Chums at Midnight: On Hopper/Welles

By Alex Ross Perry

Presented as a “new” documentary of which Orson Welles is the credited director, Hopper/Welles is at once less and more than whatever would accurately befit that pithy description. On the one hand, the film is, in fact, 130 minutes of Dennis Hopper, operating in peak mysterious-sage-poet-cinematic-warlord fashion, captured roughly halfway between the production and release of his totemic masterpiece, The Last Movie (1971). As such, it stands in opposition to the scripted/performed L.M. Kit Carson and Lawrence Schiller’s The American Dreamer (1971).

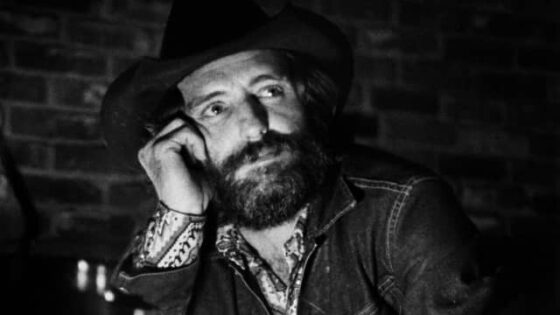

An opening title card establishes “Los Angeles, November 1970,” though it’s unclear when exactly this was filmed in relation to Carson and Schiller’s film, as Hopper looks like he just stepped off its set, and engages in copious familiar pensive beard-stroking. As well, Hopper riffs on one of his most profoundly ridiculous lines from The American Dreamer here: “I’m not queer, but I am a lesbian.” He also doubles down on that film’s schtick that he doesn’t read, further cementing the extent to which he is acting, writing, and essentially doing tried-and-true material in the fictionalized documentary.

In as much as The American Dreamer has long been instrumental in solidifying the Hopper myth of the Taos-dwelling, gun-toting, orgy-hosting maniac whose lifestyle became an extended performance of the themes and characterizations of The Last Movie, the Hopper on camera in Hopper/Welles (and if there is a frame in which Hopper is not on camera, it’s only because his face is obscured by one of the countless slates that punctuate this morass of seemingly unedited footage) is the Hopper who would have been in on the joke of The American Dreamer. Lucid, articulate, and questioning what it means to undertake the godlike act of creating film, this is likely closer to Hopper as he was, not as the public wanted or needed him to be in order to satisfy the destiny promised by Easy Rider (1969).

On the other hand, Hopper/Welles is dubiously not anywhere close to an actualized Orson Welles project. If anybody ought to be credited as the author of this newly resurfaced footage, aside from Filip Jan Rymsza and Bob Murawski, who assembled it in the present, it might as well be Jake Hannaford, the character played on camera by John Huston in The Other Side of the Wind (2018), and off camera here by Welles. This footage was among the discoveries made in the recently completed efforts to release The Other Side of the Wind, which truly begs the question: what else is in there? It’s hard not to imagine Kane’s storage warehouse, but with mountains of reels containing similar ephemera shot on the “set” of The Other Side of the Wind over its multi-year gestation.

Neither Welles nor Hannaford appears onscreen in Hopper/Welles, and the extent to which Welles maintains this performance off camera becomes staggering as the proceedings wear on and the lengths to which the views being expressed as a means of stimulating debate conform to Hannaford, considering that Welles was improvising as a character he himself was not playing in the film for which this footage was ostensibly shot. Welles’ daughter Beatrice says that her father had intended to make a documentary about Hopper, so perhaps this was Orson’s ever-thrifty way of using one film’s budget to finance a dry run for another. It takes no effort to imagine what the two men saw in one another, with Hopper functioning as yet another proxy or onscreen surrogate for Welles, unaware as of this filming that having already made his Citizen Kane (1941) with Easy Rider, that The Last Movie was months away from being his own personal Ambersons-level catastrophe. Welles would likely relate to Hopper’s impending shunning more than his former protégé Peter Bogdanovich’s multiyear run of successful, moneymaking hits.

Confusing, all of it, but this is how Hopper/Welles somehow transforms from mere curiosity into something more befitting the hall of mirrors that The Other Side of the Wind ended up being, and clearly was always intended to be. Watching Hopper/Welles, it’s possible to imagine The Other Side of the Wind not as a film, but as a publicly accessible archive out of which everybody is encouraged to find their own treasures and create a version specific to their curiosity and interests (1,083 reels worth, they say, though of what duration has not been explained, as far as I am aware).

Viewing the film as a traditional documentary interview, as I initially assumed it to be, the absence of Welles’ unmistakable timbre was at first jarring. It took a moment to realize the man elsewhere in the room was the maestro himself, at which point the aural differences seem to be the result of improvisational filmmaking with casual regard for microphone placement. The realization that Hopper is being, at times, aggressively forced to address his beliefs in the power of movies, by a fictional character, comes slowly; you can watch it begin to wear off when, after about an hour, Hopper no longer treats this as an interview and starts referring to Hannaford by name, knowing full well that arguing with the film’s main character would provide better material than continuing to parse The Last Movie in highly specific detail. It cannot be overstated the extent to which the current film known as Hopper/Welles seems to be making use of every single available second of this sit-down: why else would it be 130 minutes rather than, say, a more reasonable 90? However, according to reports, a full five hours was shot. Yet absent is even a tossed-off line where Welles breaks character, gives Hopper anything resembling direction, or shatters the illusion. Slates aside, this creates more of an unbroken immersive experience.

