reflexivity—not least in its deployment of a sonic arsenal of bullets, saws, drills, telenovelas, sirens, cumbias, and an unwavering voiceover, all encroaching on the image—it hardly portended a quasi-musical as his next project, which saw Restrepo tracing a throughline from Medellín’s songs of punk protest to the maloyan blues of Réunion, a French island in the Indian Ocean of no known indigeneity, its isolation invoking the spectres of colonialism and diasporic identity. (Though in reality, the film was shot in Paris.) Cilaos (2016) takes its title from a mountain town that rests within a volcanic caldera, where fugitive slaves once sought refuge and where a young woman, played by maloyan singer Christine Salem, goes in search of the lost father she never knew, at the behest of her dying mother. The fable-like story is transmitted through staged exchanges in which the daughter meets extended family along the way, only to learn that her father, known colloquially as “La Bouche,” is dead. The ensuing communion of spirits is expressed through ritual song, which begins as a lament and then rises into a frenetic incantation, the father’s vulgar parole finding enunciation in the mouth of his daughter. Part ancestral myth, part minimalist musical, the crypto-poetic Cilaos achieves a sui generis rapture through the slightest of means.

A companion piece to Cilaos, La Bouche (2017) inversely mirrors its predecessor’s familial tragedy in its tale of a father whose daughter has been killed by her husband. An establishing sequence introduces two women framed in frontal exordium, singing in unison: “Wake up. Father, wake up. Your daughter is dead. We know who killed her. You can catch him. He’s nearby.” The refrain, “What will you do?” is scored as a percussive entreaty, meted out on djembe by the father’s sons, who are gradually revealed in a slow tracking shot. The narrative as such proceeds by way of this patent reduction, with the camera oscillating in a hermetically denuded space (the set design consists solely of straw matting on a black backdrop), with the exception of a lyrical, ambiguous passage between father and son that unfolds in the forest. The ambiguity is deliberate, leaving open to interpretation the notion of whether the dead can speak, if solace is a surrogate for vengeance, and if grief passes through the skin of a drum. Lending the tale an even greater sense of gravitas is its grounding in reality, derived as it was from the true-life story of its lead, Guinean percussion master Mohamed “Le Diable Rouge” Bangoura. The drumming finale assumes the weight of grief and expectation, channelled through Bangoura’s hands and then upon his face, the camera fixed on a well of conflicting emotions conjured, sustained, and possibly released through playing. The final impression, beyond one’s utter marvel at Bangoura’s skill, is that Restrepo has here arrived at the most fiercely sincere expression of his work to date.

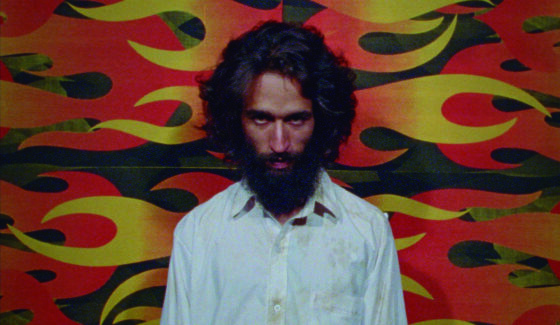

Anticipation was thus understandably high for Restrepo’s first narrative feature, Los Conductos, which premiered in the Berlinale’s new Encounters section and won the festival’s Best First Feature Award. As Restrepo’s films are manifestly cyclical, it’s appropriate that the film should return to certain beginnings: Los Conductos finds Restrepo back on native soil, reuniting with a character who dwelled at the margins of Like Shadows Growing as the Sun Goes Down, in which he was seen throwing stones at empty bottles against the horizon of downtown Medellín. The life of the wiry, barbed Pinky (Luis Felipe Lozano) is here reimagined as the story of a fringe-dwelling addict who flees indoctrination from a cult-like group as he tries to regain his humanity. While inevitably the most expansive of Restrepo’s films to date, the director’s typically lean execution has been honed even further, to almost comical extremes (witness an early scene in which Pinky appears to steal a motorcycle by stoning its driver, depicted in a montage so primitive it would make Bresson blush). The narrative is parsed accordingly, with the bulk of backstory mostly allocated to Pinky’s voiceover, in which he tells of a life endured under the tutelage of a mysterious group whose leader (a.k.a. “Father”) was “our voice and our conscience.” Squatting in an abandoned warehouse while working at a bootleg screen-printing factory, Pinky reflects on the allure of collective inculcation, of “at last living the love we had longed for. But we all knew we had not come to the group for love, but because of our hatred we felt toward society. The sum of all our hatreds, Father turned to a love between us.” Though the unnerving picture evoked by his words is belied by innocuous images of him now hawking counterfeit T-shirts at the mall and lingering over fast food, the memory of violence—evoked through his passing acknowledgement that “We had to close our eyes on our own barbarism”—haunts his quotidian routines, creating an uncanny tension. One such instance involves a power washer, which, used by Pinky to hose the ink from printing screens, is momentarily weaponized against a foe—although the only casualty ends up being a sad pack of drowned cigarettes.

