A Pierce of the Action: On Claudine and Uptight

By Andrew Tracy

In his Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes identified two elements at work in the act of viewing photographs. On one level was what he labelled the studium, which he defines as a sympathetic interest on the part of the viewer, “a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment, but without special acuity…To recognize the studium is inevitably to encounter the photographer’s intentions, to approve or disapprove of them, but always to understand them, for culture (from which the studium derives) is a contract between creators and consumers.” The second level of engagement he called the punctum, “that element which will break (or punctuate) the studium. This time it is not I who seek it out (as I invest the field of the studium with my sovereign consciousness), it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me.”

Barthes defined the punctum as an accident, an unpredicted and uncontrollable element within the photographic scene, which means that, strictly speaking, the term cannot be ported directly over into the realm of narrative cinema: theoretically, a filmmaker could rephotograph an image or a scene endlessly until they achieved their desired effect. But if intentionality belies the punctum’s inherently accidental nature, in its sensorial or emotional affect a scene in a narrative film can still yield that unexpected element that suddenly arrests us, and offers us a deeper access into the (hi)stories depicted.

I was reminded of Barthes’ concept of the punctum while thinking of two films I saw over the course of the last year—two long-unavailable films about contemporary Black life, both directed by white men, and both of which are enjoying an ongoing rediscovery. Relocating Liam O’Flaherty’s venerable novel (and John Ford’s 1935 film) The Informer from Ireland in the aftermath of the 1920s Civil War to Cleveland’s Black militant underground in the days just after Martin Luther King’s assassination, Uptight (1968) was released on DVD and Blu-ray by Olive Films in 2012, subsequently screened in the Locarno Film Festival’s Black Light retrospective program in 2019, and enjoyed a streaming run on the Criterion Channel that same year. Criterion also had a hand in the new restoration of Claudine (1974), a remarkable comedy-drama about a Black working mother of six (Diahann Carroll) finding approaching-middle-age love with a charming sanitation worker (James Earl Jones), which screened in this year’s Venice Classics line-up prior to its DVD/Blu-ray release in October.

More specifically, that Barthesian tidbit came to mind as I pondered over a scene from each film that, as per Rollie, had “pierced” me, though more with a sense of exhilaration than pain. Early in Uptight, police searching for a member of a Black militant cell who has recently robbed an arms warehouse pull up in an alley behind a tenement, whose residents line the fire escapes, watching as the cops pick out the fugitive with their searchlights. As some of the officers charge after their quarry, pushing forcefully through the hostile audience on the narrow walkways, the viewers become actors, hurling bottles on the cowering cops below in a stunning silver rain. The scene from Claudine comes right at the end, when Jones’ Roop, who has just tied the knot with Carroll’s Claudine in a wedding ceremony in the latter’s overcrowded apartment, is bundled into a paddy wagon in a chaotic round-up following a clash between police and Black protestors (including Claudine’s rebellious eldest son). Pushing past the cordon of cops, Claudine defiantly joins Roop in custody as the van pulls away, and her six children come running after, jumping aboard with beaming smiles as Gladys Knight & the Pips’ exuberant “Make Yours a Happy Home” carries them through the end-credits roll.

For me, both of these scenes, in their very different ways, exemplify that feeling of shock, of spontaneity, of Barthes’ punctum. They are moments that, without truly breaking from the fundamentally realistic narratives of which they are a part—or rather that assortment of unspoken, contractually agreed-upon signifiers that constitute “realism” for filmmakers and viewers both—nevertheless propel the films beyond a surface fidelity to the real. One of the roles that realism has played in the cinema has been to open a window on life, including those lives we may not otherwise have seen—or, rather, “we,” i.e., the overwhelmingly white and male viewers (guilty on both counts) whose tastes have helped shape the discourse of mainstream cinema. This is why it has so often been a primary mode of films made by and/or about marginalized groups, as to tell these stories is to deliver an inherent rebuke to the codes, conventions, and norms of the mainstream-cinema brand of realism that has traditionally effaced such stories.

