Terrible Beauty: Yonah Lewis and Calvin Thomas’ The Oxbow Cure

By Jason Anderson

Though feelings of fear and pain are palpable in almost every moment of The Oxbow Cure, a curious sense of exhilaration cuts through the frigid dead. Maybe that’s due to the co-directors’ Yonah Lewis and Calvin Thomas’ possible realization that they’ve managed to do something uncommonly brave within a Canadian system that bristles at anything resembling an authentic challenge to prevailing norms. (Another factor that stifles innovation: the traditional reliance on overstuffed scripts that have been rewritten to death in order to appease the many overlapping funding bodies—no wonder The Oxbow Cure’s quietude and stillness are such rarities.) Or maybe it’s the air of liberation that suffuses the film as it shifts from one familiar contemporary cinematic mode—that of the solo, near-silent portrait of a woman in the throes of a psychological, bodily and/or metaphysical crisis, presented with equal parts aesthetic rigour and bracing intimacy—into something altogether stranger and more confounding. For some viewers, it could also come down to a certain frisson of excitement over the possibility that Lewis and Thomas have found a fresh approach to one of the core preoccupations in Canadian arts and letters—specifically, the effects of isolation on anyone stuck somewhere in our wintry hinterlands, a time-tested trope since even before Susanna Moodie had her first dose of cabin fever. (A more recent literary analogue for The Oxbow Cure might be Margaret Atwood’s The Journals of Susanna Moodie [1970], an eerie cycle of poems written in the voice of the 19th-century author of Can-lit perennial Roughing It in the Bush.)

Whichever interpretive framework one applies, The Oxbow Cure has no lack of boldness. For this and several other reasons, it marks a great leap in sophistication from Amy George (2011), the duo’s micro-budget debut about an adolescent Toronto east-ender who seeks to learn the ways of women so as to further his chances of becoming a great artist. One of that film’s virtues was the directors’ ease with a largely non-professional or first-time cast, and The Oxbow Cure sees the pair continue their collaboration with Claudia Dey, better known as the author of much-decorated plays such as Trout Stanley and The Gwendolyn Poems. While Dey was charming as the understandably perplexed mother of Amy George’s adolescent hero, here she faces far greater demands, seeing as she essentially qualifies as The Oxbow Cure’s only performer (or at least the only human one).

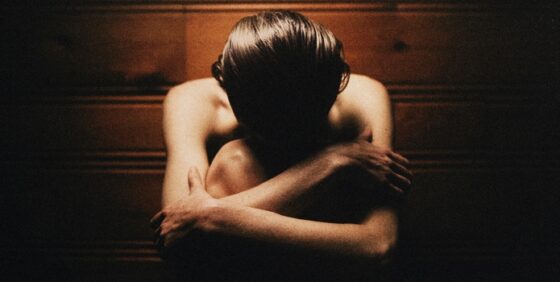

Dey gives a dauntingly intense turn as Lena, a woman whom we first see preparing for a sojourn to her family’s cottage in the depths of winter. Her anxiety is signalled at a going-away party, the worry being evident in her eyes whenever she has a moment away from her visitors. Details are scant, but a few facts about Lena’s life emerge—most notably her grief over the recent death of her father (seen briefly in a hospital room and heard in a voicemail message), and the apparently constant pain she suffers due to a disease that affects her spine. A regimen of yoga exercises and sauna time appears to offer the only respite from her suffering as she maintains a lonely vigil by a frozen lake. Escaping the confines of the cottage and her steadfastly maintained indoor routines (which also include cooking and an online chat with a fellow sufferer), she ventures out in the daylight hours to walk across the lake and into the surrounding woods. The film’s meticulously composed sound design emphasizes the rasp of her breath and the crunching of her footsteps, fostering the same discomfiting degree of proximity evoked by the many close-ups of Dey’s long bare limbs and spine as she stretches. Lena could clearly use some company, but even the dog that she rescues from a state of neglect at a nearby cottage doesn’t stick around for long once she brings him home. But as Glenn Gould demonstrated in his Solitude trilogy of radio documentaries on life in some of the country’s most remote communities, lonely rarely stays lonely for long in places like this. The film’s sound world is highly suggestive of the cracks forming in Lena’s constricted existence, as the Bergman-esque mood of icy gloom is periodically shattered by jarring snatches of music on the soundtrack, which include two rapturously overblown mid-’60s ballads by P.J. Proby (Scott Walker would have been too on the nose, I suspect) and several brassy interludes composed by Yonah’s brother Lev.

And then it gets weird. Really weird. That said, The Oxbow Cure’s departure into the realms of the supernatural would seem par for the course if we were deep inside of one of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Thai jungles rather than a snowbound corner of Ontario. Even those viewers who resist this change of tack—which is presaged at earlier stages of the proceedings with considerable care—should recognize how much the climactic scenes of The Oxbow Cure are consistent with the film’s earlier emphasis on physicality and its overall drive to convey Lena’s internal struggles without the crutch of language. And while Lewis and Thomas’ ambitions may exceed their means at times, the best of the duo’s efforts have the force and strangeness of myth. From these wintry depths, a terrible beauty is born—you’d best make a fire to keep it from freezing over again.

The Oxbow Cure opens at TIFF Bell Lightbox on August 23.

Jason Anderson