This is, to my knowledge, the first time that anything so stridently resembling raw footage has been packaged and assembled as a commercially available film, even though it is being marketed as a straightforward documentary. As the effect wears on—and wears thin, it must be said—it becomes hard to deny that what we are watching does in fact rest comfortably somewhere between the reckless form-breaking Welles was attempting with The Other Side of the Wind and would successfully actualize with F for Fake (1973) and the Warhol-approved film-as-art-project leanings of Hopper at this exact moment. The downside to this footage-dump approach is that it robs Hopper/Welles of any potential to be the digestible My Dinner with Andre (1981) for the cinema-freak set. There is “for the die-hards only” and then there is this, which, after a while, borders on Warholian endurance challenge cinema, despite being breezy, humorous, and gorgeous to behold: the starker than stark black-and-white photography by Gary Graver is a master class in minimalism as aesthetic choice, and though I cannot find confirmation, the aspect ratio, deftness of camera movement, and duration of each roll would suggest this to be Kodak Tri-X or some comparable 16mm stock.

It’s undeniable that what we get of Welles here is preferable to the bitchy, insulting, court-holding luncheon master of Henry Jaglom’s recent book of interview transcriptions My Lunches with Orson. The Antonioni-bashing that “Hannaford” confronts Hopper with is in line with the obvious parody of such lugubrious European art-film ennui in The Other Side of the Wind; whether or not this is precisely what Welles himself thought is beside the point. One jewel is Hopper’s claim that he bought a ticket for L’avventura (1960) seven times and hasn’t yet seen it because every time he fell asleep, admirable if only for it’s unpretentious relatability. He doesn’t fault the film: Hopper is so enthusiastic and genial about nearly every film or director that comes up, waxing especially poetic on Buñuel, that Welles/Hannaford demands to know, “What don’t you like? I want you to rage against something!”

The true Welles breaks through only when Hopper compares the effect of watching a movie being filmed by the locals, soon to be left abandoned by Hollywood, in The Last Movie, to magic. It is here that the lifelong magician, a few years prior to F for Fake, imbues Hannaford with pure Wellesian logic, arguing “all that we can ever do in a movie is to draw on these mystical first sources using the crappy little machines. All we’ve been able to come up with in 50 years,” and demanding to know “what movie has ever moved anyone?” The descriptions of the magical power of the movie camera are of interest, as Hopper has clearly been trying to figure this out throughout the production of The Last Movie. Of course this recalls the indelible image of the wicker-woven camera made by said locals, perhaps a better weapon for harnessing the first sources Welles/Hannaford so deeply respects. Hopper doesn’t mention it.

Instead, in this portion of the conversation Hopper drops two of the most literal kernels of insight I have ever heard him offer regarding that film: first, that his largely silent and passive character, Kansas, is the kind of guy who thinks “he wants a ski resort, a 100-room hotel with eight pools” and, second, that the film being shot is titled Billy and Rose, which if it appears on a slate in The Last Movie is a detail I have not retained. He offers that he shot 40 hours of footage for The Last Movie, as opposed to Easy Rider’s 35; when I say that this is for die-hards only, I think of the excitement I felt upon learning these things, as well as not being bothered by the sound of film audibly running through a camera for over two hours, as the best examples of the extent to which one’s mileage may vary.

If Hopper/Welles rests comfortably, albeit accidentally, within any cinematic tradition, it’s less a gonzo Hitchcock/Truffaut and more what Anthology Film Archives curated in 2011 when they presented “Talking Head,” a series of films considering the cinematic possibilities of nothing more than a filmed conversation with, mostly, a single person. It was here that I finally saw Jean Eustache’s Numéro zéro (1971); the series also featured the likes of Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967), Scorsese’s Italianamerican (1974) and American Boy (1978), as well as several of the films in which Claude Lanzmann repurposed untold leagues of Shoah (1985) footage to create, among others, Sobibór, 14 octobre, 1943, 16 heures (2001) and The Karski Report (2010). Lanzmann’s returning to his archives is perhaps closest in spirit, if not content, to Hopper/Welles. This film would be truly at home among these varied works, maybe even more so than alongside The Other Side of the Wind. Without trying to or being aware of the trope, Welles has belatedly made his mark on the subgenre.

Towards the end, Hopper pontificates in his undeniably Manson-esque way about some vague revolution or revolutions he suspects may be imminent. He talks about his ability to retreat to the mountains where he lives, and says at one point, “If they had news on television all day long, I would love it.” It’s hard not to wonder if the eventual realization of this wish and the horrors that came with it is what caused Hopper’s politics to skew conservative in his later years. Watching Hopper/Welles today, where the prophesized revolutions have come time and time again, and this sort of single-performer/single-location shoot is perhaps the safest and most logical option for returning to film production, it does seem clear that we could have worse role models to look to. The recklessness and freedom on display from both performers, here and in their chronologically adjacent work, was an effort to push boundaries away from binary forms of film production; of course, both were mightily punished for their experimentation. What to make of the fact that the table scraps of two geniuses would age over half a century into a piece of work more challenging and frustrating than much of contemporary cinema? Early in the film, Hopper points out, “Movies are made on set, but they’re remade in the editing room.” This holds true for The Other Side of the Wind and The Last Movie; defiantly less so for Hopper/Welles, but sometimes what you get on set is good enough.

Alex Ross Perry