But another of realism’s potential powers has been to surprise us, to jar us, disturb us, to use the textures and tonalities of the real to present us with something more than life—to criticize life by creating or revealing something that life cannot or has not. The spontaneity captured in these scenes from Uptight and Claudine is one of defiance (which Barthes identified as the essence of the punctum)—not only a defiance of (white) authority, but a defiance of impossibility, of the seemingly immovable, indestructible edifice of that authority. If anger and violence are the dramatic engines of the bottle barrage in Uptight, the visually expressionistic spectacle of the act propels it into the liberatory realm of the carnivalesque, the temporary inversion of hierarchies wherein the low are made high (here quite literally). In Claudine that inversion is even more extraordinary, as the heroine and her family transform their own arrests into an expression of devotion, solidarity, and joy, a triumphant emotional catharsis that continues through the final shot that immediately follows, of the now-released Claudine, Roop, and the kids walking arm in arm down the sidewalk, smiling and laughing.

Judith Crist, in an otherwise positive review in New York, derided this conclusion as “farcical and easy,” a feel-good falsity tacked on to an otherwise commendably realist slice-of-life. But it is the fact, and the filmmakers’ obvious knowledge of the fact, that this joy is paradoxically founded upon the bitter and tragic irony that people of colour are never safe from the police—even in their own homes, even in the middle of one of society’s central rituals—that gives it such a powerful affective charge. Realism is the vehicle of Claudine as it is of Uptight, but both in their respective ways refuse to adhere to the seamless, sober, “serious” kind of realism that is so often expected of non-genre American films about Black people. At their moments of the harshest, most vivid reality—the reality of invasion, of oppression, of everyday violence in Black people’s lives—these films forego the fatalism that so often rides shotgun with realism.

As much as their style, there was also a certain “impurity” at work in the genesis of both films. While both the production dates and the subject matter of Uptight and Claudine locate them squarely within the era of the late ’60s–early ’70s New Left (as well as Hollywood’s attempts to capitalize on this audience of new, radicalized young viewers), their major creative personnel were members of two older generations of left-wing activism. The first was a white, West Coast cohort whose political consciousness was shaped by the Popular Front of the ’30s, the fight against fascism, and the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s, represented most prominently by Uptight’s producer-director Jules Dassin and Claudine director John Berry and producer Hannah Weinstein. Both Dassin and Berry had worked their way up the Hollywood studio ranks in the ’40s, moving from programmers to stylish noirs—Dassin with Brute Force (1947), The Naked City (1948), Thieves’ Highway (1949), and Night and the City (1950), Berry with the less-celebrated Tension (1949) and He Ran All the Way (1951)—before their leftist sympathies forced them into exile during the blacklist era. Weinstein, conversely, only moved into filmmaking after her Red Scare-induced exile, following a quarter-century career as a journalist, political organizer, and speechwriter. Putting down roots in London in 1952, she used seed money from the US Communist Party to found the television production company Sapphire Films, which launched such successful syndicated series as the Richard Greene-starring The Adventures of Robin Hood and became a haven for pseudonymous blacklist victims, such as Weinstein’s former writing partner Ring Lardner, Jr.

The second generation was a slightly later one comprised of African-American, predominantly East Coast-based artists and activists, connected to the internationalist progressivism of that earlier group but also espousing the development of a distinctly Black art and culture as a weapon in the struggle. On Uptight, this circle was represented by its co-stars and co-writers Ruby Dee (who had apprenticed at the American Negro Theater, one of the epicentres of this movement, before moving into films in the ’50s) and Julian Mayfield, a New York-based playwright, actor, and novelist who had become a target of FBI surveillance for suspected Soviet sympathies, and had gone into exile in Ghana in the early ’60s. On Claudine, that link was provided by Dee’s husband Ossie Davis, who in 1971 partnered with Weinstein to form the Third World Cinema Corporation (TWC), which sought to function as an advocacy and training program for people of colour both in front of and behind the camera, as well as a production company in its own right; Claudine was TWC’s first feature, one of only two (the other being the 1977 Richard Pryor vehicle Greased Lightning) before lack of funds scuttled the company’s ambitious plans.