The transmission of energy implied in the cables and conduits of the title seems both electrical and metaphysical, though it is the former that is stripped, stolen, salvaged, and regenerated by a sinister “copper mafia,” for whom Pinky toils as a “little helper.” The sight of a warehouse pillaged of its electricity by nocturnal thieves is a formative memory for Restrepo, who has spoken of attempts to record evidence of such looting at his own father’s property; no sufficiently damning image could be furnished, however, only a document of banality in the form of empty sockets and pallid, crumbling walls. The fate of the image, concluded Restrepo, was either indifferent to or entirely contingent upon the view of its maker, and the genesis of his work appears predicated on staking out what might exist in between or outside of such a proposition. Indeed, Restrepo’s abjuring of conventional storytelling may be a response to the exclusions imposed by overtly objective and subjective perspectives, which Restrepo synthesizes like the coils of copper dispatched to the furnace; matter that must lose its shape to be regenerated. The “perpetual resurrection” spoken of by a retired bandit who shadows the proceedings could well reference the conception of character according to Restrepo, itself more of a continuum inhabited by many identities, a composite of memories and future illusions. Structurally, Los Conductos itself is like a forge in which volatility becomes the rule, where narrative is not so much subject to contingency as it is inherently contingent, exposed to violent convulsions and capricious digressions. Suffice to say, whatever brick dust Pinky is smoking, it’s strong enough for the viewer to catch a contact high: past lives appear to be recalled, conjured without context, images of which may simply seek to regain a little humanity of their own.

Though such an artistic gambit may seem like an indulgence of Colombia’s mid-century Nadaísmo movement (whose poet laureate Gonzalo Arango graces the film’s epilogue), Los Conductos proceeds in a far less nihilistic vein: its particular sense of disillusionment, bordering on the melancholic, is in the service of a more expansive and empathic manner of “relating” to its anti-hero. The plight of Pinky, whose real-life escapades ground the film in biographical precedent, is ultimately a story of survival. That Restrepo has saddled this figure with a host of identities, not all of them easily discernible or compatible, signals a dialectical approach to character formation that holds history to account. The simultaneous evocation and incarnation of Desquite, the legendary bandit from the era of La Violencia in the ’50s, circulates a plausible consideration of diabolical acts committed in similarly volatile habitats, ergo justifiably so. As an agile embodiment of desquite (revenge), gracioso (joker), and diablo cojuelo (lame devil), Pinky traverses a gamut of social and historical conditions as if in immersive inoculation. How else, Los Conductos intimates, can there be stimulation of resistance? Against which backdrop, within what context, is Pinky seen climbing from the depths of a landfill, exiting the frame either in a triumphant tranco (leap) or mired in destitution? Judgment, per illogical convention of the film, can only be withheld. Pinky seems neither cipher nor sacrifice to a cinematic cause, but rather something else: maybe a mascot in a military parade, or an outlaw whose life is inscribed on the handle of a revolver, tossed to the dirt in surrender. An addict stabbed by his dealer, who survives and is reborn, or a labourer who insists in a plaintive tone, “Mister, can you pay me the days I worked? I don’t know anyone here, and I need cash to pay for a room.” He contains multitudes. A visceral proxy for our ills, perhaps, but palpable as the flesh of a tree caught in the teeth of a saw.

Jay Kuehner