What the Dassin- and Berry-directed films thus represent is not so much an expression of a newfound political consciousness as the continuity of an older one—one whose concerns and conceptions had not been rendered obsolete by the younger generation of activists gaining force in the mid-to-late ’60s, but which took advantage of the fruitful soil afforded by this freshly broken political ground. And just as both films, in the very matter of their making, help dispel the myth of a creaky Old Left clinging to an outdated, Sovietized ideology in the face of a vibrant New, so too does the multiracial makeup of their creators shake up the blindingly white cast of the conventional blacklist narrative. “The expurgation of the history of the Black Left in [the blacklist] period has led to a false vision of history in which a caricatured ‘white Left’ during the Cold War era exists entirely separate from the history of civil rights activism,” notes the International Socialist Review’s Megan Behrent in a review of Mary Helen Washington’s 2015 book The Other Blacklist, which takes Uptight’s Mayfield as one of its primary subjects. Mayfield’s biography eloquently testifies to that intertwined history, given that he had first attracted the FBI’s attention due to his friendship with the legendary actor, singer, and card-carrying Communist Paul Robeson, an elder statesman of this younger generation of Black leftists. Though Mayfield himself later disavowed the party of Stalin, he retained his internationalist revolutionary enthusiasm (visiting Castro’s Cuba in its early days) even as he became a more than committed supporter of the anti-racist cause at home: his Ghanaian exile was precipitated by his close friendship with civil rights leader Robert Williams, whose espousal of a proto-Black Panther doctrine of armed Black self-defense resulted in a Feeb-led frame-up for the 1961 “kidnapping” of a white couple who had gotten lost in Williams’ Monroe, NC neighbourhood.

There’s a risk that in sketching, even in highly imperfect thumbnail (as above), the intriguing historical, political, professional, and personal currents that flowed into these films one is potentially doing the films themselves a disservice, inadvertently suggesting (as more than a few damning-with-faint-praise reviewers did at the time) that their existence is more important than their being—that the dutiful obeisance of the studium belies the possibility of the punctum. That risk is considerably greater for Claudine, which, by both nature and design, has none of the formalist frissons of Uptight. Where the Dassin film’s thriller framework gives it license for more florid, overtly “cinematic” gestures, it wouldn’t take much to spin off Claudine into a sitcom, especially given the fact that its husband-and-wife screenwriters, Tina and Lester Pine, cut their teeth on such shows as Peter Gunn, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, and Ben Casey.

That may sound like derogation by televisual association, but it shouldn’t be taken as such. Sitcoms, after all, are founded on a formula of slight variations being played out within an essentially stable and unchanging situation of “normality”; but whereas the “normal” of most sitcoms is an affirmation of the status quo, the “normal” of Claudine is of lives whom the status quo has failed, at best, or at worst actively persecuted. (“I’m married to the Welfare Man,” says Carroll’s Claudine at one point, smiling at her own bitter humour. “And he makes me beg for them pennies, that starvation money. If I can’t feed my kids, it’s child neglect. Go out and get a little job on the side and I don’t tell him, then I’m cheatin’. If I stay at home, then I’m lazy.”) Claudine’s characters are all too aware that they have been cast in parts, that they are the inadvertent and unwilling actors of stock roles forced upon them by governments, society, and the media. “Haven’t you heard about us ignorant Black bitches, always got to be layin’ up with some dude just grindin’ out them babies for the taxpayers to take care of?” Claudine spits at Roop after he expresses incredulity at her having six kids by age 36. “I get $30 a piece for them kids. I’m living like a queen”; “Well, you know us Black studs,” Roop retorts when Claudine turns the tables, asking why he never sees his own kids. “No feelings, knock ’em up and leave ’em, don’t give a shit if the children starve.”

Words on a page are one thing; there’s nothing to say that such dialogue couldn’t come off as rather too pointed. The Pines, Claudine’s screenwriters, had previously written another film with a predominantly Black cast—A Man Called Adam (1966), starring Sammy Davis Jr. as a volatile jazz trumpeter—in which many such Harsh Truths are strangled by their angsty expression and canned drama. Rather than any deficiency of talent in the performers, this muffling has more to do with the fact that they are being voiced through the protagonist’s exalted singularity. The typical troubled genius, Davis’ trumpeter is naturally more brilliant, more perceptive, more angry, more vulnerable, more violent, more needy, more than everyone else around him; and by making him the mouthpiece for Black anger and Black injury, the film makes that anger and injury into more a personal matter than a societal one, as well as an excuse for a series of predictably histrionic confrontations. (See Sammy flip out on boorish white club patron; see Sammy flip out on sneering Black street hustlers; see Sammy flip out on bullying white cops; see Sammy flip out on Peter Lawford’s sneeringly superior white agent.)

This is one of the traps of realism, the belief that by directly invoking social ills rather than hiding behind Hollywood “fantasy,” one has freed it from our culture’s shroud of silence—that the studium itself can suffice. While Berry and the Pines do allow their actors their moments of effectively aggrieved grandstanding (e.g., Jones’ public rant at the social-assistance office about the welfare system’s catch-22 illogic), most often the characters in Claudine, freed of the burden of exceptionality, lay those ills bare through their enforced obeisance to, and cunning subversion of, the systems that govern their lives. James C. Scott proposed the concept of “hidden transcripts” to describe the ways in which oppressed populations, without deviating from the letter of the oppressor’s law, turn the very precepts of those laws against them. This is the power that the people in Claudine wield: Roop invoking his ten years of garbage-handling expertise to explain to Claudine’s wealthy white employer why he is not going to pick up a hundred-plus-pound bin; the code-switching trill Claudine puts into her voice when the woman from the welfare office comes down to surveil her apartment (and her life); and, in that final scene, an acceptance of arrest as an unspoken refusal of the refrain that is voiced throughout the film: “You can’t win.”

Where Claudine illustrates the artifice of an oppressive “real” concealing a hidden reality of resistance, Uptight’s hot-button take on contemporary Black resistance puts artifice right up front via a thoroughly unexpected animated crediting sequence courtesy of John Hubley, the left-wing animator who had gone independent in the early ’50s after his blacklisting had forced him to leave the UPA studio. (More connections: Hubley had previously done the opening titles for the Pine-written A Man Called Adam, which featured TWC’s Ossie Davis in a prominent supporting role.) From abstraction Dassin plunges us directly into reality—footage that he himself shot of the funeral parades held in Memphis and Atlanta to mark the murder of MLK—and then into a mediation of that reality, as his footage is transferred to a black-and-white television set being watched by barbershop patrons in Cleveland’s depressed, semi-industrial Hough district, where the film’s transplanted Informer plot will soon begin playing out.

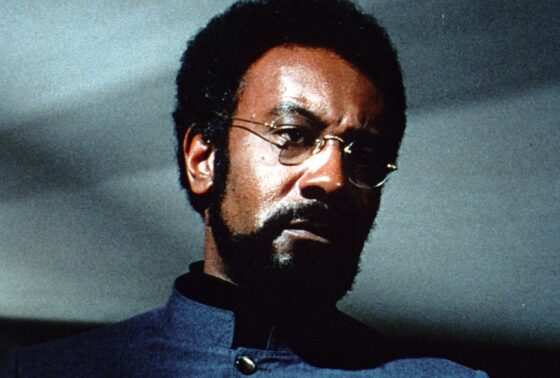

The consensus critical opinion on Uptight deemed this borrowing from O’Flaherty-via-Ford to be the film’s weakest aspect, and it’s difficult to argue otherwise. It’s not only that the Gypo Nolan surrogate, Tank Williams—a former foot soldier in the militant movement now wallowing in drink and despair, whose rebuffed attempt to rejoin his comrades leads him to turn snitch—is at best adequately performed by a sweaty, heavy-breathing Mayfield, but also that his essentially apolitical psychological-moral drama clashes with the fascinatingly political drama of his former compatriots. Although he is introduced almost immediately, sobering up under a shower (which Dassin films in strikingly intense extreme close-up, the rivulets of water seemingly threatening to dissolve Mayfield’s mountainous face), Tank is a marginal figure through the film’s first half, which is largely given over to the dispute between the advocates of Black armed struggle—represented by the cell’s hard-line leader (Raymond St. Jacques, eyes intense behind professorial spectacles and sporting a rather Soviet-style jerkin)—and those of King-style non-violent protest, embodied by a community organizer (Frank Silvera) and a white former Freedom Rider.

Though it takes place roughly 30 minutes in, the charged ideological confrontation between the cell members and the moderates (which, notably, Mayfield’s Tank is almost entirely from) is in many ways the film’s centrepiece, translating political precepts into drama without didacticism, reductive simplification, or tarnishing any position by zeroing in on the venial attributes of any one character. “There are no stars in this movement. They kill them too quick. You talk to all of us,” says St. Jacques to Silvera, and the attentive, resolute silence of the other militants during the ensuing debate (which Dassin shoots mainly in medium group shots) eloquently conveys the many voices that speak through his.

What is equally striking about this sequence is the stage upon which it is performed: a rundown bowling alley that, thanks to the production design of Alexandre Trauner (Les enfants du paradis, 1945) and the super-sharp colour cinematography of Boris Kaufman (On the Waterfront, 1954), is as plainly, gloriously artificial as an MGM musical. Dassin and company shot much of Uptight in Cleveland, but rather than aim for the street-level, location-shoot realism that had become a Hollywood standard by the late ’60s (two decades after Dassin and producer Mark Hellinger were able to present it as a revolutionary advance in The Naked City), the filmmakers place their urgently contemporary tale within an environment that, at times, resembles nothing so much as a Dantean version of Murnau’s mythical City from Sunrise (1927) (though the subterranean room where Tank is “tried” by the cell members perhaps inevitably calls to mind Lang’s M [1931]). The real locations that would normally speak to the film’s documentary veracity—the exterior of Tank’s apartment building, the neon-lit strip, the back alley where that deluge of bottles pours down, the flaming, Götterdämmerung junkyard in which Tank finally welcomes his fate—are expressionistically heightened to the extent that they suggest the paradoxical image of diorama miniatures rendered life-size. Conversely, the painstaking attention to detail in the studio-shot sequences only increases their settings’ uncanny irreality: the bowling alley, the arms depot (complete with lovingly recreated girlie pin-ups on the wall of the watchman’s office), and, à la Sunrise, an amusement park, where a drunk Tank gives a band of upscale white slummers an instructional on race relations as their bodies are contorted into comically grotesque shapes by funhouse mirrors.

This sequence especially was negatively singled out by critics at the time for its cartoonishness and on-the-nose symbolism, which, again, is a fair cop. But as part of Uptight’s constantly surprising, invigorating mixing of modes, it is, in its way, as essential to the film’s overall texture as the equally incongruous, overtly Expressionist nightmare interludes in Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945) or Powell and Pressburger’s The Small Back Room (1949), which became the signature images from those films. Further, where the Wilder and P&P sequences were bracketed off from their realist narratives proper through the vehicle of character subjectivity—both of them clearly demarcated as hallucinations being suffered by their alcoholic protagonists—the imbalance between Uptight’s political-ideological drama and its more pallid personal drama also dictates that the increasingly tanked Tank never truly becomes the dark glass through which we see the film’s made-strange world. Uptight’s is a land of imagination charged with some of the most pressing issues of its (and our) time—aesthetically, dramatically, and veristically muddled, yes, and all the more piercing for it.

Andrew Tracy